Return to John Snow Publications

Return to John Snow Publications

16. "Alkalescent urine and phosphatic calculi"

16. "Alkalescent urine and phosphatic calculi"

Source: Snow, John. London Medical Gazette 38, 20 November 1846, pp. 877-880.

Read at the Westminster Medical Society on November 6, 1846.

By John Snow, M.D.

Lecturer in Forensic Medicine at the Medical School, Aldersgate Street.

(Read at the Westminster Medical Society Nov. 7, 1846.)

Case in which a small quantity of urine remaining constantly in the bladder caused the decomposition of all that was secreted--experiments to show that a very small quantity will have this effect--the bladder cannot be completely emptied of urine when it contains a foreign body: this is the reason why it becomes incrusted with the phosphates, and why these salts form the chief part of so many calculi--cause of alkalescent urine in injuries of the spine, extreme old age, etc.--necessity of injecting the bladder with warm water in most cases of alkaline urine--benefit to be expected from this practice in stone in the bladder.

In a state of health the urine is generally slightly acid; it may, however, be for a short time neutral, or slightly alkaline, from articles of food or drink which contain potash or soda in combination with a vegetable acid--as apples, pears, grapes, etc., and saline draughts made with the citrates, tartrates, or acetates; the vegetable acid is digested, and the alkali passes into the urine. This condition of the secretion, however, is but temporary, and when the urine is strongly alkaline, or remains alkaline for days together, this must be looked on as a departure from the physiological condition.

When healthy urine is allowed to remain in a vessel, it is well known that it becomes alkalescent from decomposition; the urea it contains becoming changed into carbonate of ammonia. In paralysis of the bladder, when it remains constantly distended, and the urine dribbles away to make room for what is secreted, it is known to become offensive and ammoniacal. The same change of the urine takes place also in some cases of paraplegia, of enlarged prostate, and of stricture, when the bladder remains full for some time.

In the latter part of 1842, I had a patient suffering from incontinence of urine after a very tedious labour: when was applied to about the circumstance, I found the urine very ammoniacal, and containing a good deal of phosphate of lime in a state like mortar, the patient suffering much from excoriation of the genital organs. On introducing a catheter I found that about a table-spoonful of urine remained constantly in the bladder. After this viscus had been injected with warm water, the urine which flowed all the remainder of the day was free from alkalescence, and tolerably healthy. Here was a case, then, in which the continuance of about half an ounce of urine in the bladder caused the decomposition of all that passed through it. In order to see the bearing of this circumstance on a number of cases in which the bladder cannot be completely emptied, including, as I shall presently show, stone in the bladder, it became desirable to ascertain if a still smaller quantity remaining in that organ might not have a similar effect. With this view I performed experiments in the following manner. About half a pint of newly-voided urine was put into a glass vessel which terminated at the lower part in a tube of minute calibre, through which it dropped into a glass jar below, at the rate of about twelve drops in a minute, which is about an ounce and a half in an hour, that being not far from the quantity usually passing into the bladder from the ureters. The vessels were kept near the fire at the temperature of 100°. At the end of six or eight hours, when the urine had all dropped into the lower vessel, it was emptied, all but about thirty drops, and the upper glass, which served as a funnel, again replenished. It was found that the urine in the lower vessel became decomposed generally in about twenty-four hours--in about the same time, in short, as urine preserved at the same temperature from the beginning of the experiment, the time varying according to the quality of the urine. It generally became quite fœtid in two or three days, at all events highly alkalescent, and remained so as long as the experiment was continued, always fresh and acid in the upper vessel, provided it was washed out occasionally, and always decomposed in the lower one, although the urine, except a small fraction of it, was of the same age in both.

It is well known that an alkalescent state of the urine, and a deposition of the phosphates, usually coexist. The decomposition of urine, whether it takes place in or out of the bladder, is accompanied by the precipitation of the earthy phosphates. The ammonia resulting from the decomposition of the urea and animal matter of the urine combines with the phosphate of magnesia naturally present in solution to form the insoluble triple phosphate; it also combines with part of the phosphoric acid, which holds the lime in solution as a superphosphate, leaving a neutral phosphate of lime, which is insoluble. I have observed that minute crystals of triple phosphate very often begin to appear, as a delicate cloud, in urine that is kept before it has lost the property of reddening litmus. This observation I consider of importance, as it shews that the presence of these minute crystals in acid urine at the moment it is voided does not necessarily depend on an excess of phosphates. When the decomposition of the urine takes place to any great extent in the bladder, so that it becomes strongly ammoniacal, it irritates the mucous membrane, and causes it to secrete a quantity of phosphate of lime, or of phosphate and carbonate of lime, mixed with the mucus; this comes away with the urine, if there is no calculus or other foreign body in the bladder to which it may adhere. In the case of incontinence of urine to which I have alluded, the mucous membrane of the upper part of the vagina also secreted a quantity of phosphate of lime, apparently from the irritation of ammoniacal urine coming in contact with it. Dr. Chowne examined this patient with me.

When there is nothing to interfere with the healthy function of the bladder, it completely empties itself at intervals of a few hours by a vigorous contraction; and if we examine into the various circumstances which may prevent the complete emptying of the bladder, we shall find that they are all liable to be followed by an alkalescent state of the urine and deposit of phosphates. We will take, first, the instances of foreign bodies in the bladder. One of the symptoms of their presence is the occasional sudden stoppage of the stream of urine before the bladder is emptied; in addition to this, it is evident that the bladder can seldom contract around a foreign body so exactly as completely to expel all the urine; and moreover, calculi and nearly all other foreign bodies which gain admittance to the bladder, are porous, and contain urine imprisoned in their pores; accordingly it is a general law, with extremely few exceptions, that foreign bodies in the bladder become incrusted with the earthy phosphates. The usual explanation of this phenomenon, in which Dr. Prout, Sir B. Brodie, and others, agree, is that the foreign body causes chronic inflammation of the bladder, accompanied with a secretion of alkaline mucus which decomposes the urine: but a pea, or a bit of fibrine, or any other substance not of a nature to cause even irritation, is as certain to form the nucleus of a phosphatic calculus as the most hard and angular; and in most recorded cases there has been a total absence of symptoms of chronic inflammation at the time a foreign body was becoming incrusted; consequently, whilst I am ready to admit that the usual explanation may be true in some cases, and may act as a secondary or an auxiliary cause in others, there can be no doubt that the explanation now given is the correct one for most instances, as it shews a physical cause which can scarcely fail to be in operation. Vesical calculi are themselves foreign bodies, and consequently we find that every calculus, whatsoever its nature, is liable to become incrusted with the earthy phosphates; even the strongly acid state of the urine which usually prevails where there is uric acid calculus being generally overcome; whilst, on the other hand, the phosphatic incrustation is scarcely ever covered with any other deposit, but goes on increasing, the phosphatic deposition, when once it has commenced, being a cause of its own continuance. Mr. Taylor only alludes, in the Catalogue of the Calculi in the College of Surgeons, to two phosphatic calculi which became covered by another deposit, one in the museum of the College, in which the secondary deposit is oxalate of lime, and the other in the museum of St. Bartholomew's Hospital, in which it is uric acid.

When a catheter is introduced, if the bladder is not paralysed, it will contract as the urine flows, and be completely emptied, or nearly so; but if the catheter is left in the bladder, this viscus does not of course continue constantly in a state of active contraction, but is collapsed, and no doubt allows a small quantity of urine to remain in it, more or less, according to the position of the patient and the catheter: consequently we find that a catheter can seldom be left for two or three days in the bladder without inducing an alkalescent state of the urine, and becoming incrusted with the phosphates.

Dr. Prout, Sir B. Brodie, and numerous observers since, have remarked that injuries of the spine are liable to be followed by alkaline urine. This has usually been thought to depend on an altered secretion by the kidneys, arising from impaired nervous influence; it has been found, however, in various cases of disease and injury of the spine, that the urine, although alkaline in the bladder is acid when first secreted by the kidneys. Dr. Golding Bird (Med. Gaz. vol. xxxii, page 10; Urinary Deposits, 2d edition, p. 222.) accounts for this change by supposing that the healthy bladder preserves its contents from decomposition by its vital endowments, and that this property of the bladder is impaired by injuries and other affections of the spine; and Mr. Curling (Ibid. [that is, Med. Gaz.] vol. xiii, p. 76.) supposes that, when the bladder loses its sensibility from spinal lesion, it begins to secrete unhealthy alkaline mucus, which decomposes the urine. Now I have observed that healthy urine will keep fresh out of the body at blood-heat as long as it ever remains fresh in the bladder; and, with respect to the change in the mucus, there is every reason to believe that in these cases it is the consequence, and not the cause, of the alkalescence of the urine. Since the experiments I have related, we are in a position to give a more satisfactory explanation, and one which fortunately suggests a remedy of easy application. The explanation is, that the detrusor urinæ, like other muscles, is liable to various degrees of loss of power, besides total paralysis; and that, when it is weakened, along with the other muscles, by injury or disease of the spine, it can empty the bladder in a great measure, but cannot contract in that vigorous and complete manner necessary to expel the last drops of urine; and that thus a source of the decomposition exists. It is not improbable that, when the bladder is long occupied by highly alkalescent urine, the decomposition may be propagated in course of time in a retrograde manner along the ureters to the kidneys, and ultimately destroy the patient. This seems the best solution of certain cases in which phosphatic calculous matter is found in the pelvis of the kidney after death in persons who have suffered from injury or disease of the spine.

Dr. Prout (Stomach and Urinary Diseases.) has taught us that a state of great nervous irritability and depression is characteristic of the phosphatic diathesis, and leads to the secretion of alkaline urine by the kidneys. Now I have observed that an alkalescent state of the urine kept up by a local cause in the bladder leads to great depression and debility; and it is not improbable that general nervous and muscular debility may be a cause of alkaline urine by preventing the proper emptying of the bladder: consequently, whilst I do not dispute the existence of the phosphatic diathesis in the proper sense of the term--viz. the secretion of the phosphates in excess by the kidneys--I am inclined to believe it rare. The urine is often alkalescent in the decrepitude of extreme old age. We can now perceive the reason, since the muscular tunic of the bladder must of course partake of the debility common all the voluntary muscles.

Simon, of Berlin, has noticed an alkaline state of the urine in typhus, generally when comatose symptoms are setting in. Now, since sensation and volition, as regards the bladder, are often totally lost in typhus, it is almost certain that this organ must frequently suffer a partial loss of function, when, although still able to void the urine, it will not expel it completely. Under these circumstances the urine ought to be alkalescent in the bladder, and continue so till during convalescence the patient is able to empty the bladder properly.

The indications of treatment arising from these views of the subject are obviously to do for the bladder what it is incapacitated for doing of itself: to remove that little leaven of decomposition which alters the whole of the urine as fast as it flows into the bladder. The way to do this is to introduce a catheter, and inject warm water, to wash the bladder thoroughly out. The operation of injecting the bladder is, I believe, but little practised except in some states of disease of its mucous membrane; but I have no doubt it will be found the most efficacious treatment in nearly all cases of alkalescent urine. Mineral acids may be a very useful adjunct to this practice, but hitherto they have been far from successful in what has been called the phosphatic diathesis; and it is not to be expected that any quantity of acid, which can safely enter the circulation, and be separated by the kidneys, will be able to counteract such a powerful cause of phosphatic urine as I have pointed out. In the case of incontinence of urine to which I have alluded, the injection of the bladder, by removing the ammoniacal state of the urine, at once relieved the greater part of the patient's sufferings, and its repetition every day for a few weeks, until the bladder began to regain the power of retaining and expelling its contents, preserved the urine in a pretty healthy condition, and no doubt prevented inflammation, thickening, and contraction of he bladder, and perhaps spreading of disease to the kidneys. We may expect, at least, as much benefit in injuries of the spine, and numerous other cases; we may hope to prevent the formation of phosphatic calculi in many instances, and may reasonably expect to have a much greater power over vesical calculi of every kind than we have hitherto possessed without a serious operation. We may hope not merely to prevent their enlargement, but to get them to dissolve. Dr. Prout is of opinion--and there is every reason to believe it is a sound one--that healthy urine is the best solvent of all kinds of calculi which we can hope to possess; and washing out the bladder occasionally will undoubtedly be a great means of keeping the urine in a healthy state in cases of stone. The effect of injecting the bladder every day, or every other day, will be at once extremely beneficial on phosphatic calculi if the kidneys are secreting acid urine, as in most instances there is reason to believe they [880/881] are; and the great difficulty in the treatment of uric acid calculi has always been, the danger of inducing an alkaline state of the urine, which we should be unable to remove, and of thus causing the stone to increase, by a deposition of phosphates, faster than it has increased before: but, since we know how easily such a condition can be removed under the circumstances, we can give Vichy water, citrate of potash, and other appropriate remedies for excess of uric acid, without fear.

54, Frith Street, Soho Square.

Nov. 9, 1846.

Return to John Snow Publications

Return to John Snow Publications

17. "Case of strangulation of the ileum in an aperture of the mesentery"

17. "Case of strangulation of the ileum in an aperture of the mesentery"

Source: Snow, John. London Med. Gazette 38, 18 December 1846, pp. 1049-1052.

By John Snow, M.D., (Read at the Royal Med. and Chir. Society, June 23d, 1846).

The subject of the following case was the patient of Mr. Marshall of Greek Street, and I am indebted to him for the following account of her illness, having seen her during life myself only at his last visit.

Mrs. Oliver, 24 years of age, of good constitution, in the 8th month of her first pregnancy, was seized early on Saturday morning, March 21st, 1846, with rather severe pain, extending over the whole of the belly, of an intermitting character, being increased at intervals varying from a quarter of an hour to half an hour. There were sickness and vomiting, but little or no tenderness on pressure of the abdomen. The pulse was about 80: the bowels had been moved by castor oil. She thought her labour was coming on, but the os uteri was not at all dilated. Supposing that the pain depended on irregular spasmodic action of the intestines, a grain and a half of opium, and a carminative mixture, were administered. In the evening the pain had somewhat abated, and the vomiting had nearly ceased.

22d.--She had slept very little during the night; the pain was as severe as on the previous morning, with shorter intervals of intermission, and the vomiting had returned. Opiates were continued at intervals, and effervescing and cathartic draughts. In the evening the breathing was accelerated, and the pulse was upwards of 100: there was slight distension of the bowels from flatulence. An enema was administered, and was followed by what the nurse considered to be a copious and healthy motion, but it was not seen by me. She now complained of thirst.

23d.--She had passed another restless night. The pulse was now 120, and full;the breathing extremely hurried, and the thirst very great. The countenance was anxious. Sixteen ounces of blood were abstracted from the arm, to the great relief of the dyspnia; the pulse was not diminished in frequency. To take calomel and opium, and effervescing draughts. The clyster was repeated, but no fecal evacuation followed.

24th.--The vomiting continued, and during the night a considerable quantity of dark green liquid was brought up; not, however, having a fecal odour. There was a little tenderness on firm pressure, and great tympanitic swelling of the abdomen. The countenance was somewhat improved since yesterday, but the pulse was very rapid--140. A repetition of the clyster, and a continuance of the calomel and opium, and the fomentations which had been employed throughout, were directed. She died four hours after this visit, on the 4th day of her illness.

Examination 24 hours after death.--The abdomen was tympanitic and very much swollen, and a great quantity of dark green liquid, similar to that which had been vomited, had flowed out. The stomach and small intestines were extremely distended with flatus; the only lymph observed was a little of a creamy consistence between two folds of small intestine in the center of the abdomen; this part of the intestine exhibited a reddish surface externally: the rest of the intestines were nearly of the natural pale colour, except the last portion of the ileum, about 18 inches of which were of a deep purple, approaching nearly to black, and lay in folds in front and to the right side of the ascending colon. The contents of the uterus being removed in order to bring this part more clearly into view, these folds of ileum were seen to be bound down hust in front of the junction of the cecum with the colon, and constricted as closely as if a thread had been twitched tightly round them. The band which held them down did not seem thicker than the smallest hempen twine; one end of it was continuous with the peritoneum covering the vermiform appendix at about three-fourths of an inch from its commencement, and the other with [1049/1050] the peritoneum covering the ileum, about an inch from its termination. The appendix vermiformis was doubled on itself at the junction of this band, and the process of peritoneum inclosing it was dragged upwards, so as to give the appearance of a tight ligament, extending from that point to the upper edge of the pelvis, in front of the right sacro-iliac symphysis. On Mr. Marshall's attempting to pass his finger under the band, it gave way, and liberated the strangulated ileum, but the parts still remained in an unnatural position; the ascending colon was twisted on itself, so that the cecum was turned with its inner edge outwards, the ileum entering on the outerside, and the origin of the vermiform appendix being on the anterior and external side; these intestines, however, were readily removed into their natural places. The coats of the dark-coloured portion of ileum which had been strangulated were much swollen from the great congestion. The stomach was pale externally; its mucous membrane was ashy brown, and gave way under the fingers. This viscus, and the duodenum, contained dark green fluid, and the jejunum and the ileum, down to the strictured portion, contained a good deal of yellow liquid feces; the colon was empty. The head of the fetus was closely fitted to the cavity of the pelvis, and the os uteri was dilated to the size of a half-penny, the membranes being unruptured.

On examining the preparation* (*now in the possession of Mr. Marshall) which accompanies this paper, it will be found that the vermiform appendix is enclosed within a double layer of peritoneum, which forms a kind of broad ligament, which is attached above to the cecum and ilium, and was attached externally and inferiorly to the iliac fossa and brim of the pelvis.

The hand could be passed behind this expansion. On the external side of the vermiform appendix there is an aperture in this membrane, with defined edges, through which the thumb can be passed, and behind the portion of it which extends with a curve from the vermiform appendix to the ileum, there is a pouch into which a finger can be passed for about two [1050/1051] inches. The thin membrane passing from the appendix vermiformis ceci to the ileum, and leaving the aperture through which the strangulation took place, forms an extension of the above-mentioned curve. It has been tied at the spot where it was broken.

The symptoms in this case were such as usually arise from any mechanical obstruction in the bowels. There was nothing to indicate the cause, or even the situation, of the obstruction; for there was not more pain at one part of the abdomen than another. The enlargement of the uterus, by displacing the small intestines upwards and to each side, was probably the immediate cause of the insinuation of the ileum through the aperture. This opinion is confirmed by the circumstance that, in the first of the two cases quoted at the end of this paper, in which the band causing the strangulation was, in size and situation, very much like the one in this case, the immediate cause of the strangulation was evidently a particular posture of the patient. The twisted state of the ascending colon was, no doubt, a consequence of the strangulation, or of the distenstion which followed it: a twisted state of the bowels has been met with in several cases of intussusception and strangulation by membranous bands. There are many cases on record of strangulation of the bowels in an aperture made by morbid adhesion of the vermiform appendix of the cecum with neighbouring parts; but the appearance of the membrane in this case, the absence of evidences of old inflammation in the abdomen, and the circumstance that the membranous band appears to be a natural continuation of a larger fold, lead me to consider it as a congenital production of peritoneum, leaving an aperture on the inner side of the appendix vermiformis similar to the one we see on its outer side.

The recorded cases which I have been able to find that most resemble this just detailed, follow as an appendix, but the authors do not offer any opinion as to whether the apertures were congenital or not: there is, however, one case of strangulation from a congenital malformation related by M. Moscati, p. 468, of the 3d vol. of the same Memoires. In that case the ileum gave off a branch 2.5 feet previous to its termination, in the form of a funnel, terminating in a ligamentous band about 5 inches in length, and attached by its other extremity to the mesentery, leaving an opening through which some loops of the ileum became strangulated. This branch, I conclude, was the remains of the ductus omphalo-mesentericus.

Mr. Thomas Morton and Mr. Prescot Hewett have informed me that they have seen the appendix vermiformis enclosed in a fold of peritoneum forming a kind of broad ligament.

I subjoin two cases translated from the Memoires de l'Academie Royale de Chirurgie:-

"M. de la Faye informed us in 1750 of a strangulation of the intestine by a similar band. Being invited to assist at the opening of a body in order to make a report in concert with the surgeon in attendance, he learned that the subject, who was newly married, had experienced on the night of his nuptials a very severe pain of colic, such as had occurred to him for the last seven years every time that he had lain with a women. On this occasion it was more violent than before, and followed by all the symptoms which accompany a volvulus. The patient died in thirty-six hours, notwithstanding all the assistance that could be rendered him in that short interval. The belly was swelled out like a balloon: on its being opened the cause of death was evident. On going over the intestines with care, there was remarked, at an inch from the termination of the ileum in the cecum, a band of the thickness of a strong thread, and of three finger-breaths in length, attached on one side to the appendix ceci, and on the other to the part of the mesentery nearest to that intestine. The ileum had passed under that band to the extent of a foot: the strangulated portion was collapsed and inflamed. From the stomach to the seat of strangulation the intestinal canal was very much distended, and the part beyond the stricture was in the ordinary state. The band must have been vascular, for it was black and already gangrenous, so that it required only the slightest effort to break it. If the patient could have lived till the rupture of this band had taken place, he might possibly have recovered."-M. Hevin on Volvulus, in the Mem. De l'Acad. Roy. de Chirurgie, p. 237, vol iv. quarto edition.

"On the 16th April, 1765, M. Sancerotte, Surgeon in Ordinary of the late King of Poland, Duke of Lorraine, opened the body of a man who had been brought to the hospital the evening before. He had been ill nine days with the usual symptoms of strangulated hernia, although there was no appearance of it externally. The pulse had always been small, with severe pain in the right lumbar region. There was an annular opening in the mesentery of a ligamentous consistence, through which had passed the cecum with a part of the colon, and a greater extent of the ileum. The swelling which came on, having changed the relative proportions, these parts of the intestine became strangulated, and not being able to disengage themselves they mortified, after having occasioned first bilious and then stercoraceous vomiting, as usual in such cases. These parts could be withdrawn through the aperture, after evacuating by a puncture the air which distended them."-Ibid. p. 239.

54, Frith Street, Soho Square.

Return to John Snow Publications

Return to John Snow Publications

18. "Table on the quantity of vapour of ether in 100 cubic inches of air, saturated with it at various temperatures"

18. "Table on the quantity of vapour of ether in 100 cubic inches of air, saturated with it at various temperatures"

Source: Snow, John. Medical Times 15, 23 January 1847, p. 325.

By John Snow, M.D.

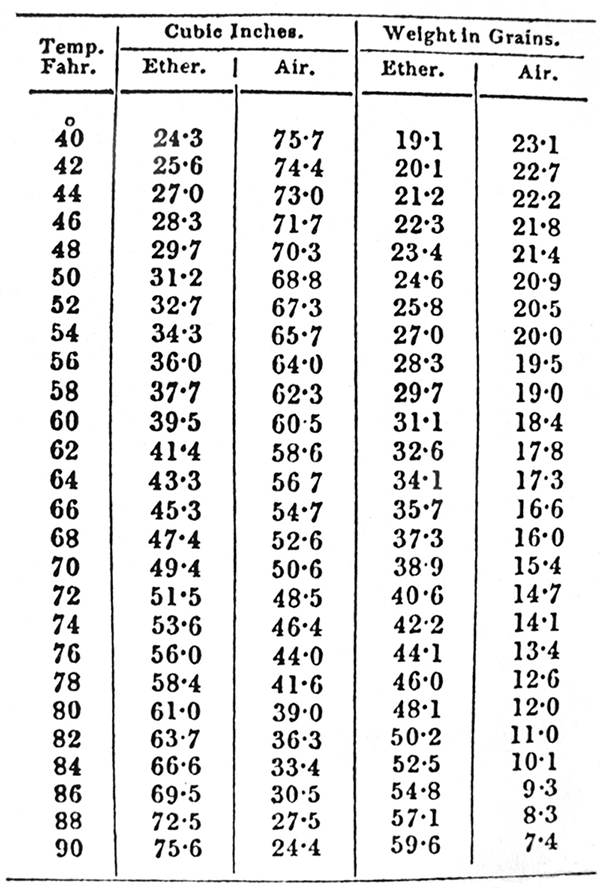

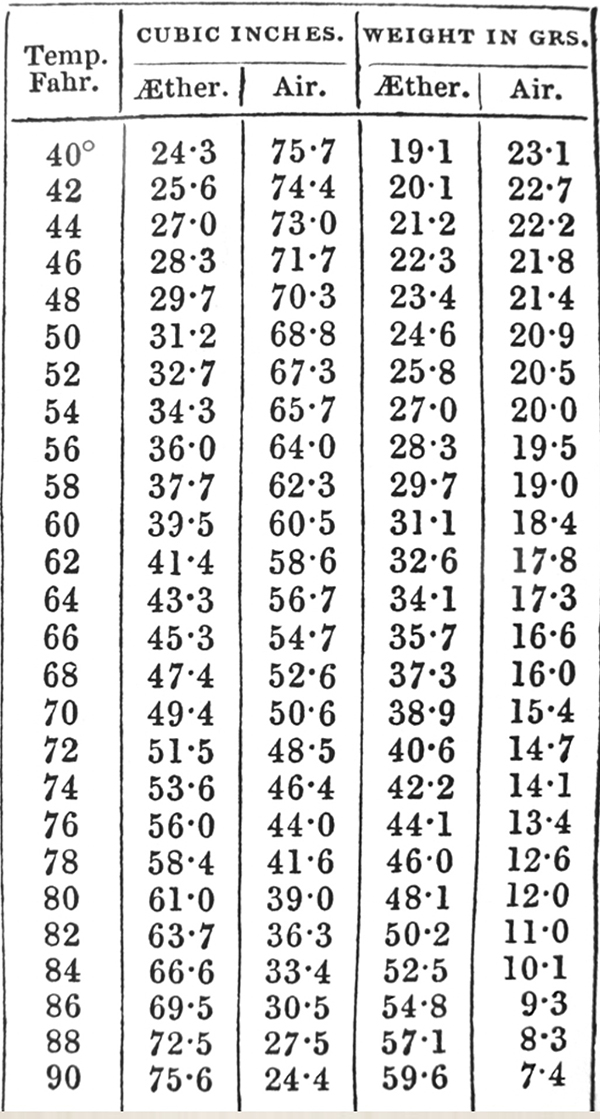

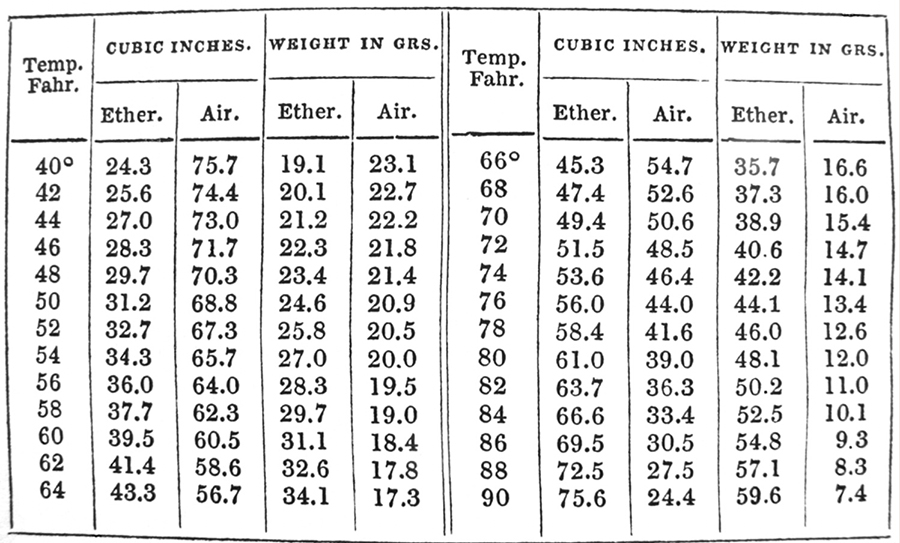

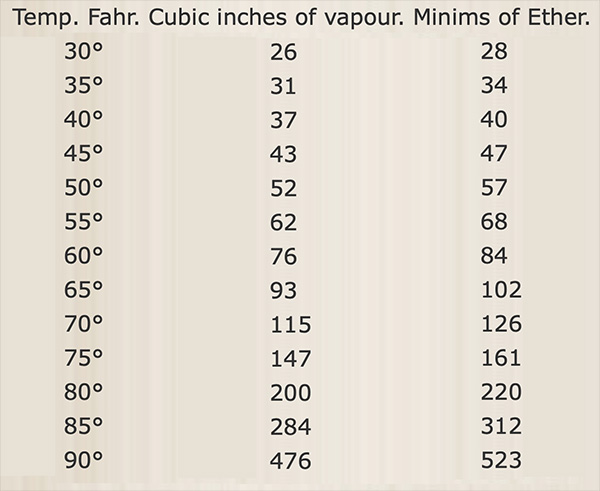

At about 45° the weights of vapour of ether and of air are equal, and at a little above 70° the volumes are equal.

The weights are calculated with the barometer at thirty.

Return to John Snow Publications

Return to John Snow Publications

19. "Table of the quantity of the vapour of ether "

19. "Table of the quantity of the vapour of ether "

Source: Snow, John. London Medical Gazette 39, 29 January 1847, pp. 219-220.

By John Snow, M.D.

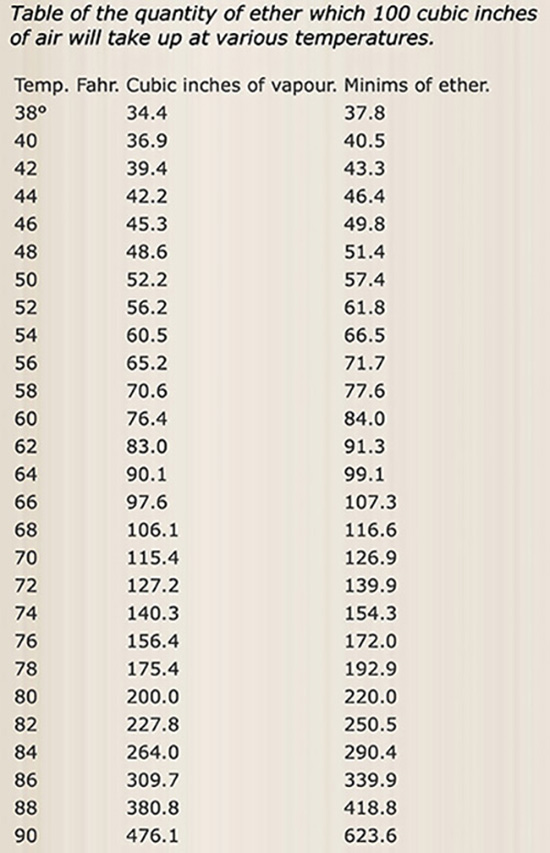

Table of the quantity of vapour of ether in 100 cubic inches of air, saturated with it at various temperatures.--

At about 45° the weights of vapour of ether and of air are equal, and at a little above 70° the volumes are equal. The weights are calculated with the barometer at 30.

From this it will be seen that the quantity of ether administered with air varies materially with the temperature.

Return to John Snow Publications

Return to John Snow Publications

20. "Table of the quantity of the vapour of ether in one hundred cubic inches of air, saturated with it at various temperatures"

20. "Table of the quantity of the vapour of ether in one hundred cubic inches of air, saturated with it at various temperatures"

Source: Snow, John. The Pharmaceutical Journal 6, 1 February 1847, p. 361.

By John Snow, M.D.

At about 45° the weights of vapour of ether and of air are equal, and at a little above 70° the volumes are equal.

The weights are calculated with the barometer at thirty.

[The mixture of the vapour of ether with atmospheric air being highly explosive, surgical operations ought never to be performed under its influence by candlelight. The result of an explosion under such circumstances would be dreadful.--Ed.]

Return to John Snow Publications

Return to John Snow Publications

21-22. On the inhalation of the vapor of ether

21-22. On the inhalation of the vapor of ether

Source: Snow, John. London Med. Gazette39, 19 March 1847, pp. 498-502, 26 March 1847, pp. 539-542.

By John Snow, M.D., Lecturer on Forensic Medicine at the Medical School Aldersgate Street.

PART 1

It will be at once admitted that the medical practitioner ought to be acquainted with the strength of the various compounds which he applies as remedial agents, and that he ought, if possible, to be able to regulate their potency. The compound of ether vapour and of air is no exception to this rule, although it might be supposed to form one, as the practitioner stands by to watch its effects. For, in the first place these effects vary materially according to the proportion of vapour given with the air, and in the next place, there is a counter process going on with inhalation, viz. exhalation. This increases with the amount of ether absorbed into the blood, and there arrives a point at which the exhalation may equal and just balance the inhalation, if the vapour be very much diluted; and this may occur before insensibility is produced. It is to this circumstance that we are to attribute the origin of the opinion that there are some persons - hard drinkers, for instance, - who are proof against the influence of the vapour. There may be persons on whom it does not act favourably, but I believe that no sentient being is proof against its influence.

It occurred to my mind that by regulating the temperature of the air whilst it is exposed to the ether, we should have the means of ascertaining and adjusting the quantity of vapour that will be contained in it: for the proportion of vapour in any given volume of air saturated with it at any particular temperature, is to the whole volume as the elastic force of the vapour at that temperature is to the atmospheric pressure at the time and place.

This is true of all vapours in contact with the liquid which gives them off. Now the elastic force of the vapour of ether has been investigated by Dalton and Ure. Imade some experiments with air and ether in graduated tubes over mercury, and found that the quantity of ether vapour taken up at various temperatures corresponded with calculations made according to the formula for the elastic force of the vapour of ether, given by Dr. Ure in his paper on Heat, in the Philosophical Transactions for 1818. I accordingly made use of his table and formula, as I stated at the Westminster Medical Society, in constructing the table published in the [London] Med. Gazette on Jan 29. The ether I used was not altogether free from alcohol, and I concluded this must have been the nature of the ether used by Dr. Ure in his experiments on the elastic force of its vapour; for on making observations afterwards on washed ether, and on every kind of ether over water, (for it then becomes washed,) I found the quantity taken up by air somewhat greater; but the geometrical ratio of increase in the quantity, according to temperature, is the same, as I have ascertained by very numerous observations at all the usual atmospheric temperatures. To make the table I constructed correct for washed ether, which is always used for inhaling, it is necessary to subtract four degrees from the various temperatures; for instance, the numbers opposite 40° are correct for 36° and so on. The ether I first used in my observation boiled at 104°. Washed ether boils at 100°, and if entirely deprived of its water by potash, at 98°. So long as ether contains no alcohol itsspecific gravity does not much influence the elastic force of its vapour, nor consequently the quantity that will mix with air; for water, having a much weaker affinity for ether than alcohol has, exerts less influence over its volatility.

The quantity of vapour of ether which air will take up at different temperatures, may be readily seen by introducing some ether to a measured quantity of air in a graduated receiver over the pneumatic trough, and noting the expansion which takesplace, and the temperature of the air within. The vapour may be washed out of the air by passing it through a quantity of water, and the air may be again measured,when the experiment will have been both synthetical and analytical. The most convenient and satisfactory way of investigating this subject, however, is over mercury, by means of a graduated tube, bent in the form of Dr. Ure's eudiometer, the open leg being the longest. Pass a portion of air into the sealed leg of the tube, about as much as will fill one fourth of it, the quantity being carefully noted, whilst the mercurial level is preserved in the two branches of the tube, andthe required temperature attained by immersing the syphon over its sealed branch,in water contained in a tall glass jar. A great portion of the mercury being withdrawn from the open leg by a long narrow tube, a few drops of ether may be introduced by means of the same tube through the mercury to the air in the sealed leg, by inclining the eudiometer a little, and using a little pressure with the breath on the surface of the ether.

By plunging the eudiometer in water at various temperatures, making a correction for the slight expansion and contraction which takes place in the air itself, from the increase and diminution of heat, and keeping the surface of the mercury level in the two legs, a number of observations may be made in a short space of time; and by washing the ether out of the air afterwards, and observing that the quantity of air is the same as at first, the whole of the observations will be verified.

The following table is suitable for washed ether which boils at 100°, and is quite free from alcohol but not altogether free from water; this being the kind of ether which is usually, and I think very properly, used for inhaling. The barometer is supposed tobe stationary, and at 30°. This table is formed on a different plan from the former, to shew the quantity of vapour that air will take up; and as the air is made a fixed quantity, and the variation of the ether all exhibited in one column, the influence which temperature exerts over it is rendered more apparent to those unaccustomed for a long period to arithmetical calculations. A table formed in this manner is the most correct way of exhibiting the subject, because, since the vapour of ether is absorbed as fast as it arrives at the pulmonary air cells, the quantity inhaled will be influenced rather by the volume of the air, than by that of the mixture of air and vapour, provided the patient's respiration is not obstructed, and it never should be, by the apparatus.

With the assistance of the above table we can determine the proportion of ether to air, and by measuring the ether consumed in an operation, the quantity of air, as well as of vapour, breathed per minute, or throughout the inhalation, can be easily determined by rule of three, and I shall state it in some of the cases I have to relate. This, however, can only be done when an apparatus is used which allows the temperature of the air passing through it to be accurately determined and regulated. The instruments at first used in America and in this country did not allow of any regulation of temperature, but were always used at that of the apartment, whatever it might be, and this afforded no index to the quantity of vapour taken up, for the evaporation of ether in a glass vessel containing sponges cools the air, more or less, according to the thickness of the glass and other circumstances, and it leaves the apparatus many degrees colder than it entered, as may be ascertained by passing air through an apparatus of this kind, and noting the temperature with a delicate thermometer. Glass and sponge being bad conductors of heat, the caloric required to convert the ether into vapour is taken in a great measure from the air passing through the apparatus, it stemperature being thereby reduced, and the quantity of ether which it will take up diminished. Instruments with compartments for warm or hot water, without the means of regulating the temperature of the whole apparatus, are still more objectionable than the former, for by them there is a risk of administering all vapour and no air. Hot water ought never to come near an apparatus for theinhalation of ether nor even warm water, and when its temperature approaches totepid it ought to be carefully regulated.

All that was required to regulate the temperature of both the ether and the air, and,consequently of the resulting mixture, was to bring them into proximity with substances having a good capacity for, and a good power of conducting, caloric.The first we have in water, and the second in the metals; therefore, by placing the ether in a metal vessel, and that vessel in a basin of water brought to the desired temperature by mixing cold and warm water together, the object was attained. Two or three pints of water supply the caloric abstracted in the evaporation of an ounce or two of ether without being much reduced in temperature; and, as the water never requires to be many degrees either above or below the heat of the apartment, its temperature is but little altered by the surrounding air during the short time of an operation.

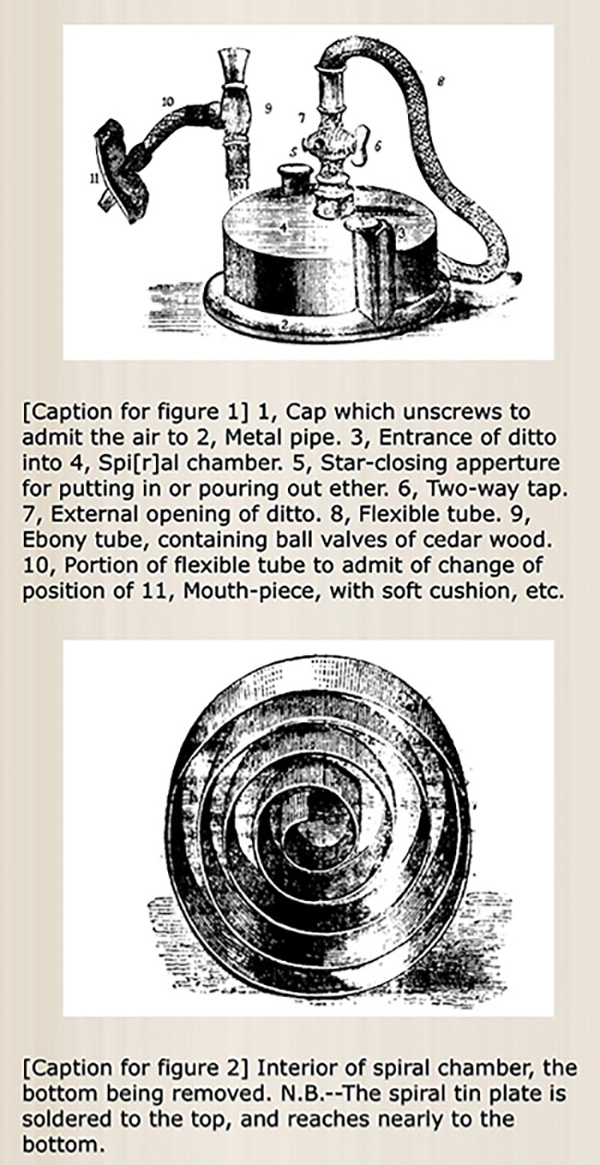

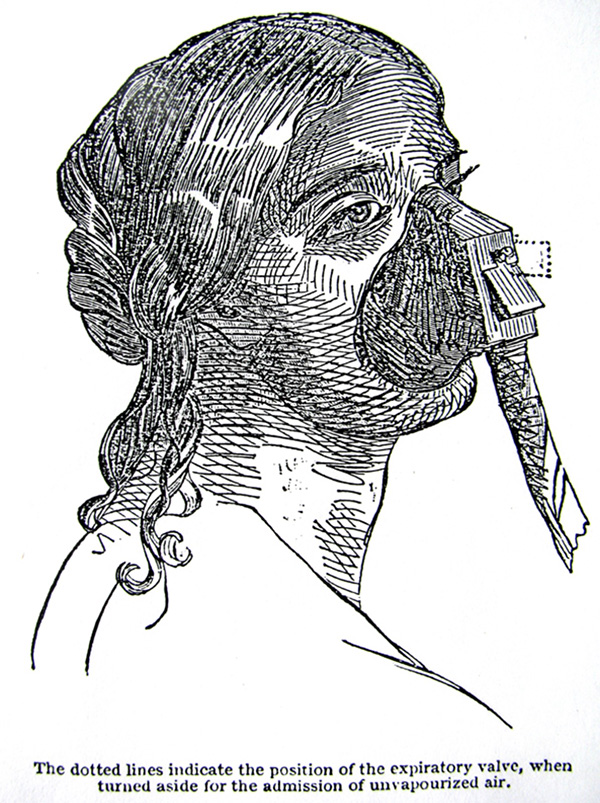

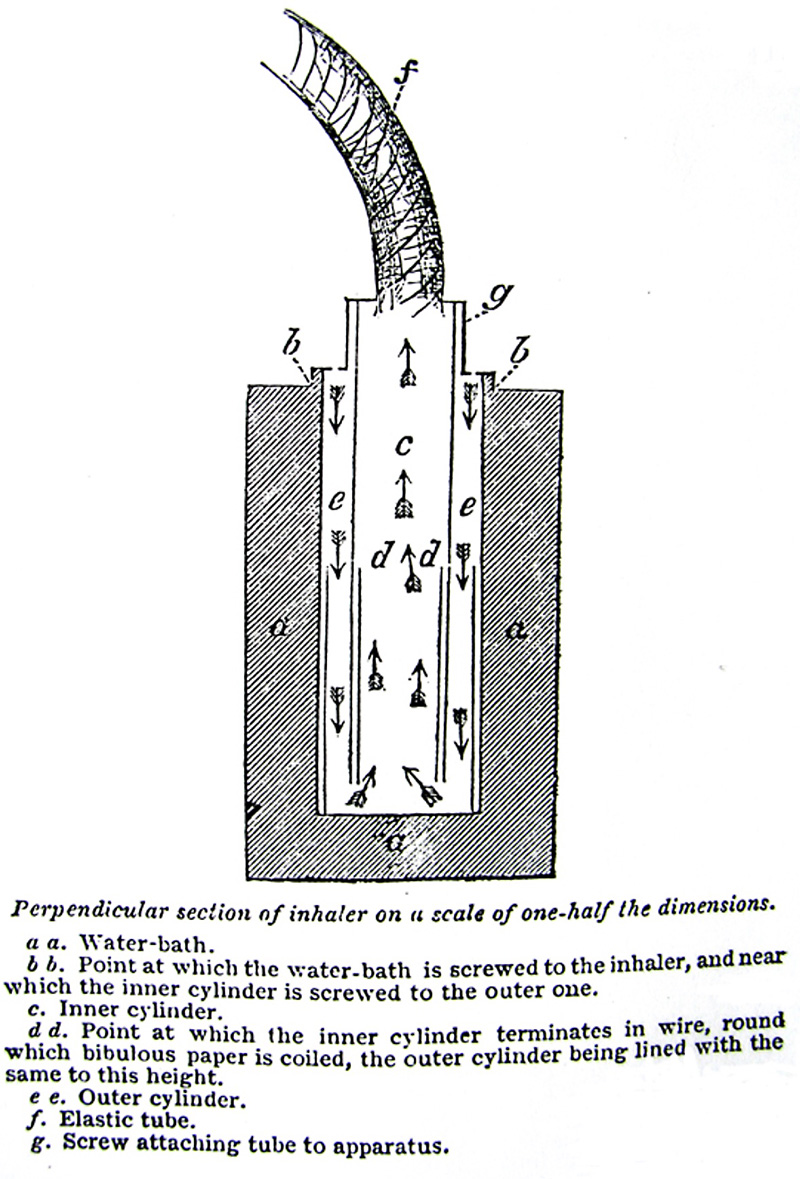

To ensure the saturation of air with the vapour of ether, all that is required is that the air should come in contact with the ether. The larger the surface of the ether exposed, the greater the evaporation, under ordinary circumstances, because it is exposed to more air, but the elastic force of the vapour of ether, at all temperatures above the freezing point of water, is such, that, to saturate the quantity of air which one person can breathe, requires no very great extent of surface. There is no necessity to make the air force its way through the ether, or pass with difficulty through sponges: the ether lies imprisoned in the liquid state only whilst kept down by air already saturated with its vapour, and it is ready to project itself immediately into every fresh portion of air that has access to it, as every one is well aware who has made any experiments with it in jars over the pneumatic trough. However, to insure that the air should come in contact with the ether, and to prevent its being cooled by the contact, I had the interior of the apparatus constructed on the principle of the inhaler of Mr. Jeffreys, described in the Med. Gaz. Feb. 1842, which I had always considered the best inhaler for aqueous vapour. The coils of the tin volute are not so numerous as in the latter but they are amply sufficient for so volatile a liquid as ether. The air has to pass through a pewter pipe before it enters the spiral chamber; by this means it gains the temperature we may wish, and the further advantage is attained, without the impediment of a valve, of preventing evaporation of ether into the room between the inspirations of the patient. In the other instruments that I have seen, there is either a waste of ether in this way, or else there is a valve to admit the air into the inhaler, which must be opened by means of the muscular effort of the patient. The vapour does not find its way in a retrograde direction through 18 inches of curved pipe between the inspirations of the patient; and consequently, whilst there is no impediment to the free passage of air through the apparatus, no ether escapes till it has been breathed by the patient. The mouth-piece I have adopted is furnished with the cushion and India-rubber described by Mr. Tracy in a recent number of the Med. azette. I use, however, the common, and not the vulcanized India rubber, as I understand that the latter frequently, if not always, contains sulphuret of arsenic. As the sudden access of air highly charged with ether produces irritation and cough in some persons, I was desirous ofhaving the means of diluting the vapour to any extent, and Mr. Ferguson, of Giltspur Street, who has taken great pains to carry my wishes into effect, got a tap cast of wide caliber, opening two ways, by means of which the patient can begin by breathing unmedicated air, and have this gradually turned off as the etherized air is admitted in its place. This tap [500/501] offers the further advantage of enabling the medical attendant to keep up the state of insensibility during an operation by a more diluted vapour than that which was necessary to produce that state. All the passages through the apparatus are not less than five-eights of an inch in diameter.

Those cases of administration of ether are generally most successful in which the insensibility is produced in a short space of time; forinstance, from a minute and a half to three or four minutes after the process is fully begun. This we might expect for various reasons; amongst the rest,that no process of inhaling can be carried on without interfering somewhat with the natural state of the respiration and embarrassing to some extent thecirculation; therefore the shorter the process the better.

Although the patient may begin by breathing air, and the ether may be introduced by degrees, yet, by turning the tap a little at each inspiration, the transition may be effected in from a quarter to half a minute. It is necessary to the success of the process that the nostrils and mouth be carefully closed. The patient should have plenty of air, it is true, but it should all come charged with the vapour, otherwise there can be no certainty about the process, and the patient will be more likely to become inebriated than insensible. The temperature I have nearly always applied has been from 65° to 70°, between which points the proportion of vapour and of air does not differ much from equality (to be continued in Part 2).

PART 2

In those instances in which I have watched the pupil of the eye narrowly, I have observed it to dilate, as the patient is getting under the influence ofthe vapour. This dilation is, however, but transitory, and the pupil usually becomes somewhat contracted, and the eye turned up as in sleep, as soon as the patient becomes insensible to pain. The breathing at the same time becomes deep, slow, and regular, and there is an absence of voluntary motion and a relaxation of the muscles, the orbicularis muscle ceasing to contract again on the eyelids being raised by the finger. An operation maybe commenced in this condition of the patient, with confidence that he will remain as passive as a dead subject. This having been found to be the case, in order to maintain the insensibility without further increasing it, I am inthe habit of partly turning the two-way tap to dilute the vapour; and it has seemed to me that by turning it about half way, so as to admit an equal quantity of external air, and reduce the vapour to about 25 per cent, that object has been attained: but a more extensive experience is required on this point, and perhaps the proportion required may vary in different patients. This method of continuing a more diluted vapour I have found to keep up the insensibility better than leaving off the process and resuming it by turns. But if the respiration becomes too slow, or at all stertorous, or if the pulse becomes very small or feeble, the nostrils should be at once liberated, and the admission of fresh air will afford immediate relief. I should think it unsafe to fasten a mask on the face, by means that would interfere with the instantaneous admission of air, for on one occasion I saw an animal killed by ether by a momentary delay. It was placed in a small glass jar, and when it appeared to have had as much of the vapour as it could bear, I attempted to take it out, but could not reach it with my fingers, and whilst turning round for some means of extricating it, it expired.

In nineteen cases out of twenty in which the pulse was carefully noticed, it increase in frequency during the inhalation, often very much, becoming as frequent as 180 in the minute in some patients in whom, from debility, it was frequent before the process began. Generally the pulse has also become smaller and more feeble. In one instance, that of a lady reduced in strength by malignant disease, it became smaller, but not more frequent; and as soon as the inhalation was discontinued, it became fuller and stronger than before the inhalation began. The pulse generally recovers its volume almost directly the inhalation is discontinued; in several instances, as in the above,becoming stronger than before: but it remains frequent for some minutes.The immediate effect on the circulation, of the absorption of the vapour in the lungs, appears to be an impediment to the flow of blood through the pulmonary capillaries. Less blood reaches the left side of the heart to be sent into the arteries, which diminish in caliber, but the heart contracts more frequently in order to keep up a supply. The escape of the vapour from the blood again seems to exert a contrary effect on the circulation, as evidenced, in general, by the pulse. I may perhaps be allowed to make a quotation bearing on this subject from a paper of mine in the Med. Gaz., vol. Xxxi.: - "As safreetida, ether, various essential oils, camphor, and other volatile medicines, relieve difficult and impeded respiration.... They are all separated from the blood in the lungs, and escape with the breath ... increasing very much the quantity of vapour which exhales from the pulmonary capillaries, and thus giving additional impetus to the blood: in this way lessening congestion and relieving its distressing symptoms. As this class of medicines promote the function of respiration, I will venture to call them diapnetics, from ??? and ????."

I have seen two cases in which the depressing effect of the inhalation was considerable, and was not followed by reaction directly it was discontinued.As this appears to have been the case in the instance attended with fatal result at Colchester, and related in the Medical Gazette of the 5th inst.,it may be desirable to enter into the particulars of one of these. A lady, 41 years of age, in pretty good health, the patient of Dr. Fredrick Bird, inhaled ether on the occasion of having a tumor removed connected with the external generative organs. She inhaled for eight minutes, during which time it was observed that the respiration was feeble and slow. The pulse, however, which had been about natural before the inhalation, became feeble and very frequent, and the patient began to struggle as if suffering from want ofbreath; the process was discontinued although she did not appear insensible, and the operation was commenced. She flinched and cried out at the first incision, although she did not afterwards remember the pain. She becamevery faint during the operation, although there was but little loss of blood,and it was necessary to give brandy, and lower the head to the horizontal posture. Consciousness soon returned, and as some sutures were made inthe skin, she spoke coolly of beginning to feel a little pain. The feeling of faintness continued more or less all night, but her recovery was very good. The apparatus in this instance was placed in water at 70°, being lower than the temperature of the room. Two fluid ounces of ether were put in, and three drachms remained; consequently 13 drachms were inhaled, equal to about 709 cubic inches of vapour; and as it was washed ether, each 115 cubic inches would be combined with 100 cubic inches of air; consequently only about 616 cubic inches of air were breathed, making 1325 cubic inches of airand vapour: but in eight minutes the patient ought to have breathed about 2400 cubic inches of air alone. The ether in this instance appeared to act as a sedative to the function of respiration, and the small amount of air breathed may perhaps account for the depressing effects.

In two or three instances there have been some struggling and a distended state of the superficial veins, the skin being rather purple, and the conjunctiv somewhat injected. In one instance this seemed to arise from cough being excited by the vapour, on account of the bronchial membrane being in an irritable state, and in the others I believe it arose from obstructed respiration, which in future may be avoided, rather than from the direct effect of the vapour. By the kindness of the surgeons to St.George's Hospital, I have had the honour of giving the vapour of ether at thirteen surgical operations - most of them important ones - in the hospital during the last six weeks, having the valuable advice of the surgeons, and occasionally also of one or two of the physicians to the hospital, to aid me in so giving it. It has been successful in altogether preventing pain in all the cases but one or two, and even in these there was but very little of the pain that there otherwise would have been; and there have been no ill effects of any kind following the inhalation of the ether. I allude to these cases toremark that five of the patients were children of various ages, from the fifth year upwards, and that they inhaled more easily than the adults generally did; that they were more quickly affected, generally becoming quite insensible in less than two minutes, and always without any struggling which sometimes occurred in the adults.

For a variety of reasons, and from close observations, I have arrived at the conclusion, that this difference has not arisen strictly from a different effect of ether on subjects ofdifferent ages, but from a cause within our control. The same inhaler was used in all, consequently the tubes were wider in proportion for children than for adults. I have described all the passages of the apparatus as not less than five-eights of an inch in diameter; but such is the description rather of what I wanted than of any instrument Ihave used. Valves and tubes such as were already in existence have been made use of, and the caliber in some part of its extent has always been contracted to half an inch, and this I consider only enough for a child, but not for the adult. As only half, and often not so much as half, of what is inhaled is air, it is particularly requisite that the [540/541] tubes should be wide. I am now getting elastic tubes, valves and mouth-tubes, made purposely for the apparatus three quarters of an inch in diameter, as wide, in fact, as the barrel of a fowling piece, and intend to give ether as fair a trial in adults as hitherto, I believe, it has had in children only.* (*Since the above was written, I have used these large tubes, and found them to answer my expectation.) The pipe admitting air to the ether will be five-eights, and all the passages for the air expanded by vapour, three-quarters of an inch in diameter. It may be supposed that there is no occasion tomake the tubes larger than the trachea, but something ought to be allowed for the friction of the air against the interior of the tubes.

With the assistance of the above table we can determine the proportion of ether to air, and by measuring the ether consumed in an operation, the quantity of air, as well as of vapour, breathed per minute, or throughout the inhalation, can be easily determined by rule of three, and I shall state it in some of the cases I have to relate. This, however, can only be done when an apparatus is used which allowsthe temperature of the air passing through it to be accurately determined and regulated. The instruments at first used in America and in this country did notallow of any regulation of temperature, but were always used at that of the apartment, whatever it might be, and this afforded no index to the quantity of vapour taken up, for the evaporation of ether in a glass vessel containing sponges cools the air, more or less, according to the thickness of the glass and other circumstances, and it leaves the apparatus many degrees colder than it entered, as may be ascertained by passing air through an apparatus of this kind, and noting the temperature with a delicate thermometer. Glass and sponge being bad conductors of heat, the caloric required to convert the ether into vapour istaken in a great measure from the air passing through the apparatus, its temperature being thereby reduced, and the quantity of ether which it will take up diminished. Instruments with compartments for warm or hot water, without the means of regulating the temperature of the whole apparatus, are still more objectionable than the former, for by them there is a risk of administering all vapour and no air. Hot water ought never to come near an apparatus for the inhalation of ether nor even warm water, and when its temperature approaches to tepid it ought to be carefully regulated.

All that was required to regulate the temperature of both the ether and the air, and,consequently of the resulting mixture, was to bring them into proximity with substances having a good capacity for, and a good power of conducting, caloric.The first we have in water, and the second in the metals; therefore, by placing the ether in a metal vessel, and that vessel in a basin of water brought to the desired temperature by mixing cold and warm water together, the object was attained. Two or three pints of water supply the caloric abstracted in the evaporation of an ounce or two of ether without being much reduced in temperature; and, as the water never requires to be many degrees either above or below the heat of the apartment, its temperature is but little altered by the surrounding air during the short time of an operation.

With respect to the psychological phenomena produced by ether, I have observed that consciousness seems to be lost before the sensibility to pain, and if an operation is commenced [i]n this stage, the patient will flinch, and even utter cries, and give expressions of pain, but will not remember it, and will assert that he has felt none.

Metaphysicians have distinguished between sensibility and perception - between mere sensation and the consciousness or knowledge of that sensation, though the two functions have, as they supposed, always been combined. Ether seems to decompose mental phenomena as galvanism decomposes chemical compounds, allowing us to analyse them, and showing that the metaphysicians were right. During the recovery of the patient, consciousness, which first departed generally returns first, and the curious phenomenon is witnessed of a patient talking, often quite rationally, about the most indifferent matters, whilst his body is being cut or stitched by the surgeon. I have never seen this insensibility to pain during the conscious state except where consciousness had been previously suspended. In the paper on the capillary circulation, in the Medical Gazette, to which I have alluded above, I offered the opinion that the pain of inflammation depended on a great increase of the natural sensibility of the inflamed part. Under the influence of ether we sometimes see the converse of this, viz. what would be pain reduced to an ordinary sensation; thus, some patients,whilst recovering their consciousness, feel the cuts of the surgeon without the smart. A nobleman, the patient of Mr. Tracy, of Hill Street, Berkeley Square, described the lancing of an abscess as the sensation of something cold touching the part; the manipulation of the abscess, which at another time would have been painful, he did not feel at all.

If the patient will remain silent during his recovery from the effects of ether, as he generally will, it is better not to trouble him with questions till he has perfectly regained his faculties, as conversation seems to increase the tendency to excitement of the mind that sometimes exists for a few minutes as the patient is recovering from the effects of ether. This kind of inebriation is sometimes amusing, but is not a desirable part of the effects of ether, more especially on so grave an occasion as a serious surgical operation; and therefore anything that may prevent or diminish it is worthy of attention. The children have all appeared to recover their consciousness very quickly, and without any kind of aberration of mind.

Any organic disease which impedes the flow of blood through the heart and lungs would seem to contraindicate the exhibition of ether by inhalation, and I should consider a hurried state of the circulation, such as that induced by strong labour pains, likewise to offer an objection to the process.

It was my intention to make some remarks on the probable way in which ether acts in suspending sensibility; but, as what I have already written is probably sufficient for one article, I will reserve that part of the subject for a future communication, and will be content, at present, to refer to a short abstract of some of my experiments and opinions which appeared in the number for Feb., 26.

In concluding, however, I should wish to observe that I am inclined to look upon the new application of ether as the most valuable discovery in medical science since that of vaccination. From what I have seen, I feel justified in the conclusion that ether may be inhaled for nearly all surgical operations, with the effect of preventing pain, not only with safety and without ill-consequences, where due care is taken, but in many cases with [541/542] the further advantage of improving the patient's prospect of recovery; the pain of an operation forming often a considerable part of what renders it dangerous, and many patients after ether, having seemed to recover better than might, without it,have been expected.

In the amputations performed at St. George's Hospital whilst the patients were under the influence of ether, it has been remarked, as was stated by Mr. Cutler, on Feb. 11th, that there has been an absence of the painful spasmodic starting of the stump, which usually renders it necessary for a nurse to sit and hold it for some hours after the operation.

54, Frith Street, Soho.

Return to John Snow Publications

Return to John Snow Publications

23. "On the inhalation of the vapour of ether"

23. "On the inhalation of the vapour of ether"

Source: Snow, John. British and Foreign Medical Review 23 (April 1847) pp. 573-576.

The full title of this periodical is the British and Foreign Medical Review or Quarterly Journal of Practical Medicine and Surgery, Vol. 23 is dated January - April 1847. [Note: contains extracts from article #22, i.e. in LMG 39, 26 March 1847, 539-542.]

By John Snow, M.D.

"In those instances in which I have watched the pupil of the eye narrowly, I have observed it to dilate, as the patient is getting under the influence of the vapour. This dilation is, however, but transitory, and the pupil usually becomes somewhat contracted, and the eye turned up as in sleep, as soon as the patient becomes insensible to pain. The breathing at the same time becomes deep, slow, and regular, and there is an absence of voluntary motion and a relaxation of the muscles, the orbicularis muscle ceasing to contract again on the eyelids being raised by the finger. An operation may be commenced in this condition of the patient, with confidence that he will remain as passive as a dead subject. This having been found to be the case, in order to maintain the insensibility without further increasing it, I am in the habit of partly turning the two-way tap to dilute the vapour; and it has seemed to me that by turning it about half way, so as to admit an equal quantity of external air, and reduce the vapour to about 25 per cent, that object has been attained: but . . . more extensive experience is required on this point, and perhaps the proportion required may vary in different patients. This method of continuing a more diluted vapour I have found to keep up the insensibility better than leaving off the process and resuming it by turns. But if the respiration becomes too slow, or at all stertorous, or if the pulse becomes very small or feeble, the nostrils should be at once liberated, and the admission of fresh air will afford immediate relief. I should think it unsafe to fasten a mask on the face, by means that would interfere with the instantaneous admission of air, for on one occasion I saw an animal killed by ether by a momentary delay. It was placed in a small glass jar, and when it appeared to have had as much of the vapour as it could bear, I attempted to take it out, but could not reach it with my fingers, and whilst turning round for some means of extricating it, it expired.

"In nineteen cases out of twenty in which the pulse was carefully noticed, it increase in frequency during the inhalation, often very much, becoming as frequent as 180 in the minute in some patients in whom, from debility, it was frequent before the process began. Generally the pulse has also become smaller and more feeble. In one instance, that of a lady reduced in strength by malignant disease, it became smaller, but not more frequent; and as soon as the inhalation was discontinued, it became fuller and stronger than before the inhalation began. The pulse generally recovers its volume almost directly the inhalation is discontinued; in several instances, as in the above, becoming stronger than before: but it remains frequent for some minutes. . . .

"I have seen two cases in which the depressing effect of the inhalation was considerable, and was not followed by reaction directly it was discontinued. . . . A lady, 41 years of age, in pretty good health, the patient of Dr. Fredrick Bird, inhaled ether on the occasion of having a tumor removed connected with the external generative organs. She inhaled for eight minutes, during which time it was observed that the respiration was feeble and slow. The pulse, however, which had been about natural before the inhalation, became feeble and very frequent, and the patient began to struggle as if suffering from want of breath; the process was discontinued although she did not appear insensible, and the operation was commenced. She flinched and cried out at the first incision, although she did not afterwards remember the pain. She became very faint during the operation, although there was but little loss of blood, and it was necessary to give brandy, and lower the head to the horizontal posture. Consciousness soon returned, and as some sutures were made in the skin, she spoke coolly of beginning to feel a little pain. The feeling of faintness continued more or less all night, but her recovery was very good. The apparatus in this instance was placed in water at 70°, being lower than the temperature of the room. Two fluid ounces of ether were put in, and three drachms remained; consequently 13 drachms were inhaled, equal to about 709 cubic inches of vapour; and as it was washed ether, each 115 cubic inches would be combined with 100 cubic inches of air; consequently only about 616 cubic inches of air were breathed, making 1325 cubic inches of air and vapour: but in eight minutes the patient ought to have breathed about 2400 cubic inches of air alone. The ether in this instance appeared to act as a sedative to the function of respiration, and the small amount of air breathed may perhaps account for the depressing effects.

"In two or three instances there have been some struggling and a distended state of the superficial veins, the skin being rather purple, and the conjunctivæ somewhat injected. In one instance this seemed to arise from cough being excited by the vapour, on account of the bronchial membrane being in an irritable state, and in the others I believe it arose from obstructed respiration, which in future may be avoided, rather than from the direct effect of the vapour. By the [574/575] kindness of the surgeons to St. George's Hospital, I have had the honour of giving the vapour of ether at thirteen surgical operations--most of them important ones--in the hospital during the last six weeks, having the valuable advice of the surgeons, and occasionally also of one or two of the physicians to the hospital, to aid me in so giving it. It has been successful in altogether preventing pain in all the cases but one or two, and even in these there was but very little of the pain that there otherwise would have been; and there have been no ill effects of any kind following the inhalation of the ether. I allude to these cases to remark that five of the patients were children of various ages, from the fifth year upwards, and that they inhaled more easily than the adults generally did; that they were more quickly affected, generally becoming quite insensible in less than two minutes, and always without any struggling which sometimes occurred in the adults. For a variety of reasons, and from close observations, I have arrived at the conclusion, that this difference has not arisen strictly from a different effect of ether on subjects of different ages, but from a cause within our control. The same inhaler was used in all, consequently the tubes were wider in proportion for children than for adults. I have described all the passages of the apparatus as not less than five-eights of an inch in diameter; but such is the description rather of what I wanted than of any instrument I have used. Valves and tubes such as were already in existence have been made use of, and the caliber in some part of its extent has always been contracted to half an inch, and this I consider only enough for a child, but not for the adult. As only half, and often not so much as half, of what is inhaled is air, it is particularly requisite that the tubes should be wide. I am now getting elastic tubes, valves and mouth-tubes, made purposely for the apparatus three quarters of an inch in diameter, as wide, in fact, as the barrel of a fowling piece, and intend to give ether as fair a trial in adults as hitherto, I believe, it has had in children only. [*footnote excluded from extract] The pipe admitting air to the ether will be five-eights, and all the passages for the air expanded by vapour, three-quarters of an inch in diameter. It may be supposed that there is no occasion to make the tubes larger than the trachea, but something ought to be allowed for the friction of the air against the interior of the tubes.

"With respect to the psychological phenomena produced by ether, I have observed that consciousness seems to be lost before the sensibility to pain, and if an operation is commenced [i]n this stage, the patient will flinch, and even utter cries, and give expressions of pain, but will not remember it, and will assert that he has felt none. Metaphysicians have distinguished between sensibility and perception--between mere sensation and the consciousness or knowledge of that sensation, though the two functions have, as they supposed, always been combined. Ether seems to decompose mental phenomena as galvanism decomposes chemical compounds, allowing us to analyse them, and showing that the metaphysicians were right. During the recovery of the patient, consciousness, which first departed generally returns first, and the curious phenomenon is witnessed of a patient talking, often quite rationally, about the most indifferent maters, whilst his body is being cut or stitched by the surgeon. I have never seen this insensibility to pain during the conscious state except where consciousness had been previously suspended. In the paper on the capillary circulation, in the Medical Gazette, to which I have alluded above, I offered the opinion that the pain of inflammation depended on a great increase of the natural sensibility of the inflamed part. Under the influence of ether we sometimes see the converse of this, viz. what would be pain reduced to an ordinary sensation; thus, some patients, whilst recovering their consciousness, feel the cuts of the surgeon without the smart. A nobleman, the patient of Mr. Tracy, of Hill Street, Berkeley Square, described the lancing of an abscess as the sensation of something cold touching the part; the manipulation of the abscess, which at another time would have been painful, he did not feel at all.

"If the patient will remain silent during his recovery from the effects of ether, as he generally will, it is better not to trouble him with questions till he has perfectly regained his faculties, as conversation seems to increase the tendency to excitement of the mind that sometimes exists for a few minutes as the patient is recovering from the effects of ether. This kind of inebriation is sometimes amusing, but is not a desirable part of the effects of ether, more especially on so grave an occasion as a serious surgical operation; and therefore anything that may prevent or diminish it is worthy of attention. The children have all appeared to recover their consciousness very quickly, and without any kind of aberration of mind.

"Any organic disease which impedes the flow of blood through the heart and lungs would seem to contraindicate the exhibition of ether by inhalation, and I should consider a hurried state of the circulation, such as that induced by strong labour pains, likewise to offer an objection to the process.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

"In concluding, however, I should wish to observe that I am inclined to look upon the new application of ether as the most valuable discovery in medical science since that of vaccination. From what I have seen, I feel justified in the conclusion that ether may be inhaled for nearly all surgical operations, with the effect of preventing pain, not only with safety and without ill consequences, where due care is taken, but in many cases with the further advantage of improving the patient's prospect of recovery; the pain of an operation forming often a considerable part of what renders it dangerous, and many patients after ether, having seemed to recover better than might, without it, have been expected. In the amputations performed at St. George's Hospital whilst the patients were under the influence of ether, it has been remarked, as was stated by Mr. Cutler, on Feb. 11th, that there has been an absence of the painful spasmodic starting of the stump, which usually renders it necessary for a nurse to sit and hold it for some hours after the operation.

(London Med. Gazette, March 26th, 1847.)

Return to John Snow Publications

Return to John Snow Publications

24. "To the editor of the Pharmaceutical Journal"

24. "To the editor of the Pharmaceutical Journal"

Source: Snow, John. The Pharmaceutical Journal 6, 1 April 1847, pp. 474-475 [Letter to Ed.].

To the Editor of the Pharmaceutical Journal.

Sir,--I shall be obliged if you will allow me, in reply to an observation in the last number of your journal, to state that the resemblance between the inhaler of Mr. Jeffreys, and that I have introduced for the vapour of ether, is not a coincidence, but is the result of my previous acquaintance with the former, and approval of it; and that I have never failed to mention the circumstance when saying or writing anything about the apparatus. The first notice of it in print appeared simultaneously in two medical journals, and contained the following words: "The instrument which Mr. Ferguson, of Smithfield, was making for him, was on the plan of the inhaler of Mr. Jeffreys, with some alterations and additions." (Med. Gaz. Jan. 22, p. 156, and Lancet, Jan. 23, p. 99.)

The object of the apparatus is to regulate the proportion of vapour in the air by regulating the temperature; and to effect this, I take advantage of the capacity for caloric which there is in two or three pints of water, and of the conducting power of metal of which the instrument is formed. The form I have adopted, is a matter of detail to enlarge the surface of ether exposed to the air.

The table you honoured me by publishing in the February number, is correct for ether, which is not free from alcohol, and boils at 104°. To make it correct for washed ether, which boils at 100° four degrees must be deducted; for instance, for 40° read 36°, and so on, and for washed ether deprived of its water by potash, and boiling at 98°, six degrees must be deducted. As I have stated elsewhere, I made use in constructing that table, of the formula for the elastic force of the vapour of ether, by Dr. Ure, in his paper on Heat, in the Philosophical Transactions for 1818; having ascertained by experiments, that it could be used with correctness for that purpose.

I remain, Sir, your obedient servant,

John Snow, M.D.

54, Frith Street, Soho, March 5th, 1847.

[We regret the observation we made last month, which, from Dr. Snow's statement, appears to have been erroneous.--Ed.]

Return to John Snow Publications

Return to John Snow Publications

25. "A lecture on the inhalation of vapour of ether in surgical operations"

25. "A lecture on the inhalation of vapour of ether in surgical operations"

Source: Snow, John. Lancet 1, 29 May 1847, pp. 551-54.

By John Snow, M.D.,

Lecturer on Forensic Medicine.

If a medical man had been asked, this time last year, whether it were possible to perform a severe surgical operation without the patient's feeling or showing any sign of pain, he would have answered in the affirmative. Such occurrences have taken place in profound insensibility arising from injuries of the head. In a state of imminent suffocation, from inflammation of the windpipe, that tube has been cut open in the throat without the patient being sensible of what was done; and operations might be performed in the deep insensibility of apoplexy and of epilepsy, without the sufferers feeling them. But if any one had been asked last year, whether it would be safe and practicable to induce such a state of insensibility as would prevent the most serious surgical operations being felt, and that without any ill consequences, he would, I think, undoubtedly have considered it an impossibility. Sir Humphry Davy, indeed, nearly fifty years ago, expressed an opinion that nitrous oxide gas might probably be used to prevent pain during surgical operations, but the laughing gas, as it is called, continued to be inhaled in small quantities for amusement only, and the suggestion of Davy was unattended to, at least till recently; for it appears that it was in some measure by following out the researches of Sir Humphry Davy, that Dr. Jackson was led to the recent brilliant, important, and most valuable discovery.

The inhalation of ether for the prevention of pain during surgical operations, was, as all are aware, introduced by Drs. Jackson and Morton, of Boston, U.S., at the end of last year. Another medical man, indeed, in America, is claiming the merit of the discovery, but a little time, no doubt, will suffice to decide to whom the merit is due, or how it should be apportioned. The only way in which I can exhibit the influence of ether on the present occasion, is on animals; they show the effects of it, however, in a very striking manner, and will illustrate what I have to say afterwards.