How did the son of a laborer from York end up as a physician in London among the most prominent members of British society, and be asked to administer chloroform on two occasions to Queen Victoria? The answer appears here.

REMARKABLE JOURNEY

Following his working-class start in life, John Snow toiled long and hard to become a physician. Early during his illustrious career he developed a lasting interest in anesthetic agents. Shortly after anesthetic ether was introduced in Great Britain, Snow in 1847 published an article entitled, On the Inhalation of the Vapor of Ether (#21-22). He was then 34 years old and only three years beyond his M.D. degree. Thereafter and for many years to come, he produced a series of papers on his clinical experience with anesthesia.

Besides ether as an anesthetic agent, he also focused on chloroform. It was not until shortly after his death in 1858, however, that Snow's major work appeared: On Chloroform and Other Anesthetics, and Their Action and Administration, with final editing by his close friend, Benjamin Ward Richardson.

BIRTHS AND ANESTHESIA

During his career, Snow anesthetized 77 obstetric patients with chloroform. Typically he would delayed initiating the anesthetic until patients approached the second stage of labor. He limited the dose so that his patients would achieve satisfactory analgesia, but not be rendered completely unconscious. Many pushed on command during the delivery. Snow felt that light levels of anesthesia had little effect on labor and had even observed instances in which labor appeared to accelerate after he began anesthetic induction. While Snow believed it possible for the obstetrician to administer the anesthetic, he suggested that it would be safer if anesthesiology was delegated to some other person.

During the middle of his career, Snow began working with three of Queen Victoria's physicians, including Dr. Charles Locock. All had reservations about the use of anesthesia, as did most physicians of the day.

Prince Albert and Queen Victoria were marrried in 1840 and had their first of nine children in 1841 (see images, 1841, both age 22).

Starting in 1848 with the upcoming birth of Princess Louise, Prince Albert discussed the potential use of anesthesia with Queen Victoria's doctors, who after conferring with Dr. John Snow, the Queen's physicians were not supportive.

The matter came up again in 1850 during the Queen's pregnancy with Prince Arthur, but this time Prince Albert consulted directly with Dr. Snow. Neither were able to convince Royal Physician Sir James Clark.

Finally in 1853, with gradual acceptance of chloroform, Royal Physician Clark called upon Snow to administer chloroform in 1853 to the Queen during the birth of Prince Leopold (blue dot), and four years later to Princess Beatrice in 1857 (pink dot) , seen below in a family portrait by Leonida Caldesi and Mattia Montecchi, the Italian-born partners known for their formal photographs of the British royal family.

In keeping with most families of her time, Victoria and Albert over the first 17 years of their marriage had many children, nine in all. Most of her children married into other royal families of Europe:

• Victoria Princess Royal, (born 1840, married Friedrich III, German Emperor);

• Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, (born 1841, married Alexandra, daughter of Christian IX of Denmark);

• Alice, Princess, (born 1843, married Ludwig IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine);

• Alfred, Prince and Duke of Edinburgh and of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (born 1844, married Marie of Russia);

• Helena, Princess (born 1846, married Christian of Schleswig-Holstein);

• Louise, Princess and Dutchess of Argyll, (born 1848, married John Campbell, 9th Duke of Argyll);

• Arthur, Prince and Duke of Connaught, (born 1850, married Louise Margaret of Prussia);

• Leopold, Prince  and Duke of Albany, (born 1853, married Helen of Waldeck-Pyrmont); and

and Duke of Albany, (born 1853, married Helen of Waldeck-Pyrmont); and

• Beatrice, Princess  (born 1857, married Henry of Battenberg).

(born 1857, married Henry of Battenberg).

Royal Family, 1857

While the Queen and Prince Albert first showed early interest in chloroform, no anesthetic was administered for her seventh delivery of Arthur in 1850, the future Duke of Connaught. Such reservations disappeared in 1853 by the time her eighth delivery occurred (Prince Leopold). Dr. John Snow gave Queen Victoria chloroform, but used a drop method on a handkerchief (at left) rather than the inhaler he had earlier invented.

The social elite in London soon followed the Queen's lead, adding further credibility to the use of anesthesia. In 1857, the Queen had Princess Beatrice, her ninth and final child, also with Dr. John Snow providing chloroform. He again used the open-drop approach, likely at her or Dr. Locock's request.

Following the 1853 birth of Leopold, the Queen wrote in her diary that the choloform administered by handkerchief during the birth by John Snow was "soothing, quieting and delightful beyond measure." Another accolade after her ninth and last delivery of Princess Beatice appeared in her personal journal and in letters, referring to it as "blessed chloroform." Her positive experience with chloroform was widely known in London, adding to the enhanced reputation as an anesthetist of Snow from 1853 until his death in 1858.

Snow's friend and biographer, Sir Benjamin Richardson featured in Stream 1 e: Memoir of his friend Benjamin Ward Richardson, wrote several paragraphs on the impact of Snow's experience with Queen Victoria. The first two paragraphs were more technical in nature, as when one clinician describes something to another, while the third paragraph had a jocular quality, that spoke of Snow's personality and bedside manner.

"By his earnest labors Dr. Snow soon acquired a professional reputation, in relation to his knowledge of the action of anesthetics, which spread far and wide, and the people, through the profession, looked up to him from all ranks, as the guide to whom to entrust themselves in "Lethe's walk" [a colloquial expression -- moving on from painful or unpleasant matters]. On April 7th, 1853, he administered chloroform to Her Majesty at the birth of the Prince Leopold. A note in his diary records the event."

"The inhalation lasted fifty-three minutes. The chloroform was given on a handkerchief, in fifteen, minim doses; and the Queen expressed herself as greatly relieved by the administration. He had previously been consulted on the occasion of the birth of Prince Arthur, in 1850, but had not been called in to render his services. Previous to the birth of Prince Leopold he had been honored with an interview with His Royal Highness the Prince Albert, and returned much pleased with the Prince's kindness and great intelligence on the scientific points which had formed the subject of their conversation. On April 14th, 1857, another note in the diary records the fact of the second administration of chloroform to Her Majesty, at the birth of the Princess Beatrice. The chloroform again exerted its beneficent influence, and the Queen once more expressed her satisfaction."

"Inquisitive folk often overburdened Snow, after these events, with a multitude of questions of an unmeaning kind. He answered them all with good-natured reserve. 'Her Majesty is a model patient,' was his usual reply: a reply which, he once told me, seemed to answer every purpose, and was very true. One lady of an inquiring mind, to whom he was administering chloroform, got very loquacious during the period of excitement, and declared she would inhale no more of the vapor unless she were told what the Queen said, word for word, when she was taking it. 'Her Majesty,' replied the dry doctor, 'asked no questions until she had breathed very much longer than you have; and if you will only go on in loyal imitation, I will tell you everything.' The patient could not but follow the example held out to her. In a few seconds she forgot all about Queen, Lords, and Commons; and when the time came for a renewal of hostilities, found that her clever witness had gone home, leaving her with the thirst for knowledge still on her tongue."

JOHN SNOW'S CASE RECORDS

The case records of the Queen Victoria's eighth and ninth births are presented next.

BIRTH OF PRINCE LEOPOLD AT BUCKINGHAM PALACE

Main Points

• Chloroform was administered to Queen Victoria for the birth of Leopold on Thursday, April 7, 1853.

• Never before was chloroform used during childbirth for a reigning monarch.

• The Queen had experienced slight pains over the past four days.

• At 12:20 PM, Snow poured 18 drops (or 15 minims) of chloroform onto a folded handkerchief.

• The chloroform was inhaled for 53 minutes with the handkerchief held over the Queen's nose and mouth.

• The Queen noted that pain was trifling during uterine contractions and completely absent between contractions.

• The Queen never entirely lost consciousness.

• The placenta was expelled in a very few minutes.

• Afterwards, the Queen appeared very cheerful and satisfied with the effect of chloroform.

The Case Report

Administered Chloroform to the Queen in her confinement. Slight pains had experienced since Sunday. Dr. Locock was sent for about nine o'clock this morning, stronger pains having commenced, and he found the os uteri had commenced to dilate very little. I received a note from Sir James Clark a little after ten asking me to go the Palace. I remained in an apartment near that of the Queen, along with Sir J. Clark Ferguson and (for the most part of the time) Dr. Locock till a little a twelve.[1] At twenty minutes past twelve by a clock in the Queen's apartment I commenced to give a little chloroform with each pain, by pouring about 15 minims by measure on a folded handkerchief. The first stage of labor was nearly over when the chloroform commenced. Her Majesty expressed great relief from the application, the pains being trifling during the uterine contractions, and whilst between the periods of contraction there was complete ease. The effect of the chloroform was not at any time carried to the extent of quite removing consciousness. Dr. Locock thought that the chloroform prolonged intervals between the pains, and retarded the labor somewhat. The infant was born at 13 minutes past one by the clock in the room (which was 3 minutes before the right time); consequently the chloroform was inhaled for 53 minutes. The placenta was expelled in a very few minutes, and the Queen appeared very cheerful and well, expressing herself much gratified with the effect of the chloroform.

[1] Snow, it would seem, took especial care when writing here of his part in the Queen's confinement. His handwriting is better than in the immediate preceding entries, and he probably changed the nib of his simple pen to ensure even more clarity. However, he made a slip of pen. Almost certainly he meant to write till a little after twelve.

Source: Ellis, Richard H. (ed): The Case Books of Dr. John Snow, Medical History, Supplement No. 14, Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, London 1994, p. 271.

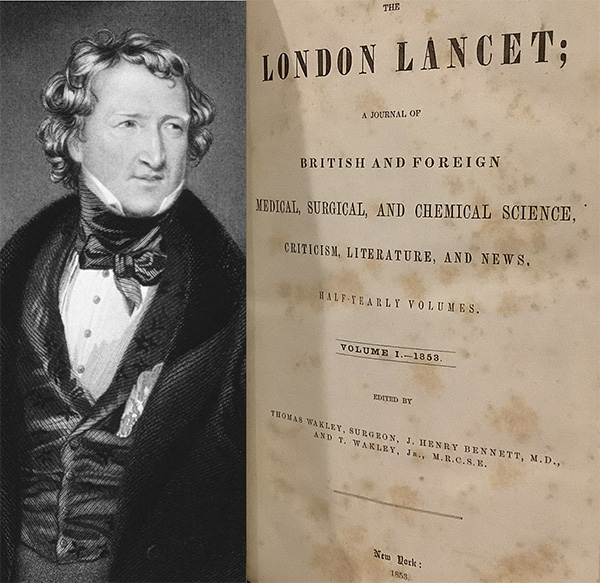

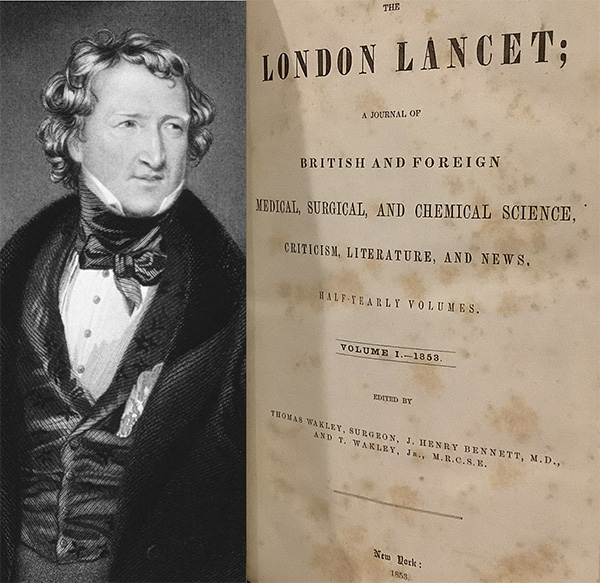

CRITICAL REACTION OF THE LANCET, BIRTH OF LEOPOLD

After learning of the April 7, 1853 use of chloroform by Queen Victoria at the birth of Prince Leopold, Editor Thomas Wakely of The Lancet in an editorial challenged the accuracy of the information, and then condemned the Queen's physicians and Dr. John Snow (although not by name) for even considering anesthesia. Queen Victoria ignored this admonition and received chloroform again four years later at the birth of Beatrice, her ninth and final child.

Thomas Wakely and Critical Editorial

The Lancet, May 14, 1853.

A very extraordinary report has obtained general circulation connected with the recent accouchement of her most gracious Majesty Queen Victoria.  It has always

been understood by the profession that the births of the Royal children in all instances have been unattended by any peculiar or untoward circumstances. Intense astonishment, therefore, has

been excited throughout the profession by the rumor that her Majesty during her last labor was placed under the influence of chloroform, an agent which has unquestionably

caused instantaneous death in a considerable number of cases. Doubts on this subject cannot exist. In several of the fatal examples persons in their usual health expired while the process of inhalation was proceeding, and the deplorable catastrophes were clearly and indisputably referable to the poisonous action of chloroform, and to that cause alone.

It has always

been understood by the profession that the births of the Royal children in all instances have been unattended by any peculiar or untoward circumstances. Intense astonishment, therefore, has

been excited throughout the profession by the rumor that her Majesty during her last labor was placed under the influence of chloroform, an agent which has unquestionably

caused instantaneous death in a considerable number of cases. Doubts on this subject cannot exist. In several of the fatal examples persons in their usual health expired while the process of inhalation was proceeding, and the deplorable catastrophes were clearly and indisputably referable to the poisonous action of chloroform, and to that cause alone.

These facts being perfectly well known to tile medical world, we could not imagine that any one had incurred the awful responsibility of advising tile administration of chloroform to her Majesty during a perfectly natural labor with a seventh child [actually the eighth of her nine children]. On inquiry, therefore, we were not at all surprised to learn that in her late confinement the Queen was not rendered insensible by chloroform or by any other anesthetic agent. We state this with feelings of the highest satisfaction. In no case could it be justifiable to administer chloroform in perfectly ordinary labor; but the responsibility of advocating such a proceeding in the case of the Sovereign of these realms would, indeed, be tremendous. Probably some officious meddlers about the Court so far overruled her Majesty's responsible professional advisers as to lead to the pretence of administering chloroform, but we believe the obstetric physicians to whose ability the safety of our illustrious Queen is confided do not sanction the use of chloroform in natural labor. Let it not be supposed that we would undervalue the immense importance of chloroform in surgical operations. We know that an incalculable amount of agony is averted by its employment. On thousands of occasions it has been given without injury, but inasmuch as it has destroyed life in a considerable number of instances, its unnecessary inhalation involves, in our opinion, an amount of responsibility which words cannot adequately describe.

We have felt irresistibly impelled to make the foregoing observations, fearing the consequences of allowing such a rumor respecting a dangerous practice in one of our national palaces to pass unrefuted. Royal examples are followed with extraordinary readiness by a certain class of society in this country.

Four years later in 1857 at the birth of her last child, Queen Victoria again used chloroform. The Lancet continued over the ensuing years to criticize Dr. Snow for his innovative ways, but more because he favored the germ theory over the later-disputed miasma theory, rather than for his support of chloroform.

BIRTH OF PRINCESS BEATRICE AT BUCKINGHAM PALACE

Main Points

• Chloroform was administered to Queen Victoria for the birth of Beatrice on Tuesday, April 14, 1857.

• The labor occurred about two weeks later than was expected.

• At about 2 A.M. the labor started and the medical men, including Drs. Locock and Snow, were sent for.

• Between 9 and 10 A.M., Prince Albert administered "very little" choloroform to the Queen on a handkerchief.

• At about 10 A.M. Dr. Locock administered a "birthing powder" to induce uterine contractions.

• At 11 A.M. Dr. Snow poured about 8 drops of chloroform on a cone-folded handkerchief, used for each pain.

• At about Noon, Dr. Locock administered a second dose of "birthing powder" and the pains increased.

• Complaining of pains, the Queen asked for more chloroform, continued to push and occasionally slept.

• Near 1 P.M. the head of Beatrice was resting on the area between the anus and the vulva.

• Dr. Snow stopped chloroform application for 3 or 4 pains, and the Queen made another pushing effort.

• Chloroform was given by Dr. Snow just as the head was expelled. Several minutes later Beatrice was entirely born.

• About 10 minutes after that, the placenta was expelled.

• The Queen's recovery was very favorable.

The Case Report

Written by Dr. John Snow after administering chloroform to Queen Victoria during the delivery by the attending physician, Dr. Charles Locock.

Tuesday, April 14, 1857

Administered Chloroform to Her Majesty the Queen in her ninth confinement. The labor occurred about a fortnight later than was expected. It commenced about 2 A.M. of this day, when the medical men were sent for. The labor was lingering, and a little after 10 Dr. Locock administered half a drachm of powdered ergot, which produced some effect in increasing the pains. At 11 o'clock I began to administer chloroform. Prince Albert had previously administered a very little chloroform on a handkerchief, about 9 and 10 o'clock. I poured about 10 minims of chloroform on a handkerchief, folded in a conical shape, for each pain. Her Majesty expressed great relief from the vapor. Another dose of ergot was given about twelve o'clock and the pains increased somewhat about twenty minutes afterwards. The Queen, at this time, kept asking for more chloroform, and complaining that it did not remove the pain. She slept, however, sometimes between the pains. Before one o'clock the head was resting on the perineum and Dr. Locock which the patient to make a bearing down effort, [1] as he said that this would effect the birth. The Queen, however, when not unconscious of what was said, complained that she could not make an effort. The chloroform was left off for 3 or 4 pains and the royal patient made an effort which expelled the head, a little chloroform being given just as the head passed. There was an interval of several minutes before the child was entirely born: it, however, cried in the meantime. The placenta was expelled about ten minutes afterwards. The Queen's recovery was very favorable.

[1] As before, Snow took especial care when writing here of his part in the Queen's confinement. However he, again, made a slip of the pen. Almost certainly he meant to write, "Dr. Locock wished the patient to make a bearing down effort."

Source: Ellis, Richard H. (ed): The Case Books of Dr. John Snow, Medical History, Supplement No. 14, Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, London 1994, p. 471.

CRITICAL REACTION TOWARDS THE LANCET, ONE CENTURY LATER

One hundred and three years after chloroform had been administered by Dr. John Snow at the births of Prince Leopold and Princess Beatrice, British anesthetist William Stanley Sykes (1894–1961) published his book, Essays on the First Hundred Years of Anaethesia. In it he presents his views on the reaction of The Lancet editor Thomas Wakely to the use of chloroform by Snow at the birth of Prince Leopold. Notice Sykes mention of the distiction between analgesia which refers to pain relief without loss of consciousness, versus anesthesia which is loss of physical sensation, sometimes including a loss of consciousness.

One hundred and three years after chloroform had been administered by Dr. John Snow at the births of Prince Leopold and Princess Beatrice, British anesthetist William Stanley Sykes (1894–1961) published his book, Essays on the First Hundred Years of Anaethesia. In it he presents his views on the reaction of The Lancet editor Thomas Wakely to the use of chloroform by Snow at the birth of Prince Leopold. Notice Sykes mention of the distiction between analgesia which refers to pain relief without loss of consciousness, versus anesthesia which is loss of physical sensation, sometimes including a loss of consciousness.

ESSAYS ON THE FIRST HUNDRED YEARS OF ANESTHESIA

In 1853 Mr. Wakley, the fearless and incorruptible watchdog of The Lancet, began to hear extraordinary rumours about Her Majesty, rumours which he could hardly believe.[4] Being Mr. Wakley he could not possibly ignore these tales, nor could he keep quiet about them. A leading article appeared:

"A very extraordinary report has obtained general circulation connected with the recent accouchement of her most gracious Majesty Queen Victoria. It has always been understood by the profession that the births of Royal children in all instances have been unattended by any peculiar or untoward circumstances. Intense astonishment, therefore, has been excited throughout the profession by the rumour that her Majesty during her last labour was placed under the influence of chloroform, an agent which has unquestionably caused instantaneous death in a considerable number of cases. Doubts on this subject cannot exist. In several of the fatal examples persons in their usual health expired while the process of inhalation was proceeding, and the deplorable catastrophes were; clearly and indisputably referrible (sic) to the poisonous action of the chloroform, and to that cause alone.

"These facts being perfectly well known to the medical world, we could not imagine that anyone had incurred the awful responsibility of advising the administration of chloroform to her Majesty during a perfectly natural labour with a seventh child." [It was, as a matter of fact, the eighth child]. "On inquiry, therefore, we were not at all surprised to learn that in her late confinement the Queen was not rendered insensible by chloroform or by any other anaesthetic agent. We state this with feelings of the highest satisfaction. In no case could it be justifiable to administer chloroform in perfectly ordinary labour; but the responsibility of advocating such a proceeding in the case of the Sovereign of these realms would, indeed, be tremendous. Probably some officious meddlers about the Court so far overruled her Majesty's responsible professional advisers as to lead to the pretence of administering chloroform, but we believe the obstetric physicians to whose ability the safety of our illustrious Queen is confided do not sanction the use of chloroform in natural labour. Let it not be supposed that we would undervalue the immense importance of chloroform in surgical operations. We know that an incalculable amount of agony is averted by its employment. On thousands of occasions it has been given without injury, but inasmuch as it has destroyed life in a considerable number of instances, its unnecessary inhalation involves, in our opinion, an amount of responsibility which words cannot adequately describe. "We have felt irresistibly impelled to make the foregoing observations, fearing the consequences of allowing such a rumour respecting a dangerous practice in one of our national palaces to pass unrefuted. Royal examples are followed with extraordinary readiness by a certain class of society in this country."

When I first came across this article I was almost as astonished as Mr. Wakley was, but for a different reason. The first thing to notice is the date — five weeks after the birth of Prince Leopold on April 7th, 1853, so the article obviously refers to this confinement. I checked these details very carefully to make certain that they were correct. This led to further researches into Victoriana, in an effort to explain a conflict of evidence.

The Lancet not only makes it clear that chloroform in normal labour is never justified under any circumstances, but it also states definitely, as a fact, that it was not used. This surprised me very considerably, for I knew that Benjamin Ward Richardson, in his long biographical preface to John Snow's book on chloroform,[5] states categorically that Snow gave chloroform to Her Majesty at this very confinement on the date mentioned above. "A note in his diary records the event. The inhalation lasted fifty three minutes. The chloroform was given on a handkerchief in fifteen minim doses, and the Queen expressed herself as greatly relieved by the administration. He had previously been consulted on the occasion of the birth of Prince Arthur in 1850, but had not been called in to render his services. . . . On April 14th, 1857, another note in his diary records the fact of the second administration to her Majesty, at the birth of the Princess Beatrice."

That sounds authentic and detailed enough, and it is in flat contradiction to The Lancets leading article. What is the explanation of this discrepancy? Was John Snow a liar, or did Richardson forge the entries in his diary, or was the usually reliable Mr. Wakley mistaken?? I think the last of these three alternatives is the correct one, and there is a certain amount of evidence and a good deal of presumption, to support this view, whereas there'is none whatever in favour of the other two theories.

AN OBSTETRICAL SCYLLA AND GHARYBDIS

[Greek mythology: two monstrous perils that sailors had to navigate in the Strait of Messina].

I say Mr. Wakley was mistaken. What I really mean is that he was deliberately misled.

The obstetrician and the other Royal doctors were in a very perilous dilemma. They were between the devil and the deep sea, so they quibbled. On the one hand was their illustrious patient, who probably demanded chloroform. And when Victoria asked for something she was in the habit of getting it. Her very decisive victory over the German Royal House in the matter of the marriage is distinctly relevant here. If she could bulldoze a crowned head in this effortless way, surely the opposition of a few doctors was child's play to her. After all, only a few years before doctors were expected to use the tradesman's entrance at the back of the house, if indeed they had altogether ceased this habit.

Also a person with a will like hers was not likely to hesitate in making up her mind very definitely on the question of chloroform for her own confinement. No doubt, as The Lancet says, the royal doctors were very reluctant to use it. The reasons against it, put forward by Mr. Wakley, were not new to them. They were common knowledge, and a large percentage of doctors agreed with them, at that time. No doubt also the Queen and Albert would listen politely to their objections. After all they had had a lot of practice at listening. Politicians, statesmen, ambassadors, mayors, and deputations of all kinds had been talking at them for years. But I imagine the end of the discussion was in character. "Thank you, gentlemen, for your opinions. We are having this baby, and We are having chloroform." And another question was settled and closed. I find it quite impossible to imagine the doctors persisting in their refusal in the face of that imperious and inflexible will.

On searching through the relevant parts of the nine volumes of the Letters of Queen Victoria I could find no direct reference to this incident [6]. These letters are, of course mainly political, written to her ministers. A few personal and family details are mentioned in those addressed to her relatives, especially those to her uncle the King of the Belgians. But she did not need to ask his advice on an intimate subject like this, which after all concerned nobody but herself and Albert.

On only one occasion — apart from her remarks to John Snow — did she record her opinion of chloroform, and it was entirely favourable. In a letter [7] to Princess Augusta, the mother of the Prince Frederick who married her eldest daughter, also called Victoria, she said, "Vicky appears to feel quite as well and to recover herself just as quickly as I always did. What a blessing she had chloroform! Perhaps without it her strength would have suffered very much."

It must be remembered that, conservative though she was in some ways, in others she was far in advance of her time. In an era when ladies of quality were kept in bed for weeks after their confinements she put into practice — no doubt against strong opposition — the modern idea of getting up early. The Prince Consort himself makes this quite clear in a letter to his stepmother after the birth of the Princess Beatrice (the occasion of the Queen's second anaesthetic): "Victoria is already on the sofa and very well." [8] The birth was on the 14th April and the letter was written on the 19th.

Sidney Lee's biography [9] and Queen Victoria's own book [10] do not mention chloroform at all. There is no particular reason why they should. So the probability is that the accoucheur [ one who assists at a birth] had to do as he was told, making the best of a bad job by unloading the terrific burden of responsibility on to the competent shoulders of John Snow. He was the acknowledged expert, and had been ever since the beginning of anaesthesia — the only anaesthetist in the kingdom, with the possible exceptions of Clover and Potter.

But imagine the accoucheur's horror at the thought of what the formidable Mr. Wakley would say. For he was the other horn of the dilemma, and he was in his own way as inflexible as the Queen herself. Nothing would induce him to be quiet if he had something to say, and he had seen to it that his opinions about chloroform were generally known amongst his professional brethren. He was unbribeable, incorruptible, and utterly fearless. Rank, position and power meant nothing to him, nor was he afraid of the law. Chloroform in normal labour he condemned utterly as a treacherous drug — not knowing yet that it was far safer in labour than in surgery. Mr. Wakley was perhaps even more intimidating than the Queen — if that were possible — for there is no evidence that he ever softened or mellowed at all, whereas Victoria occasionally did. So he had to be pacified by a half-truth—that the Queen was not rendered insensible, which Mr. Wakley interpreted, as he was intended to do, as not having chloroform at all. In actual fact the Queen got her chloroform, given by the best possible man, but she got analgesia only, not anaesthesia — chloroform it la reine [Queen Victoria's use of chloroform as an anesthetic during childbirth], in fact. Snow knew quite a lot about anaesthesia by this time, quite enough to use analgesia deliberately. His fifteen minim doses were in fact designed for this purpose, and they did their work well. The Queen herself said so. Mr. Wakley's conjecture that "a pretence of giving chloroform" might have been used was unworthy of his intelligence. Was Victoria the sort of person to be tricked like this?

Technically correct the statement may have been, but as an example of hair-splitting casuistry it takes some beating. For the Editor of The Lancet was certainly left with a totally wrong impression. He goes on to pontificate, "In no case could it be justifiable to administer chloroform in normal labour."

Not a very creditable episode, really. One wonders if Victoria and Albert ever got to hear about it. Probably not. It is very unlikely that they had either the time or the inclination to read The Lancet. It is equally unlikely that anyone would dare to tell them about it. Anyway John Snow was employed again at a future confinement, so it is quite certain that his work met with the royal approval. But it cost me several weeks of work to ferret out the facts and the background of this affair and to explain the incident in a reasonable way. I can think of no other theory which fits the facts. Whether Mr. Wakley ever found out how he had been diddled is not yet clear. Further researches in later numbers of The Lancet should clear up this point.

A detailed search through later volumes, carried out after this chapter was written — I couldn't delay the writing of it because it interested me so much — revealed no further mention of this anaesthesia.

What it did reveal was the fact that I was not quite accurate when I stated that Mr. Wakley never mellowed at all. He, or at any rate his paper, became rather less forthright and less intimidating than before. In 1857 two of his sons were made partners in The Lancet. Five years later he died, at the age of sixty-seven. Perhaps he was getting a little tired of fighting, perhaps his sons had a restraining influence. After all, he had corrected so many Abuses, defended so many libel actions, exposed so many scandals and advocated so many reforms that the old fire within had probably died down to some extent.

On April 18th, 1857, the year of the family partnership, The Lancet reported that "Her Majesty was safely delivered of a Princess . . . on Tuesday last." It was a normal labour, but the report goes on to state, quite calmly, that Dr. Snow began to give chloroform at intervals at 11.30 a.m. This continued for 2 J hours, and "the anaesthetic agent perfectly succeeded in the object desired."

But there was no further comment and no criticism of any kind. I seem to detect the influence of the brothers Wakley here, rather than that of their ruthless and caustic father. In the next week's issue there is a simple and gratified report that Dr. Locock, "who has assisted Her Majesty through so many hours of trial without the occurrence of a single mishap," had been rewarded with a title and had become Sir Charles Locock, Bart. Sir Charles, then plain Dr. Locock, was appointed physician accoucheur to Her Majesty in 1846. She had had four children before this. In 1847 Dr. Robert Ferguson was also appointed to a similar position. So these two were probably responsible for her last five confinements. Victoria had one other operation during her long life, on Sept. 4th, 1871. Mr. Lister opened an axillary abscess for her, but the reports do not mention any anaesthetic.

Many years later, however, in 1908, [11] Lord Lister, in a long letter to Sir Hector Cameron, gave a condensed history of his antiseptic method. He began by saying that he first treated compound fractures with undiluted carbolic acid in 1865. He then began to use it for abscesses. "I continued to use a strip of lint as a drain for about five years with perfectly satisfactory results. But in 1871, having opened a very deeply seated acute abscess in the axilla, I found to my surprise on changing the dressing next day that the withdrawal of the lint was followed by escape of thick pus like the original contents. It occurred to me that in that deep and narrow incision, the lint, instead of serving as a drain, might have acted as a plug and so reproduced the conditions present before evacuation." He goes on to describe in detail how he cut off a piece of rubber tubing from the Richardson's ether spray which had been used at the operation, cut holes in it and attached silk threads to one end. He then soaked it in strong carbolic solution all night and used it for the abscess next morning. He found that there was no further damming up of pus, and the abscess healed in a week. After that he continued to use drainage tubes instead of lint plugs.

Was this patient Victoria? It was the right year, and he goes into such detail that it might well have been the Queen's case. Or it may have been that he detailed it because he thought tubes were a great advance over the old method. We shall never know for certain. But the case does give a hint as to the anaesthesia used. It would certainly be the ether spray.

Much later another little sidelight on this operation was discovered. Sir St. Clair Thomson, one of Lister's house surgeons many years before, gave an address in 1927,[12] revealing many interesting and homely facts about his old chief. In the course of it he said: "Like all great men he was keen on the importance of small details. In showing us how to bandage a breast he insisted on the point that, in spite of various turns, the bandage was almost sure to slip . . . if the . . . turns of the bandage, above and below . . . the mamma . . . were not prevented from slipping up and down by uniting them with a safety pin. . . . To impress this point upon us he narrated that he had once had to open a simple abscess in the axilla for Queen Victoria. All went well. After one dressing and on arrival at the railway station to travel back to Edinburgh, he suddenly remembered that he had forgotten the important safety pin. He at once drove back to the Castle, and explained his oversight to Her Majesty, and the necessity for rectifying it. Some surgeons, I fear, would have thought first of their own reputation, and would have 'risked' the safety pin."

I have read enough about Victoria to convince me that Lister's frankness and courage in acknowledging his forgetfulness would be appreciated by the patient. Albert would certainly have approved, but, alas, Albert was no longer there.

After her second general anaesthetic Victoria had still a few years of perfect happiness with her beloved, before she entered the gloomy and weary thirty-nine years of loneliness and sorrow. Only as death approached did the shadows lighten, at the joyous prospect of reunion. When she was dead there was to be no black upon her, for the first time for four long decades. So, at eighty-one, she was buried with her wedding veil in her coffin.

Dr. Locock had the vastly increased professional prestige of his baronetcy, Mr. Wakley, though still alive, lay dormant like an extinct volcano, and Dr. Snow, being an anaesthetist, naturally got nothing out of it at all.

Sources:

Caton, D. Anesthesiology 92m 247-52, 2000.

Ellis, RH. Medical History (Supp 14), 1994.

Sykes, WS. Essays on the First Hundred Years of Anaesthesia. Vol. 1, pp. 79-85, E. and S. Livingstone, 1960 [First Edition (January 1, 1960].(internal references below)