Stream 4 - John Snow's Life

c: John Snow's Professional Years

TIME SUMMARY

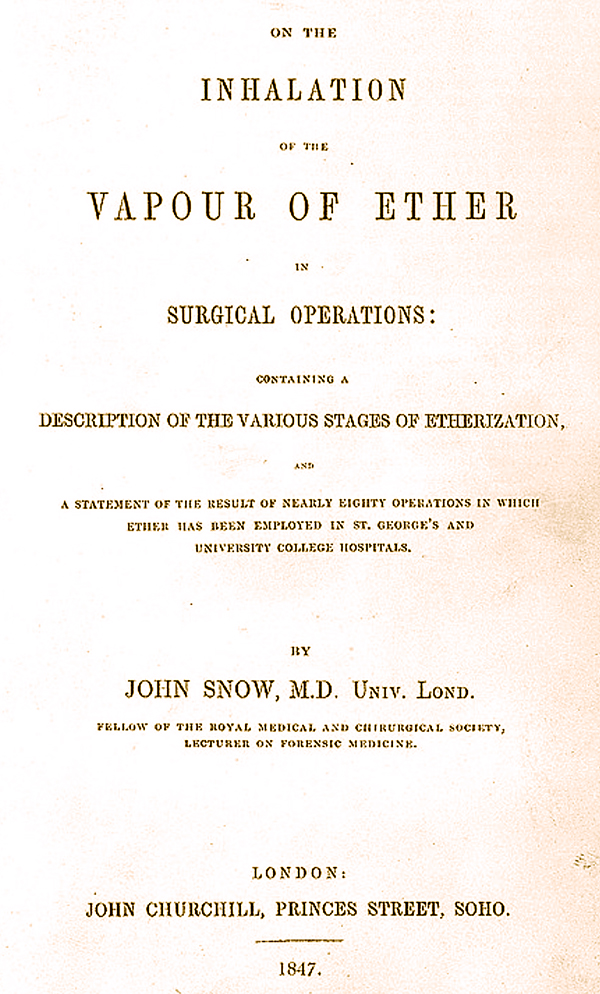

1847. At age 34 with his M.D. degree in hand, Snow became an anesthetist at both St. George's Hospital and University College Hospital. While there, he published his first book, On the Inhalation of the Vapor of Ether in Surgical Operations detailing the results of nearly 80 operations in which ether was used at the two hospitals. In the same year, as described before, he published a series of articles on ether in various medical journals.

1848. Snow constructed an inhaler for chloroform, another anesthetic agent.

1849. Snow published in August the first edition of of his booklet On the Mode of Communication of Cholera.

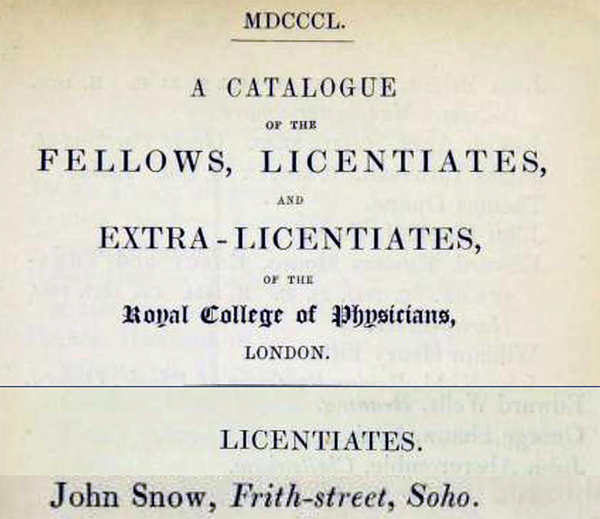

1850. Snow was admitted to the Royal College of Physicians of London, receiving his licentiate (licensed specialist - LRCP). He also became a founding member of the Epidemiological Society of London.

1851. Snow was appointed physician at the Hospital for Consumption and Diseases of the Chest in Brompton, south of London.

1852. Snow at age 39 moved into a more spacious home at 18 Sackville Street, still in the same neighborhood.

1853. At age 40, Snow administered chloroform to Queen Victoria during the birth of Prince Leopold.

1854-55. He was involved with the Broad Street pump outbreak and urged the Board of Guardians to remove the handle of cholera-contaminated pump. South of the River Thames in London, he conducted concurrently the classic grand experiment

comparing the mortality of patrons of two water companies, one exposed to cholera and the other not.

1855. Snow published the second more complete edition of his book On the Mode of Communication of Cholera. Also that year, he was elected President of the Medical Society of London.

1857. At age 44, Snow again administered chloroform to Queen Victoria, but this time during the birth of Princess Beatrice.

1858. At midyear on June 16th, Snow died in London. He was 45 years old. His new book, On Chloroform and Other Anaesthetics was published posthumously.

PROFESSIONAL CAREER

Snow was very active in his professional career, starting with anesthesia at the individual level and ending with cholera at the population level. Besides being interested in all aspects of anesthesia, he focused his research mainly on ether and chloroform, including in the design of apparatuses to deliver the anesthetic agents, based on his extensive research.

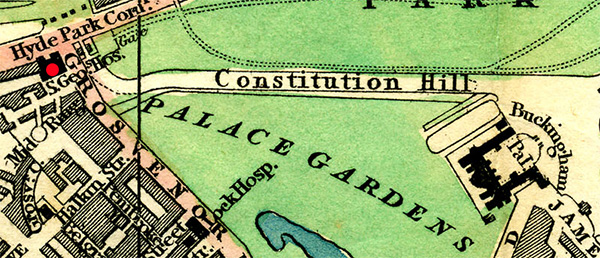

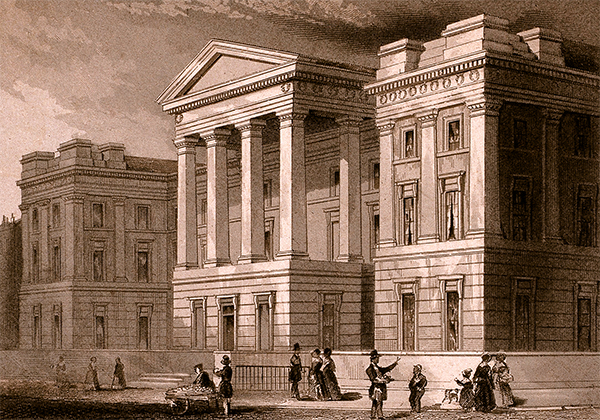

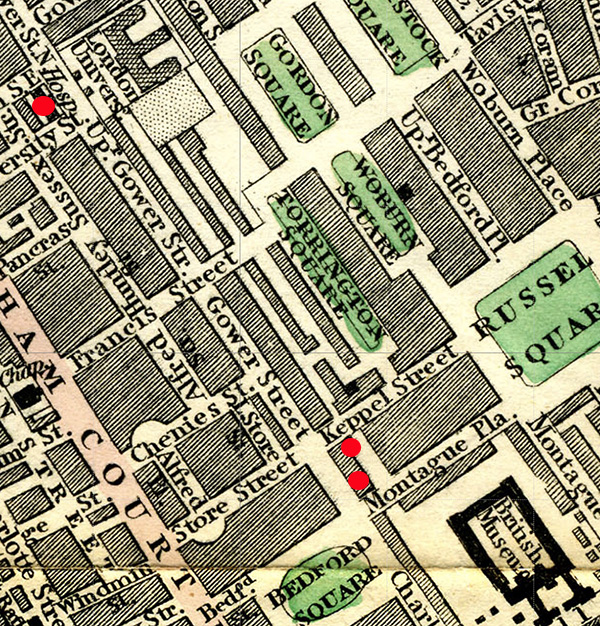

St George's Hospital on Hyde Park Corner (see red dot on Crutchley's 1846 map below and image below) near the Buckingham Palace was a new 350 bed facility, completed in 1844, two years before John Snow's arrival as anesthetist in 1846 at the beginning of his professional career. At the time he was patching together his private practice at his Frith Street home, lectureship at Aldersgate School of Medicine and anesthesia, with appointments at both St. George's and University College hospitals.

ST. GEORGE'S HOSPITAL

After demolishing the old Lanesborough House at Hyde Park Corner, architect William Wilkins designed for the location the new 350 bed St. George's Hospital, completed in 1844. The hospital is close to Buckingham Palace.

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE HOSPITAL

Famed surgeon Robert Liston in 1846 performed the first major operation with ether in Europe at the University College Hospital. Soon thereafter, John Snow became actively involved in understanding the safety and utility of ether.

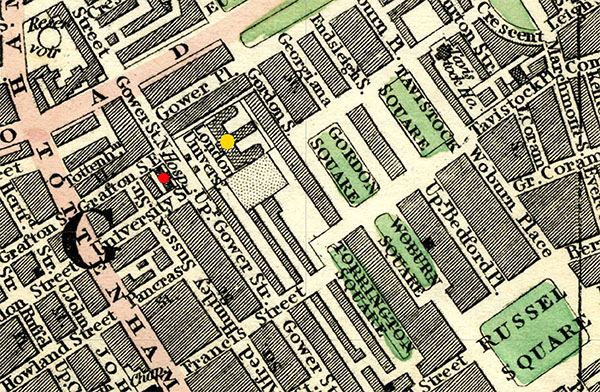

ETHER

Earlier in late 1846 while tending as anesthetist at University College Hospital (top red dot at right), John Snow had first learned of a new anesthetic agent, ether. Francis Boott, a retired American physician living in London on Gower Street ( bottom red dot at right) received a letter from an American colleague describing a successful tumor operation done by a Boston dentist with ether as the anesthetic agent. Boott shared this news with James Robinson (middle red dot at right), a highly respected surgeon-dentist living close by, and asked him to collaborate. Robinson agreed. On December 19, 1846, in the home-study of retired American physician Boott, surgeon-dentist Robinson succesfully used ether for a tooth extraction on a young woman.

In the ensuing weeks, Robinson gave several demonstrations of his technique. Attending to understand and learn the specific technique, was famed surgeon Robert Liston of University College London (upper red dot at right). On December 21, 1846 with many influential people in attendance, surgeon Liston at University College hospital immediately did two operations using ether. Still another week went by before John Snow, on December 28, 1846, was able to observe first-hand when dentist Robinson successfully did another operation.

A year later, surgeon Robert Liston died on December 7, 1847. Out of respect for his surgical mentor and interest in ether, John Snow carried on with extensive research on the new agent.

Using a home laboratory with various small birds (thrushes and linnets), pigeons, guinea pigs, rabbits, white mice, goldfish, frogs and small dogs and cats, Snow began to determine the proper dosage of ether taking into account temperature.

He then created an apparatus for controlling temperature during the inhalation of ether.

Starting in January 1847, Snow shared this information at several meetings of the Westminster Medical Society, offering theories, then with experimentation, refining them in laboratory and clinical settings. Snow also published his laboratory experiments throughout the year in several medical journals.

By September 1847, he was ready to publish a book on ether. At St. George's Hospital, Snow had administered ether 52 times, while at University College Hospital he administered the agent 23 times. These "nearly 80 operations in which ether had been employed" became the basis of his new book (see publication #27. at Stream1_introduction_d).

In the two years that followed Robinson's demonstration, Snow's reputation as an anesthetist soared, and he became in frequent demand by local surgeons. His research on the properties and applications of ether continued as well, followed by his publication in 1847 On the Inhalation of Ether, to guide the use of the anesthetic agent. Among the many applications was anesthesia for childbirth.

But then chloroform came along.

Chloroform drop flask

Chloroform drop bottle with a control valve

Chloroform drop flask

Source: Wood Library Museum of Anesthesiology, Schaumburg, Illinois.

CHLOROFORM

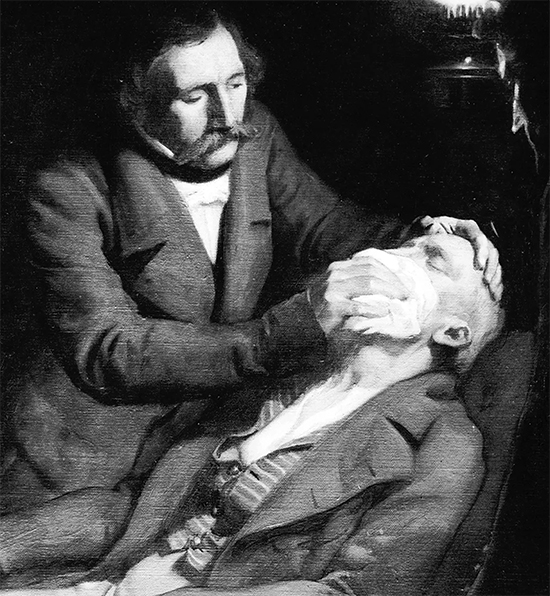

While Snow was focusing on ether and a new apparatus for better administration, most other practitioners were pouring by hand or droplet flasks their agent of choice on a cloth or sponge while holding it over the nose and mouth of the patient, followed by visual judgement of the induced anesthesia.

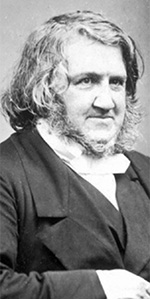

In 1847, an Edinburgh obstetrician, James Young Simpson, introduced chloroform. In studying chloroform, more potent than ether, Snow soon realized that both accuracy of delivery and patient monitoring were very important.

The usual method for administering chloroform was as before -- hold a saturated cloth or sponge over the nose and mouth of the patient, refreshed as needed, drop by drop from special flasks. Several died. Snow studied the various deaths and advocated in talks and publications that scientifically engineered vaporizers should be used instead.

Earlier, Snow had designed several inhalers for ether.

When chloroform came along, he invented a smaller, more portable, inhaler appropriate for the new anesthetic agent. As seen below, a cup surrounded the nose and mouth with a tube leading to two metal cylinders, one inside the other, that allowed air to become saturated with chloroform before entering the breathing tube. Since he had found that temperature has a major impact on the concentration of inhaled chloroform, the space between the inner and outer cylinder contained water, held at a constant temperature of about 60 degrees Fahrenheit (15.5 degrees Celsius).

James Y. Simpson, M.D.

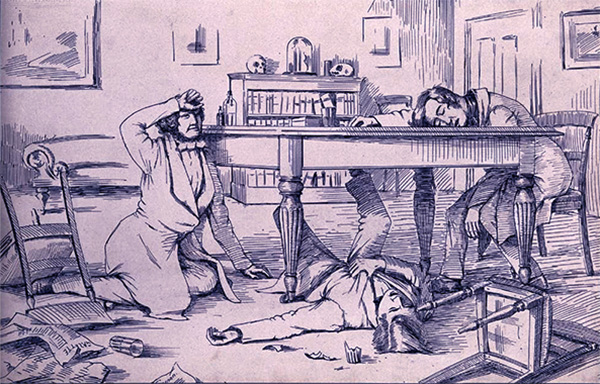

On November 10, 1847, Simpson described his experiences with chloroform to the Medico-Chirurgical Society of Edinburgh. While he reported using chloroform successfully in fifty or so cases, he amused the audience with mention of an early experiment with two friends drinking chloroform rather than inhaling the vapor. In a drawing made of the story, there is a shattered drinking-glass lying next to one friend, while the other had already passed out. Inhalation was found by Simpson to be more effective as an anesthetic agent than a social imbibing agent.

Source: Wellcome Foundation and Wellcome Historical Medical Museum

Royal College of Physicians, London

The Royal College of Physicians, London was the London chapter of a medical organization formed to emphasize the importance of high standards in medical practice. The first of two levels of certification was for Licentiates (licensed specialist, termed "LRCP"). The organization's oral examinations, held in Latin since 1849, were offered at three month intervals. Fortunately for John Snow, as a youngster he had studied both Latin and Greek in York at the Dodsworth School at Bishop Hill. There was also a written examination, again in Latin.

The examination was given to John Snow in 1850 by four examiners and the organization's president at the organization's building on Pall Mall East, near Trafalgar Square.

The five examiners were charged with "maintaining the standards and integrity of the medical profession." Given Snow's intelligence, academic background and his dedication to medical research and practice, it's very likely that he passed the Licentiate examination on the first try.

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON

John Snow was a founding member of the Epidemiological Society of Londo , one of the first professional organizations devoted to the field of epidemiology. The seal of the organization (see figure) includes the Latin phrase penned by the Roman poet Persius (34-64 AD), venienti occurrite morbo, translated into English as confront disease at its onset.

How did this important movement get started? What were their contributions during Snow's life, and in the years that followed?

Origin of Society

In February 1848, three and a half years after John Snow received his M.D. degree, an intriguing letter to the editor appeared in The Lancet. England at the time was very concerned with the possible appearance of a second cholera epidemic (the first ever occurred in 1831-32). The letter started, "Will that dreadful scourge the cholera visit our island again? If so, are medical men prepared to wage a war against it?" The letter proceeded to suggest that "meetings [to address this disease] should be held in different localities." Finally the letter concluded with the suggestion that medical journals should report "a statistical account of deaths and recoveries." The signer was mysteriously identified as "Pater" (a British term for father).

In July 1849, after cholera had again appeared in England, the same Pater wrote once more to The Lancet, but this time to propose "...the formation of a new society, which might be styled the Asiatic-Cholera Medical Society, or the Epidemic Medical Society, the object of which would be to investigate epidemics..."

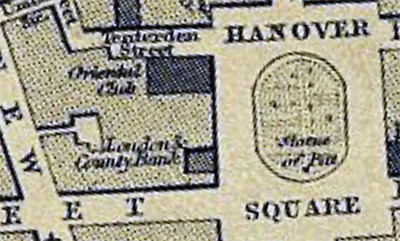

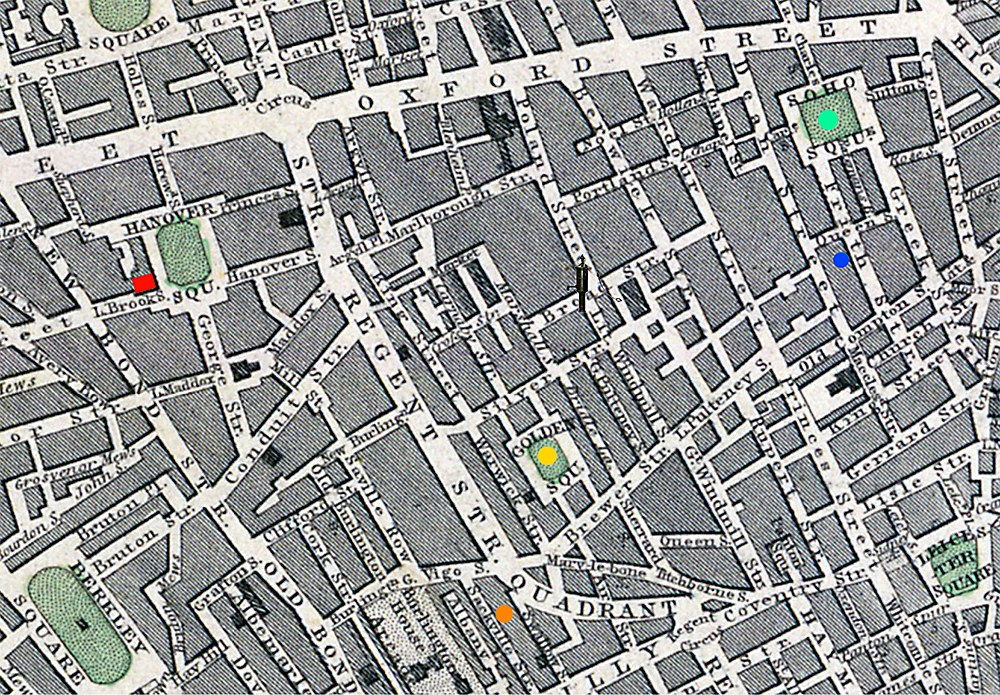

The identity of Pater was finally revealed in The Lancet as J. H. Tucker, a concerned physician practicing in London. His stimulating words lead to a meeting on March 6, 1850 in Hanover Square, within walking distance of the Broad Street pump in the Soho region of London. It was here that the Epidemiological Society of London was born, in the corner building at 21 Hanover Square W1 (see red tinged building below and red square in following map north of Brooks Street in the southwest corner of Hanover Square).

The building where the Epidemiological Society of London was meeting had just been remodeled in 1850. In 1856 the Western Bank of London was established at this address, but then acquired in 1859 by the London and County Banking Company. The latter is apparent nine years later in the Weller Map of London, 1868. Just to the right in the above photo is 20 Hanover Square (grey building) where the Medical Society of London held its initial meetings.

While not so stated, it seems likely that both banks continued over the years to provide monthly meeting space for the Epidemiological Society of London.

.

Also presented is Davies London Map of 1843, showing the walking distance to Hanover Square (John Snow enjoyed this form of exercise). Soho Square is identified with a green dot), closeby is Snow's second home after mid-1838 at 54 Frith Street (blue dot). The Broad Street pump sits in front of 40 Broad Street (black symbol). Close by is Golden Square (gold dot) and Snow's third home from 1852 at 18 Sackville Street (orange dot).

A second meeting was held in the same temporary building in Hanover Square on July 30, 1850 to create a constitution and appoint the founding members and officers. The first president was Dr. Benjamin G. Babington (shown at right), a prominent physician at Guy's Hospital in London and member of the medical board that was expected to advise the London government on ways to address the cholera epidemic. John Snow also attended this organizing meeting of the Epidemiological Society of London and is considered one of the founding members. He was 37 years old.

After another four months had past, Dr. Babington held on December 2, 1850 the first professional meeting of the Epidemiological Society of London, 33 months after the initial Pater letter appeared in The Lancet About 100 members and visitors were present. Among the most famous were Thomas Addison (1793-1860), the British physician who discovered pernicious anemia (now termed Addison's anemia) and adrenal cortex deficiency (now called Addison's disease); and Richard Bright (1789 -1858), his British colleague who first described the disease characterized by edema and presence of albumin in urine, now termed Bright's disease.For others, including John Snow, fame would come later. Notable in this latter group was Dr. John Simon (at left), who in 1848 had become the first medical officer of health of London (he remained in that position until 1855); and Gavin Milroy who in 1864 on Babington's retirement, would become the second president of the Epidemiological Society of London.

ORIGINAL PURPOSE OF THE ORGANIZATION

When the constitution of the Epidemiological Society of London was created, the founders had three major purposes all related to epidemics as a broad notion, not specific to a cholera epidemic, the threat of which had stimulated the earlier letters of Pater.

1) to institute rigid examination into the causes and conditions which influence the origin, propagation, mitigation, and prevention of epidemic diseases;

2) to institute...original and comprehensive researches into the nature and laws of disease; and

3) to communicate with government and legislature on matters connected with the prevention of epidemic diseases.

The founders also recognized that having ideas without public or professional communication is a self-centered undertaking. To avoid this end they advocated:

1) to publish original papers,

2) to issue queries,

3) to publish reports,

4) to form statistical tables,

5) to prepare illustrative maps, and

6) to collect works relative to epidemic diseases.

These purposes and undertakings remain appropriate today.

Papers were regularly presented at the monthly meeting of the Epidemiological Society of London such as one in 1851 on the use of statistics and statistical methodology in the study of epidemic diseases. Between 1851 and 1853, most meetings had considerable discussion about whether or not a specific disease was caused by a contagion, with cholera and yellow fever being common example cited by both opponents and proponents of the germ theory (i.e., disease is caused by a microorganism or germ).

In 1853, the same year he administered chloroform to Queen Victoria during the birth of Prince Leopold, John Snow presented a paper on "The Comparative Mortality of Large Towns and Rural Districts, and the Causes by Which it is Influenced" which featured the application of statistics to epidemiology.

In 1852, Dr. Benjamin W. Richardson (at left), a close friend of Snow's, joined the Epidemiological Society of London. Being an intellectual comrade, Dr. Richardson supported Snow in his theory of water propagation of cholera, an idea that was not quickly accepted by the medical community. Later after the death of his friend in 1858, Richardson would write the lengthy account of Snow's life that enriches our current understanding of the life and times of the man ( for further details on Richardson's memory of Snow, go to Stream 1_introduction_e).

Richardson founded the Journal of Public Health in 1855. Four years later, however, the public health journal was discontinued for financial reasons. Thereafter the Society published its own proceedings as the Transactions of the Epidemiological Society of London, which remained until 1907.

John Snow, President of the Medical Society of London

Also in 1855-56, John Snow was President of the Medical Society of London, which in 1850 had merged with the Westminster Medical Society, long favored by Snow. The organization had moved to 32a George Street, south of Hanover Square (green dot), not far from 21 Hanover Square (red rectangle) where the Epidemiological Society of London held its meetings.

In 1861, three years after the death of John Snow, Gavin Milroy presented "The Influence of Contagion on the Rise and Spread of Epidemic Diseases." In this important work he joined John Snow in dismissing the miasmatic theory of disease causation (i.e., the idea that poisonous atmosphere rises from swamps and putrid matter and causes disease) because of its inconsistency with the spread of epidemics.

DEMISE AND REBIRTH

At the end of the century as infectious diseases continued their inevitable decline, the Epidemiological Society of London came to a temporary end. Its successor was the Section on Epidemiology and State Medicine of the Royal Society of Medicine. Later still this became the Section on Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, also of the Royal Society of Medicine. In more modern times, emphasis was placed on prevention of such non-infectious conditions as accidents involving motor vehicles, heart disease, cancer and even mental illness. In addition, this new section of the Royal Society of Medicine stressed the use of quantitative epidemiological methods and principles, and held discussions on topics such as ethical questions relating to public health. Likely if John Snow had lived to the present, he would have approved, and enthusiastically participated in the continuing story of epidemiology.

Drs. John Snow and William Budd - Collaborators or Competitors?

Dr. John Snow published his small booklet On the mode of communication of cholera on August 29, 1849. It was subsequently reviewed in the London Medical Gazette on September 14, 1849.

Shortly thereafter on September 27, 1849, Dr. William Budd in Bristol, well west of London, published a similar book, Malignant cholera: it's mode of propagation. A day earlier on September 27, an abstract from the opening pages appeared in The Times London.

Both books dealt with cholera. Snow's main hypothesis was that cholera was a fecal-oral disease transmitted by contaminated water. He also felt that cholera was likely caused by a microbe of some form or another, but had no specific agent in mind.

William Budd (1811-1880, see at left) supported the hypothesis that contaminated water was the source of much cholera, but felt that contaminated air might be involved with some cholera. Rather than focusing vaguely on a microbe, Budd and his Bristol medical colleagues focused on a fungus-like organism that had been observed in the stools of cholera patients, thinking it to be the agent of the disease. While both Snow and Budd developed their theories around the same time, Budd acknowledged that Snow was the first to publish the hypothesis (if only by a month) that contaminated water was a major source of the disease.

In general, the two agreed on the theory of waterborne cholera, calling into question the prevailing miasma theory of putrified matter and unapealing odors. For more details on John Snow's thoughts about William Budd, see what he wrote in a Letter to the Editor of the Edinburgh Medical Journal of January 1856, posted as reference #98 in Stream 1 d: John Snow's Publications.

Hospital for Consumption and Diseases of the Chest

In 1851, Snow was appointed physician for about two years at the recently upgraded Hospital for Consumption and Diseases of the Chest in Brompton, south of London, fronting Fulham Road (at left), a short distance northeast of the Brompton Cemetery where he would take his final rest. The hospital opened for patients in 1846, with a special feature being the ventilation system flowing warm air through the wards from floor vents to ceiling valves.

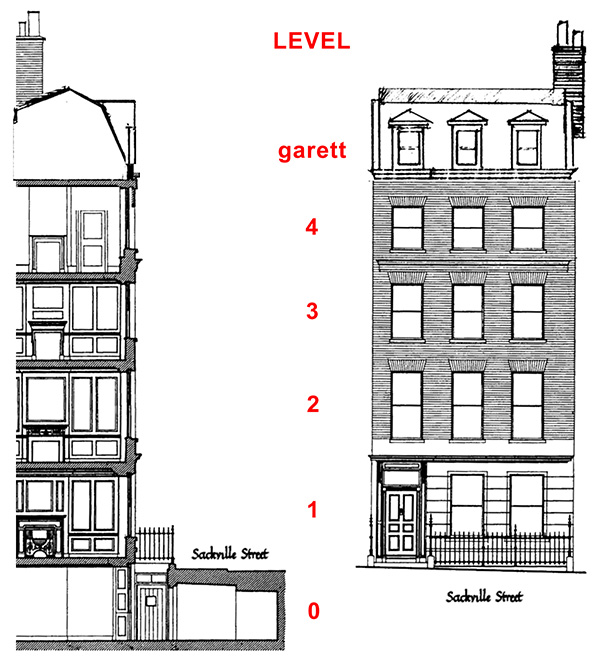

NEW HOME

In 1852, Snow moved to his third and final home at 18 Sackville Street, an affluent region of the city west of Golden Square. While maintaining a small general practice, he had become much more successful as an anesthetist and researcher with 51 publications, attesting to prominence in the medical community. His new house is shown at right in part-side and front silhouettes. There were two people living in the house, Snow and his long-term housekeeper Jane Weatherburn.

Starting at the bottom, the home had a basement that extended below the street. Rising up from the basement to the garett (or attic) is a dog-legged staircase (a flight of stairs ascending to a half-landing before turning 180 degrees and continuing upwards). Level 0 or the basement had a kitchen, larder (a cool area for storing food prior to use), vaults and a wash-house. Level 1 had a parlor and a surgery room. Snow used the parlor for his small general practice to see and treat patients. On level 2 was a dining room next to a morning room for seeing special visitors and personal reflection and relaxation. Level 3 held Snow’s bedroom and study, the later at the front of the house with natural light streaming in. Finally, level 4 was the housekeeper's quarters, and the garett was used for his research activities, including a laboratory and a room to house small animals for experimentation.

18 Sackville Street

During the six years that Snow lived in this accommodating final house (1852-1858), his reputation soared and he nearly doubled his list of professional publications, totalling 125 at the time of his death. In all, he was the sole author.

QUEEN VICTORIA

On April 7, 1853, Queen Victoria asked John Snow to administer chloroform for the delivery of her eighth child, Prince Leopold. This was such a success that it was repeated for the delivery of Princess Beatrice 4 years later. With the royal blessing, general acceptance soon followed. More detail are coming in Stream 4 d: Anesthesia for Queen Victoria.

MAJOR BOOK ON CHOLERA

While anesthesia and general medicine paid the bills, John Snow's other interest in the epidemiology of cholera increasingly came to the fore. In 1849 he published a thin book on the communication of cholera, deemed the first edition, outlining some of his ideas about the disease (see previously). Then following multiple epidemiological investigations, including the Broad Street pump outbreak and the "Grand Experiment," he published his more extensive second edition in 1855, as shown below.