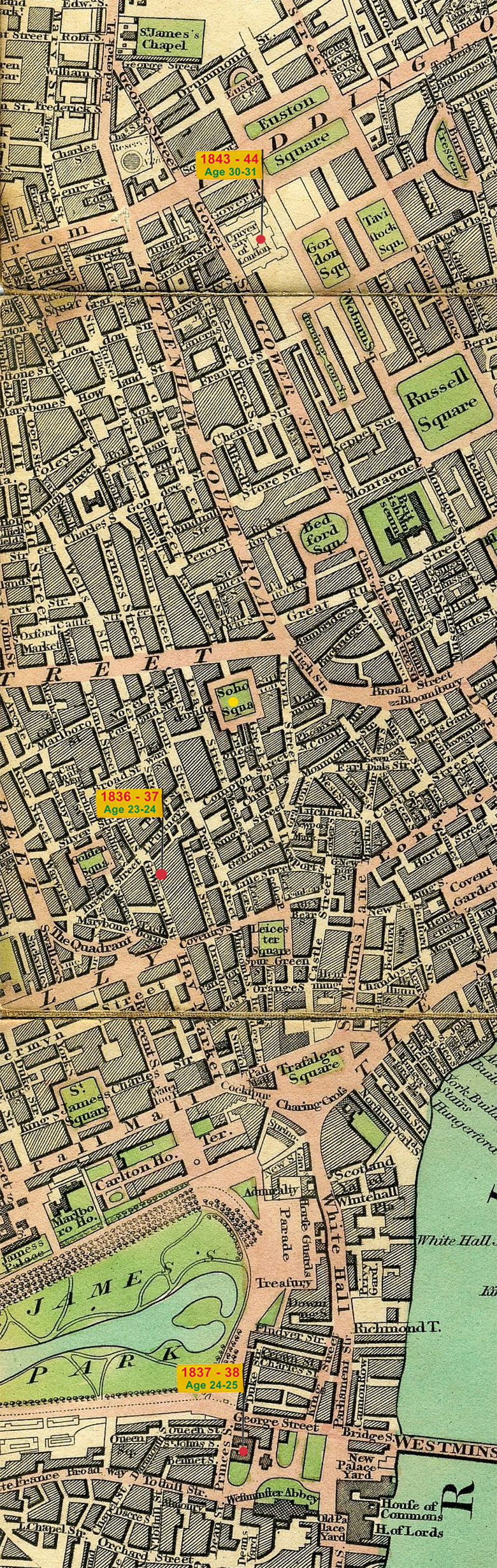

After serving in three apprenticeships and taking early medical cousework in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, John Snow travelled to London for further medical education.

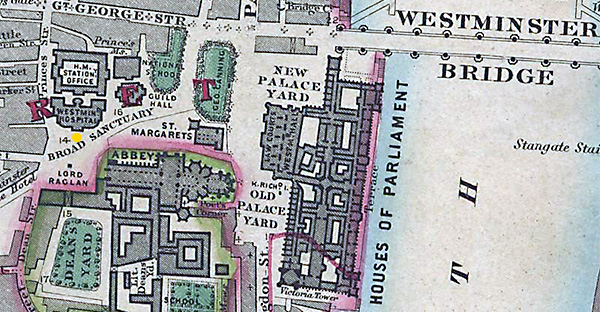

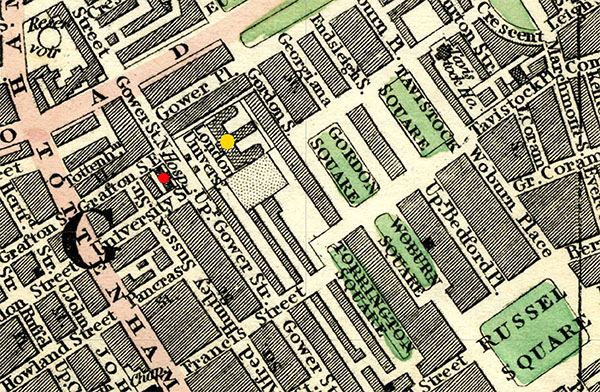

As seen at right in an elongated section of Mogg's 1834 map, his first year (1836-37) was spent at the Huntarian School of Medicine on Great Windmill Street near his home at 11 Bateman’s Buildings by Soho Square (gold dot).

Thereafter, he travelled south to the Westminster Hospital by Westminster Abbey for further clinical training (1837-38), and then back north to the University of London on Gower Street (1843-44) where he received both his Bachelor of Medicine (M.B.) and Doctorate of Medicine (M.D.) degrees.

By the time he was through with his 17 years of apprenticeships and in-school medical or hospital education, he was 31 years old.

Since death came early at age 45, the applied phase of his life following his education had to open many doors during a short span of 14 years. Yet excel he did, eventually becoming a historical icon in both epidemiology and anesthesiology, and well known in the field of cartography.

The Beginning

His introduction to the larger medical community of London occurred on November 10, 1838 when his first publication (i.e., a letter to the editor) appeared in The Lancet, the basis stemming from an observation he made during his second year as an assistant at the Hunterian School of Medicine (see publication #1. at Stream1_introduction_d).

In London there were 21 medical schools that offered education to qualify as a general practitioner, at that time the lowest but most common rank in the medical profession. Requirements were set by the Royal College of Surgeons and the Society of Apothecaries charged by law to examine and license those who wanted to become general practitioners. The Lancet published lists each year of the courses being offered by the medical schools to address these requirements. Some schools provided just courses, others had courses and links to specific hospitals, and still others, based in hospitals, offered both courses and clinical experience. Among the lowest-priced institutions was the Hunterian School of Medicine (also known as the Hunterian Anatomy School, Great Windmill Street), offering a full range of lectures and anatomy courses, and had over the years an excellent reputation. Snow enrolled in October 1836 for one year of classes, but remained for another year to increase his expertise in anatomy. To this end, he became a part-time assistant to his anatomy professor in October 1837, preparing specimens for the students.

A chemistry lecturer at the school had read an article promoting the injection of a solution of arsenic of potash into blood vessels of cadavers so as to highlight them. The intent was to make the vessels easier for students to identify. Snow agreed, adopted the procedure and had much initial success.

But then, some of the students started to become ill with cramps and vomitting. Snow hypothesized that arsenic of potash was a potential problem and decided to do some experimentation. He vaporized the cadaver tissue containing arsenic of potash, and managed to procure a small amount of metalic arsenic, known to cause acute symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and severe diarrhea.

Forthwith, he informed the faculty that this mode of injection for highlighting blood vessels was dangerous. The procedure was immediately stopped.

For further details on the Hunterian Medical School, go to the appropriate section in Stream 2_BSPoutbreak_b.

For further details on the Westminster Hospital, go to the appropriate section, also in Stream 2_BSPoutbreak_b.

These same characteristic of:

would become typical of John Snow's future modus operandi.

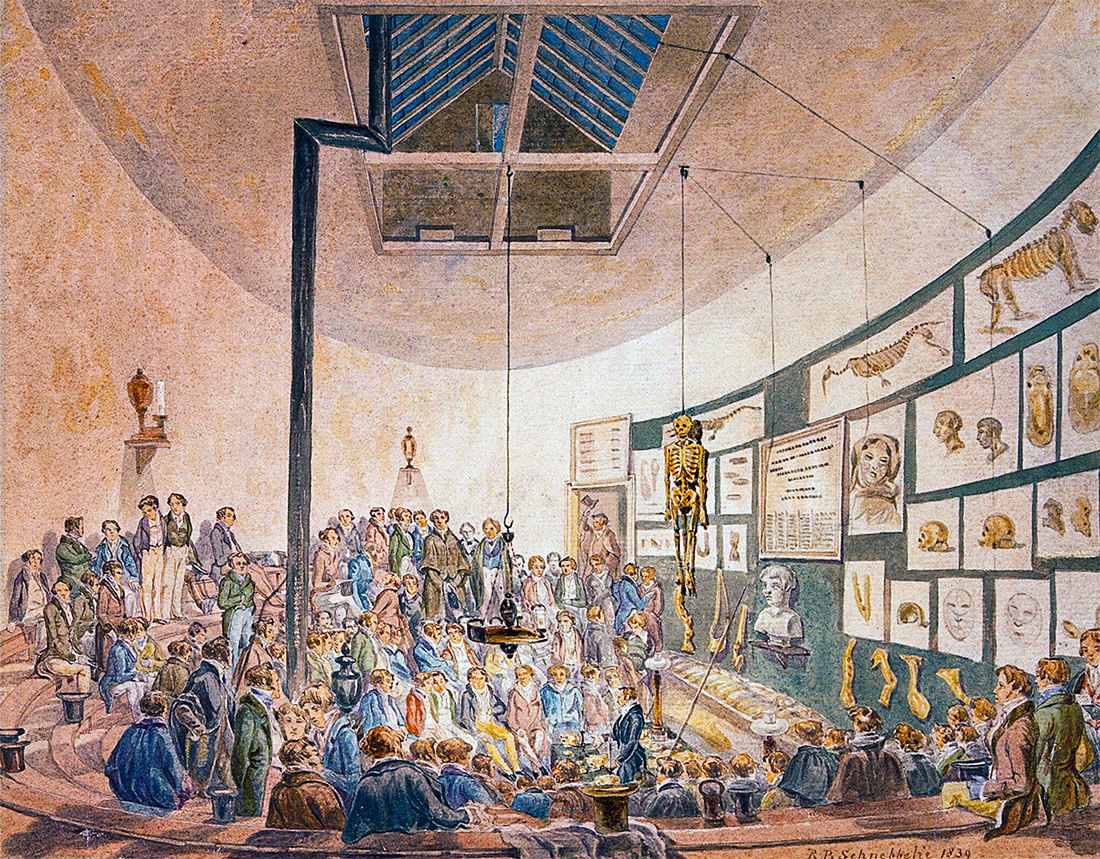

LECTURE HALL AND STUDENTS AT HUNTERIAN MEDICAL SCHOOL

The Hunterian School of Medicine closed in 1838, following Snow's year as an assistant. Yet the London anatomy theater remained open, rented by surgeon and anatomy specialist John Gregory Smith until 1842.

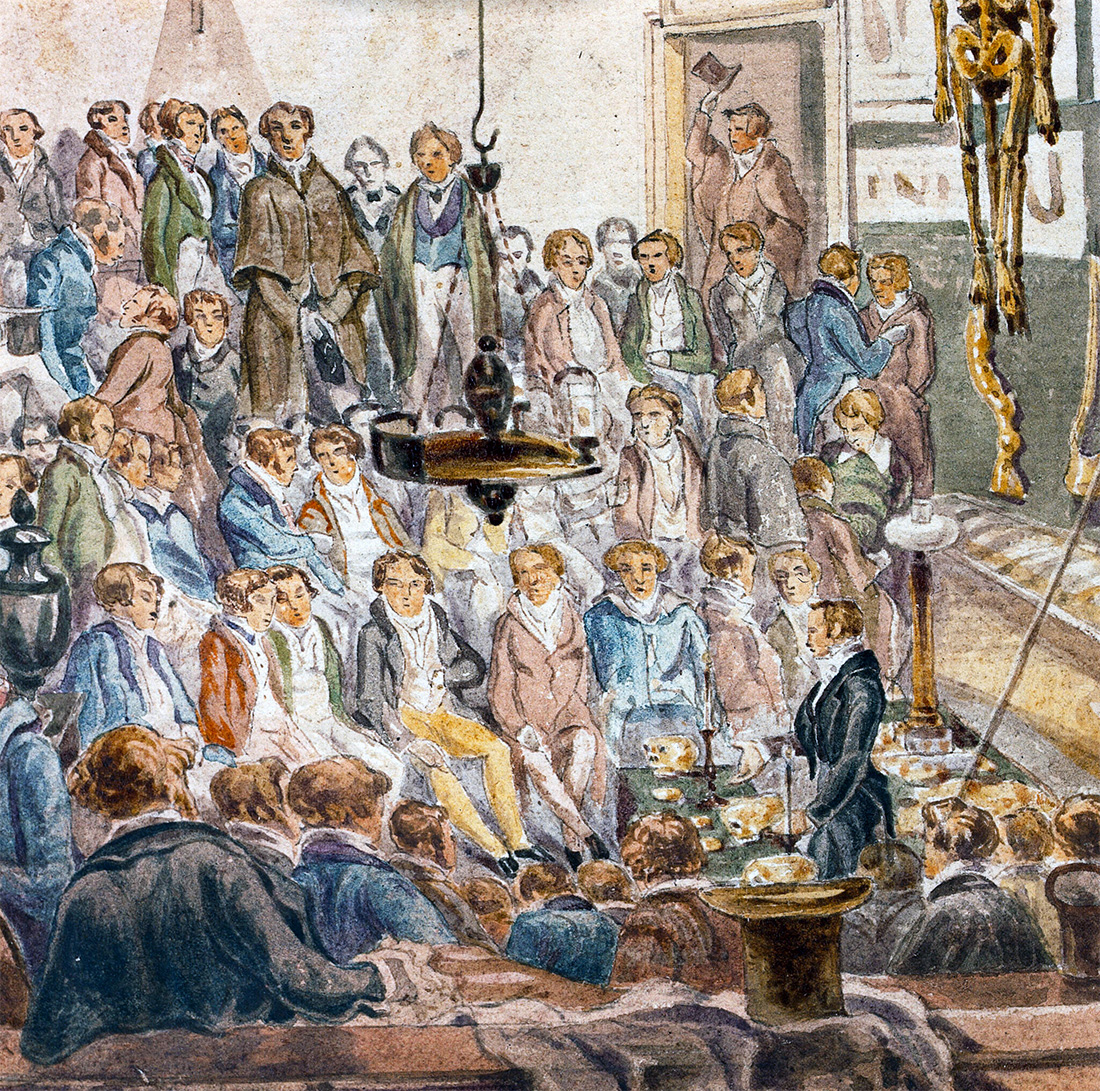

Shown below is a drawing of the lecture theater based on a sketch made in 1839 by architectural illustrator Robert Bremmel Schnebbelie, followed by a second close up of the attendees. It appears to be a cool day in London with many wearing formal tailcoats, leaving their beaver skin or silk top-hats on the benches. The lecture hall is heated by a stove in the center, with a black stove pipe rising to the ceiling. Standing towards the front before a skelton, various bones and wall illustrations is John Gregory Smith in a black tailcoat and white shirt.

ENLARGED VIEW OF STUDENTS AND LECTURER

Source of both drawings: Wellcome Collection. A lecture at the Hunterian anatomy school, Great Windmill Street, London. Watercolour by R.B. Schnebbelie, 1839.

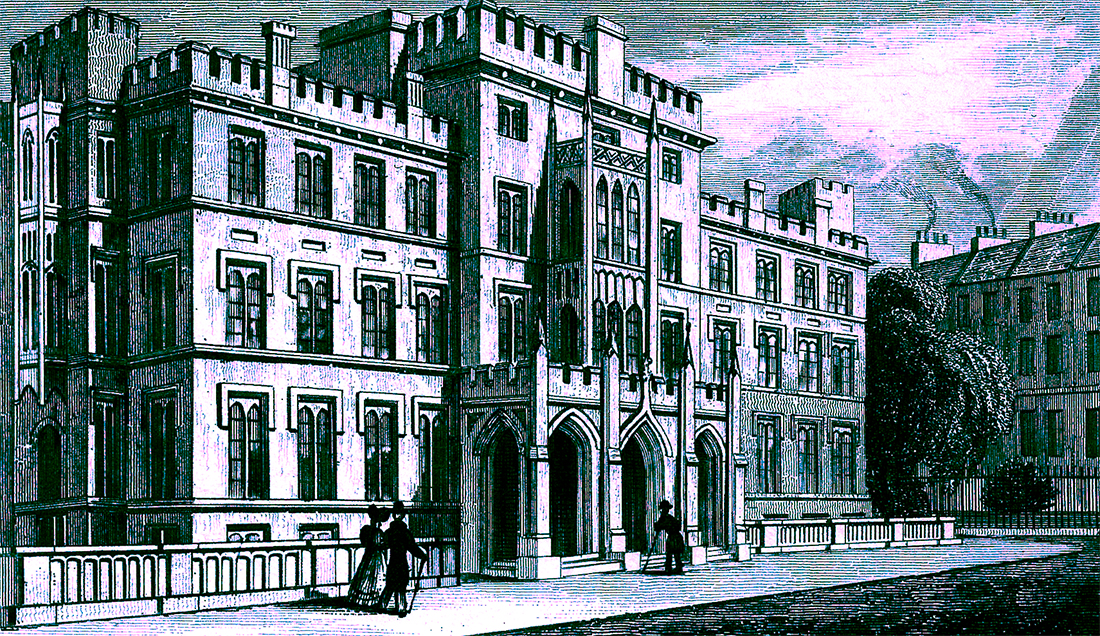

While working part-time in 1837 with his anatomy teachers at the Hunterian School of Medicine, John Snow expanded his education by studying clinical subjects during 1837 and 1838 at the Westminster Hospital (see Moggs's 1834 map above and images below). Snow was 24 years old when he started this phase of his medical studies.

New Westminster Hospital, 1834

Westminster Hospital and Westminster Abbey, 1842

History from Infirmary to Hospital

The Westminster Hospital has a long and famous history. It was started in 1719 as an infirmary for sick poor people and had about 18 beds. A few years later in 1721,it was replaced by a second infirmary, but this time with 31 beds. Subsequently, this too was replaced with a third infirmary, which lasted from 1735 to 1834. Along the way, the infirmary in 1760 was renamed Westminster Hospital and grew to 98 beds.

In 1827 a new surgeon named George James Guthrie came to Westminster Hospital (at right). He had been the foremost military surgeon of his day and was a man of strong opinions.

Two factions quickly developed in the hospital, with one siding with Guthrie and the other with his opponents. An argument during Guthrie's first year at the hospital included insulting remarks, which lead to a duel between Guthrie's pupil, Hale Thompson, and a member of the opposing group.

The two men fired three shots at each other but no hits were scored. Someone suggested as surgeons that perhaps they would have been more deadly with scalpels rather than with pistols. Subsequently, Hale Thompson was cited in The Lancet as "bullet-proof Thompson."

John Snow at the time was only 14 years old, but may have heard of the duel.

Pistol dueling was not uncommon during these times in London, typified by illustrator Robert Cruikshank, older brother of well-known George Cruikshank, in a 1825 drawing of two men dueling "over an argument of a love affair."

New Building of 1834

After Guthrie was at Westminster for a few years, a building fund was started with plans to create a new hospital. The site was identified on Broad Sanctuary across the street from the Westminster Abbey and a block or two East of the Houses of Parliament and the Thames river. The building was completed in November, 1834. Stanford's map of 1862 shows the exact location (see gold dot).

Including the site and new building, the hospital was quite costly. At the time, it was considered to be state-of-the art, with each ward having its own bath room. The new building was there to greet John Snow in 1837 when he started his clinical training at age 24. It remained in use as a hospital until 1939, or 81 years after Snow's death.

When the new Westminster Hospital opened in 1834, Guthrie proposed that a school of medicine be started in connection with the hospital. This was violently opposed by his colleagues, but fortunately no one suggested another duel. Soon thereafter the private Westminster School of Medicine was started, and in 1841 was incorporated as an official medical school attached to the hospital.

By 1841, John Snow had already completed his two years of clinical training (1837-38) and passed his licensing exams to administer and sell therapeutic drugs and practice medicine. Thus, while attending clincial rounds at the Westminster Hospital, he never formally enrolled in the Westminster School of Medicine. Nevertheless, he was viewed by many as a "Westminster man" and latter praised for having put anesthesia on a sound scientific basis and for his studies of the epidemiology of cholera.

A Several Year Setback

In May 1839, Snow received a public rebuke from the Editor of the The Lancet, addressing his early publications with a comment about his "criticising the productions of others" (see publication section Irritation with Snow between #4 and #5 at Stream1_introduction_d). At about the same time, he applied for the recently vacated position of Apothecary at the Westminster Hospital, and for some unstated reason, was passed over.

Having settled in his new home at 54 Frith Street in 1838 and finding the area to his liking, Snow decided to become a general practitioner tending to his neighborhood patients, while active since October 1837 as a full member in the Westminster Medical Society.

Yet personal ambition took over. With passing years, Snow gave thought to additional education, specifically earning his Doctorate of Medicine, conferring the terminal M.D. degree. This journey took him to the University of London.

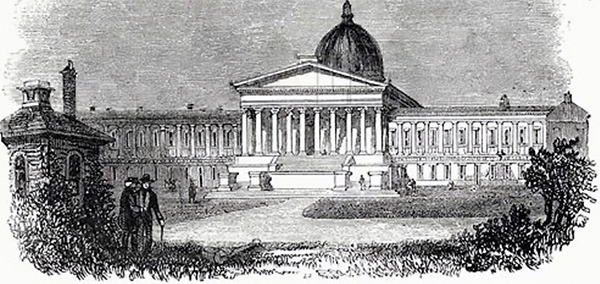

The University of London was located on upper Gower Street, to the north of the Soho region where John Snow worked and lived. As shown to the right in Crutchley's map of 1846, the medical school was on the east side of Gower Street (gold dot) while the North London Hospital (soon to be changed to the University College Hospital), was on the west side of the street (red dot).

The University of London is also seen above in the elongated section of Mogg's 1834 map, by the flag "1843-44, Age 30-31)."

Restrictive Universities and Medical Licensure

Noted previously, in England during the mid-1800s, only a few institutions were empowered to grant licenses to practice medicine. A person could either go to the universities of Oxford or Cambridge, or apprentice with an established person who was licensed as a medical practitioner. Both Oxford and Cambridge were restricted to members of the Church of England (the Snow family were members) but were far too expensive for the laboring class. As a result of economic restrictions, Snow decided to follow the second route, and gain his full medical approval through licensing. Now years later in 1843-44, he chose to sit for the examinations at the newly created University of London to obtain his formal medical degrees.

HISTORY OF UNIVERSITY OF LONDON

The Radical University

1825. (Snow was aged 12 and still in York). Thomas Campbell (1777-1844), the Scottish poet, wrote an open letter in the Times of London to Henry Brougham, a member of Parliament, calling for the establishment of a university in London. Brougham (at right) became the driving force behind a campaign which was actively supported by those excluded from university education - Catholics, Jews and non-conformists.

1826. (Snow was aged 13 and still in York). The University of London was formally founded on the 11th of February. A fundamental principle was that not only would students of all beliefs be allowed entry, but that no religious subjects would be taught. The established interests of the Church of England prevented the University of London from receiving a royal charter, so it was set up as a joint stock company. The new University was vilified by the Church of England as The Godless Institution of Gower Street, and by the Tory conservative political party as The Cockney College, because of its aim to extend access to university education from the very rich to the growing new middle class.

1828. (Snow was aged 15 and in his apprenticeship in Newcastle-upon-Tyne). The first academic sessions of the University started in October, including the study of law. Chairs were established in several subjects which had not previously been taught in English universities, for instance modern foreign languages and English language and literature.

1834. (Snow was aged 21 and in his apprenticeship in Pateley Bridge). The North London Hospital (below) was opened opposite the University of London.

Degrees in Medicine

1836. (Snow was aged 23 and attending the nearby Hunterian School of Medicine). The University was renamed University College, London and received its Royal Charter on the 28th of November. On the same day, a new University of London was established with the power to award degrees in Medicine, Arts and Laws.

1837. (Snow was aged 24 and doing his ward rounds at Westminster Hospital). The North London Hospital became University College Hospital.

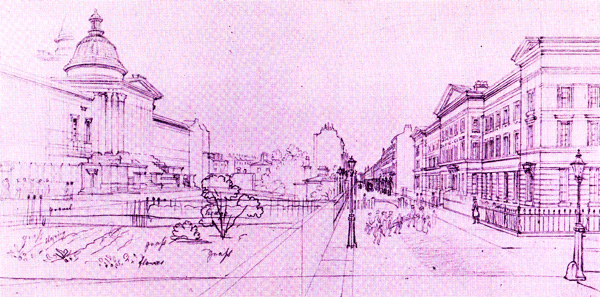

In an 1840 sketch at right, University College, London is seen on the left and University College Hospital, across Gower Street, is shown on the right.

In the next few years, Snow decided that the formal degrees of M.B. (Bachelor of Medicine) and M.D. (Doctorate of Medicine) were essential if he was to rise as far as his abilities would take him. He assembled his dossier showing his years of apprenticeship, one year of courses in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, the full curriculum at Hunterian School of Medicine, and other experiences, as described in the University of London's medical prerequisites.

1843. John Snow at age 30 was examined on November 23, 1843, and received his Bachelor of Medicine (M.B.) degree from the University of London in the second highest group (i.e., second division).

1844. John Snow completed his doctoral examination on December 20, 1844, and received his Doctorate of Medicine (M.D.)

degree from the University of London. This time he scored in the highest group (i.e., the first division). Snow was 31 years old and had now completed the many years of his formal medical education.

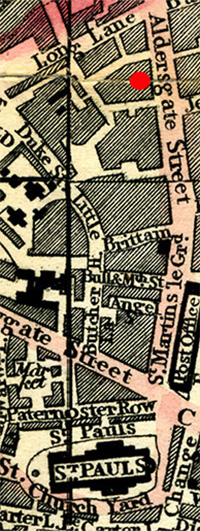

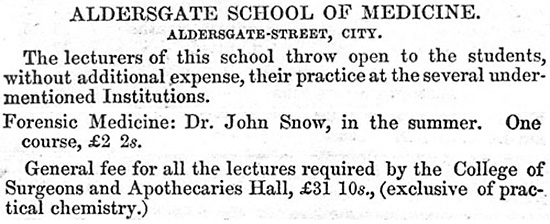

1846. At age 33 when busy establishing his career, Snow becoming a lecturer of Forensic Medicine at the Aldersgate School of Medicine, north of St. Paul's Cathedral on Aldersgate Street (see red dot in 1846 map). He remained there for three years until the school closed due to lack of funding.

At the same time in 1846 he commissioned a portrait by Thomas Jones Barker, shown partially here. The painting represented the dividing point between his extensive education and his professional working life.

As was their usual policy, The Lancet in 1846 published the course offerings of the various medical schools in London. What follows is the section of The Lancet, volume 2, page 345 that mentions lecturer John Snow for the coming 1847 summer session at Aldersgate School of Medicine.

John Snow learned of the school from a friend at the Westminster Medical Society, who had joined the faculty in 1844. Two years later a position opened at Aldersgate as lecturer in forensic medicine. Because of his M.D. degree and publication on lead poisoning of a five-year-old boy (see publication #11. at Stream1_introduction_d), the institution felt that Dr. Snow was qualified to teach the course, and he was hired in 1846 as lecturer.

Unfortunately, the Aldersgate School of Medicine was not able to compete with the reputation of nearby St. Bartholomew's Hospital School of Medicine, and it was forced by lack of funds to close in 1849. His friend who initially told him of the Aldersgate position went on to University College Hospital, but John Snow did not follow him, and in fact never sought another academic post. Instead he became busy with a successful medical practice and research in anesthesiology and in the epidemiology of cholera.

During his prior time at the University of London, John Snow had become increasingly interested in anesthetics and decided to specialize in that subject. In the next few years, he conducted numerous experiments using ether, both on animals and himself.

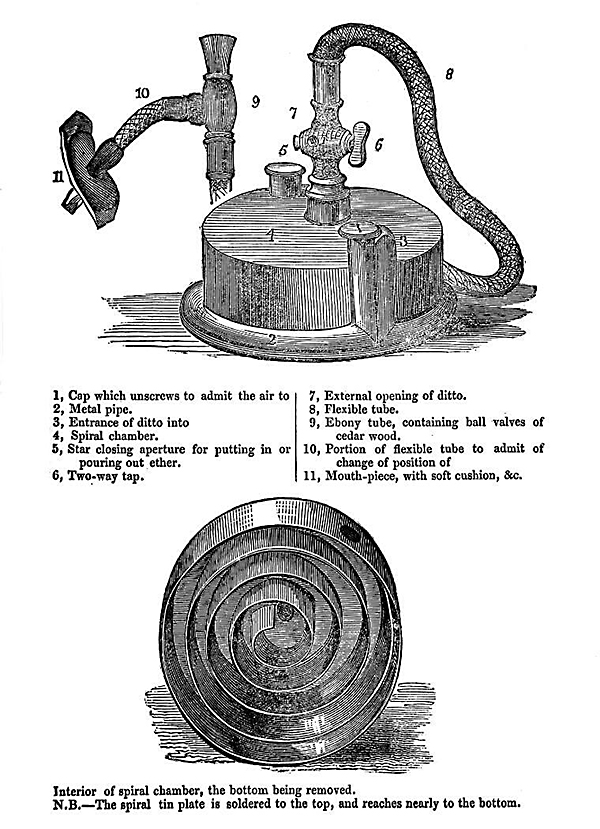

An improved ether inhaler was one of his inventions (at right), described in 1847 (for further details, see publication #21-22 at Stream1_introduction_d).

Air and ether were mixed as vapor at one side of the apparatus and drawn over and round the spiral chamber, to be inhaled by the patient through a mouth-tube fitted with cedarwood ball valves.

His work attracted the attention of Robert Liston (1754-1847), then at University College Hospital and the foremost surgeon in the city. Liston (shown at left) was impressed with the difference between the result of anesthesia as administered by Snow, versus that of less cautious anesthesiologists.

In the years following Snow's graduation from the University of London, the elder Liston become a patron of young John Snow, and soon Snow was recognized as the premier anesthetist in London, with a steady income to support his other interests.

Snow published eight articles in 1847 on the results of his experience with ether, including the definition of four anesthesia stages which continue to be recognized in modern times.