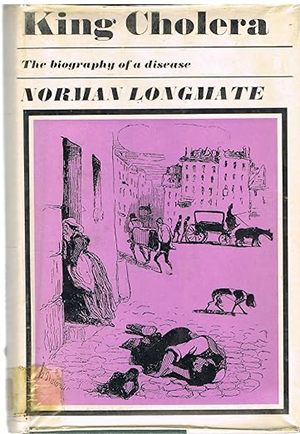

In his past book, King Cholera, Norman Longate (1925-2016) provides a fine overview in an engaging tone of John Snow's life and contributions, summarizing much of what has been presented in this website. His 10 pages in Chapter 19 on John Snow reflect his writing style, crafted in 31 books during an active life time.

Source: Longmate, Norman. Victory in Sight, Chapter 19, 201-211 in Longmate N. King Cholera - The Biography of a Disease, publisher H. Hamilton, London,1966.

I resolved to spare no exertion which might be necessary to ascertain the exact effect of the water supply on the progress of the epidemic.

- SNOW, M.D., On the mode of communication of cholera, 1855

Victory in Sight

The main burden of the fight against cholera in the British Isles had been borne by the humble, and usually underpaid, general practitioner. It was appropriate that the great discovery of how cholera was spread should have been made not by a high-powered official committee, or some flamboyant master of medicine, but by a shy, unfashionable doctor, who never achieved real eminence in his profession. Dr. John Snow had been born at York, the son of a farmer, in 1813, and at fourteen had been apprenticed to a surgeon in Newcastle.