Stream 5- Additional Items

d: Other Cholera Outbreaks

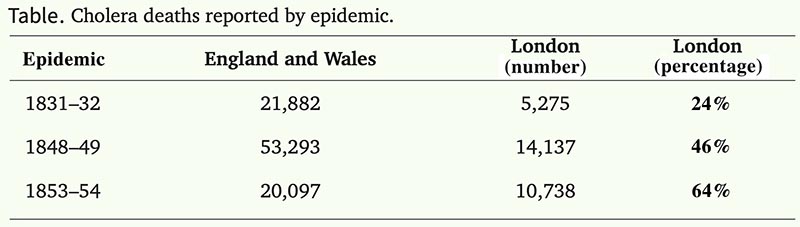

During John Snow's 45 years of life, his country was beset by three cholera epidemics: the first in 1831-32 experienced by Snow in the Killingworth colliery near Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and both the second 1848-49 and third 1853-54 epidemics while he was in London. While Snow's two major contributions to epidemiology occurred during the 1853-54 epidemic (i.e., Broad Street Pump Outbreak and The "Grand Experiment"), there are still four smaller cholera stories to be told, the first during the 1831-32 epidemic, the second and third during and around the 1848-49 epidemic and the fourth during the tail end of the 1853-54 epidemic.

Source: Creighton, C. A history of epidemics in Britain, vol. II. From the extinction of plague to the present time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1894.

1831-32 EPIDEMIC

STORY 1: The Ill-Fated Barnes Family (1832)

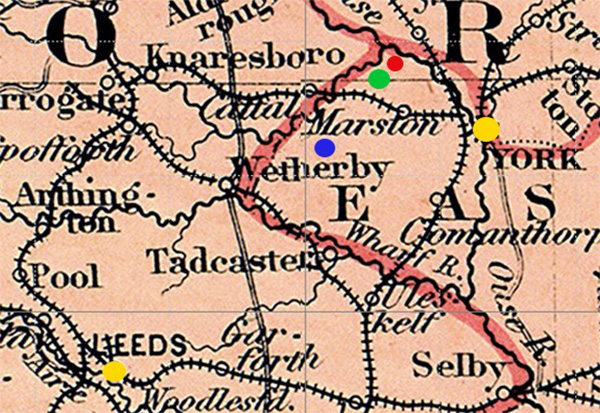

In his 1855 book, On the mode of communication of cholera. 2nd edition, John Snow attempted to identify how cholera was spread from one person to another. He first wrote of case-studies that had come to his attention. One such study was of John Barnes and his ill-fated family in 1832. The material came from a report, Observations on Asiatic Cholera, written by Dr. Simpson of York. The story involved five communities in the central region of England, as seen in the 1856 map: York (gold dot - right) where author Simpson lived, Leeds (gold dot - left) and Redhouse (red dot), Moor Monkton (green dot) and Tockwith (blue dot).

JOHN BARNES

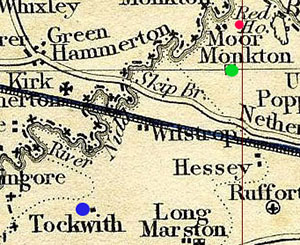

John Barnes lived in Moor Monkton (green dot - 1840 map), an agricultural village north-west of York where cholera had not previously appeared. Here is what John Snow wrote of John Barnes in his 1855 book:

"John Barnes, aged 39, an agricultural laborer, became severely indisposed on the 28th of December 1832; he had been suffering from diarrhea and cramps for two days previously. He was visited by Mr. George Hopps, a respectable surgeon at Redhouse (red dot - 1840 map), who, finding him sinking into collapse, requested an interview with his brother, Mr. J. Hopps, of York."

" This experienced practitioner at once recognized the case as one of Asiatic cholera; and, having bestowed considerable attention on the investigation of that disease, immediately enquired for some probable source of contagion, but in vain: no such source could be discovered. When he repeated his visit on the day following, the patient was dead; but Mrs. Barnes (the wife), Matthew Metcalfe, and Benjamin Muscroft, two persons who had visited Barnes on the preceding day, were all laboring under the disease, but recovered. John Foster, Ann Dunn, and widow Creyke, all of whom had communicated with the patients above named, were attacked by premonitory indisposition, which was however arrested.

The facts were at hand. John Barnes was dead. His wife and two friends who had contacted Barnes shortly before he died developed cholera but recovered.,Finally three persons who had contact with the two friends but not Barnes, became sick and recovered. While John Barnes seemed to have transmitted the disease to others who then passed it on to more people, how did Barnes become sick in the first place?

THE MYSTERY IS SOLVED

"Whilst the surgeons were vainly endeavoring to discover whence the disease could possibly have arisen,the mystery was all at once, and most unexpectedly, unraveled by the arrival in the village of the son of the deceased John Barnes. This young man was apprentice to his uncle, a shoemaker, living at Leeds (gold dot - upper map). He informed the surgeons that his uncle's wife (his father's sister) had died of cholera a fortnight before that time, and that, as she had no children, her wearing apparel had been sent to Moor Monkton by a common carrier. The clothes had not been washed; Barnes had opened the box [from his dead sister's household] in the evening [i.e., Christmas night] ; on the next day he had fallen sick of the disease."

To John Snow, this story suggested that cholera was spread both directly from person to person and indirectly by contact with contaminated objects. While Snow in his text did not mention an incubation period, for John Barnes it was likely the time between contact with the unwashed clothes and the first signs and symptoms of his infection, or one day.

The problems of John Barnes' family continue, due to the spirit of the human heart. When his wife, Mrs. Barnes, became sick sometime between December 26 and 29 and remained ill for days thereafter, her mother rushed to help.

"During the illness of Mrs. Barnes, her mother, who was living at Tockwith (blue dot), a healthy village five miles distant from Moor Monkton, was requested to attend her. She went to Moor Monkton accordingly, remained with her daughter for two days, washed her daughter's linen, and set out on her return home, apparently in good health. Whilst in the act of walking home she was seized with the malady, and fell down in collapse on the road. She was conveyed home to her cottage, and placed by the side of her bedridden husband. He, and also the daughter who resided with them, took the malady. All the three died within two days. Only one other case occurred in the village of Tockwith, and it was not a fatal case."

The mother appears to have been infected by Mrs. Barnes while she was taking care of her. She brought the disease back to her home village where the disease was rare, and infected her husband and daughter (the sister of Mrs. Barnes). So the story ends. In the course of few days, cholera during the epidemic of 1831-32 robbed Mrs. Barnes of her husband, caring mother, father and sister, all brought on by a package that arrived on Christmas day.

Sources:

Colton GW. Map of England and Wale, Colton's Atlas of the World, 1856.

Leech, John (illustrator). Mr Fezziwig's Ball, in A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens, 1843.

Map of England and Wales Divided into Counties, Parliamentary Divisions and Dioceses. Shewing the Principal Roads, Railways, Rivers and Canals, Published by S. Lewis and Co., London. c1840.

Snow J. On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, 1855.

1848-49 EPIDEMIC

STORY 2: Early Cholera Cases in London (1848)

Fifteen cholera cases were described by Snow at the start of the 1848-49 epidemic. They were mentioned both in his 1857 article on the Abbey-Row outbreak and in his 1855 book, Communication of Cholera.

In the early 1800's London households were using cesspools at their homes to contain liquid waste and sewage. Usually the cesspools were made of brick, about six feet deep and four feet wide, placed under the privy in gardens or basements, or as containers under the front curb. By 1856, there were around 200,000 cesspits and 360 sewers in the city. Nuisance laws were passed in the 1840s to help address the various sanitation issues. Included was the establishment of the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers (MCS) in 1848, coupled with the Public Health Act in the same year. Soon thereafter, MCS mandated that cesspools be closed and that house drains be connected to the sewers.

A decade later, The Lancet reflected on how these sanitation actions had ended up polluting the River Thames: "The concentrated refuse of some millions of people are daily poured into the Thames in the immediate vicinity of their habitations. This refuse consists of waste and effete material of all kinds, including solid excrements and urine, compounded of a variety of noxious and hurtful substances. Again, this refuse, bad and offensive as it is originally, is not poured at once and directly into the Thames, but is first discharged into the sewers, where it accumulates, festering and rotting, and by its decomposition gives rise to the generation of various additional hurtful or poisonous compounds; and it is in this foul state that it is conveyed to the river, where, mingled with water, it undergoes further corruption."

Source: Analytical Sanitary Commission, “Report upon the Present Condition of the Thames,” Lancet 75 (1819), 1858, pp. 43–45.

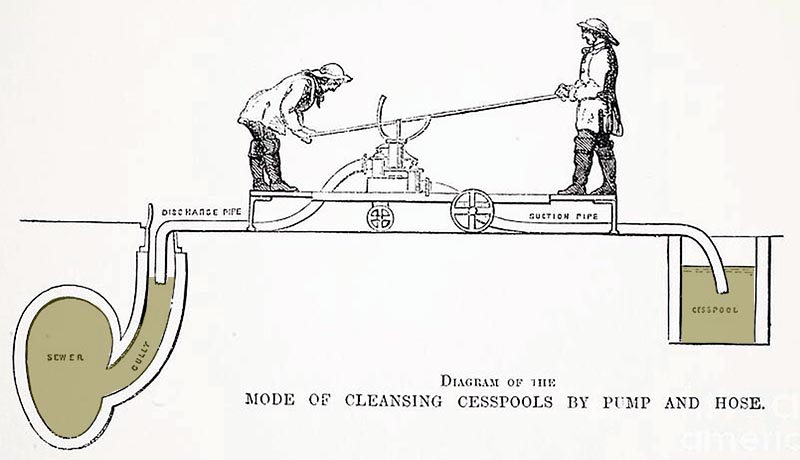

Special teams were established to help transfer human waste from cesspools to sewage lines, then flowing on to the River Thames where early cholera cases continued to arise.

Source: Mayhew, Henry. London Labour and the Urban Poor, London: G. Newbold, 1851.

CASE 1 (onset Sept. 22, 1848; death Sept. 22)

- Snow, John. Communication of Cholera, 1855, p. 66

CASE 2 (onset Sept. 30, 1848)

"Now the next case of cholera, in London, occurred in the very room in which the above patient died. A man named Blenkinsopp came to lodge in the same room. He was attacked with cholera on the 30th September, and was attended by Mr. Russell of Thornton Street, Horsleydown, who had attended John Harnold [the first case]. Mr. Russell informed me that, in the case of Blenkinsopp, there were rice water evacuations; and, amongst other decided symptoms of cholera, complete suppression of urine from Saturday till Tuesday morning; and after this the patient had consecutive fever. Mr. Russell had seen a great deal of cholera in 1832, and considered this a genuine case of the disease; and the history of it leaves no room for doubt."

- Snow, John. Communication of Cholera, 1855, p. 66

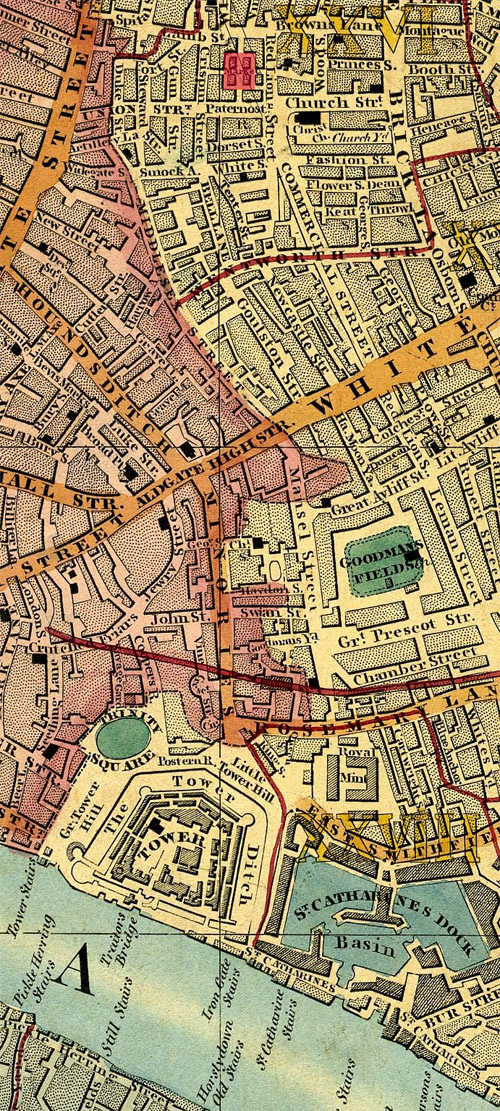

Cases 1-2, 1846 Map

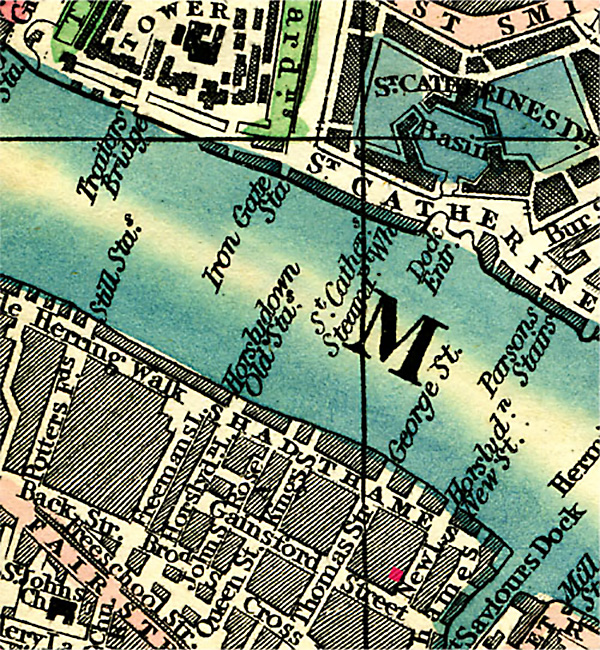

The first two cholera cases in 1848 occurred in the same room but a week apart at No. 8, New Lane (red dot) near Gainsford Street in the community of Horsleydown, across the River Thames from the Tower of London.

CASE 3 (onset Sept. 30, 1848; death Oct. 1, 1848)

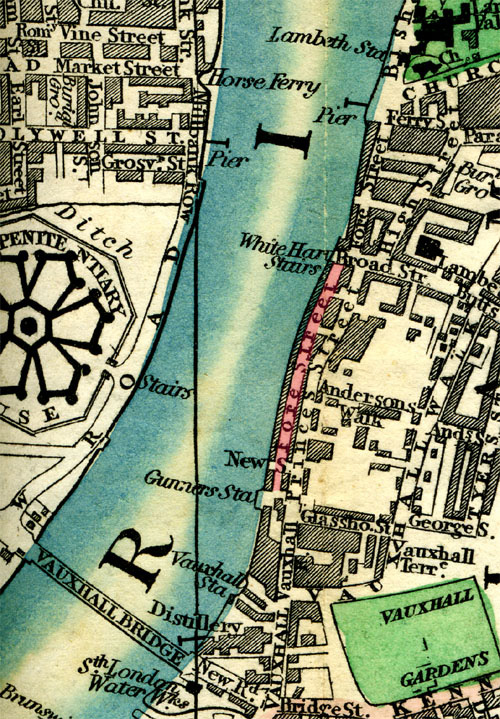

"In the evening of the day on which the second case occurred in Horsleydown, a man was taken ill in Lower Fore Street, Lambeth, and died on the following morning.

"Now, the people in Lower Fore Street, Lambeth, obtained their water by dipping a pail into the Thames, there being no other supply in the street."

- Snow, John.Communication of Cholera, 1855, p. 66

The upper section of Fore street extents south from Church Street, along the River Thames. Lower Fore street (in red), where the third cholera case occurred in 1848, extends south from Broad Street. The street lies directly across the River Thames from the Millbank Penitentiary.

Case 3, 1846 Map

Source: G.F. Cruchley. Cruchley's New Plan of London improved to 1846, Cruchley Map Seller and Publisher, 1846.

CASES 4-10 (onset Sept. 30-?, 1848)

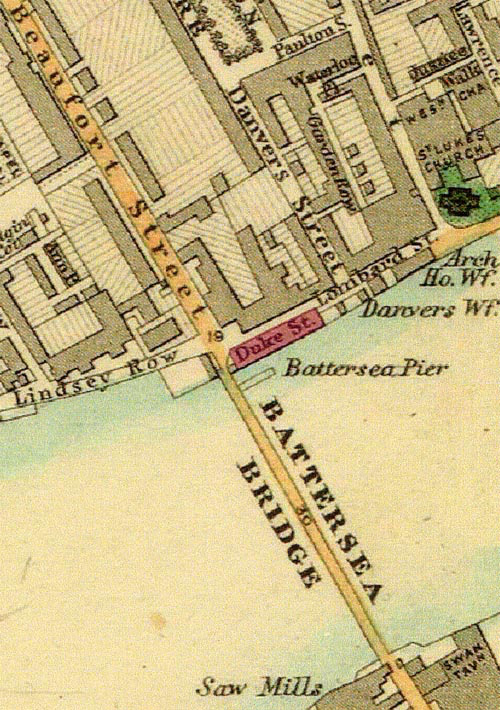

"At the same time that this case occurred in Lambeth, the first of a series of cases occurred in White Hart Court, Duke Street, Chelsea, near the river."

"In White Hart Court, Chelsea, the inhabitants obtained water for all purposes in a similar way [i.e., dipping a pail into the Thames]. A well was afterwards sunk in the court; but at the time these cases occurred the people had no other means of obtaining water, as I ascertained by inquiry on the spot."

- Snow, John. Communication of Cholera, 1855, p. 66-67

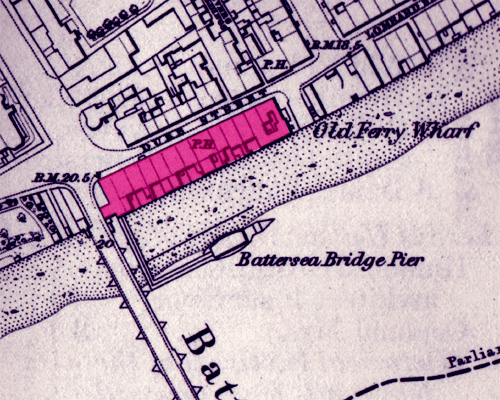

Cholera cases 4-10 in 1848 occurred in White Hart Court (in red), shown below left in 1818 as situated directly by the River Thames, followed by three other maps. The Court inhabitants obtained drinking water from buckets dipped into the often-polluted River Thames.

Cases 4-10 continued...

Cases 4-10, 1818 Map

Source: Cary, J. Cary's New and Accurate Plan of London and Westminster, the Borough of Southwark and parts adjacent, viz. Kensington, Chelsea, Islington, Hackney, Walworth, Newington, etc., Printed for John Cary, Engraver and Map Seller, No. 181, near Norfolk Street, Strand, London, 1818.

Cases 4-10, 1850 map

White Hart Court (in red) where cholera cases 4-10 occurred is not cited on Cross' 1850 map, but lies south of Duke Street and east of the Battersea Bridge. The inhabitants' main source of drinking water was the River Thames.

Source: Cross, J. Cross's New Plan Of London 1850, J. Cross, 18, Holborn Hill, opposite Furnivals Inn, January 1, 1850.

Cases 4-10, 1862 map

In 1862, White Hart Court (in red) was again incorrectly labeled "Duke Street" instead of White Hart Court. Duke Street is the short segment of the road between Beaufort Street and Lombard Street, just above the incorrectly named "Duke Street."

Source: Stanford's Library Map of London and its Suburbs. Published by Edward Stanford, 6, Charing Cross, London, February 15, 1862.

Cases 4-10, 1865 map

Finally, in the government's 1865 Ordnance Survey map (seven year after the death of John Snow), White Hart Court is clearly shown (in red), just south of small-lettered Duke Street, both adjacent to the Battersea Bridge.

Source: Old Ordnance Survey Maps -- Chelsea, 1865.

CASE 11 (onset Oct. 1, 1848)

"A day or two afterwards, there was a case at 3, Harp Court, Fleet Street."

"The inhabitants of Harp Court, Fleet Street, were in the habit, at that time, of procuring water from St. Bride's pump, which was afterwards closed on the representation of Mr. Hutchinson, surgeon, of Farringdon Street, in consequence of its having been found that the well had a communication with the Fleet Ditch sewer, up which the tide flows from the Thames."

- Snow, John. Communication of Cholera, 1855, p. 67

Case 11 continued...

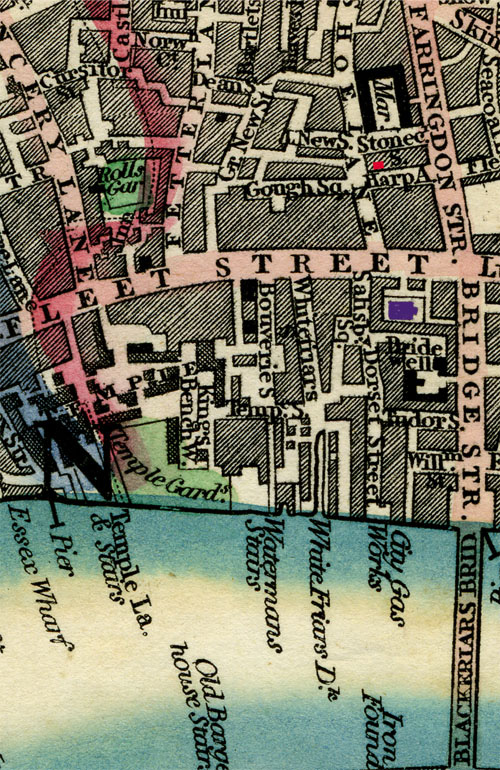

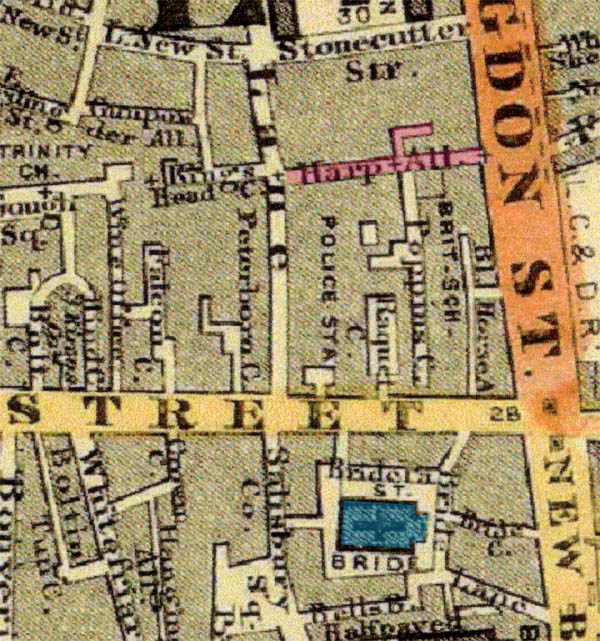

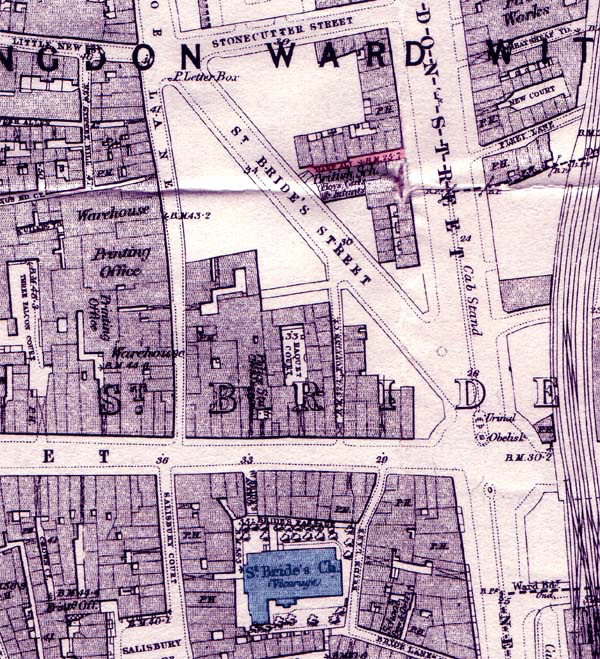

Harp Court (actually Harp Alley) is near St. Bride's church but north of Fleet Street, as seen in Cruchley's map of 1846 and Stanford's 1862 map. By 1873, the area was altered with new street construction.

As seen below in the 1846 map, the case occurred at 3, Harp Alley (in red). The small street, located a short distance north of Fleet Street, is likely synonymous with "Harp Court" as written by Dr. Snow. Just south of Fleet Street is St. Bride's Church (in purple) near where the St. Bride's pump that Dr. Hutchinson had closed was located. The "Fleet Ditch sewer" Dr. Snow referred to runs underneath Farringdon Street and accesses the River Thames at the base of Blackfriars Bridge.

Case 11, 1846 map

Source: G.F. Cruchley. Cruchley's New Plan of London improved to 1846, Cruchley Map Seller and Publisher, 1846.

In the 1862 map below, Harp Court (in red, listed as Harp Alley) is seen north of Fleet Street and south of Stonecutter Street. St. Bride's church (in blue), near where the pump was probably located, is south of Fleet Street. Farringdon Street, where Mr. Hutchinson lived, is to the right (in orange).

Case 11, 1862 map

Source: Stanford's Library Map of London and its Suburbs. Published by Edward Stanford, 6, Charing Cross, London, February 15, 1862.

Between 1862 and 1873, St. Bride's Street was built, altering Harp Court (the remainder is seen in red) where the cholera cases occurred. St. Bride's church (in blue) is south of Fleet Street. The St. Bride's pump was located, perhaps, near the urinal and obelisk at the center right.

Case 11, 1873 map

Source: Old Ordnance Survey Maps -- Holborn, The City and The Strand, 1873.

CASE 12 (onset Oct. 2, 1848)

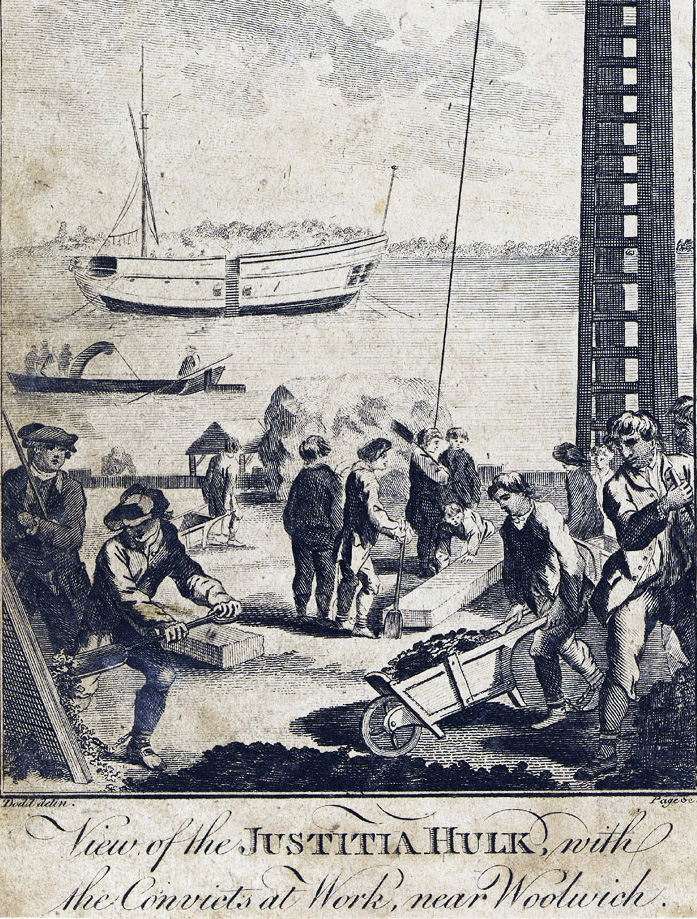

The next case occurred on October 2nd, on board the hulk Justitia, lying off Woolwich.

"I was informed by Mr. Dabbs, that the hulk Justitia was supplied with spring-water from the Woolwich Arsenal; but it is not improbable that water was occasionally taken from the Thames alongside, as was constantly the practice in some of the other hulks, and amongst the shipping generally."

- Snow, John. Communication of Cholera, 1855, p. 67

The term "hulk" in hulk Justitia indicates the boat was used as a floating prison, used to alleviate overcrowding in regular land-based prisons. Life on board a prison hulk was notoriously difficult, with prisoners living in cramped, unhygienic, and disease-ridden settings. During daytime, the prisoners were typically put to work in hard labor, dredging harbors or working in places like Woolwich Arsenal.

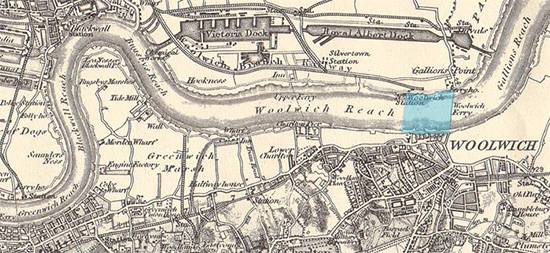

Woolwich is down river from London. The location where the Justinia was docked is seen below in the Ordnance Survey map of 1844. The ship is docked by the Woolwich Arsenal in the blue region of the River Thames. The Isle of Dogs is seen to the left.

Source: Ordnance Survey of Brentwood and East London, engraved at the Ordnance Map Office, Southhampton. Published by Colonel Colby, July 12, 1844, levels revised in 1884, railways inserted to November 1892.

The Woolwich Arsenal in 1885 was described as lying "by the side of the river like a low line of sheds, very bare and poor-looking, very disappointing, very unlike what one would expect the chief arsenal of England to be."

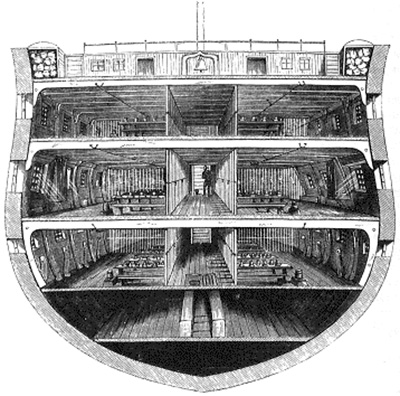

Typical sectional view of a "hulk" ship.

Case 12 continued...

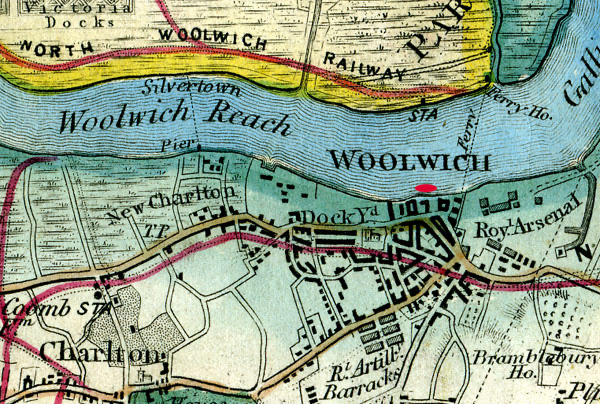

Case 12, 1872 map

As seen in the 1872 map below, Justitia (in red) was docked in the River Thames at Woolwich, close to the Royal Arsenal (termed the "Woolwich Arsenal" by Dr. Snow). The boat was located downstream from London, in a location where river water likely was polluted. Case 12 may have dipped a bucket into the River Thames for washing and drinking.

Source: Wyld, J. A New Map of the Country Twenty-five Miles Round London. Published by James Wyld, Geographer to the Queen, Charing Cross East, London, 1872.

CASE 13 (onset Oct. 3-4, 1848)

The thirteenth case arose on Lower Fore Street which was described earlier.

"...and the next to this in Lower Fore Street, Lambeth [see case 3 above], three doors from where a previous case had occurred."

- Snow, John. Communication of Cholera, 1855, p. 66

Snow concludes, "The first thirteen cases were all situated in the localities just mentioned;"

- Snow, John. Communication of Cholera, 1855, p. 66-67

CASES 14-15 (onset Oct. 5, 1848)

"...and on October 5th there were two cases in Spitalfields."

- Snow, John. Communication of Cholera, 1855, p. 67

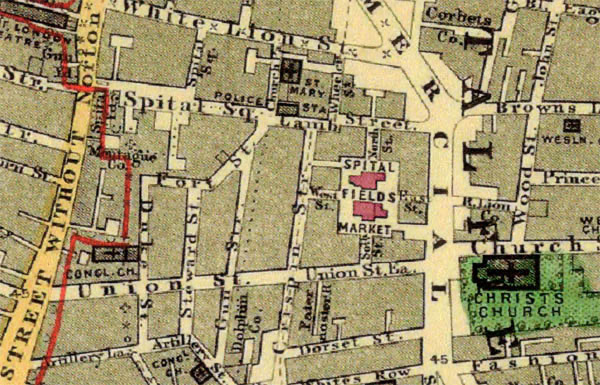

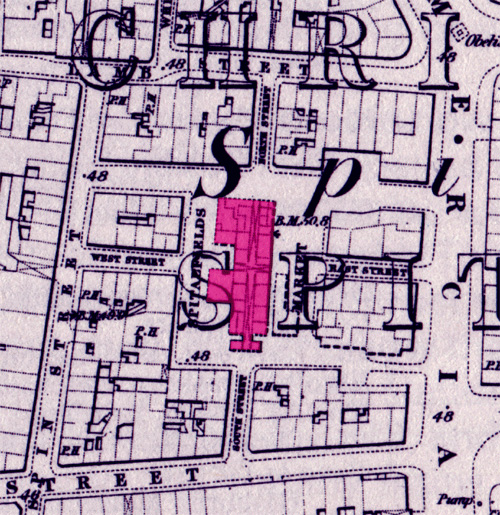

Spitalfields was a rapidly expanding area of London north of the River Thames. The region was was occupied primarily by immigrants, and featured many dilapidated homes and common lodging houses. The poor housing was cleared away in the middle 1800s to make way for commercial development. Snow did not give an address for the two Spitalfields cases but I will assume they were located near the Spitalfields Market at the center of the area.

Cases 14-15 continued...

The 1850, 1862 and 1873 maps show additional details of the Spitalfields area.

Source: Cross, J. Cross's New Plan Of London 1850, J. Cross, 18, Holborn Hill, opposite Furnivals Inn, January 1, 1850.

The last two cholera cases described by John Snow in the 1848 outbreak occurred somewhere in Spitalfields, perhaps near Spitalfields Market (in red, all 3 maps ).

Source: Stanford's Library Map of London and its Suburbs. Published by Edward Stanford, 6, Charing Cross, London, February 15, 1862.

Spitalfields Market (in red) is in Spitalfields, the community where in 1848 cholera cases 14 and 15 occurred, as presented by Dr. Snow. The market is surrounded clockwise by Lamb Street, Commercial Street, Brushfield Street (formerly Union), and Crispin Street.

Source: Old Ordnance Survey Maps -- Whitechapel, Spitalfields and The Bank, 1873.

The Spitalfields Market was very successtful at servicing the people in the area. In the late 1600's the Huguenots fled France and brought their silk weaving skills to Spitalfields, adding grand houses to the region. By the mid-1700s Irish weavers appeared, following the decline in the Irish linen industry. The Irish were followed by East European Jews escaping the Polish pogroms and harsh conditions in Russia; as well as entrepreneurial Jews from the Netherlands. From the 1880s on, Spitalfields was overwhelmingly Jewish. The Spitafields Market in 1841 is shown below.

Source: Anonymous. Spitalfields Market in London, 1841

More on 1848-49 epidemic cases is in the third section and part 3 of John Snow's bookCommunication of Cholera, 1855.

Sources:

Angus, Ian. Cesspools, Sewage, and Social Murder. Monthly Rview 70(3), July-August 2018.

Halliday S. The Great Stink of London, 1999.

History of Spitalfields Market (https://www.spitalfields.co.uk/spitalfields-history/), 2025.

Snow, John. Communication of Cholera, 1855.

Weinreb B, Hibbert C (eds). The London Encyclopaedia, 1993.

1848-49 EPIDEMIC CONTINUED...

Source: Spielmann MH. Chapter VII, "Cartoons — Cartoonists and Their Work." The History of "Punch". London: Cassell, 1895.

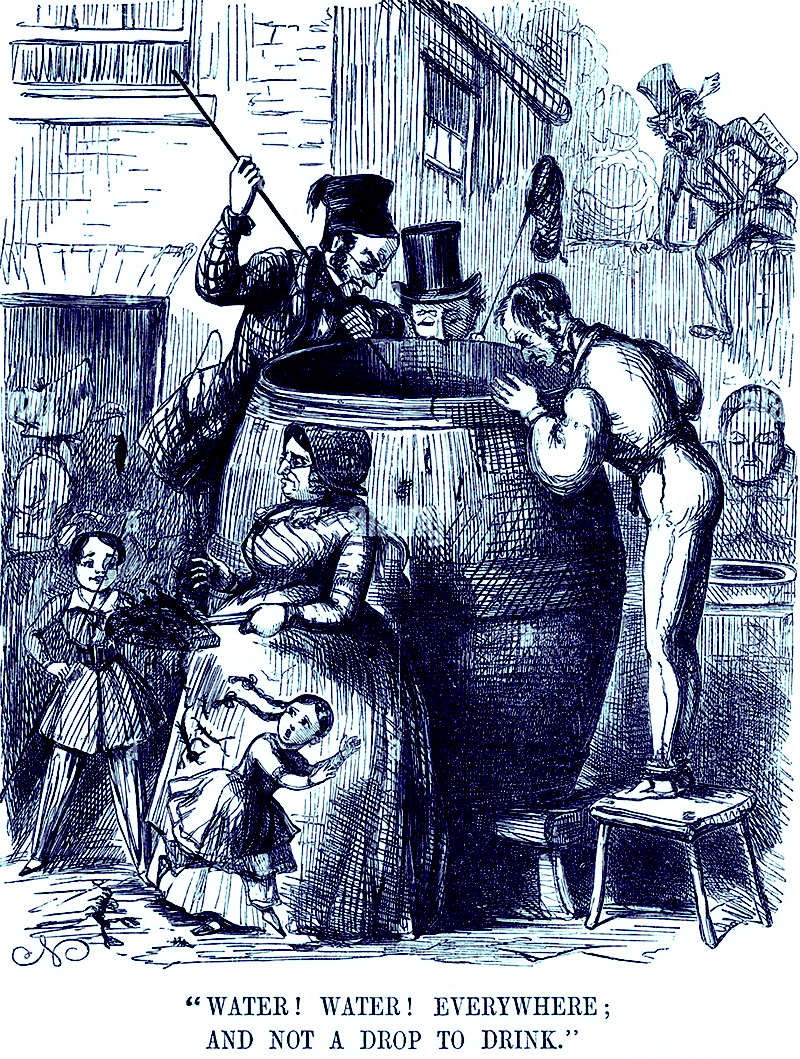

In 1849, illustrator William Newman (1817-1870) often played second fiddle to renowned caricaturist John Leech, a major contributor to Punch. Yet for the October 13, 1849 issue of Punch, Leech had a serious boating accident, while holidaying with Charles Dickens on the Isle of Wight. Newman received the assignment, during a time when Dr. John Snow and others were talking about the potential hazzards of getting cholera from drinking water, generating much public anxiety.

Thinking back to his childhood, Newman remembered an an old poem, "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner," written by Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1798 with a verse:

Water, water, every where,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, every where,

Nor any drop to drink.

Newmann changed "nor any drop to drink" to "not a drop to drink" and was off to the races.

A year earlier, he had done a cartoon for Punch that had a similar theme

STORY 3: Plaque of the Lambeth Cholera Epidemic (1848-49)

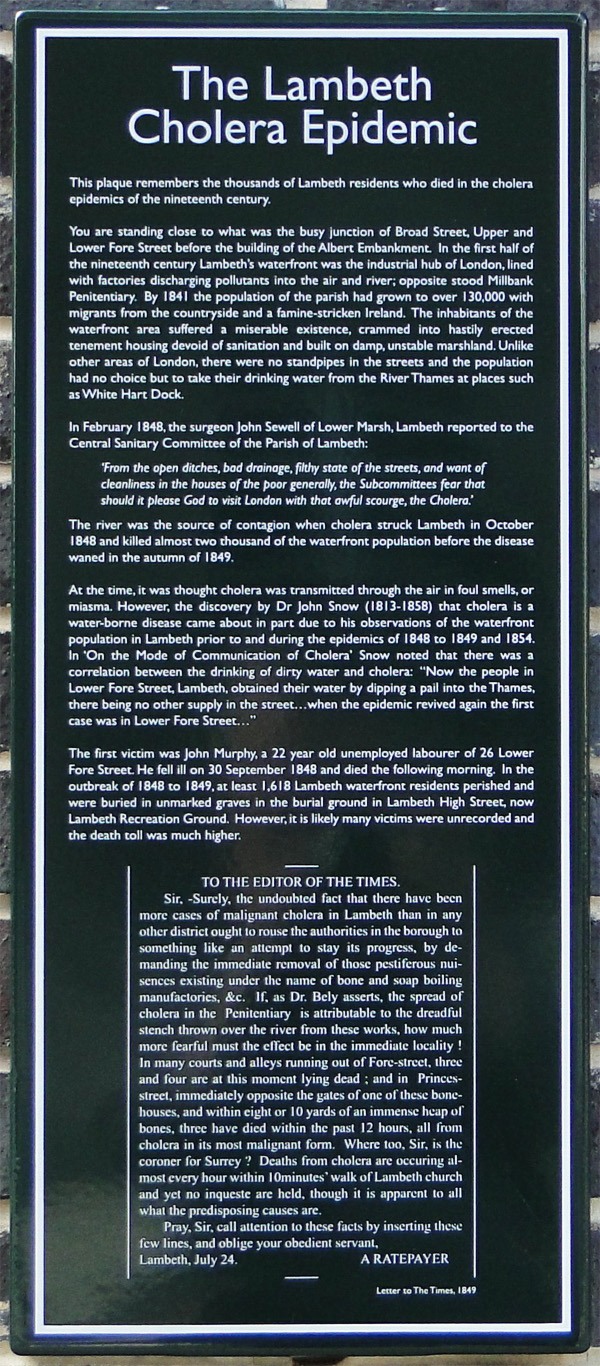

A plaque was placed in 2010 near London's River Thames remembering the cholera epidemic of 1848-49. The narrative was written by Amanda J. Thomas, author of a well-regarded book, The Lambeth Cholera Epidemic of 1848-49.

In addition to the Lambeth scourge, the plaque mentions the work of Dr. John Snow, who wrote of the Lambeth cases in part three of his 1855 book, On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, 1855.

TEXT OF PLAQUE

The Lambeth cholera epidemic

This plaque remembers the thousands of Lambeth residents who died in the cholera epidemics of the nineteenth century.

You are standing close to what was the busy junction of Broad Street, Upper and Lower Fore Street before the building of the Albert Embankment. In the first half of the nineteenth century Lambeth's waterfront was the industrial hub of London, lined with factories discharging pollutants into the air and river; opposite stood Millbank Penitentiary. By 1841 the population of the parish had grown to over 130,000 with migrants from the countryside and a famine-stricken Ireland. The inhabitants of the waterfront area suffered a miserable existence, crammed into hastily erected tenement housing devoid of sanitation and built on damp, unstable marshland. Unlike other areas of London, there were no standpipes in the streets and the population had no choice but to take their drinking water from the River Thames at places such as White Hart Dock.

In February 1848, the surgeon John Sewell of Lower Marsh, Lambeth reported to the Central Sanitary Committee of the Parish of Lambeth:

'From the open ditches, bad drainage, filthy state of the streets, and want of cleanliness in the houses of the poor generally, the Subcommittees fear that should it please God to visit London with that awful scourge, the Cholera.'

The river was the source of contagion when cholera struck Lambeth in October 1848 and killed almost two thousand of the waterfront population before the disease waned in the autumn of 1849.

At the time, it was thought cholera was transmitted through the air in foul smells, or miasma. However, the discovery by Dr John Snow (1813 - 1858) that cholera is a water-borne disease came about in part due to his observations of the waterfront population in Lambeth prior to and during the epidemics of 1848 to 1879 and 1854. In 'On the Mode of Communication of Cholera' Snow noted that there was a correlation between the drinking of dirty water and cholera: "Now the people in Lower Fore Street, Lambeth obtained their water by dipping a pail into the Thames, there being no other supply in the street… when the epidemic revived again the first case was in Lower Fore Street…"

The first victim was John Murphy, a 22 year old unemployed labourer of 26 Lower Fore Street. He fell ill on 30 September 1848 and died the following morning. In the outbreak of 1848 to 1849, at least 1,618 Lambeth waterfront residents perished and were buried in unmarked graves in the burial ground in Lambeth High Street, now Lambeth Recreation Ground. However, it is likely many victims were unrecorded and the death toll was much higher.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE TIMES

Sir, -Surely the undoubted fact that there have been more cases of malignant cholera in Lambeth than in any other district ought to rouse the authorities in the borough to something like an attempt to stay its progress, by demanding the immediate removal of those pestiferous nuisances existing under the name of bone and soap boiling manufactories, etc. If, as Dr Bely asserts, the spread of cholera in the Penitentiary is attributable to the dreadful stench thrown over the river from these works, how much more fearful must the effect be in the immediate locality! In many courts and alleys running out of Fore-street, three and four are at this moment lying dead; and in Princes-street, immediately opposite the gates of one of these bone-houses, and within eight or 10 yards of an immense heap of bones, three have died within the past 12 hours, all from cholera in its most malignant form. Where too, Sir, is the coroner for Surrey? Deaths from cholera are occurring almost every hour within 10 minutes’ walk of Lambeth church and yet no inquests are held though it is apparent to all what the predisposing causes are.

Pray, Sir, call attention to these facts by inserting these few lines, and oblige your obedient servant,

Lambeth, July 24. A Ratepayer

Letter to The Times, 1849.

Where the New Plaque would have been in 1846 map of London

In an 1846 map of London, the plaque would have been located at the base of Broad Street by White Hart Stairs, a few blocks South of the Lambeth Palace. Notice that White Hart Stairs is the dividing point between two sections of Fore Street.

It was at 26 Lower Fore Street (red dot) that the first cholera case in the Lambeth area, 22-year old John Murphy, showed symptoms on September 30, 1848 before dying the next day (see plaque above for details).

The Third London Cholera Case of 1848

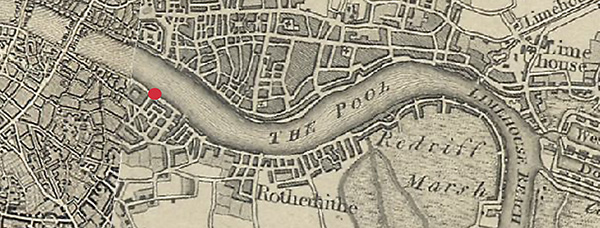

While John Murphy is now remembered in the new plaque for his cholera death in the Lambeth neighborhood, the 1848 cholera epidemic actually started elsewhere in London. Murphy was the third cholera case in London during the 1848 epidemic. As John Snow described in his 1855 book, "The first case of decided Asiatic cholera in London, in the autumn of 1848, was that of a seaman named John Harnold, who had newly arrived by the Elbe steamer from Hamburgh [Germany], where the disease was prevailing. He left the vessel, and went to live at No. 8, New Lane, Gainsford Street, Horsleydown. He was seized with cholera on the 22nd of September, and died in a few hours."

Snow went on to state, "Dr. Parkes, who made an inquiry into the early cases of cholera, on behalf of the then Board of Health, considered this as the first undoubted case of cholera."

The second case of cholera in London in 1848, occurred in the same room in which John Harnold, the above patient, had died.

The third case, identified in the new plaque as John Murphy was described by Snow, but without a name, "In the evening of the day on which the second case occurred in Horsleydown, a man was taken ill in Lower Fore Street, Lambeth, and died on the following morning." Snow continued to write, "Now, the people in Lower Fore Street, Lambeth, obtained their water by dipping a pail into the Thames, there being no other supply in the street." It is likely that this practice brought the cholera organism from the River Thames to John Murphy, and lead to his demise.

Continuation of Cholera Epidemic in Lambeth in 1849

More on cholera in Lambeth in 1849 was written by Snow in his 1855 book, describing his personal field observations. "When the epidemic revived again in the summer of 1849, the first case in the sub-district 'Lambeth; Church, 1st part,' was in Lower Fore Street, on June 27th; and on the commencement of the epidemic of the present year, the first case of cholera in any part of Lambeth, and one of the earliest in London, occurred at 52, Upper Fore Street, where also the people had no water except what they obtained from the Thames with a pail, as I ascertained by calling at the house."

Snow went on to write, "Many of the earlier cases this year occurred in persons employed amongst the shipping in the river, and the earliest cases in Wandswroth and Battersea have generally been amongst persons getting water direct from the Thames, or from streams up which the Thames flows with the tide. It is quite in accordance with what might be expected from the propagation of cholera through the medium of the Thames water, that it should generally affect those who draw it directly from the river somewhat sooner than those who receive it by the more circuitous route of the pipes of a water company."

Location in 2011 of The New Plaque

The new Lambeth cholera plaque is located near the east bank of the RiverThames, and is shown with a red circle. The Lambeth Palace is off a few blocks to the North (i.e., left). The cross streets by the location of the new Cholera Plaque are Albert Embankment and Black Prince Road. The large building facing the river just above the words "Albert Embankment" is the London Fire Brigade Headquarters.

Sources:

Prockter A. Photographs and description of plaque location, 2011.

Snow J. On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, 1855.

Thomas AJ. The Lambeth Cholera Epidemic of 1848-1849 -- The Setting, Causes, Course and Aftermath of an Epidemic in London. McFarland and Co, North Carolina, USA 2010.

Thomas AJ. Commissioned author of The Lambeth Cholera Epidemic plaque, personal communication, 2014.

The next photo is taken on Black Prince Road by the side of the London Fire Brigate Headquarters looking South (i.e., right). The plaque is located on the brick post at the right. Funding for the plaque was provided by Planning Gain, a financial requirement of developers and builders to put money into cleaning up the walls of the dock, adding artistic improvement to the waterfront region, and promoting awareness of London's history.

Following the 1848-49 epidemic, John Snow in 1849 published a pamphlet of his thoughts in On the Mode of Communication of Cholera. It preceded by six years his more complete book of the same name in 1855. The pamphlet had a limited impact, at least with the broader public since the miasma theory of "bad air" still prevailed, as did an observed link between overcrowding among the poor and the spread of cholera.

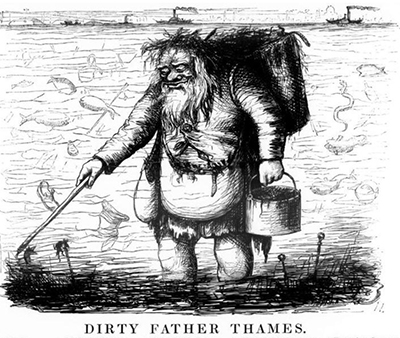

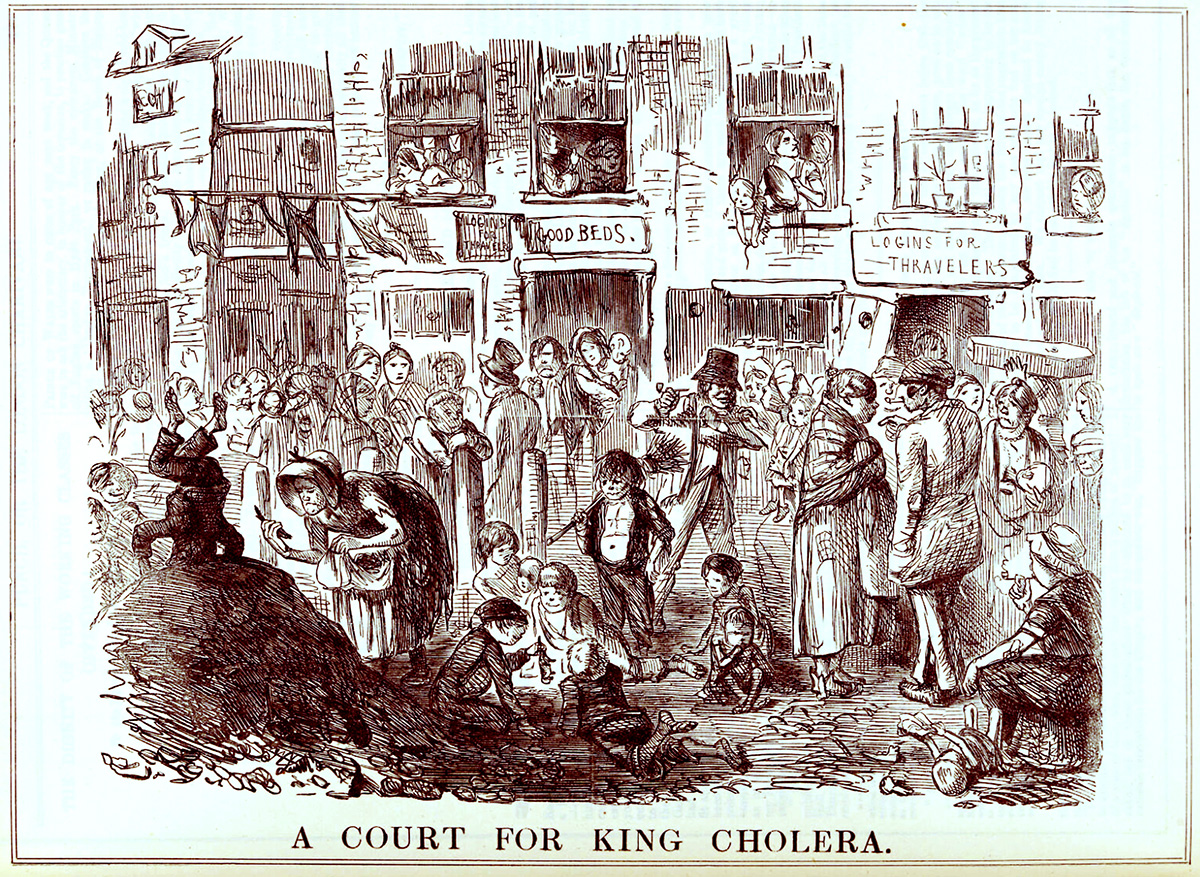

Capturing public feeling at the time was John Leech's 1852 caricature in Punch magazine. "King Cholera's Court" was bereft with crowded housing, and dirty, cramped streets where despondent women and seedy looking men experienced the wrath of powerful "King Cholera," with only the smiles of a few children showing innocent hope, one doing a handstand on a garbage heap. Alas there was no visualization by Leech of Snow's theory on contaminated water, offering a suggestion of public health empowerment.

Source: Leech, John. A Court for King Cholera, Punch 25 September 1852, p. 139.

1853-54 EPIDEMIC

STORY 4: Abbey-Row Pump Well Outbreak (1857)

Source: Former site Abbey Mill, Channelsea River (Channelsea Island) in East London, Photo by Gordon Joly, Jan. 2, 2017.

In 1857 John Snow wrote about a small cholera outbreak, starting on September 29, 1857, that he investigated in east London near West Ham. Snow explains in the narration how the cholera organism (not yet identified as Vibrio cholerae) likely got into the pump well from an infected person and then via water spread to the other pump-users in the area. He also opines that transmission may have been reduced when people refused to drink foul-smelling water.

In modern times, this would be a typical outbreak investigation done by an epidemiologist, working for the local or national government. But Snow was different. Epidemiology had not been formalized as a profession. At that time it was more of a hobby, driven by intellectual curiosity. The income from Snow's clinical practice and as an anesthetist allowed him to do the epidemiological work on the side. Fortunately he had an excellent reputation and good working personality, so was able to get the cooperation of a local physician.

Sources: Snow, John. Med. Times and Gazette, n. s. vol. 15, Oct. 24, 1857, pp. 417-419; and Snow, John. British Medical Journal 2, 7 November 1857, pp.934-35 [Letter to Ed.].

On the Outbreak of Cholera at Abbey-row, West Ham

and On the origin of the recent outbreak of cholera at West Ham

By John Snow, M.D.

On seeing the notice in the Medical Times and Gazette of the 17th instant of the outbreak of cholera at West Ham, I called on Dr. Elliott, of Stratford, who was kind enough to take me to the place where the outbreak occurred, and to inform me of the various particulars connected with it. I also made some inquiries of the inhabitants, and the proprietor of the greater part of the property was good enough to give me some information respecting the drainage. The row of small houses in which the outbreak has occurred is situated, as was stated in the Medical Times and Gazette, about a hundred yards from the River Lea, and about two miles from the Thames.

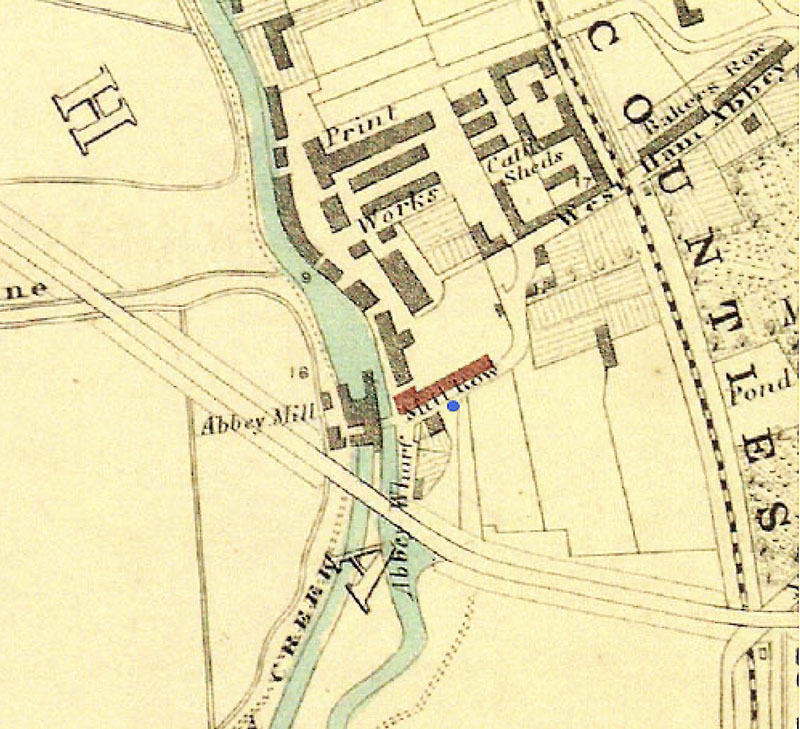

The location of West Ham in relation to Soho Square nearby to his home, is shown below in Reynolds's 1862 map (Soho Square, red dot upper left; Isle of Dogs, red dot lower right). To the right in an 1841 map is the row by the Abbey Mill area, north of the Isle of Dogs, where the outbreak took place (red tinged square). The green dot is where the young boy from Bromley lived who Snow later wrote about in a follow-up story.

Source: Reynolds, J., Reynolds's Map of London and Visitors Guide, 1862.

Source: Davies, BR . Map of London, 1841 in Barker F and Jackson P. The History of London Maps, Barrie and Jenkins, London, 1990.

The cholera outbreak which John Snow first described took place on Abbey-row (shown in red), labeled in the 1862 map as "Shift Row," across the eastern branch of the Lea River from a flour mill. The location of the shallow pump well which Snow associated with cholera, is shown in blue. The pump supplied water for the residents of Abbey-row, persons living in the Abbey flour mill, and several other households near the mill by the river.

Source: Stanford's Library Map of London and its Suburbs. Published by Edward Stanford, 6, Charing Cross, London, February 15, 1862.

The row consists of eighteen dwellings: sixteen of these contain but two rooms, one over the other, and a small back kitchen; at the north-east end of the row, which is the farthest from the River Lea, is a house with four rooms, and at the opposite end of the row is a still larger house, occupied by the proprietor of the large flour-mills, a few paces further on, situated on the banks of the Lea, and partly overhanging it.

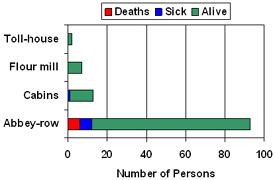

The water which the inhabitants of Abbey-row used for every purpose was that of a pump-well near the middle of the row, and across the road. It is a shallow pump-well of not more than twenty feet deep, in the opinion of the proprietor. A few years ago, before this well was sunk, the inhabitants of the place had no other water than that of the River Lea. Besides Abbey-row, the above pump supplied a dwelling in the above-mentioned flour-mill, a small dwelling just beyond the mill, and across the bridge, called the toll-house, and four very small cabins of one room a little way--perhaps thirty yards--from the mill, and situated under the bank of the Lea, and much below its level when the tide is up. When standing on the bank of the Lea, just above the water’s edge, one is almost on a level with the roofs of these cabins.

The number of inhabitants in the dwellings having the water supply of the above-mentioned pump was, at the beginning of the epidemic, 115, and they were distributed as follow; 93 in Abbey-row, 7 in the flour-mill, 2 in the small toll-house, and 13 in the four little cabins. The cases of cholera at West Ham have been confined to this population, with one exception to be mentioned afterwards. Out of the above-mentioned 115 persons, 6 died of cholera between the 3rd and 13th of the present month, being rather over 5 per cent.

These 6 fatal cases indeed all occurred in Abbey-row, having but 93 inhabitants. Dr. Elliott informed me that there were also 6 or 7 very severe and decided cases of cholera which ended, or were in progress, of recovery. Cases which proceeded no further than diarrhea, but which form a part of the same outbreak were numerous: by inquiry from house to house I found that, from September 29th, when the first case (not fatal) occurred, till October 16th, there had been 19 cases of illness with bowel complaint, sufficiently severe to require medical treatment, in addition to the fatal cases; so that above one-fifth of the inhabitants were more or less implicated in the epidemic. As some families were from home, or had removed, there might have been slight cases of illness that I did not hear of. I was only informed of one case of illness amongst the 13 inhabitants of the four little cabins mentioned above, so that they seem to have escaped rather better than the other inhabitants having the same drinking water. These cabins are inhabited by the families of labourers. The inhabitants of Abbey-row are clean looking and apparently industrious people. The men are chiefly employed in a large silk factory close by. The single case of cholera which occurred to any one at West Ham, or even near it, so far as is known, happened to the sister of a licensed victualler (a British term for innkeeper), living opposite to Abbey-row, and assisting in the business. The public house was supplied by a separate pump-well, on the premises. The public-house is distant from Abbey-row only the width of the road; and I may mention that, except where this public-house obstructs it the view extends from the front of the dwellings in Abbey-row across the marshes to the shipping at Blackwall and Greenwich.

The water of the pump which supplied the houses described above, was very impure, letting fall a copious deposit of dirty organic matter on standing. The nature of this deposit leaves no doubt on any one's mind that it proceeds from the sewer and drains which pass within a few feet of the well: but whether the leakage is by percolation, or by a direct opening, has not yet been determined. There is a ditch or sewer which passes behind the pump-well, and within a few feet of it. The ditch is now covered at this spot, but Mr. Kayess of West Ham Abbey showed me a plan of it. This ditch or sewer flows into the River Lea when the tide permits, but at other times the water from the Lea flows back up the ditch, as may be observed; for it is still opened in a great part of its course between the river Lea and the pump. The drains from Abbey-row pass under the road, and pass very near to this pump-well, before entering the above-mentioned tidal ditch. The five houses in Abbey-row nearest to the house of the proprietor of the flour-mill belong to that gentleman; they are each provided with a privy over a cesspool; some, at least, of these privies have an overflow drain, which pass under the house and road to reach the tidal sewer. The remaining twelve houses belong to Mr. Kayess, mentioned above, and the privies of the first eleven of these were converted about a year ago into water-closets, the water being however carried from the pump and thrown down.[a]

These closets communicate, by means of drain pipes, with a large covered cesspool at the back of the row, which receives also all the water used in the cottages; the overflow from the cesspool passes into the tidal sewer, by a drain which passes under the floor of the first house (that adjoining the last of the five belonging to the proprietor of the flour-mill) and then passes under the road and near to the pump-well. The impurity of the water of this pump-well was a chronic affair, and therefore, as mere impurity, would not account for the remarkably sudden and circumscribed outbreak of cholera which has occurred around it. Moreover, mere impurity in the water was never known to cause, or even aggravate, cholera. In all the sudden outbreaks of cholera which I have been able to connect with impure water, and have related in previous volumes of this Journal, and the two Journals from which it sprung, there has always been either absolute proof or strong presumption that the evacuations of a cholera patient had entered the water. In the fearful outbreak of cholera near Golden-square, which I described in the Medical Times and Gazette in Sept. 1854, I could myself only bring forward statistical and other evidence of the effect of the water, not having the power to open the well and adjoining drains; but when this was done by the parish authorities, at the suggestion of the Rev. Henry Whitehead, six months afterwards, the pump-well which caused the outbreak was found to be the recipient of the overflow from a cesspool, into which the evacuations of a child ill of cholera had been emptied within three days before the great irruption of the disease.

At Abbey-row, the contamination of the pump-well, forming the sole water-supply of the place, by the drains and sewer, which carry away the overflow from the water-closets and privies of that row, explains the way in which the cholera was propagated to so great an extent on the spot, when once it was introduced. Many of the persons attacked had had no personal communication with any previous patient. Some cases of illness followed a day or two after a previous case in the same family, and in these instances it is probable that the morbid matter of cholera was swallowed in the more ordinary way, without the medium of the water. I ascertained that a great number of the persons attacked were in the habit of drinking the water cold: but, in addition to the opportunity of taking the disease when it is first introduced into a household without the intervention of the water, it must be acknowledged that water, even before being boiled, enters in so many ways into the preparation of articles of diet, that every one is liable to take it.

Cholera prevailed in Abbey-row in 1832, 1849, and 1854, but not to the same extent as in the present month.

The boy from Bromley

Following his publication of his article about the Abbey-Row outbreak, Snow was critiqued by the Editors of the British Medical Journey questioning facets of his article. In his response to the BMJ editors, he included a story about a 14-year old boy from the nearby town of Bromley (the green dot in the 1841 map above), who days before he had learned about from a medical colleague.

"The case connected with this outbreak, of which I was not previously aware, is one investigated by Dr. Ansell. At the time of the cases at West Ham, just beyond the borders of the metropolis, there happened in the whole of London just one case, which, by suddenly attacking a person in good health, and proving rapidly fatal, showed itself to be of the true Asiatic type. This case was that of a boy, aged 14, living at Bromley, about two miles from Abbey Row; he passed this place with his father, on October 7th, on their return from a long walk. He lagged behind, which attracted his father's attention, who looked back, and saw the boy drinking at the pump above alluded to. The boy was still quite well on the evening of the following lay, but at five o'clock in the morning of the 9th, he was seized “with diarrhœa, vomiting, great prostration, darkness of surface, thirst, loss of voice,” and he died in twenty hours."

The incubation period of cholera for the boy was probably from mid-afternoon on October 7th, say around 3 pm, when he drank water from the shallow pump well (marked with a blue dot in an earlier map), to 38 hours later (about a day and a half) when diarrhea and vomiting took hold.

Snow also addressed river flow and movement of cholera in his response to the critical BMJ editors: "I am ready to admit that the greater part of any impurity emptied into the River Thames might go straight up and down with the tide, and reach in a few days the salt water, which nobody can drink; but it is a fact that a part of the water of the Thames does flow up the River Lea, and a part of this also up the tidal ditch to Abbey Row, carrying with it more or less of every kind, of impurity which enters the Thames." Cholera, reiterated in his point to BMJ editors and readers, moves like such an impurity.

Back to Snow's original writings about the the Abby-Row outbreak.

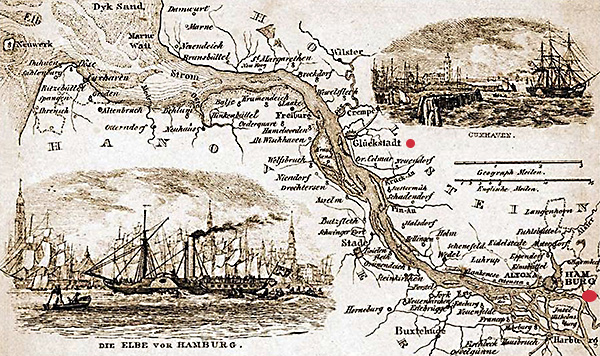

With regard to the introduction of the disease on the present occasion, the explanation I have to offer is somewhat circuitous, but is well supported by what has occurred in previous epidemics. In the Weekly Return of Births and Deaths for September 26 of the present year, the following death is recorded: "at Horselydown, on board the Lütcken, on 22nd September, a seaman, aged 27 years, cholera Asiatica (nineteen hours)." The following note is added - "The ship Lütcken arrived at Horselydown on the afternoon of the 21st instant from Harburgh (Hamburg); she had touched at Gluckstadt, and stopped there twenty hours, at which place cholera raged lately, and carried off five per cent, of the inhabitants. The deceased had not been ashore at Horselydown."

More on Germany connection, bringing cholera to Abbey-Row.

The harbors at Hamburg and Gluckstadt in Germany along the Elba River in 1860 are shown below (red dots).

Source: Pincerno, Niederelba, 1860.

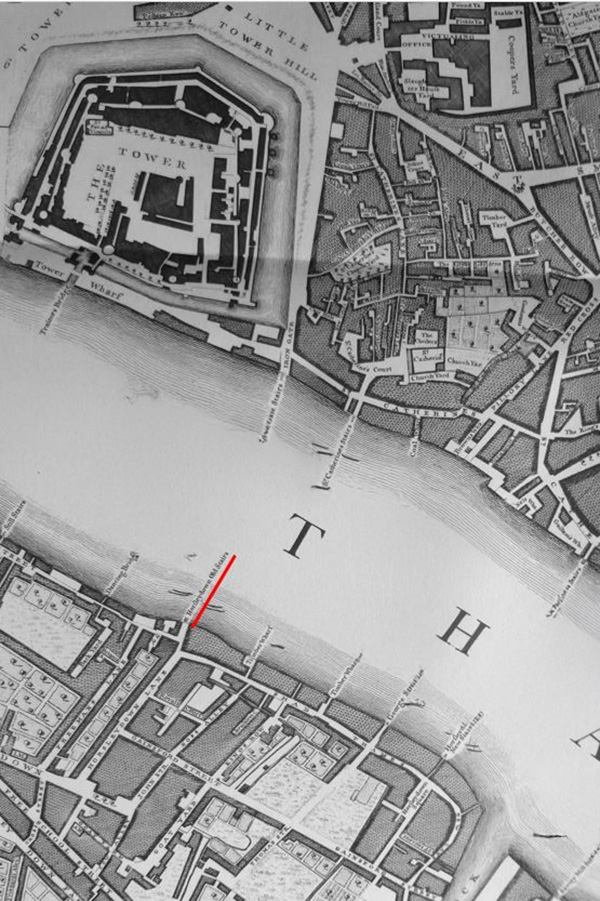

Once the German ship Lütcken entered River Thames, it continued to the Horselydown dock, opposite the London Tower (red dot).

The Horselydown dock extends into the River Thames (red line), with a close view of the London Tower on the north side of the river

Back to Germany and Snow's story...

Gluckstadt is on the Elbe, thirty miles below Hamburg. The evacuations of the seaman who died at Horselydown would, of course, be thrown overboard, according to universal custom. There might also be other cases of cholera in the shipping from the ports on the River Elbe, lying in the Thames; but if not fatal, or occurring beyond the metropolitan boundary we should not hear of them. From what occurred at the pump-well near Golden-square, in 1851, and at many other places in former epidemics, it is evident that the active material contained in the cholera evacuations is not destroyed by being mixed with water. Now, a morbid material which communicates any disease from one person to another, does so by the faculty of reproduction, which takes place during the so-called period of incubation, the disease which ensues being due, not to the matter first introduced, to the resulting crop. But no one will deny that everything which multiplies and reproduces its kind must not only be organic, but organized. Even yeast is organized: and smallpox matter consists chiefly of cells. The morbid material of cholera, therefore, is not dissolved in water so long as it retains its properties, but is only distributed; and the amount of water in which it is so distributed ought merely to diminish the chances of its reproducing the disease, but not necessarily to prevent its doing so.

Now, anything thrown into the Thames at Horselydown which can float goes backwards and forwards with the tide, ultimately, as a general rule, to reach the sea; but, in the meantime, it may pass up the Lea, or other tributaries, and also up any tidal ditches which communicate with these tributaries. If a sack of poppy seeds or mustard-seeds were thrown into the river at Horselydown, there is nothing more probable than that a few of them might find their way up the Lea, and the tidal sewer, and into the very pump-well at Abbey-row. I beg the attention of the reader to the following account of what occurred in previous epidemics. It will be remarked, in the meantime, that the first case of cholera at Abbey-row occurred seven days after the death of the seaman on board-ship at Horselydown.

The first case of Asiatic cholera in London in the autumn of 1848, was, according to an inquiry instituted by the then Board of Health, that of a seaman named John Harnold, who had newly arrived from Hamburg, where the disease was prevailing. The date of his death was the 22nd of September, like that of the seaman who died in the present year, and he died also at Horselydown, not, however, on board ship, but in a lodging near the shore.

The location of the first cholera case in London in 1848 is seen in Cruchley's 1846 map, living at 8, New Lane by Gainsford Street in Horsleydown (see red dot), just south of the River Thames and a few blocks east of the Horsleydown dock.