While the field of epidemiology is not widely thought about by younger people, perhaps not thinking of it at all or mistaking it for studies of the epidermal layer of skin. Yet the tale of John Snow offers a welcome introduction to epidemiology if presented by effective authors and illustrators, understanding the interests of children eager to expand their horizons.

Included here are two writings featuring John Snow. The first is an article in Cricket Magazine, a world leader in offering fiction and nonfiction to children aged 9 to 14 years. The second is more advanced in style, submitted in the National History Day of 2009 competition among high school students by gold metal winner Laura Ball of Wauwatosa, Wisconsin. Also incuded at the beginning or each section are several books on John Snow for interested readers in the respective age groups.

The Younger Group

Evidence!: How Dr. John Snow Solved the Mystery of Cholera by Deborah Hopkinson (Author), Nik Henderson (Illustrator), 2024 (4-8 years)

The Great Trouble: A Mystery of London, the Blue Death, and a Boy Called Eel by Deborah Hopkinson, 2015. (10-12 years)

Poison at the Pump by Sheila Seifert and Chris Brack, 2020 (7-12 years)

Source: Cricket 31(3), pp. 23-31, Nov. 2003 (reprinted by permission of the author and Cricket Magazine, November 2003; text (c) 2003 by Kathleen Tuthill, artwork(c) 2003 by Carus Publishing Company).

By Kathleen Tuthill, Illustrated by Rupert Van Wyk

British doctor John Snow couldn’t convince other doctors and scientists that cholera, a deadly disease, was spread when people drank contaminated water until a mother washed her baby’s diaper in a town well in 1854 and touched off an epidemic that killed 616 people.

Dr. Snow, an obstetrician with an interest in many aspects of medical science, had long believed that water contaminated by sewage was the cause of cholera. Cholera is an intestinal disease than can cause death within hours after the first symptoms of vomiting or diarrhea. Snow published an article in 1849 outlining his theory, but doctors and scientists thought he was on the wrong track and stuck with the popular belief of the time that cholera was caused by breathing vapors or a “miasma in the atmosphere”.

The first cases of cholera in England were reported in1831, about the time Dr. Snow as finishing up his medical studies at the age of eighteen. Between 1831 and 1854, tens of thousands of people in England died of cholera. Although Dr. Snow was deeply involved in experiments using a new technique, known as anesthesia, to deliver babies, he was also fascinated with researching his theory on how cholera spread.

In the middle 1800s, people didn't have running water or modern toilets in their homes. They used town wells and communal pumps to get the water they used for drinking, cooking and washing. Septic systems were primitive and most homes and businesses dumped untreated sewage and animal waste directly into the Thames River or into open pits called "cesspools". Water companies often bottled water from the Thames and delivered it to pubs, breweries and other businesses.

Dr. Snow believed sewage dumped into the river or into cesspools near town wells could contaminate the water supply, leading to a rapid spread of disease.

In August of 1854 Soho, a suburb of London, was hit hard by a terrible outbreak of cholera. Dr. Snows himself lived near Soho, and immediately went to work to prove his theory that contaminated water was the cause of the outbreak.

"Within 250 yards of the spot where Cambridge Street joins Broad Street there were upwards of 500 fatal attacks of cholera in 10 days," Dr. Snow wrote "As soon as I became acquainted with the situation and extent of this irruption (sic) of cholera, I suspected some contamination of the water of the much-frequented street-pump in Broad Street."

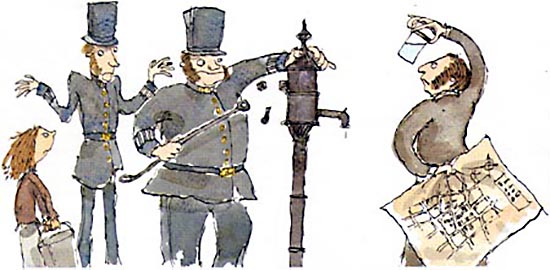

Dr. Snow worked around the clock to track down information from hospital and public records on when the outbreak began and whether the victims drank water from the Broad Street pump. Snow suspected that those who lived or worked near the pump were the most likely to use the pump and thus, contract cholera. His pioneering medical research paid off. By using a geographical grid to chart deaths from the outbreak and investigating each case to determine access to the pump water, Snow developed what he considered positive proof the pump was the source of the epidemic.

Besides those who lived near the pump, Snow tracked hundreds of cases of cholera to nearby schools, restaurants, businesses and pubs.

According to Snow's records, the keeper of one coffee shop in the neighborhood who served glasses of water from the Broad Street pump along with meals said she knew of nine of her customers who had contracted cholera.

A popular bubbly drink of the time was called "sherbet", which was a spoonful of powder that fizzed when mixed with water. In the Broad Street area of Soho, that water usually came from the Broad Street pump and was, Snow believed, the source for many cases.

Snow also investigated groups of people who did not get cholera and tracked down whether they drank pump water. That information was important because it helped Snow rule out other possible sources of the epidemic besides pump water.

He found several important examples. A workhouse, or prison, near Soho had 535 inmates but almost no cases of cholera. Snow discovered the workhouse had its own well and bought water from the Grand Junction Water Works.

The men who worked in a brewery on Broad Street which made malt liquor also escaped getting cholera. The proprietor of the brewery, Mr. Huggins, told Snow that the men drank the liquor they made or water from the brewery's own well and not water from the Broad Street pump. None of the men contracted cholera. A factory near the pump, at 37 Broad Street, wasn't so lucky. The factory kept two tubs of water from the pump on hand for employees to drink and 16 of the workers died from cholera.

The cases of two women, a niece and her aunt, who died of cholera puzzled Snow. The aunt lived some distance from Soho, as did her niece, and Snow could make no connection to the pump. The mystery was cleared up when he talked to the woman's son. He told Snow that his mother had lived in the Broad Street area at one time and liked the taste of the water from the pump so much that she had bottles of it brought to her regularly. Water drawn from the pump on 31 August, the day of the outbreak, was delivered to her. As was her custom, she and her visiting niece took a glass of the pump water for refreshment, and according to Snow's records, both died of cholera the following day.

Snow was able to prove that the cholera was not a problem in Soho except among people who were in the habit of drinking water from the Broad Street pump. He also studied samples of water from the pump and found white flecks floating in it, which he believed were the source of contamination.

On 7 September 1854, Snow took his research to the town officials and convinced them to take the handle off the pump, making it impossible to draw water. The officials were reluctant to believe him, but took the handle off as a trial only to find the outbreak of cholera almost immediately trickled to a stop. Little by little, people who had left their homes and businesses in the Broad Street area out of fear of getting cholera began to return

Despite the success of Snow's theory in stemming the cholera epidemic in Soho, public officials still thought his hypothesis was nonsense. They refused to do anything to clean up the cesspools and sewers. The Board of Health issued a report that said,"we see no reason to adopt this belief" and shrugged off Snow's evidence as mere "suggestions."

For months afterward Snow continued to track every case of cholera from the 1854 Soho outbreak and traced almost all of them back to the pump, including a cabinetmaker who was passing through the area and children who lived closer to other pumps but walked by the Broad Street pump on their way to school. What he couldn't prove was where the contamination came from in the first place.

Officials contended there was no way sewage from town pipes leaked into the pump and Snow himself said he couldn't figure out whether the sewage came from open sewers, drains underneath houses or businesses, public pipes or cesspools.

The mystery might never have been solved except that a minister, Reverend Henry Whitehead, took on the task of proving Snow wrong. The minister contended that the outbreak was caused not by tainted water, but by God's divine intervention.

He did not find any such proof and in fact, his published report confirms Snow's findings. Best of all, it gave Snow the probable solution to the cause of the pump's contamination.

Reverend Whitehead interviewed a woman, who lived at 40 Broad Street, whose child had contracted cholera from some other source. The child's mother washed the baby's diapers in water which she then dumped into a leaky cesspool just three feet from the Broad Street pump, touching off what Snow called "the most terrible outbreak of cholera which ever occurred in this kingdom."

A year later a magazine called The Builder published Reverend Whitehead's findings along with a challenge to Soho officials to close the cesspool and repair the sewers and drains because "in spite of the late numerous deaths, we have all the materials for a fresh epidemic." It took many years before public officials made those improvements.

In 1883 a German physician, Robert Koch, took the search for the cause of cholera a step further when he isolated the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, the "poison" Snow contended caused cholera. The cholera epidemics in Europe and the United States in the 19th century ended after cities finally improved water supply sanitation.

The World Health Organization estimates 78 percent of the people in Third World countries are still without clean water supplies today, and up to 85 percent of those people don't live in areas with adequate sewage treatment, making cholera outbreaks an ongoing concern in some parts of the world.

Today, scientists consider Snow to be the pioneer of public health research in a field known as epidemiology. Much of the current

epidemiological research done at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention still uses theories such as Snows's to track the sources and causes of many

diseases.

The Older Group

The Ghost Map: The Story of London's Most Terrifying Epidemic--and How It Changed Science, Cities, and the Modern World by Steven Johnson, 2007.

The Medical Detective: John Snow, Cholera and the Mystery of the Broad Street Pump by Sandra Hempel, 2007.

Pandemic: Tracking Contagions, from Cholera to Coronaviruses and Beyond by Sonia Shah, 2017.

NOTE

The best reference book on John Snow by far is Cholera, Chloroform, and the Science of Medicine: A Life of John Snow by Peter Vinten-Johansen, Howard Brody, Nigel Paneth, Stephen Rachman and Michael Russell Rip (2003). A follow -up book, Investigating Cholera in Broad Street: A history in Documents by Peter Vinten-Johansen (2020), provides additional reference information.

WINNER OF NATIONAL HISTORY DAY 2009: THE INDIVIDUAL IN HISTORY

In 2009, over a half a million high school students across the country participated in the annual National History Day celebration, and addressed the theme for the year, namely “The Individual in History.”

The winner of the individual paper, senior division gold metal was Laura Ball of Wauwatosa, Wisconsin, a western suburb of Milwaukee, part of the Milwaukee metropolitan area. She had started her formal education in a Montessori School, but soon transferred to St. Jude’s’ Elementary in Wauwatosa. As a ninth grader she attended the University School of Milwaukee, and entered the National History Day writing contest on several occasions. Then 2009 came along in her junior year with the "Individual in History" theme. She became the national winner of the coveted gold medal with her paper, "Cholera and the Pump on Broad Street: The Life and Legacy of John Snow.” The paper was subsequently published in The History Teacher Vol. 43, No. 1, November 2009, pp. 105-119.

Cholera and the Pump on Broad Street: The Life and Legacy of John Snow

Laura Ball

Senior Division Historical Paper, National History Day 2009 Competition

After all, it really is all of humanity that is under threat during a pandemic.

- Dr. Margaret Chan, Director General of the World Health Organization

There is still a pump in the Golden Square neighborhood on what was once called Broad Street. It does not work, for it is merely a replica of the original, and like the original its handle is missing. It serves as a curiously simple monu ent to the events that took place over one hundred years ago, when the real pump supplied water to the Broad Street residents. In 1854, hundreds of these hapless locals dropped dead within days of each other as Soho experienced one of the most brutal outbreaks of cholera that London has ever seen.[1] Not even the most eminent physicians could say what caused the disease, or why it came and went as it did.

John Snow’s solution to the cholera crisis broke the medical conventions of his era, slowed the progress of a virulent intercontinental disease, and forever changed the way society confronts public health problems.

Cholera, The Blue Death

Cholera plagued civilization for many generations before John Snow’s break-through. Medical researchers confirm that cholera was present in India in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, though records of diseases with cholera-like symptoms extend back as far as the fifth century B.C. The first intercontinental surge, referred to as the First Pandemic, occurred from 1817 to 1823.[2] Following waterways, cholera spread from India to Syria, East Africa, and Japan, but did not enter Europe. The Second Pandemic brought cholera to mainland Europe and Britain, then across the Atlantic Ocean to New York and Montreal between 1826 and 1837. Nine years later, the Third Pandemic began, promptly ravaging John Snow’s area of southern London.

Microbiology has shown that cholera comes from a bacterium called Vibrio cholerae that enters the body through contaminated water or possibly food. The bacteria’s interference in the small intestine causes profuse diarrhea and vomiting. The consequent dehydration produces several distinctive symptoms. As the concentration of water in the bloodstream decreases, the blood becomes thick and tarlike. Capillaries rupture, which often turns the skin blue. The heart rate becomes irregular, and dehydrated limbs begin to shrivel. The nervous system, however, remains intact until the end, leaving the victim fully conscious of the pain. Without treatment, death occurs within days—or even hours—of the first symptoms.[3]

Before the days of modern technology, physicians knew little of cholera’s origins. Most of them believed that diseases such as cholera were caused by foul odors, or miasmas, in the atmosphere.[4] They also thought that cholera was, given the symptoms, fundamentally a condition of the blood rather than the digestive system.[5] These speculative conclusions led to a diverse spectrum of largely ineffective “remedies.” Public anxiety rose in proportion to the death toll. Britain established its first Board of Health, and scientific institutes offered monetary rewards for methods of preventing or curing cholera. For decades, nothing worked.

Enter John Snow.

John Snow, the Teetotaler

Despite his modest background, John Snow distinguished himself early in life as a bright boy with a special talent for mathematics. At the age of fourteen, he secured a medical apprenticeship with William Hardcastle in Newcastle-upon- Tyne. Snow’s tenure with Hardcastle exposed him to cholera patients for the first time during an outbreak in Killingworth in 1832.

Snow continued his studies in London and became a fully certified physician, receiving invitations to join the Westminster Medical Society (of which he later became president) as well as the Royal College of Physicians and the London Epidemiological Society (of which he was a founding member).[6] He devoted much of his time to the newly-developed field of anesthesiology, designing and constructing inhalers to dispense ether and chloroform more effectively with less risk of overdose. Although the concept of anesthesia originated in Boston, many modern practitioners regard John Snow as the world’s first professional anesthetist because he spent his career administering these new anesthetics to the general public.[7] The Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society declared him to be “more extensively conversant with its operation, and more successful in administering it, than any living person.”[8] He was even summoned to the palace to give chloroform to Queen Victoria during labor.[9]

John Snow was modest, industrious, and taciturn. He confounded the medical community with his decision to become a vegetarian and abstain from liquor. On occasion, he publicly advocated for temperance.[10] His friend, Benjamin Ward Richardson, wrote that “… he lived on an anchorite’s fare, clothed plainly, kept no company, and found every amusement in his science books, his experiments, and simple exercise.”[11] His lifestyle along with his work made him a controversial figure in Victorian England.

Snow versus Cholera

Snow’s interest in cholera, first piqued in Killingworth, did not resurface until 1849. He published a pamphlet speculating that cholera must be, fundamentally, a digestive disease, because the initial symptoms were vomiting and diarrhea. This premise led Snow to conclude that the contagion entered and left the body through the oral-fecal route, and therefore that cholera was caused by consuming a contaminated substance.[12] His argument contradicted the multitude of doctors who believed that cholera was essentially a disorder of the blood. Indeed, Snow acknowledged his unorthodoxy in the pamphlet: “It is quite true that a great deal of argument has been employed on the opposite side, and that many eminent men hold an opposite opinion.”[13] However, this awareness would not prevent him from pursuing his own theory.

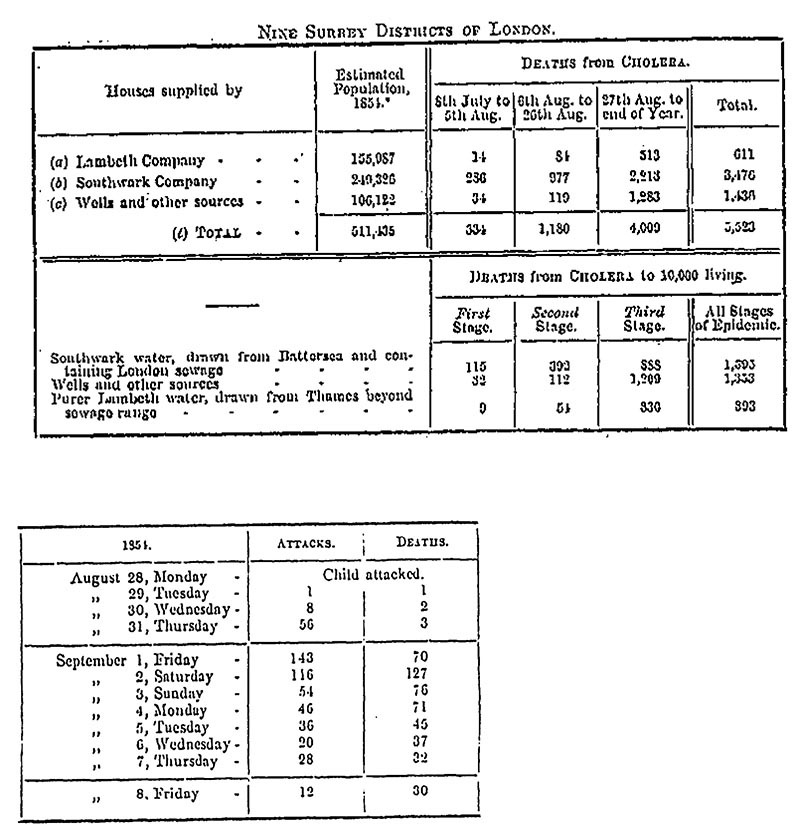

The chance to substantiate his conjectures with statistical proof arrived in 1854 with the Third Pandemic. During a serious outbreak in the region of Albion Terrace, he began a project that he termed his “Grand Experiment.”[14] Through an extensive survey of the neighborhood, he demonstrated that around six out of every seven cholera deaths had occurred in houses that received water from the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, instead of the Lambeth Company.[15] Though both companies drew their water from the Thames, the Southwark and Vauxhall Company drew further downstream, in a much more polluted area.[16] This strongly supported Snow’s postulated connection between cholera and contaminants in water. Although epidemiology textbooks still present Snow’s 1854 survey as a quintessential example of public health investigation,[17] it has been largely eclipsed in historical memory by his subsequent study during the outbreak on Broad Street.

In hindsight, it is widely believed that the events on Broad Street began with Frances Lewis, a five-month-old infant. As to how the child contracted the disease, we remain ignorant to this day. Dr. William Rogers attended her as she experienced diarrhea and exhaustion, both symptoms of cholera, without cramps or discolored skin. Frances died within a few days.[18] Her mother, Sarah Lewis, washed the soiled clothes and emptied the dirty water into a cesspool in front of the house. It did not take long for their Broad Street neighbors to contract the disease. Within ten days, the number of deaths from cholera exceeded five hundred. Snow himself would later describe it as “…the most terrible outbreak of cholera which ever occurred in this kingdom.”[19] In the years since, Britain has never again experienced an outbreak of the same magnitude.

John Snow lived in Soho. The area of Broad Street in question was but a few blocks from his house. He knocked on doors all around the Golden Square neighborhood, stopping at the houses of those who were healthy and well as those who were ill to inquire about the family’s consumption of water. He drew a map, which has subsequently become famous because of the precedent it set for modern epidemiological investigations, with a small black mark representing every death (see appendix I). At the center of the affected area was the Broad Street Pump.

At first the recorded data seemed to imply that the pump and the outbreak were unrelated. Some deaths had occurred much closer to other pumps, while some establishments on Broad Street within a block of the pump had escaped the scourge of cholera. With a little persistence, however, Snow found explanations that trans- formed these apparent inconsistencies into evidence supporting his theory.

Broad Street water had a reputation for being colder and more carbonated than the water from surrounding pumps, so it had attracted a clientele from adjacent neighborhoods. Upon interviewing the families of the deceased who had lived far away, Snow discovered that many of the children and adults had been in the habit of stopping to drink from the pump as they walked to school and work each morning. When he inquired how the employees of the Lion Brewery had all remained healthy despite working across the street from the Broad Street pump, their employer informed him that they seldom drank from the pump. They much preferred the liquor they received as part of their wages. The workhouse just down the road had inadvertently escaped the outbreak by using water from a private well. But perhaps the most convincing example was the death of Susannah Eley, a widow who had moved away from Broad Street to the distant district of Hampstead. Her surviving sons told Snow that she had retained a fondness for Broad Street water and regularly had it delivered to her new home. Thus, her death and the death of her visiting niece were readily explained. Snow concluded: “The result of the inquiry then was, that there had been no particular outbreak or increase of cholera, in this part of London, except among the persons who were in the habit of drinking the water from the above-mentioned pipe-well.”[20]

Armed with this data, Snow requested permission to address the Board of Guardians assembled by St. James’s Parish to deal with the continued problem of cholera. Although Snow’s ideas were controversial, the Board consented to his proposed plan of action—removing the handle of the Broad Street Pump. It was done the very next day. Upon digging at the sight of the pump, it was discovered that the well beneath it ran close to sewage pipes and cesspools in front of neighboring houses. We may never determine how the well was contaminated, but evidence suggests that it could have been the dirty water that Sarah Lewis discarded upon the death of her infected infant.

Snow’s work on cholera received mixed reviews during his lifetime. Though some of his colleagues were supportive, the president of the Board of Health, Benjamin Hall, and the former president, Edwin Chadwick, openly denounced his ideas. He was summarily rebuffed by the Committee for Scientific Inquiries, whose report read, “… we see no reason to adopt this belief. We do not find it established that the water was contaminated in the manner alleged …, nor is there before us any sufficient evidence.”[21] Furthermore, a competition in Paris offering £1,200 for a means of controlling the spread of cholera rejected his second, definitive version of On the Mode of the Communication of Cholera which he submitted in 1856.[22] In fact, the obituary printed in The Lancet following Snow’s death in 1858 briefly praises his research of anesthetics without even mentioning his work on cholera.[23] In Victorian England, his ideas were too novel and controversial to gain immediate acclaim.

However, the overwhelming statistical evidence gradually led the medical community to embrace his conclusions. Even the Committee for Scientific Inquires acknowledged in the appendix to its skeptical report, that “there are some cases of disease and death which we find ourselves unable to explain upon any other hypothesis than that of the deleterious influence of the water.”[24] Shortly after the publication of Snow’s findings, Reverend Henry Whitehead embarked on a similar investigative survey of the Broad Street area with the intention of disproving Snow’s theory. He was moved by his findings to agree with Snow and later called him “as great a benefactor in my opinion to the human race as has appeared in the present century.”[25] Snow’s beliefs became even more plausible in light of Louis Pasteur’s work on the germ theory of disease in 1859, and Robert Koch’s work with Vibrio cholerae under the microscope in 1884. In 1886, the Local Government Board credited Snow with, “demonstrating incontrovertibly the connection of cholera with the consumption of specially polluted water, startling the profession by the novelty of his doctrine, and inaugurating a new epoch of etiological investigation.”[26]

The Legacy

John Snow’s immediate contribution to history was the water-borne theory of cholera. This discovery gave society the ability to prevent the disease from spreading. When cholera returned to England in 1866, eight years after Snow’s death, the London physicians kept the disease under control “by the following of the light of his [Snow’s] researches.”[27] By common consent, cholera was the single worst epidemic disease of the nineteenth century.[28] It still poses a threat in underdeveloped areas of the world. The fact that we speak of it without fear in Europe and North America is remarkable in the context of the past few centuries. Finding a solution to cholera was as stunning as a solution to aiDS would be today.29 It is an achievement for which we must credit the work of many people, but principally John Snow.

The broader importance of Snow’s work is the emergence of epidemiology as a field of modern science. Without the techniques of microbiology, he analyzed the spread of disease by using simple statistics to demonstrate a correlation between two factors — water impurity and the occurrence of cholera. His logical methods shaped the way we confront public health dilemmas today. Maps such as his are employed so regularly that the practice now has an official name — medical cartography. Field studies in the style of the ones that he conducted in the cholera-stricken neighborhoods of London have a name as well — shoe leather epidemiology. His studies are frequently cited as models in lectures and textbooks.[30] Indeed, he is commonly referred to as “the father of epidemiol- ogy.”[31] Dr. David Satcher, the former director of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, reportedly approached the most challenging public health issues with the catch-phrase “Where is the handle on this Broad Street Pump?”[32] Among health-care professionals, Snow’s significance is now so apparent that in 2003, the readers of Hospital Doctor, a magazine circulated in the medical community, voted Snow as the Greatest Doctor in History — with Hippocrates himself finishing second.[33] Without question, Snow’s work forever changed our approach to health and medicine.

Notes

1. John Snow, “On the Mode of Communication of Cholera," 2nd ed., Snow on Cholera (New York: Hafner Publishing, 1965): 38.

2. G. C. Cook, “The Asiatic Cholera: An Historical Determinant of Human Genomic and Social Structure,” Cholera and the Ecology of Vibrio cholerae (London: Chapman and Hall, 1996): 20-21.

3. irwin Sherman, Twelve Diseases that Changed Our World (Washington DC: ASM Press, 2007): 33.

4. Ralph R. Frerichs, interview by author, digital recording of telephone conversation, 18 March 2009.

5. Peter Vinten-Johansen, email to author in response to questions, 25 March 2009.

6. “Epidemiological Society,” The Lancet 1 (1850): 156.

7. Rosalind Stanwell-Smith, interview by author, digital recording of telephone conversation, 5 April 2009.

8. Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society of London, Proceedings of the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society of London, Volume iii (1861):47.

9. John Snow, The Case Books of Doctor John Snow (London: Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, 1994): 271, 471.

10. Thomas Snow, “A Doctor’s Teetotal Address Delivered in 1893,” British Tem- perance Advocate, 1888: 182.

11. Benjamin Ward Richardson, “John Snow, M.D., A Representative of the Medical Science and Art of the Victorian Era,” The Asclepiad, 1887: 277.

12. Peter Vinten-Johansen et al, Cholera, Chloroform, and the Science of Medicine: a Life of John Snow. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003): 200-201.

13. John Snow, On the Mode of Communication of Cholera (London: Wilson and Ogilvy, 1849): 5-6.

14. Sandra Hempel, The Strange Case of the Broad Street Pump (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press): 165.

15. John Snow, “Cholera and the Water Supply,” The Times, 26 June 1856: 12.

16. Snow, Snow on Cholera, 90.

17. Leon Gordis, Epidemiology , 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company, 2000): 11; Manya Magnus, Essentials of Infectious Disease Epidemiology (Sudbury: Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 2008): 23-24.

18. Henry Whitehead, Report for the St. James Parish Cholera Inquiry Committee (London: J. Churchill, 1855): 163-165.

19. Snow, Snow on Cholera, 38.

20. ibid. 70.

21. General Board of Health, Report of the Committee of Scientific Inquiries in Relation to the Cholera Epidemic of 1854 (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1855): 52.

22. Richardson, “John Snow, M.D.,” 287.

23. “Births, Marriages, and Deaths,” The Lancet, 1858: 635.

24. General Board of Health, Appendix to Report of the Committee of Scientific Inquiries in Relation to the Cholera Epidemic of 1854 (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1855): 153.

25. Ralph R. Frerichs, “Snow on Cholera: A Sight and Sound Voyage into the History of Epidemiology,” John Snow – A Historical Giant in Epidemiology, 16 February 2009.

26. Local Government Board, Fifteenth Annual Report of the Local Government Board, Supplement Containing Reports and Papers on Cholera (London: Eyre and Spot- tiswoode, 1886): 110.

27. Thomas Snow, “Dr. Snow on the Communication of Cholera,” The Times, 20 November 1885: 4.

28. irwin Sherman, The Power of Plagues (Washington DC: ASM Press, 2006): 167.

29. Frerichs, interview.

30. Hempel, Strange Case, 165.

31. Frerichs, interview.

32. American Academy of Family Physicians, “FP Report, 17 May 2009.

33. Frerichs, “Snow on Cholera.

Annotated Bibliography

Primary Sources

“Births, Marriages, and Deaths.” The Lancet (1858): 635. The Lancet printed a brief obituary that praised Snow’s research on anesthetics without mentioning his cholera work. This underscores the idea that much of Snow’s acclaim came after his death.

“Epidemiological Society.” The Lancet (1850): 156-157. This brief article names John Snow as one of the founding members of the London Epidemiological Society.

General Board of Health. Report of the Committee of Scientific Inquiries in Relation to the Cholera Epidemic of 1854. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1855. Presented to the House of Commons in the year following the outbreak on Broad Street, this report is highly skeptical about John Snow’s theory, representing the skepticism of the broader medical community. I quote it in my paper.

General Board of Health. Appendix to Report of the Committee of Scientific Inquiries in Relation to the Cholera Epidemic of 1854. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1855. This was published as a supplement to the above report. Unlike the original report, it does not dismiss Snow’s theory completely. I quote it in my paper to demonstrate the gradual change in sentiment.

Local Government Board. Reports and Papers on Cholera in England in 1893. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1894. This document, regarding later outbreaks of cholera in England, was presented to the House of Commons many years after Snow’s death. By 1894, Snow’s ideas were entirely accepted, and the report is highly complimentary. This further demonstrated the medical community’s eventual embrace of Snow and his ideas.

Local Government Board. Fifteenth Annual Report of the Local Government Board, Supplement Containing Reports and Papers on Cholera. London: Eyre and Spot- tiswoode, 1886. Two decades after the Broad Street outbreak, Snow’s ideas had gained much greater favor. This report, presented to the House of Commons, praises Snow and his theory at great length. I quote it in my paper.

Registrar General. Report on the Cholera Epidemic of 1866 in England. London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1868. Like the preceding four documents, this report analyzing previous cholera outbreaks was presented to the House of Commons. It contains the reproductions of Snow’s data that I use in Appendix iii.

Richardson, Benjamin Ward. “John Snow, M.D., A Representative of the Medical Science and Art of the Victorian Era.” The Asclepiad, 1887, Vol. 4, pp 274-300. Benjamin Richardson was a colleague and intimate friend of John Snow. His relatively short biographical article published following Snow’s death provided unique insights into Snow’s thoughts, habits, and idiosyncrasies.

Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society of London. Proceedings of the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society of London, Volume iii (1861). Shortly after Snow’s death, the society praised Snow, particularly stressing the importance of his work with anesthetics. This is important because most people see his work on cholera as being his principal concern and his most successful endeavor. I quote this document in my paper.

Snow, John. “Cholera and the Water Supply” (Letter to the Editor). The Times 26 June 1856: 12, column B. Snow’s letter to the editor provides the statistic that roughly six cholera deaths occurred among individuals consuming Southwark and Vauxhall water for every one cholera death among consumers of Lambeth water. I use this statistic when describing the outbreak.

________. The Case Books of Doctor John Snow. London: Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, 1994. Although cholera research was the field that would earn Snow a place in history, the vast majority of his work with patients involved administering anesthetics. His case books demonstrate the importance he placed on this second pursuit and the diligence with which he worked.

________. “On the Mode of Communication of Cholera.” London: Wilson and Ogilvy, 1849. The John Snow Archive and Research Companion. Vinten-Johansen, Peter. Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI. 18 April 2009. This is the first edition of Snow’s most famous work. It is speculative and fairly short, published before both of his research experiments were conducted. His words demonstrate his awareness that the ideas he proposes are shockingly controversial. I quote this in my paper.

________. Snow on Cholera. New York: Hafner Publishing, 1965. This book is a reprint of two of Snow’s most famous papers on cholera, including the second edition of On the Mode of Communication of Cholera. I quote in several places from his explanation of his studies.

Snow, Thomas (edited). “A Doctor’s Teetotal Address Delivered in 1836.” British Temperance Advocate, November 1888: 182. Thomas Snow presents his brother’s arguments on behalf of temperance. This illustrates that Snow’s personal lifestyle, not just his views on cholera, differed markedly from the Victorian era medical community – most doctors did not endorse the temperance movement.

________. “Dr. Snow on the Communication of Cholera” (Letter to the Editor). The Times, 20 November 1885: 4, column F. Snow’s brother describes how physicians in London used Snow’s research to successfully manage a cholera outbreak in 1866. This is a concrete example of Snow’s impact on public health policy.

Whitehead, Henry. Report for the St. James Parish Cholera Inquiry Committee. London: J. Churchill, 1855. The John Snow Archive and Research Companion. Vinten-Johansen, Peter. Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI. 18 April 2009. Henry Whitehead presents a letter from the doctor who treated Sarah Lewis’s infant, substantiating the claim that the infant could have been the cause of the outbreak.

Personal Communications

Frerichs, Ralph R. Telephone Interview. 18 March 2009. Dr. Frerichs is a professor of epidemiology at UCLA. Like many in his profession, he has a high regard for John Snow as the father of epidemiology. He also has a detailed understanding of the history surrounding John Snow, as a result of constructing the website listed in the Secondary Sources section.

Stanwell-Smith, Rosalind. Telephone interview. 5 April 2009. Dr. Stanwell-Smith is a public health consultant and the Honorary Secretary of the John Snow Society in London. She spoke with me about Snow’s significance in the modern world, the efforts of the society to memorialize him, and the replica pump’s important role as a monument in Soho.

Vinten-Johansen, Peter. Email to the author. 25 March 2009. Mr. Vinten-Johansen is a retired history professor from Michigan State University. He is the author of Cholera, Chloroform, and the Science of Medicine: a Life of John Snow, which is widely regarded as the definitive Snow biography. He was able to answer some of my questions about minute details of Snow’s life and work that were not featured in the printed sources.

Secondary Sources

“Dr John Snow.” Durham University. 16 February 2009. This web article explains why one of the colleges within Durham University bears the name of John Snow. It also mentions the Hospital Doctor poll in which Snow was voted the greatest doctor in history.

“Drasar, Bohumil and Bruce Forrest. Cholera and the Ecology of Vibrio cholerae. London: Chapman and Hall, 1996. This book is a compilation of articles by various authors who discuss cholera from the scientific standpoint. It reveals an understanding of cholera that is completely different from the beliefs and speculations prevalent in the era of John Snow. Also, it describes the pathology and early history of cholera in greater detail than other sources.

“FP Report.” American Academy of Family Physicians. January 1997. aaFP News De- partment. 17 May 2009. This source reports that Dr. David Satcher and his colleagues try to approach modern public health dilemmas in the style of John Snow, just one example of Snow’s influence on modern epidemiology.

Gordis, Leon. Epidemiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company, 2000. Gordis’s textbook, designed for beginning epidemiology students, presents John Snow’s studies in London as a model of epidemiological investigation. This is concrete proof of Snow’s influence and significance in this field.

Hempel, Sandra. The Strange Case of the Broad Street Pump. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2007. Hempel takes the unique approach of beginning her narrative long before the events surrounding the pump, giving a detailed account of the British government’s futile attempts to restrain cholera during the second pandemic. Because this was one of the first books I found, the footnotes led me to several of my other secondary sources.

“John Snow: A Historical Giant in Epidemiology.” Frerichs, Ralph R. 1999. UCLA Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health. 16 February 2009. This is a very comprehensive website including both visual and audio accounts of Snow’s life and work. It lists numerous significant writings on John Snow, which helped my research considerably.

Johnson, Steven. The Ghost Map. New York: Riverhead Books, 2006. This book provided the image of Snow’s portrait presented in Appendix ii.

Magnus, Manya. Essentials of Infectious Disease Epidemiology. Sudbury: Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 2008. This textbook contains a thorough description of John Snow’s mapping techniques and statistical data, presenting them to epidemiology students as quintessential examples of important skills.

Morris, Robert. The Blue Death: Disease, Disaster, and the Water We Drink. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2007. Morris devotes the first few chapters to John Snow and the other major players in the 19th century cholera frenzy, but then he moves on to discuss the work of later scientists in perfecting our understanding cholera. Ultimately, this organizational format shows the modern-day applications of what we have learned about water-borne illnesses.

Sherman, Irwin. The Power of Plagues. Washington DC: ASM Press, 2006. This book generalizes the impact of infectious diseases on society, devoting one chapter exclusively to cholera.

________. Twelve Diseases that Changed Our World. Washington DC: ASM Press, 2007. Sherman’s second book is very similar to his first, with slightly more emphasis on human, rather than natural, history.

Vinten-Johansen, Peter, Howard Brody, Nigel Paneth, Stephen Rachman, and Michael Rip. Cholera, Chloroform, and the Science of Medicine: a Life of John Snow. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. The John Snow Society recommends this as the single best account of John Snow’s life and works. It provided more detail than other books and articles did, and its footnotes are more extensive.

APPENDIX I

Snow’s famous map of the Broad Street area. Each black mark represents one death from Snow’s famous map of the Broad Street area. Each black mark represents one death from cholera. From Snow on Cholera by John Snow.

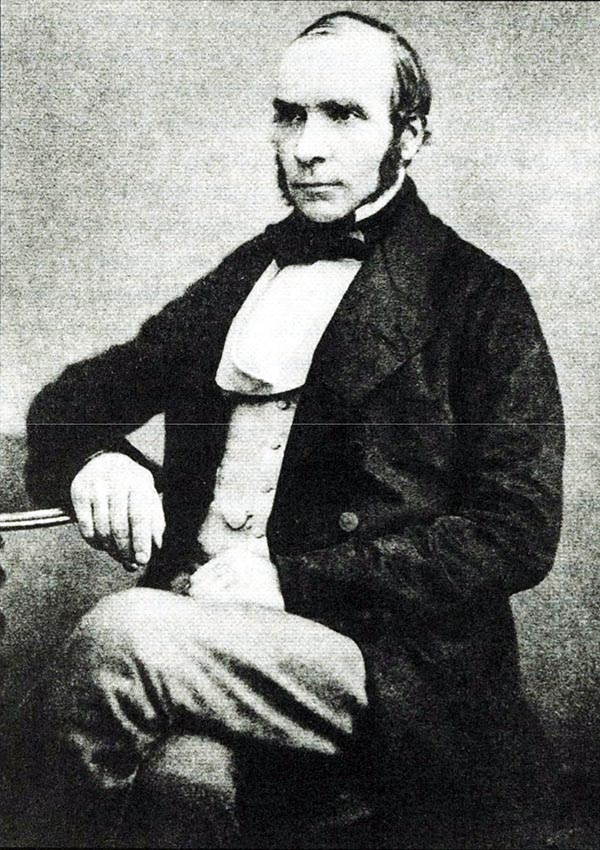

APPENDIX II

Portrait of John Snow. From The Ghost Map by Steven Johnson.

APPENDIX III

Tables presenting the statistics from Snow’s cholera investigations regarding the Lambeth Company versus the Southwark and Vauxhall Company (top) and the outbreak in the Golden Square neighborhood near the Broad Street pump (bottom). From Report on the Tables presenting the statistics from Snow’s cholera investigations regarding the Lambeth Cholera Epidemic of 1866 in England by the Registrar General.

APPENDIX IV