Stream 3- The "Grand Experiment"

d: The "Grand Experiment"

GRAND EXPERIMENT OF 1854

During Snow's life, London experienced cholera epidemics in 1831-32, 1848-49 and 1853-54. The Broad Street Pump outbreak and the "Grand Experiment" both occured during the 1853-54 epidemic.

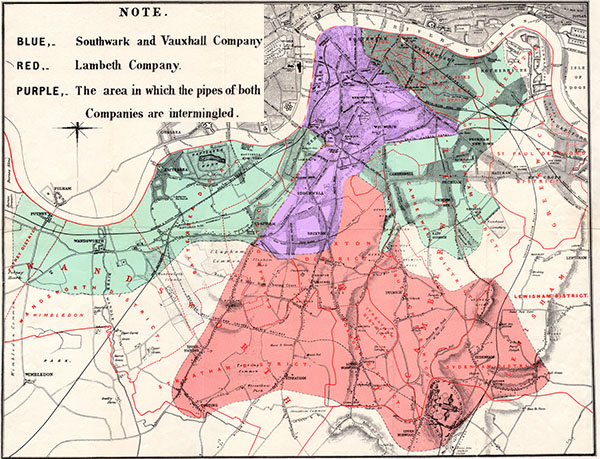

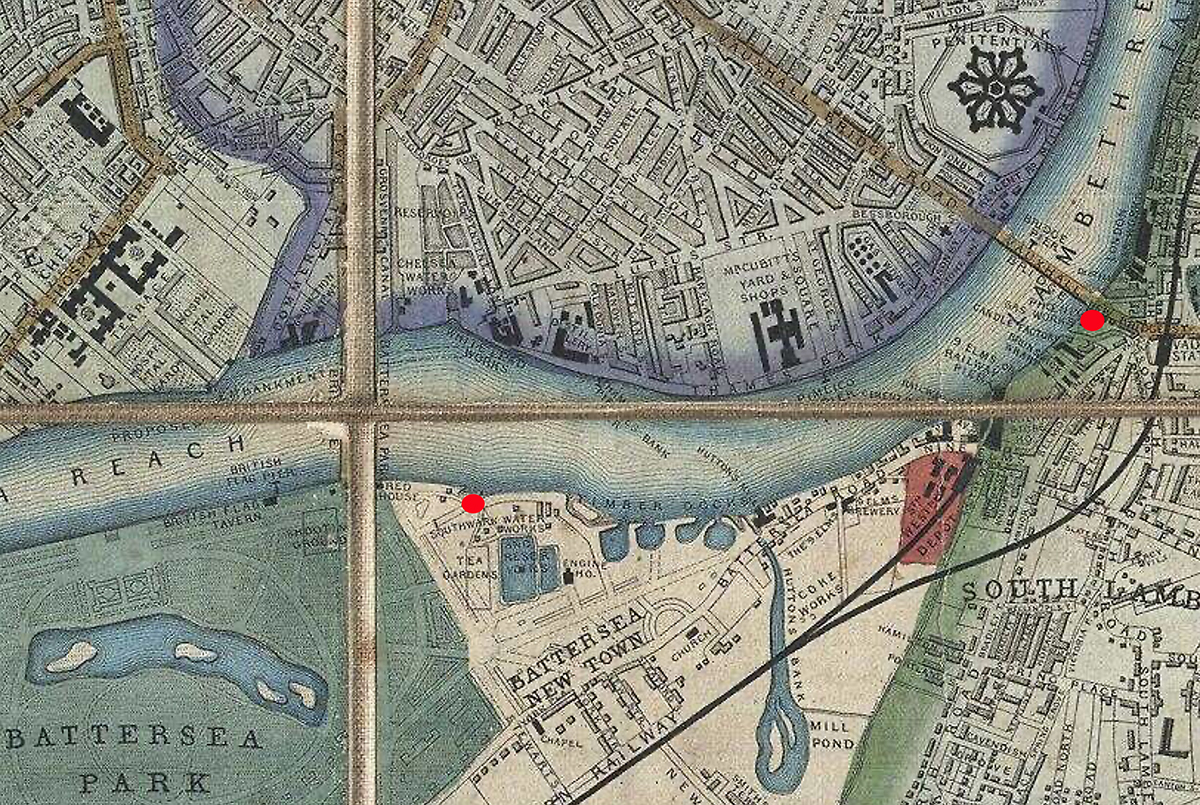

John Snow fully describes the "Grand Experiment" in part 3 of his book, On the Communication of Cholera, second edition (1855). He wrote of wanting to test the hypothesis that cholera was associatd with consuming clean versus contaminated River Thames water. Opportunity availed when one water company moved both its facilities and inlet up river while the other stayed in the same down river location, both still piping water to London households south of the River Thames. In his description, Snow focuses on a region of London where two water companies serviced the same general area, present in Map 2 as "purple." Yet the map had fadded with "blue" appearing as green, and "purple" appearing as a dull darkened red.

Map 2 (modified)

To clarify the following introductory words by Snow, the area where the Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company and the Lambeth Water Company had "intermingled" household customers is shown above in purple in modified Map 2.

"Throughout the greater part of Lambeth and Southwark, the whole of Newington, and a part of Camberwell, however, the supply of the two companies above mentioned is actually intermixed, the pipes of both companies going down the same streets, in consequence of the active competition which once existed between three water companies, two of which have since amalgamated and come to an agreement with the other — the Lambeth company. Observing, therefore, when the cholera returned in 1854, that there was the same advantage in favour of the districts partly supplied with water from Thames Ditton [an up-river location where River Thames water was purer], I determined to make an inquiry, the idea of which I had previously entertained. It was obvious that, if the diminished mortality depended on the improved supply of water, the benefit of the whole diminution would be enjoyed by the inhabitants of houses having this supply, whilst the population receiving impure water would suffer as much as that of the districts which received the same water, and no other. This point could be determined by ascertaining the water supply of every house in which a fatal attack of cholera might occur. After commencing the inquiry I found that the circumstances were calculated for affording even more conclusive evidence than I had anticipated. The pipes of the two water companies not only passed down all the streets, but into nearly all the courts and alleys. A single house often had a different supply from that on either side. Each water company supplied alike both rich and poor, and thus there was a population of 300,000 persons, of various conditions and occupations, intimately mixed together, and divided into two groups by no other circumstance than the difference of water supply. One group supplied with water contaminated, to a large extent, with the sewage of London, and the other receiving a supply altogether free from such impurity."

Snow goes on to describe the test he used to confirm which company supplied each household, finding that many households did not maintain good records.

"I took great care to ascertain the nature of the water supply correctly in every instance. I did not rest content with the mere reply of the resident, or the appearance of the water, without other evidence, such as the production of the receipt for the water rate. I was also assisted very much by the application of a chemical test to the water, for throughout all the dry weather, which lasted whilst my inquiries were being made, a mixture of sea water extended further up the Thames than usual, and the water of the Southwark and Vauxhall Company contained nearly forty grains of common salt per gallon, whilst that of the Lambeth Company contained only 0.95 of a grain. These analyses were verified in numerous cases where the source of the water could be proved clearly by other evidence."

Source: Snow, John, On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, second edition (1855).

The Makings of a Natural Experiment

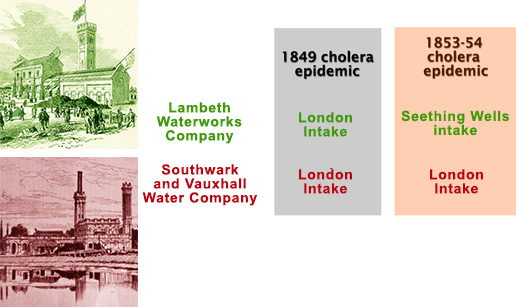

Hence two water companies supplied the same neighborhoods with water, with one company having moved to a fresh water site while the other remained in a polluted site. During the 1849 epidemic, the water of both companies was drawn from the same contaminated region of River Thames in London and the death rates among their consumers were similar. When cholera reappeared in 1853-54, however, the exposure to polluted water had changed. One company had moved upriver to Seething Wells while the other remained in place, establishing the basis for a natural experiment.

Of the unusual natural situation, Snow wrote (as mentioned above in the introduction):

"The experiment, too, was on the grandest scale. No fewer than three hundred thousand people of both sexes, of every age and occupation, and of every rank and station, from gentlefolks down to the very poor, were divided into two groups without their choice, and, in most cases, without their knowledge; one group being supplied with water containing the sewage of London, and, amongst it, whatever might have come from the cholera patients, the other group having water quite free from such impurity."

Source: Snow J. On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, 1855.

Source: Snow J. On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, 1855.

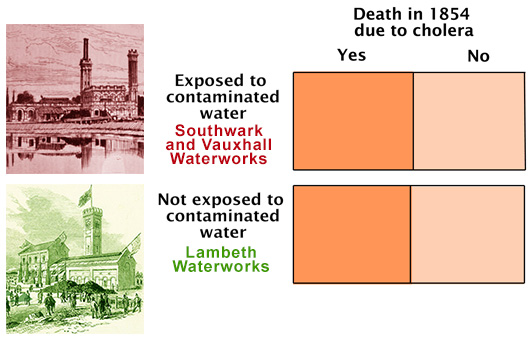

This was not a true experiment [but often referred to as a "natural experiment"] since Snow did not randomly allocated people into two groups, one exposed to contaminated water and the other not. Clearly, this would have been unethical and certainly illegal. Snow did, however, recognize that self-allocation in a near-randomized manner had taken place in a natural setting, and thus had taken advantage of this historical occurrence to test his hypothesis. He used the classic experimental design shown above to analyze his data and derive important conclusions for the eventual control of cholera.

Source: Snow J. On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, 1855.

MAPS AND IMAGES OF WATER COMPANIES

During the 1800's, the River Thames in the heart of London had long been viewed as a depository for human and animal waste, tasting and smelling vile on many occasions, causing outrage in the population. In a flashback to 1832 when cholera had come to London during the 1831-32 epidemic, prominent cartoonist George Cruickshank capture the feelings of the populace, focusing on the Southwark Water Works that supplied household water to many. His cartoon resonated as the voice of the people.

Aside - Cruickshank's Cartoon - Salus Populi Suprema Lex, 1832

Aside - Cruickshank's Cartoon - Salus Populi Suprema Lex, 1832

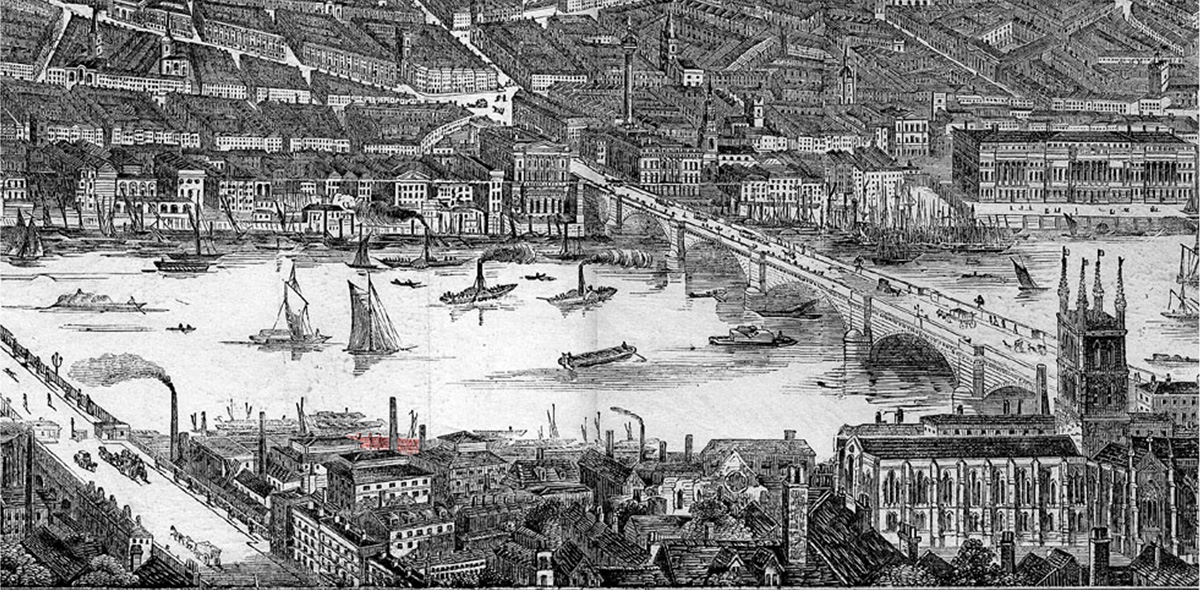

During the 1831-32 cholera epidemic prior to John Snow's arrival in London, llustrator George Cruikshank drew Salus Populi Suprema Lex, a Latin phrase that means "the welfare of the people is the supreme law." The setting is mid-day in the River Thames by the original Southwark Water Works, focusing on the company's poluted water inlet, then sending water out to London customers. As Cruickshank notes along top and bottom margins of the illustration, the tide of the River Thames is at low water (i.e., less dilution of pollutants) near the London Bridge, which appears in the background. He also writes, "hail Long-expected days that Thames's glory to the stars shall rise," suggesting future hope. Putrid smells emanating from the River Thames caused much uproar.

Twenty-three years would pass before Dr. John Snow would conduct the 1854 "grand experiment" comparing households exposed to contaminated water coming from the then-united Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company, with households receiving cleaner water from the Lambeth Water Company, moved earlier up river far away from the pollution, serving "unexposed" households consuming cleaner water. Many people at the time believed the "miasmatic theory" that noctious smells were causally associated with cholera, and the river certainly smelled and made people feel sick, including with cholera, recently arrived in 1831-32.

Continued Aside - BACKGROUND

Continued Aside - BACKGROUND

In a continued flashback, the Southwark Water Company started in 1770 as the The Borough Waterworks Company with Borough being an alternative for the more common Southwark. The company supplied river water to a nearby brewery and to the population that lived between the London and Southwark Bridges over the River Thames. The tidal river often smelled bad and the water intended for human consumption was reputed to be of poor quality.

In 1822, the Borough Waterworks Company purchased the rights to a neighboring water company and renamed itself as the Southwark Water Company, often referred to by Londoners as the Southwark Water Works.

The panorama shown below was created in 1844 but published in early 1845, just before the Southwark Water Company (shown below in red) was to change names once more. The panorama view is looking north across the River Thames, with the Southwark Bridge on the left and the London Bridge (in the background of Cruikshank's illustration) on the right.

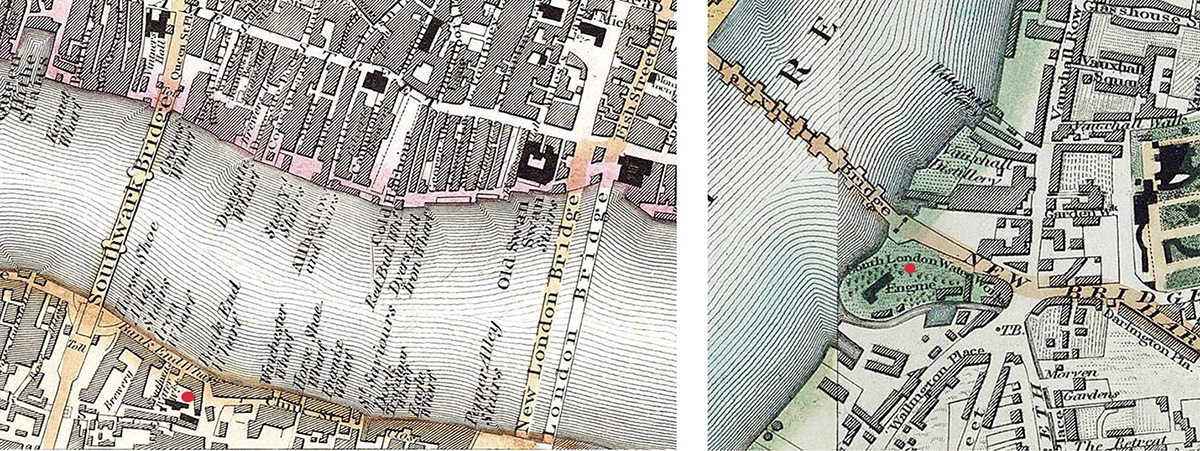

In 1845, thirteen years after the Cruickshank's cartoon had appeared, the Southwark Water Company merged with the South London Water Works at Vauxhall Bridge (see two red dots below in 1830 map), to become the Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company. That same year, the combined company moved to Battersea, up river, but still in the heart of London.

By 1852, as seen with the two red dots in Davies 1852 Case map below, Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company was well established (but still erroneously listed as "Southwark Water Works") by Battersea Park, and the former site of the Vauxhall Water Company at the base of the Vauxhall Bridge had become the Phoenix Gas Works.

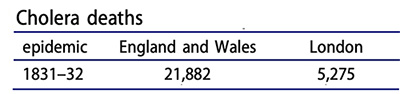

Arrival of Cholera, 1831-32

A new cholera epidemic came to England and Wales in 1831-32, terrifying the population. In London, cholera lead to the death of an estimated 5,275 people. Doctors were unfamiliar with the disease, not knowing how it spread nor of a suitable cure. The rapid onset of symptoms such as diarrhea, nausea and vomiting resulted in dehydration from fluid loss, lethargy, erratic heartbeat, sunken eyes and dry and shrivelled skin with a characteristic bluish tinge.

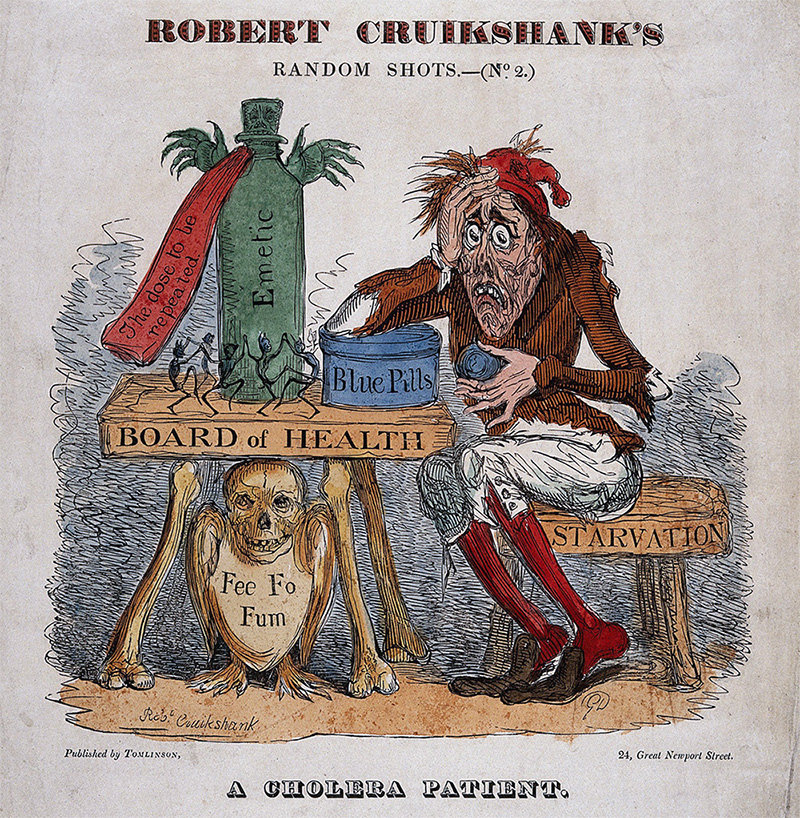

At the same time, with much uncertainty in how to prevent or treat cholera, the Cruikshank brothers continued to touch the public with their illustrations. In 1832, George Cruikshank (1792-1878) focused on prevention, with Salus Populi Suprema Lex (see above), drawing attention to polluted water. Medical practitioners were also unspared, coming forth with many suggestions but no effective therapies. The plight of a cholera patient was drawn at the same time by older brother Robert Cruikshank (1789-1856), documenting a confused patient, not knowing what to do or what to take. As an aside, "Fee Fo Fum" comes from an early version of an old English fairy tail, "Jack and the Beanstalk" with the full historic lyric being: "Fee, fau, fum, I smell the blood of an English man, be he alive, or be he dead, I'll grind his bones to make my bread."

Yet, the sanitation movement in London was underway. Cholera, thought by many, was associated with poor sanitary standards and crowding, especially among the impoverished segments of the population. Prevention programs promoted cleaning, drainage and ventilation. The sanitationists held as true the miasma theory, believing that diseases such as cholera were caused by the presence in the air of a miasma, a poisonous vapour in which were suspended particles of decaying matter, accounting for the foul smells.

When George Cruikshank in 1832-33 drew Salus Populi Suprema Lex and Robert Cruikshank also in 1832 in The Cholera Patient, they touched the prevailing social anxiety with their popular illustrations. It was not until many years later that the contagion theory would gain support, spurred on by energetic and independent minded Dr. John Snow some two decades later with his epidemiological investigations (notably the Broad Street Pump outbreak and the "Grand Experiment," and his many lectures and professional writings.

Sources

Cruikshank, George. Salud Populi Suprema Lex, Published by Samuel Knight, London, England, 1832-33.

Cruikshank, Robert. The Cholera Patient in Random Shots (No 1), A Cholera Doctor, 1832.

Davenport, RJ et al. Cholera as a ‘sanitary test’ of British cities, 1831–1866. The History of the Family, 24 (2), 404–438, 2019.

Davies, BR. Davies Case Map or Pocket Map of London, England, 1852.

Greenwood C and Greenwood J.Greenwood Map of London, 1830.

Panorama of the River Thames in 1845 given with The Illustrated London News. The Illustrated London News, 198, Strand, London, January 11, 1845.

Science Museum, Cholera in Victorian London, July 30, 2019.

Tatar, Maria. "Jack and the Beanstalk". The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales. New York: W. W. Norton and Co. pp. 131–144, 2002.

End of Aside - Forward to 1854

End of Aside - Forward to 1854

As years went by, the water companies changed names and owners, but the problems remained. When Dr. John Snow came on the scene, the Southwork Water Works had become the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, but the smells were still there.

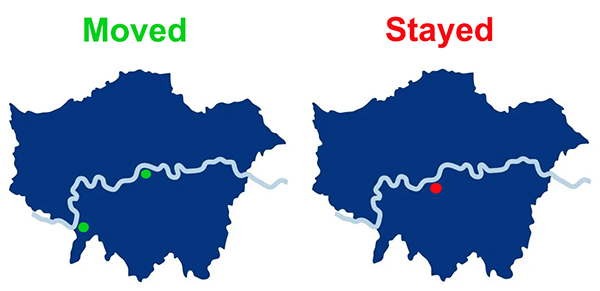

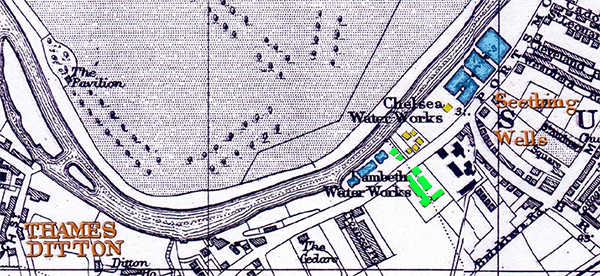

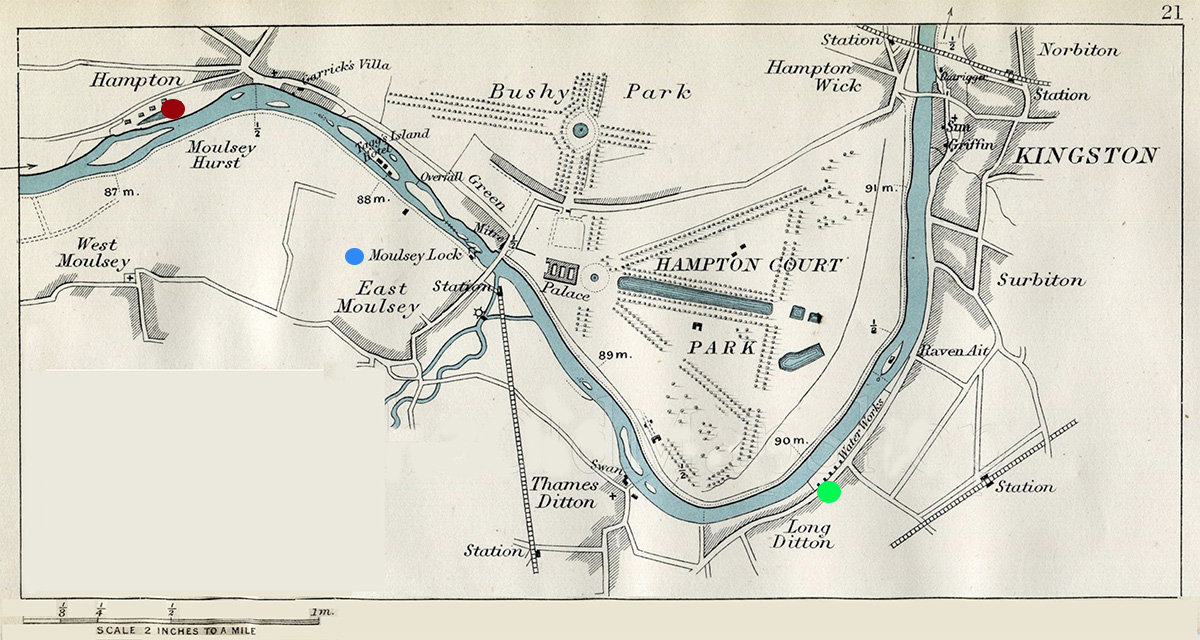

In Part 3 of his book, John Snow published Map 2 which presented the water distribution of the Lambeth company and the Southwark and Vauxhall company. Shown here is a section of Snow's Map 2 with the location of the two water companies prior to Snow's "grand experiment," the Lambeth (green dot) and the Southwark and Vauxhall company (red dot).

The "Grand Experiment" of 1854 was made possible when the Lambeth Company in 1852 moved up-river to Seething Wells by Thames Ditton, free of pollution, while the Southwark and Vauxhall Company remained down-river near Battersea Park in the polluted section of River Thames. The Lambeth Company continued to pipe water from its new clearner locaton to its previous household customers.

Lambeth Water Company

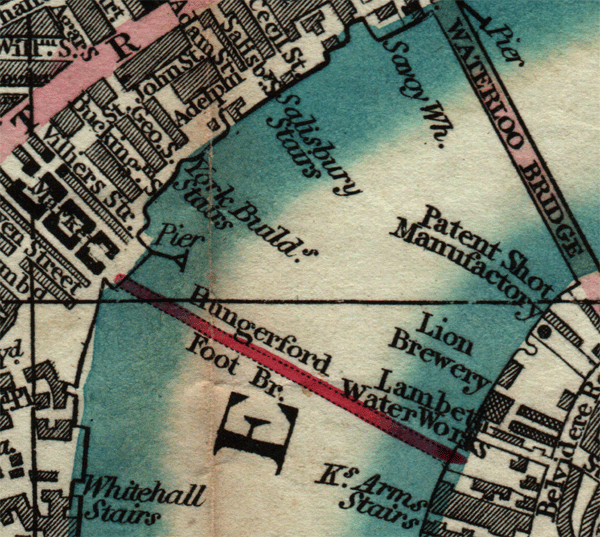

Below is the Lambeth Water Company site before the 1852 move. It sat next to the Hungerford Bridge in London, next door to the Lion Brewery (which had earlier relocated from the Broad Street pump area), down a short ways from the Waterloo Bridge.

Source: G.F. Cruchley. Cruchley's New Plan of London improved to 1846, Cruchley Map Seller and Publisher, 1846

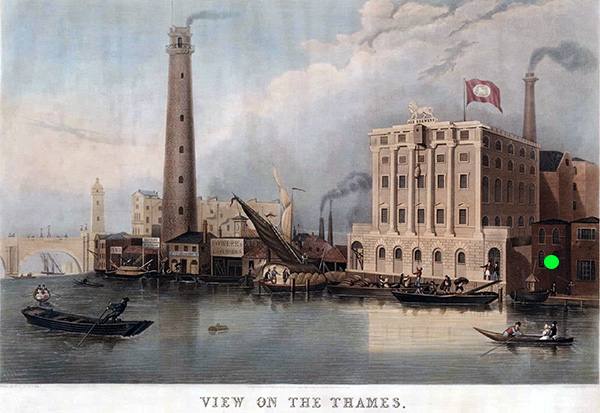

The painting below by artist John O'Connor partially shows the Lambeth Water Works to the right of the Lion Brewery (see green dot). The brewery building with the lion on top and flowing red flag was designed by Francis Edwards, and built in 1836 by James Goding.

Source: O'Connor, John (1830-1889). View of the River Thames, published by John Moore, corner of West Street, St. Martins Lane, London, 1875.

At right is the location after the 1852 move to the Seething Wells neighborhoood by Thames Ditton, with the Lambeth Company (in green) now located in the unpolluted upriver section of River Thames near the Chelsea Water Works, a different water company unrelated to Snow's "Grand Experiment." Shown in blue are the waterworks reservoirs, some shared with the Chelsea company.

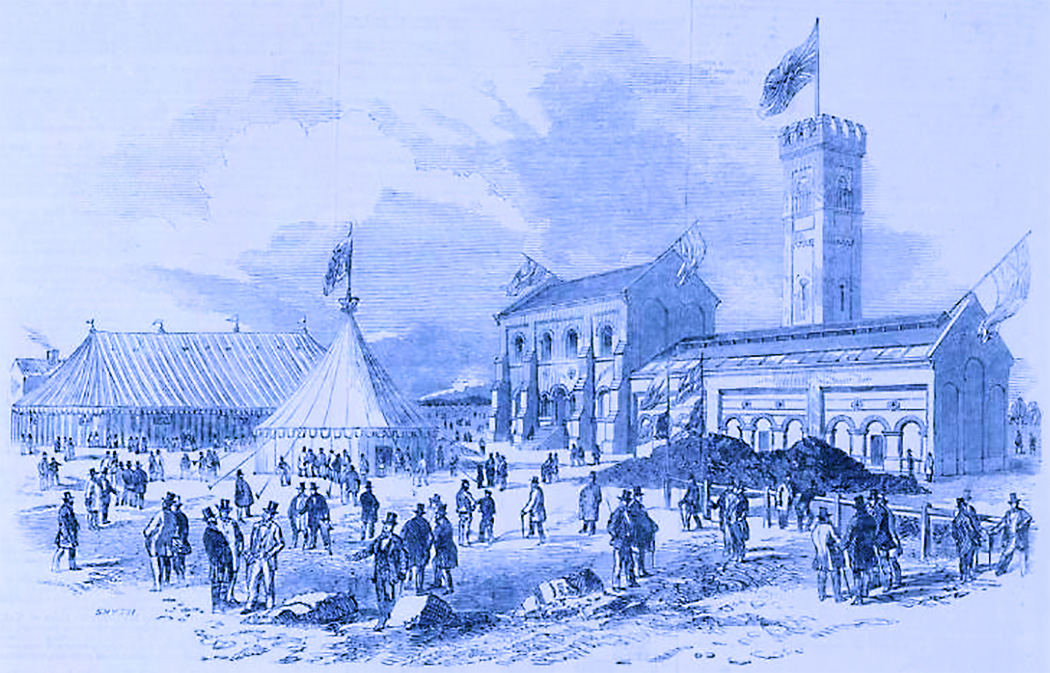

The grand opening of the new location of the Lambeth Company was featured in The Illustrated London News of April 3, 1852. The new facility via an inlet pipe gathers water from the nearby River Thames to be held in local filtration reservoirs. The company then used four massive steam engines to pump ten million gallons daily from the filtration beds to two large holding reservoirs near London at Brixton and Streatham Hill. From there, the water was piped to customers in the city.

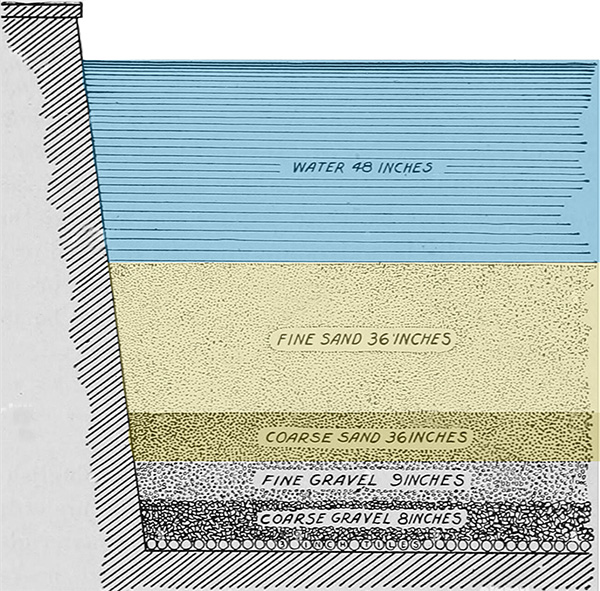

The large filtration reservoirs in Seething Wells (see below) were newly designed by notable company engineer James Simpson (1799–1869) to have the river water pass down through four levels of purification. The top stratum was comprised of fine sand, the next of course sand, followed by a third of fine gravel, and finally, a fourth stratum of course gravel. The purified water then flows along several brick channels at the bottom of the reservoirs into a well. In the final step, the clean well water was pumped into a supply pipe flowing on to large holding reservoirs at Brixton and Streatham near London, where it was distributed to new and present tenants, including the intermingled households for the "Grand Experiment" shown in modfied Map 2 at top.

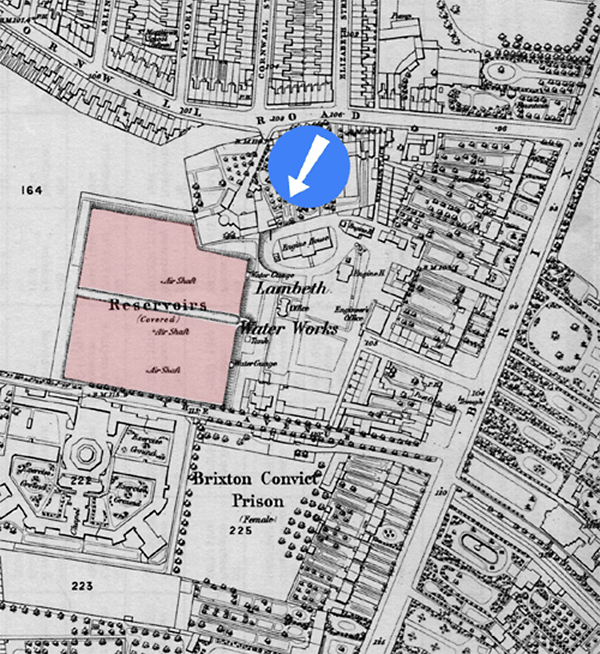

Brixton Reservoir

In 1834, The Lambeth Waterworks Company built a new headquarters located in the southern region of London, along with another reservoir in Brixton, in addition to the Streatham Hill reservoir built two years earlier. Adjacent to the company was the Brixton Prison, built in 1819-20. Also in 1834, the The Lambeth company in 1836 had sold some of their land to the prison, which at that time was in private hands. Later in the 1853, the prison was sold to the government.

Source: Old Ordnance Survey Maps - Brixton and Herne Hill, 1870.

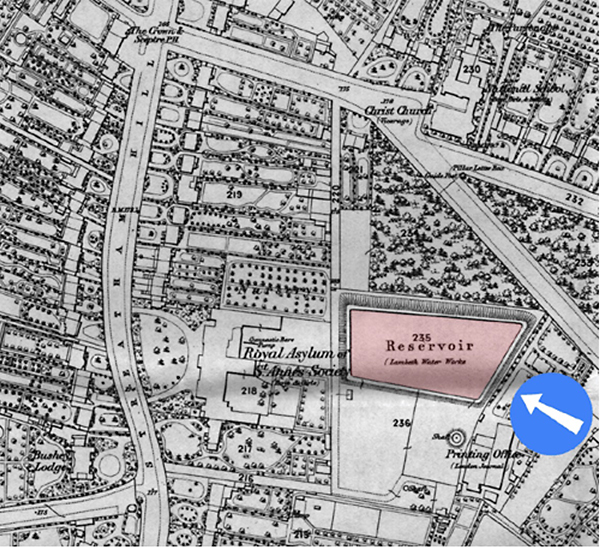

Streatham Hill Reservoir

The 1870 Old Ordnance Survey map shows the London area reservoir of the Lambeth Waterworks Company. It was built in 1832. The reservoir was situated in the frontier of London, rural but with pockets of development. The company reservoir was next to the Royal Asylum of St. Anne's Society, built in 1829-30 and still used as a residential school in 1870.

Both sets of reservoirs in the London area received pumped water from the new up-river Seething Wells location of the Lambeth Water Company starting in 1852, then distributed to customers in London.

Source: Old Ordnance Survey Maps - Streatham Hill and Tulse Hill, 1870.

Start of the "Grand Experiment"

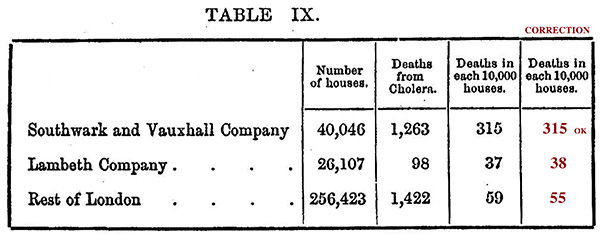

On July 8, 1854, John Snow and his assistant started gathering cholera mortality data on the interminggled houses in the overlapping region receiving water from the Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company and the Lambeth Water Company (i.e., purple area in modified Map 2 above). The full details are included in Part 3 of Snow's 1855 book. Table IX best describes his findings at the seven week mark of the study (included are corrections for two minor math errors).

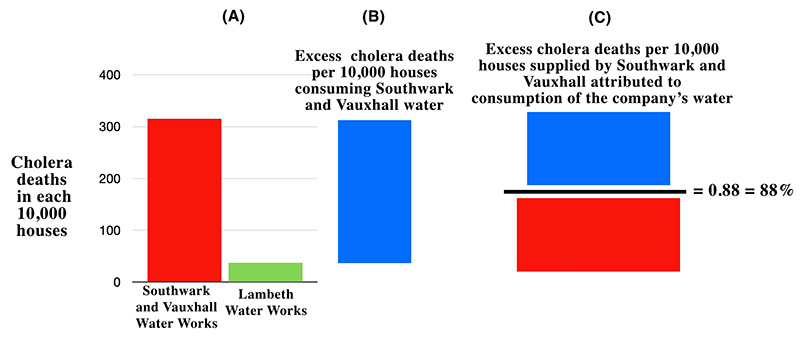

Snow wrote of his findings, comparng the cholera mortality numbers 315, 37 and 59 deaths per 10,000 houses, respectively for those supplied by the two water companies and for the rest of London: "The mortality in the houses supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company was therefore between eight and nine times as great as in the houses supplied by the Lambeth Company; and it will be remarked that the customers of the Lambeth Company continued to enjoy an immunity from cholera greater than the rest of London which is not mixed up as they are with the houses supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company."

A more standard analysis employed by current policy-oriented epidemiologists derives excess mortality attributed to a factor of interest (i.e., attributable risk measures). Rather than commenting about elevation in risk, the corrected data can be rearranged to better address the policy implications of the findings. As shown in the figure at left, the cholera deaths per 10,000 houses are first compared in a graph, then rearranged with calculations.

Clearly in (A), Southwark and Vauxhall supplied houses had a much higher cholera mortality than Lambeth supplied houses. The differences between the "exposed" and "unexposed" houses is presented in (B), which shows the amount of excess cholera mortality experienced by the Southwark and Vauxhall customers, as compared to those who used Lambeth Company water. In (C), the excess cholera mortality in the Southwark and Vauxhall group is divided by the total cholera mortality in the same group, which, using Snow's corrected findings, is 0.88. To ease understanding, proportions are typically muliplied by a hundred to derive a percentage, or in this instance, 88 percent. That is, persons residing in the same neighborhood that receive drinking water from the Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company could have reduced their household cholera death occurrence by 88 percent if only they had switched their water source to the Lambeth Water Company. This formulation is a powerful tool for public persuation, likely better than the mortality ratio of "between eight and nine times as great," as used by Snow.

Of course, the excess mortality measure assumes that the "Grand Experiment" was an actual experiment comprised of two sets of houses with near equal risk of choldera death independent of their water company. Such equivalency is created by epidemiologists and statisticians with random allocation of subjects to one group or another, which in Snow's setting could not have been done since customers voluntarily decided which company they wanted to support via personal finance and self-allocation.

Finally, Snow's research points to a close association between the water source and cholera, but not necessarily a causal association. Decades later when Vibrio cholerae was finally discovered, the causal nature of Snow's findings became evident, adding another milestone to his reputation as the father of modern epidemiology.

POST "GRAND EXPERIMENT"

Faraday and the Sanitation Movement

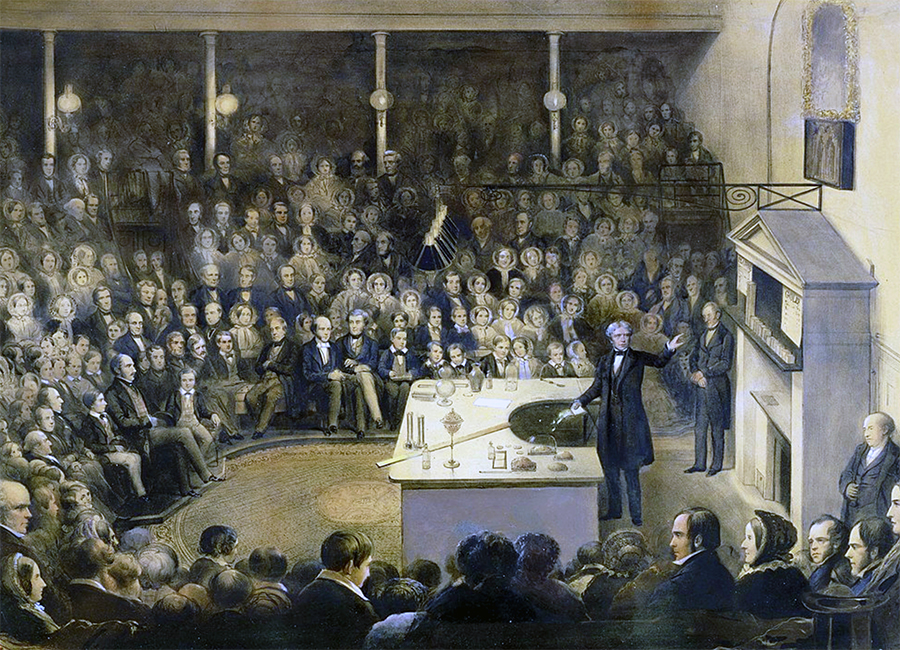

Michael Faraday (1791-1867, at right) was a prolific and highly regarded scientist during Snow's time in London, employed as a professor of chemistry at the Royal Institution of London. Yet his scientific interests and accomplishments were much wider than chemistry. Faraday was very popular, and attracted extensive attention. Almost annually between 1827 and 1860, he gave a Christmas lecture at the Royal Institution of London for young people, inspiring them and others to become interested in science (see below in 1856).

While there is no indication that Faraday and Snow associated with one another, they did share an interest in the sanitation movement, notably the pollution of the River Thames.

In 1855 while Snow's book, On the communication of cholera was about to be published, Faraday wrote a letter to the Times on July 7, 1855 which caused quite a stir. It was entitled, "Observations on the Filth of the Thames." and reads as follows:

SIR,

I traversed this day by steam-boat the space between London and Hangerford Bridges between half-past one and two o'clock; it was low water, and I think the tide must have been near the turn. The appearance and the smell of the water forced themselves at once on my attention. The whole of the river was an opaque pale brown fluid. In order to test the degree of opacity, I tore up some white cards into pieces, moistened them so as to make them sink easily below the surface, and then dropped some of these pieces into the water at every pier the boat came to; before they had sunk an inch below the surface they were indistinguishable, though the sun shone brightly at the time; and when the pieces fell edgeways the lower part was hidden from sight before the upper part was under water. This happened at St. Paul's Wharf, Blackfriars Bridge, Temple Wharf, Southwark Bridge, and Hungerford; and I have no doubt would have occurred further up and down the river. Near the bridges the feculence rolled up in clouds so dense that they were visible at the surface, even in water of this kind.

The smell was very bad, and common to the whole of the water; it was the same as that which now comes up from the gully-holes in the streets; the whole river was for the time a real sewer. Having just returned from out of the country air, I was, perhaps, more affected by it than others; but I do not think I could have gone on to Lambeth or Chelsea, and I was glad to enter the streets for an atmosphere which, except near the sink-holes, I found much sweeter than that on the river.

I have thought it a duty to record these facts, that they may be brought to the attention of those who exercise power or have responsibility in relation to the condition of our river; there s nothing figurative in the words I have employed, or any approach to exaggeration; they are the simple truth. If there be sufficient authority to remove a putrescent pond from the neighbourhood of a few simple dwellings, surely the river which flows for so many miles through London ought not to be allowed to become a fermenting sewer. The condition in which I saw the Thames may perhaps be considered as exceptional, but it ought to be an impossible stat, instead of which I fear it is rapidly becoming the general condition. If we neglect this subject, we cannot expect to do so with impunity; nor ought we to be surprised if, ere many years are over, a hot season give us sad proof of the folly of our carelessness.

I am, Sir,

Your obedient servant,

M. FARADAY.

Royal Institution, July 7, 1855

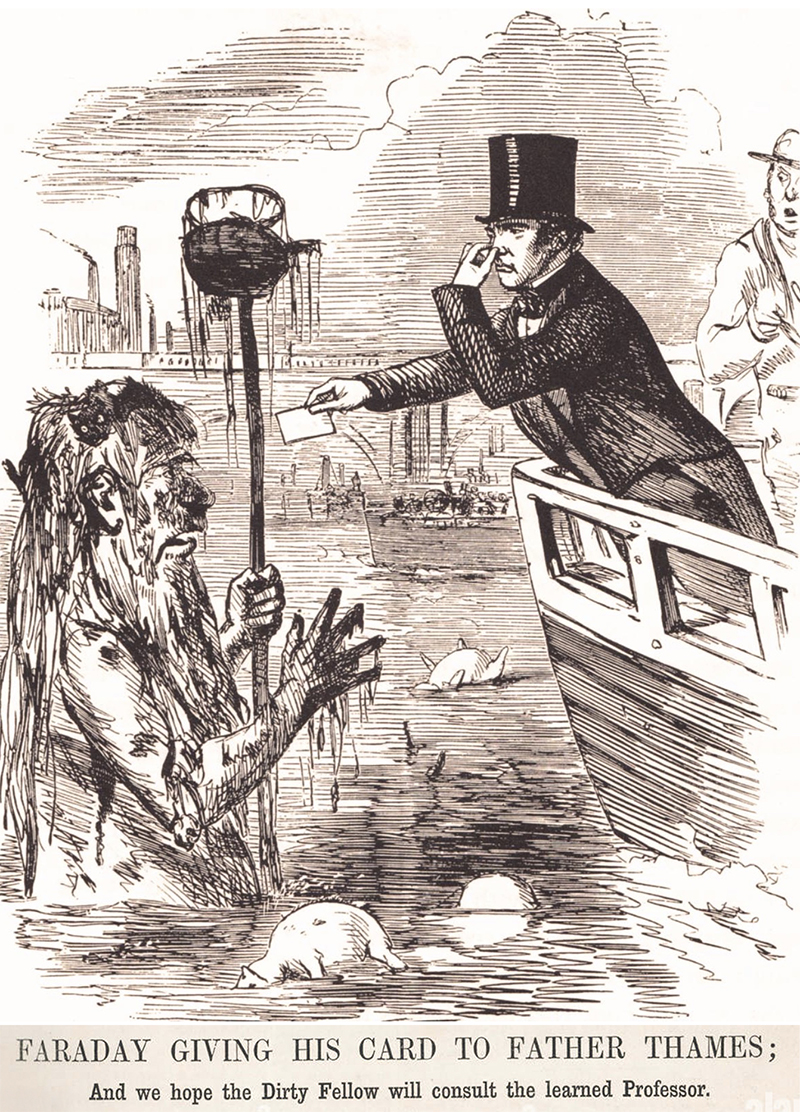

British cartoonist John Leech (1817-1864, above) wasted no time, depicting popular professor Faraday in the July 21, 1855 edition of Punch magazine, handing his calling card with held nose to filthy Father Thames, the symbol of the polluted River Thames.

Later in 1855 when John Snow's book appeared, it barely caused a ripple, not like the castigation of the smelly river that Faraday and Leech put forth, focusing on something that people clearly understood.

In contrast, Snow paid his publisher £200 for the printing, producing only 300 copies of his masterful 1855 book. Even then, only 56 copies were actually sold.

Clearly, the medical community and certainly the general public still maintained their skepticism, most favoring the "miasma theory," personified by the smelly River Thames.

Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company

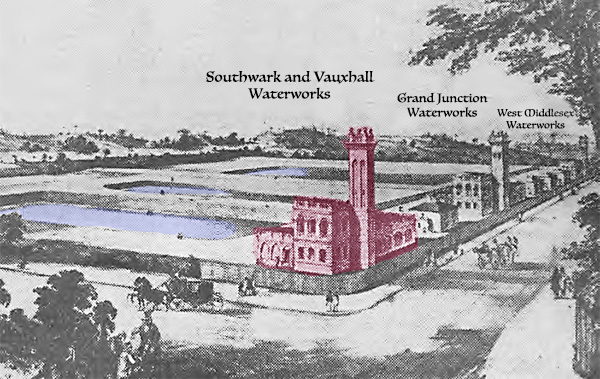

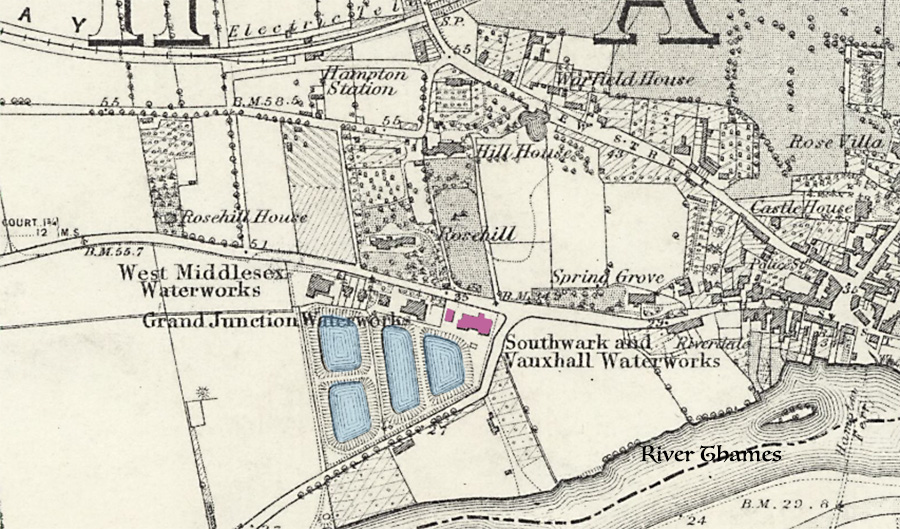

In 1855 following the "Grand Experiment", Southwark and Vauxhall Waterworks finally moved its facility and inlet pipe to the Hampton area (red dot below), above the Moulsey Lock of the River Thames (blue dot). The move was further upriver than the Lambeth Water Company in the Seething Wells neighborhood of Thames Ditton (green dot). Accompanying Southwark and Vauxhall were two other water companies, Grand Junction Waterworks and Middlesex Waterworks, that shared the reservoirs

Source: Henry Taunt Antique Map, The River Thames, East Molesey, Bushy Park, Hampton Court, Thames Ditton, Surbiton, Kingston, Surrey, London, 1873.

Source:Ordnance Survey map, c1864.