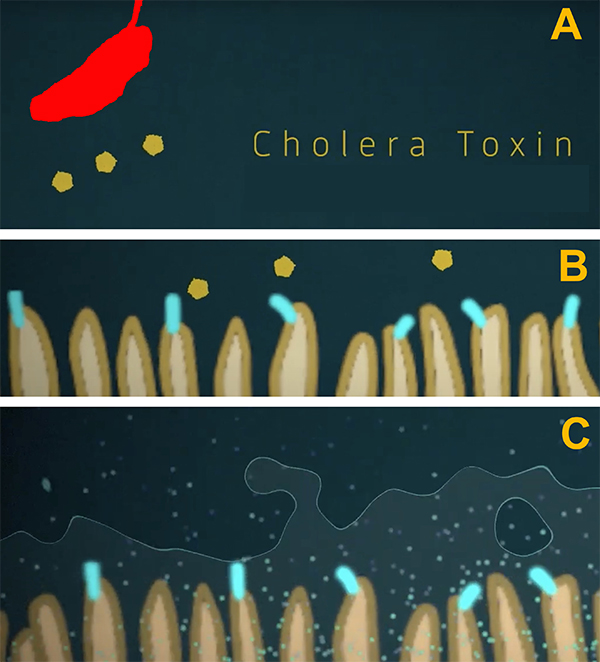

During the mid-1800s, there were two major theories on the cause of cholera being debated widely in medical circles throughout London. The bacterium organism seen here that caused cholera, Vibrio cholerae, was not yet widely known and would not be until 1883, twenty five years after the death of John Snow. In that year, Robert Koch, a German physician and bacteriologist, discovered the etiologic microbe with its polar flagellum that acts as a tail-like propeller in water, apparently unaware of microscopist Felippo Pacini's earlier description of cholera in 1854. Yet prominent scientist Koch, a year later in 1884 was the first to both isolate and culture Vibrio cholerae in pure culture, allowing for replication by others.

Aside - Cholera Toxin

Aside - Cholera Toxin

While Koch had suggested the existence of a cholera toxin in 1884, it was not until 1959 that the cholera toxin was discovered by Indian medical scientist and researcher Sambhu Nath De, Ph.D. (1915–1985) at Calcutta Medical College. Sambhu Nath De isolated the toxin and experimentally demonstrated its role in causing cholera. He was nominated several times for the Nobel prize but did not receive it. Yet he did receive high praise and many other acknowledgements.

Source: https://science.thewire.in/society/history/sambhu-nath-de-story-video/

As Dr. Sambhu Nath De discovered, only some forms of the bacteria Vibrio cholerae (i.e., the toxigenic varieties) liberate a toxin. It is this toxin that causes the deadly cholera disease.

Starting in panel A, when contaminated water is swallowed, toxigenic strains of Vibrio cholerae (in red) liberate a toxin (in gold). In panel B, the toxin flows to the cells that line the intestinal wall, which sets off a reaction in the cells. In panel C, the damaged cells allow fluid loss from the body, resulting in dehydration and often death, unless the body is quickly rehydrated.

John Snow and his medical colleagues in the mid-1800s knew nothing of a toxigenic strain. Some like Snow reasoned that an unidentified microbe (i.e., the germ theory) caused gastrointestinal damage, resulting in vomiting, diarrhea and eventual death. Others, including many physicians at the time, believed in the "miasma theory," further described below.

Sambhu Nath De, M.B ., D.T.M., (Calcuta Medical College) and Ph.D. (UCL Medical School, London).

Calcuta Medical College, India

End of Aside - Cholera Toxin

End of Aside - Cholera Toxin

MAIN TWO THEORIES OF CHOLERA

MIASMA THEORY

Many in the early to mid-nineteenth century felt that cholera was caused by bad air, arising from decayed organic matter or miasmata. "Miasma" was believed to pass from cases to susceptibles in diseases considered contagious. Believers in the miasma theory stressed eradication of disease through the preventive approach of cleansing and scouring, rather than through the purer scientific approach of an emgering discipline like microbiology.

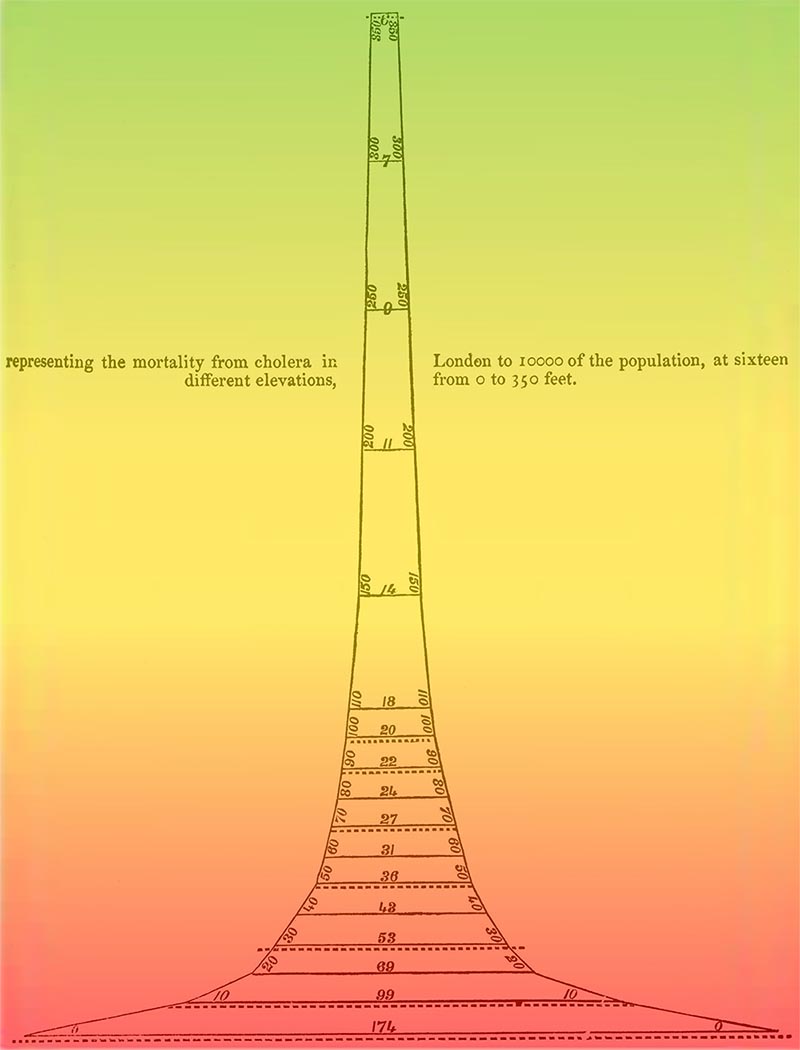

A prominent supporter of the miasma theory was Dr. William Farr, then assistant commissioner for the 1851 census and a career employee of the government's General Register Office, tallying births, deaths, marriages and the like. For a while, Farr was convinced that cholera was transmitted by air. He reasoned that "soil at low elevations, especially near the banks of the River Thames, contained much organic matter which produces miasmata. The concentration of such deadly miasmata clouds would be greater at lower elevations than in communities in the surrounding hills. His calculations in 1852 seemed to support this theory as shown in his graph below of cholera mortality by elevation [color added by Frerichs].

Those with the lowest elevations (also closer to the River Thame) shown in the red zone have the highest mortality, while those at the top high elevation level in the green zone have the lowest mortality.

Farr's findings of higher cholera mortality closer to the River Thames might well have been confounded by those living closer to the River Thames being more likely to consume contaminated river water. John Snow did not agree with the miasma theory of bad air. Instead he believed that cholera was transmitted via contaminated water by a microbe of some form or another.

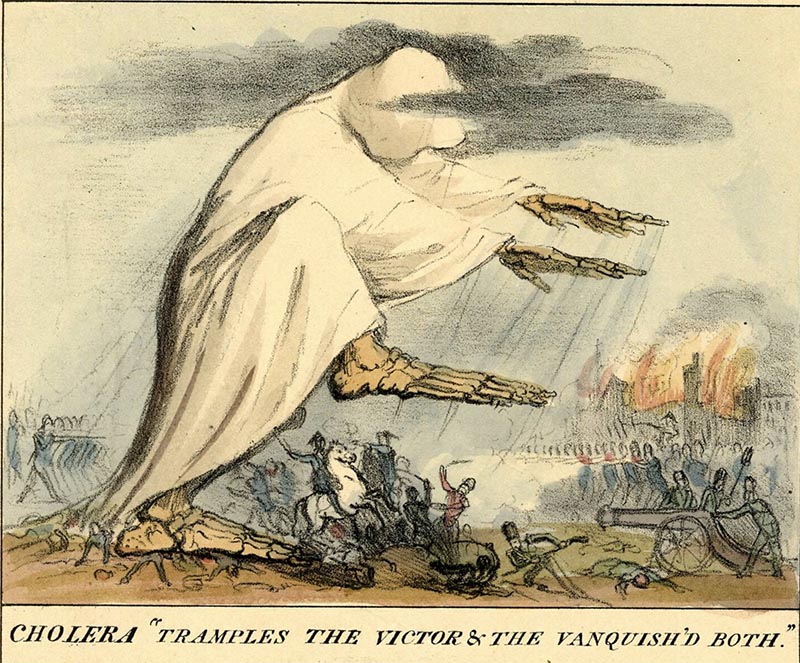

Yet most people in the 1830s and 40s, including nurses and doctors, believed in the miasma theory, as illustrated by popular caricaturist Robert Seymour (1798–1836).

In 1828, 30-year-old British illustrator Robert Seymour was living in Lisbon, Portugal. He reflected on how cholera had spread in past years from its origin in the Ganges Delta in India along trade routes established by Europeans. The deadly disease then came and went during numerous conflicts that plagued eastern European territory at the time. Responding with an illustration, he drew "Tramples the Victor and the Vanquish'd Both" (see below), reflecting on the indiscriminate nature of deadly diseases in wartime.

Later in 1832 when cholera reached London and the miasma theory was active in the public's mind, publisher Thomas McLean added Seymour's illustraton to his monthly sheet of caricatures (No. 22). This time, the shrouded skeletal figure of cholera was reenvisioned as a miasmic cloud, vanquishing all persons that it encountered in a raging battle field.

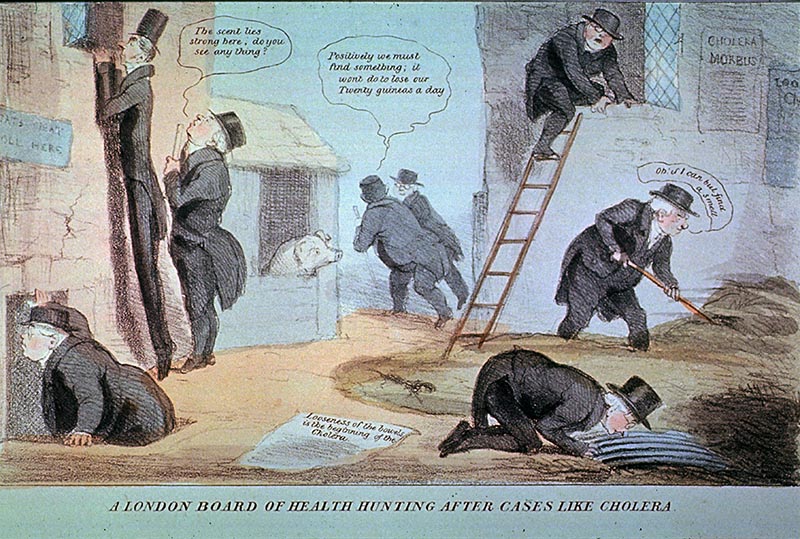

By 1832, epidemic cholera had emerge a year before for the first time in England, causing the death of over 5,000 people in London alone. Sensing the public's emotions, Robert Seymour created a second caricature of cholera, this time involving local medical personel, entitled "A London Board of Health Hunting After Cases Like Cholera," again invoking the miasma theory. As seen below there is a paper on the ground with headline: "Looseness of the bowels is the beginning of cholera." In the upper left, one person says to another, "The sent is strong here: do you see anything?" Two others in the center are spurred on by financial concerns: "Positively we must find something; it won't do to lose our twenty guineas a day." At the right is a man digging with a shovel, thinking "Oh, if I could find a smell."

GERM THEORY

The alternative theory, supported by John Snow, held that cholera was caused by a microbial cell, not yet identified. He reasoned that this microbe was transmitted from one person to another by drinking water. Snow's germ theory was deemed "peculiar" by John Simon, head medical officer of London, but has since met the test of time. What was this peculiar theory?

Here is a summary written by Dr. Simon:

"This doctrine is, that cholera propagates itself by a 'morbid matter' which, passing from one patient in his evacuations, is accidentally swallowed by other persons as a pollution of food or water; that an increase of the swallowed germ of the disease takes place in the interior of the stomach and bowels, giving rise to the essential actions of cholera, as at first a local derangement; and that the 'morbid matter' of cholera having the property of reproducing its own kind must necessarily have some sort of structure, most likely that of a cell."

While Dr. Simon clearly understood John Snow's theory, he joined others in questioning the relevance of the germ theory to cholera.

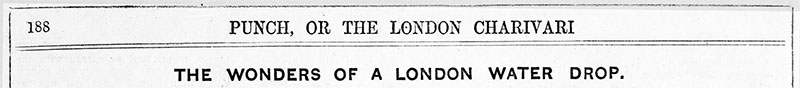

Between August 1849 when Snow published his pamphlet titled "On the Mode of Communication of Cholera" and 1852 prior to his seminal studies on the Broad Street Pump Outbreak and the "Grand Experiment," there was almost no public support for Snow's "germ theory." Only one publication, Punch, had a positive llustration, and even that was not signed by an illustrator. Rumor has it that the llustration shown below was drawn by caricaturists Richard Doyle (1824-1883) or John Lynch (1817-1864), both working for Punch at the time and both very prominent.

Source: "The Wonders of a London Water Drop". Punch Vol. 461, May 11, 1850, p. 188.

Following the release of John Snow's epidemiological studies in 1854-55, cartoonist John Lynch stepped up in Punch with the graphic implication that River Thames water caused cholera. Yet he also mixed in diphtheria (a bacterial infection caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae, primarily spread from person to person via respiratory droplets) and "scrofula" (a form of tuberculosis affecting lymph nodes, most commonly in the neck). Alas, the supportive cartoon appear on July 3, 1858, about two weeks after the death of John Snow.

Source: Punch page 5, July 3, 1858.

WILLIAM FARR

For some while, William Farr was the leader of the "pro-miasma" health scientists. Yet later, he changed his mind as Snow's data were published, and other supporting facts appeared. So who was William Farr? As it turns out, his origin was very similar to John Snow's, coming from a lower socio-economic class background.

William Farr (1807-83), like John Snow, was the child of a farm laborer. He was born on November 30, 1807 at Kenley in Shropshire. Fortunately, at an early age he was adopted or at least financially supported by Joseph Pryce of Shrewsbury, the squire of his parents' community. His early years were spent studying at public day schools, supplemented with tutoring by a local minister.

Age 19. In May 1826, he joined the staff of a local infirmary in Shrewsbury, commuting from home six days a week for the next two years. His preceptor was Dr. Webster.

Age 21. His early benefactor, Joseph Pryce, died in November 1828 and left William Farr a small inheritance. The money was enough to take Farr to Paris, France a few months later to study medicine. Farr remained in Paris from April 1829 to July 1830,when the July Days insurrection overtook France.

Age 23-25. On returning to England, Farr attended medical lectures at University College, London from 1830-32. In March 1832, he passed the examination of the Society of Apothecaries which allowed him to practice medicine. Early the next year, he married and both lived and had his medical practice at 8 Grafton Street in Fitzroy Square

Age 28. Rather than continuing with his private practice, Farr turned increasingly to medical journalism. At first he wrote articles that appeared in The Lancet. Beginning in 1835, he served as a medical editor of the British Medical Almanack and then started editing his own journal.

Age 30. Farr's wife died of tuberculosis in 1837, which stimulated a life-long interest in this disease. In the same year, his medical preceptor, Dr. Watson, also died and left him both money and his library.

Age 31. In 1838, Farr obtained the post of compiler of abstracts (i.e., birth and death certificates) in the registrar general's office. He remained with this government agency for forty years, rising eventually to superintendent of the Statistical Department.

Age 35. Farr married his second wife in 1842 and had eight children in the following years.

Over time he became well known for his use of vital statistics, and published much of his work in Reports of the Registrar-General, 1839-80, the same publication used by John Snow to test the germ theory of cholera.

Age 47. In 1854, Farr was appointed member of the Scientific Committee for Scientific Enquiries in Relation to the Cholera Epidemic of 1854. Given his support of the miasma theory, this platform lead to conflicts with John Snow. A report was issued in 1855.

Farr's Committee wrote: "In explanation of the remarkable intensity of this outbreak [Broad Street Pump outbreak] within very definite limits, it has been suggested by Dr. Snow, that the real cause of whatever was peculiar in the case lay in the use of one particular well, situated at Broad Street in the middle of the district, and having (it was imagined) its waters contaminated with the rice-water evacuations of cholera patients. After careful inquiry, we see no reason to adopt this belief. We do not feel it established that the water was contaminated in the manner alleged; nor is there before us any sufficient evidence to show whether inhabitants of that district, drinking from that well, suffered in proportion more than other inhabitants of the district who drank from other sources."

The Committee added support to the miasma theory when elsewhere in the 1855 report they concluded:

"But, on the whole of evidence, it seems impossible to doubt that the influences, which determine in mass the geographical distribution of cholera in London, belong less to the water than to the air."

Age 59. By 1866, eight years after the death of John Snow, medical opinion had changed to support the germ theory of cholera and its waterborne transmission. Farr wrote a detailed report in 1866 that relied heavily on his extensive knowledge of statistics. Using death rates to justify his conclusions, he publicly acknowledged that water was the most important means of transmission, not miasmata as previously stated.

Age 75. Shortly after his retirement, William Farr died due to bronchitis on April 14, 1883, the same year Robert Koch discovered Vibrio cholerae. Three years earlier in 1880, he had received the Gold Metal of the British Medical Association, acknowledging his considerable contributions to the field of biostatistics. Farr had outlived John Snow by 25 years, but long since recognized the error of the miasma theory as the cause of cholera transmission.

Debate and Legislative Action

The debate between supporters of the miasma and germ theories extended well beyond cholera and had major legislative impact. The debate also invoked a strong editorial in The Lancet, highly critical of John Snow for his germ theory views, presented in the next section.

SNOW'S TESTIMONY

Much effort was underway in nineteenth century London to improve the health of the public. Besides contaminated water, the air was polluted with heavy fumes from various industries. The prevailing miasma theory focused attention on the sanitary state of the environment, presenting a sound instinct but incomplete biological understanding of the link between exposure factors and disease.

To address some of these disease-transmission problems, a law was passed by Parliament in 1846 (Nuisances Removal and Diseases Prevention Act). It was commonly known as the Cholera Bill, and likely was favored by Dr. John Snow. The bill was used during the cholera epidemic of 1848-9 to encourage property owners to clean their dwellings and connect them to sewers.

Proposed Admendment

Several years later in 1855, an amendment to the Act was proposed to regulate industries such as gas works, bone-boiling works and similar establishments which released fumes into the atmosphere. Supporters of the miasma theory favored this amendment, feeling that causative agents of disease are transmitted by air, killing with effluvia, and thus should be addressed by the manufacturers.

Being a strong supporter of the germ theory (perhaps too strong, extending his thoughts to diseases other than cholera which may not have a respiratory origin), Dr. Snow was asked by various manufacturers to testify on the proposed amendment. This he did as the second witness on March 5, 1855 to a Parliamentary committee chaired by Sir Benjamin Hall (1802-67).

Hall was a legislator who in 1855 became Chief Commissioner of Works and was responsible for improvements to the royal parks and for the final stage of the rebuilding of the Houses of Parliament. He was a tall, imposing man (at left) and was the source of the name "big Ben" for the new clock in the Parliament. Although not a physician, Hall became a strong proponent of environmental sanitation and public health, perhaps due to his belief in the miasma theory and the need for cleanliness of vapors.

The Monday, March 5, 1855 Testimony

John Snow was called to testify regarding his beliefs. The questions on March 5, 1855 are shown below in italics and Snow's response in regular black text. The Committee started its questions at 117 and ended at 172. Testimony was limited to Snow's notions and opinions, but was not allowed to be supported with his experimentation or other research studies, or illustrated with tables or graphs.

117. [Chairman, Sir Benjamin Hall] "Do you practice as a medical man in the Metropolis?"

"Yes in Sackville Street."

118."You wish to give some evidence upon the Nuisances Removal and Diseases Prevention Act?"

"I have been requested to give evidence on behalf of the trades people in the south districts of London, more particularly."

119."Upon what point?"

"I received a request from Mr. Knight. I was asked if I would give evidence on behalf of the manufacturers whose interests are threatened by the Nuisances Removal Act. I have not seen the parties, nor learnt any particulars. From my printed publication they have learnt that my opinion is, that measures necessary to protect the public health would not interfere with useful trades; and I believe it is on that account that they have asked me to give evidence on their behalf, and I have expressed my willingness to do so."

120."To what points would you desire to draw the attention of the Committee as regards the sanitary question?"

"I have paid a great deal of attention to epidemic diseases, more particularly to cholera, and in fact to the public health in general; and I have arrived at the conclusion with regard to what are called offensive trades, that many of them really do not assist in the propagation of epidemic diseases, and that in fact they are not injurious to the public health. I consider that if they were injurious to the public health they would be extremely so to the workmen engaged in those trades, and as far as I have been able to learn, that is not the case; and from the law of the diffusion of gases, it follows, that if they are not injurious to those actually upon the spot, where the trades are carried on, it is impossible they should be to persons further removed from the spot."

121."Are the Committee to understand, taking the case of bone-boilers, that no matter how offensive to the sense of smell the effluvia that comes from bone-boiling establishments may be, yet you consider that it is not prejudicial in any way to the health of the inhabitants of the district?"

"That is my opinion."

122. [Mr Greene] "Does that extend to all animal substances?"

"No. I believe that epidemic diseases are propagated by special animal poisons coming from diseased persons, and causing the same diseases to others, and that they are extremely injurious; but that substances belonging to animals, that is to say, ordinary decomposing animal matter, will not produce disease in the human subject."

123."Do you apply that, also, to decaying vegetable matter; do you consider that that will not be productive of disease?"

"I do not believe that decaying vegetable matter would be productive of disease; at least, it is a matter open for discussion whether certain decomposing vegetable substances, in marshy districts, may not produce agues; but in London, in any trade I am acquainted with, I do not believe that any decomposing vegetable or animal matters produce disease."

124. [Chairman, Sir Benjamin Hall] "Take the case of a bone-boiling establishment, or a "knackers" yard [a place where old or injured animals, especially horses, were slaughtered and their bodies processed]; assuming that there is a large number of horses in a state of decomposition, from which of course there would be very offensive effluvia, as far as the sense of smell is concerned, do you apprehend that that would not be prejudicial to the health of the inhabitants round?"

"I believe not."

125. [Mr Adderley]"Have you never known the blood poisoned by inhaling putrid matter?"

"No; but by dissection wounds the blood may be poisoned."

126."Never by inhaling putrid matter?"

"No; gases produced by decomposition, when very concentrated, will produce sudden death; but where the person is not killed, if the person recovers, he has no fever or illness."

127. [Mr Egerton] "You mean to say, that the fact of breathing alr which is tainted by decomposing matter, either animal or vegetable, will not be highly prejudicial to health?"

"I am not aware that it is, unless it be in such quantities as to produce actually fatal effects at the moment; but to produce those effects it requires that it should be highly concentrated."

128."Do you not know that the effect of breathing such tainted air often is to produce violent sickness at the time?"

"Yes, when the gases are in a very large quantity, as in a cesspool."

129."Do you mean to tell the Committee that when the effect is to produce violent sickness there is no injury produced to the constitution or health of the individual"

"No fever or special disease."

130. [Mr Greene] "Are you not aware that persons going into vaults where there are a number of dead bodies have suffered very severely, and that sometimes death has been produced by this cause?"

"Yes, when those gases are extremely concentrated, they will actually poison a person and cause death, but not cause disease; those poisons do not reproduce themselves in the constitution."

131."Are you not aware that, in cases of this kind, illness has sometimes been produced from which persons have suffered for a considerable length of time before death ensued"

"I am not satisfied upon that point. If illness has followed I think it has been a coincident."

132."Are you not aware that, in cases of this kind, illness has sometimes been produced from which persons have suffered very severely, and that sometimes death has been produced by this cause"

"Yes, when those gases are extremely concentrated, they will actually poison a person and cause death, but not cause disease; those poisons do not reproduce themselves in the constitution."

133. [Mr Egerton] "You say that the effluvia arising from living subjects are dangerous?"

"Or even from certain persons who have died from disease"

[These points were then repeated by Snow in response to four similar questions by Mr. Wilkinson.]

138. [Chairman, Sir Benjamin Hall] "I understand you to say that such effluvia, when highly concentrated, may produce vomiting, but that they are not injurious to health. How do you reconcile those two propositions?"

"If the vomiting were repeatedly produced, it would certainly be injurious to health. If a person was constantly exposed to decomposing matter, so concentrated as to disturb the digestive organs, it must be admitted that that would be injurious to health; but I am not aware that, in following any useful trade or manufacture, the effects ever experienced."

139."You consider that occasional sickness would be of no consequence, but that only frequent occurrence of the attacks would be injurious?"

"I am not aware that any occasional sickness is produced in any useful trade or manufacture."

140. [Mr Egerton]" Do you not know that the effect of a very strong offensive smell often is to produce vomiting?"

"The gases must be very concentrated to do that, except it be by a kind of sympathy. Persons are often much influenced by the imagination."

141."Where does your practice lie?"

"I am living in Sackville Street, Piccadilly."

142. [Mr Wilkinson] "I believe you are frequently in the habit of administering chloroform?"

"Yes."

143."And therefore your attention has been particularly called to the effect of the administration of gases?"

"Yes."

144."Have you turned your attention to the effects of the late outbreak of cholera in London?"

"Yes, I made special enquiries throughout Lambeth and Southwark and Newington."

145."Have you satisfied yourself by those inquiries of any particular results of that outbreak of cholera, so as to state your opinion of what has been the mode of propagation of the disease?"

"I have satisfied myself completely, that the chief mode of propagation of cholera in the South district of London, throughout the late outbreak, was by the water of the Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company containing the sewage of London; and containing consequently whatever might come from the cholera patients in the crowded habitations of the poor; and I am satisfied that it spread directly from individual to individual, sometimes in the same family, but by similar means; that is, by their swallowing accidentally what came from a previous sick patient."

146."Do you believe that there is evidence to show that cholera has been propagated almost entirely by the poison being taken in at the mouth?"

"Yes."

147."Absolutely swallowed?"

"Yes, it is my belief in every case."

148. [Mr Egerton] "Has your practice lain much amongst the poor?"

"Not so much latterly as it did at one time; but it did very much till seven years ago."

149."In what district?"

"In a district near Soho Square, running as far as Seven Dials."

150."You have stated that in the course of your inquiry you satisfied yourself that water was the principal cause of communicating cholera, after the water had been impregnated by the existence of the cholera. Did you satisfy yourself what was the original cause of cholera in those persons who were not so affected by the water?"

"I consider that the last outbreak of cholera was introduced from the Baltic Fleet into the Thames. I consider that the cause of cholera is always cholera; that each case always depends upon a previous one."

151."You have stated that, in your opinion, these offensive trades have no injurious effect upon the health; will you state by what means you have arrived at that conclusion; whether it is by lengthened experience derived from medical attendance upon those who carry on these trades or whether it is a theory?"

"It is derived in various ways, but chiefly rather in a negative way; from my having satisfied myself on other causes of disease quite independent of those trades; also from my general medical opinions, and also from my experience amongst trades people who have been exposed to those things."

152."As your medical practice has not been amongst men who follow those occupations, by what means do you arrive at the fact that their health is not affected by them?"

"I have attended people in every occupation, and my opinion is derived also from reading, and from personal information."

153."Is your opinion derived from practical experience, or is it mere theory of your own?"

"My theory is derived from practice, and from observation."

154."Will you state in what particular localities of London you practiced as a medical man, so as to be able to express that opinion so confidently to the Committee?"

"My practice amongst the poor extended chiefly between the Thames and Oxford Street; I have not turned my special attention to any particular trades; I never was called upon, till two or three days ago to consider this subject particularly."

155."The point at which we particularly wish to arrive here is the effect of particular trades upon the health of individuals. You say that you believe that these offensive trades have no effect upon the health of individuals; by what means do you arrive at that conclusion?"

"Partly by my own observation, partly by reading."

156."Will you state where your observation was obtained; because, in the locality that you mention, between the Thames and Oxford Street, there are few, if any, soap-boilers or bone-crushers, or any of those trades?"

"There are people who collect the bones in the rag shops; but in the hospitals I have seen patients from every part of London."

157."Has your attention ever been directed, as a medical man, to those particular parts of London about Bermondsey, and other districts, on the south side of the water: Have you ever practiced as a medical man there?"

"I have not practiced there; I have visited patients there: but for several weeks in the last autumn I went to the houses of 700 people who had died of cholera, and I knew their actual occupations, and their age, as it was entered in the Registrar General's reports, and I examined the tables at the time."

158."In what part of London did you make those inquiries?"

"Throughout the whole of Lambeth, St. Georges, Southwark, and the whole of Newington, and St.Georges Camberwell; I inquired respecting every case of cholera in the first seven weeks of the epidemic."

159."But you do not practice as a medical man in these particular districts?"

"No, I live in Sackville Street; I have lived there for three years; previously to that I lived in Frith Street, Soho Square. I did not attend those patients on the south side of London, but I went afterwards to the houses making inquiries, to find out the nature of their supply of water; and in doing that I learnt a number of other particulars about them. I always knew the occupation of the deceased person."

160.[Mr. Egerton] "Do you dispute the fact that putrid fever and typhus fever hang about places where there are open sewers?"

"Sometimes"

161."How do you account for that?"

"It is a coincidence. Where there are open sewers you have mostly a number of people living together under such circumstances that they get fever, which is communicated from one person to another; very often the water of the pump wells is impregnated with the excrements of the people, which soaks into the wells. And the general water supply in certain districts is also very bad."

162. [Mr. Wilkinson] "Did not you make particular inquiries at the houses which were supplied by two companies which take their supply of water from different places?"

"Yes; the one is supplied from Battersea Fields, near Vauxhall Bridge, and the other from Thames Ditton."

163."Was there a very marked difference between them?"

"There was. In the first four weeks of the epidemic the mortality was fourteen times as great amongst the customers of the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, getting their water in Battersea Fields as in the other, taking into account the number of houses supplied by each company."

164."You have made very extensive statistical inquiry as to the diseases which you have mentioned?"

"I have."

165."Have you in any case traced the propagation of those diseases, or of the cholera, to the existence of offensive trades?"

"I have every reason to believe that those trades have not had any influence whatever."

166."In any single instance that you have visited in those places, were you ever able to trace any case of the propagation of disease by any of the offensive trades?"

"No; on the contrary, I am satisfied that such influences have no effect whatever. Last autumn there was not much cholera about Fore Street, Lambeth, and all that district. That district suffered extremely in 1849; but in 1854 it suffered very slightly. All the other facts remain the same; but that district is now chiefly supplied by the Lambeth Company with improved water."

[Questions were then posed concerning the cause of diseases among persons at the Milbank Prison. Of note was question 172.]

172. [Mr. Langton] "Is it not possible that the same poisonous qualities which affect the water may be floating in the air?"

"That is possible; but I believe that the poison of the cholera is either swallowed in water, or got directly from some other person in the family, or in the room; I believe it is quite an exception for it to be conveyed in the air; though if the matter gets dry it may be wafted a short distance."

Sources:

Lillienfeld, D. American J Epidemiology 152(1), 4-9, 2000.

Lucken, B. Pollution and Control -- A Social History of the Thames in the Nineteenth Century, 1986.

Halliday, S. The Great Stink of London, 1999.

Roebuck, J. Urban Development in 19th Century London -- Lambeth, Battersea Wandsworth 1838-1888, 1979.

Wohl AS. Endangered Lives -- Public Health in Victorian Britain, 1983.

The Impant of the March 5, 1855 Testimony

Following John Snow's testimony, the Committee continued to deliberate until May 1855, followed by their final report published in June 1855. After reading the report, The Lancet reacted quickly and critically to Snow's testimony and on June 23, 1855 published an editorial that condemned Snow's views, voicing the opinion that "the well whence Dr. Snow draws all sanitary truth is the main sewer." More in the coming sections.

On the legislative front, the The Nuisances Removal and Diseases Prevention Act bill had its third hearing in July 1855, and thereafter made considerable revisions, including favorable changes for the "offensive trades," notably gasworks and bone-boiling works. On August 14, 1855, the bill became law.

In 1856, the General Board of Health published its report confirming the role of water-borne cholera transmission, aligning with John Snow.

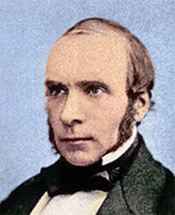

Thomas Wakley

Thomas Wakely (1795-1862) was well known as a London surgeon, journalist and politician, with a bent towards social reform. He started the medical journal The Lancet in 1823, named after a surgical tool to "cut out the corruption in medicine." He served as editor from its inception until his death in 1862, a span of 39 years, fostering London's leading and most influential medical journal.

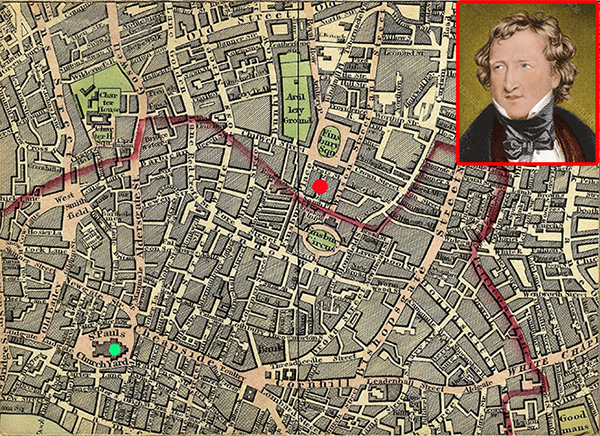

In 1835, he became a Member of Parliament (MP - House of Commons) with a social reform orientation, representing the newly formed Finsbury borough (red dot, northeast of St. Paul's Cathedral - green dot), remaining until 1852. This added considerable political power to his journalistic position.

Wakley was considered pugnacious, apparent early on in his schooling years when he was a bare-knuckle boxer in public settings, earning funds to further his medical education.

Source: Mogg's Strangers Guide To London, 1834

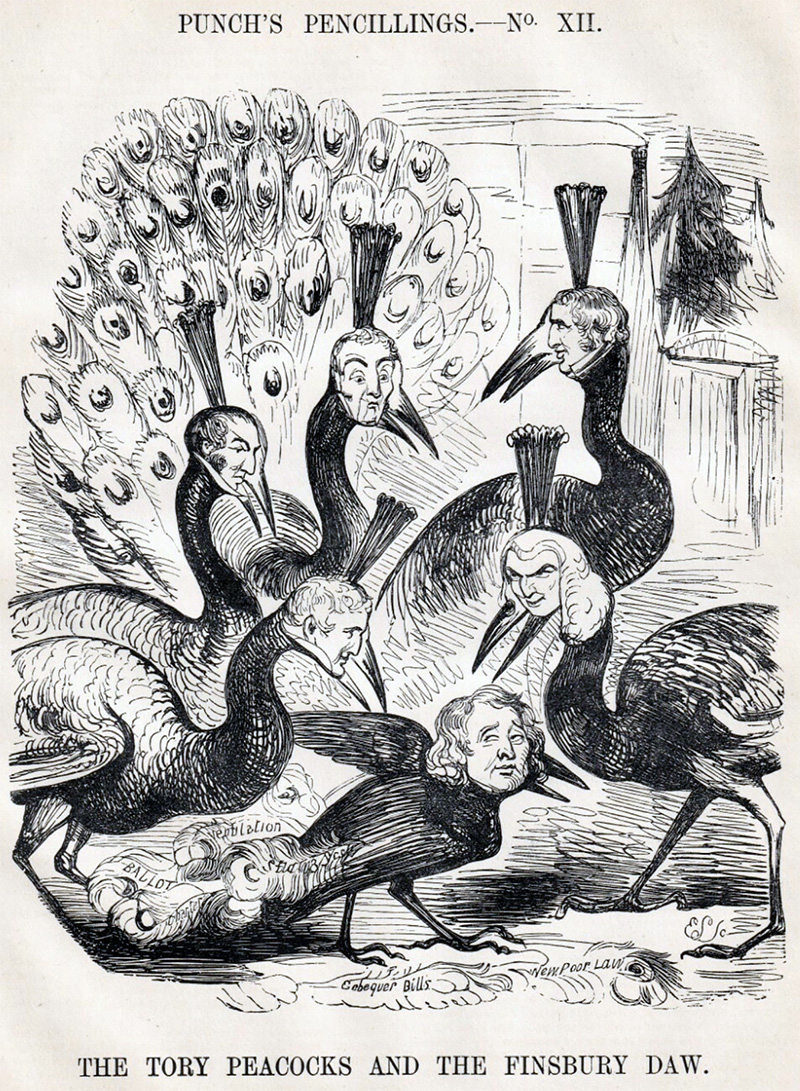

In 1841, Punch printed a political cartoon [no artist was listed, but probably John Leech (1817-1864)] of the House of Commons' Wakley and his Tory colleagues in the House of Lords. He is seen as the "Finsbury Daw" (i.e., a black crow from the Finsbury borough) plucking the eloquent peacock feathers of the Tories. The cartoon effectively addressed both Wakley's combative style and his political influence.

Source: Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol 1, 1841.

The Lancet Reaction and Committee Action

As mentioned above, following Snow's testimony, the Committee for the amended Nuisances Removal Act deliberated into May 1855 and issued a report in June 1855, reacted to by The Lancet.

The Lancet in earlier years had been supportive of the germ theory, but with the partial retirement of Thomas Wakley and the emergence as future editors of his sons James and Thomas, seemed increadingly to side with the environmental sanitation policies of the miasmatic theorists. The journal was highly critical of Dr. Snow, but did not clarify the scientific basis for its vitriolic dissent, nor the identity of the editorial writer, believed to be Thomas Wakley (see below). In contrast, The Lancet was very supportive of Dr. William Farr who at that time did not favor the germ theory, but instead used,existing mortality data in support of the miasma theory.

TWO LANCET EDITORIALS IN JUNE 1855

Two lengthy editorials appeared in the June 23 and June 30, 1855 issues of The Lancet, responding to Dr. Snow's testimony. Excerpts are presented below in italics, with comments in regular black text.

The Lancet, June 23, 1855

THE PUBLIC HEALTH AND NUISANCES

REMOVAL BILL: DR. SNOW'S EVIDENCE

It is the misfortune of Medicine, in its conflict with the prejudices of society, that it is continually exposed to discomfiture, through the perverse, crotchety, or treasonable behavior of certain of its own disciples. This is never more true than when it is striving, in the purest and most disinterested spirit, to promote the welfare of society. A kind of antagonism is aroused and kept alive in the public mind, which is not less prejudicial to the public than unjust to medicine. The free progress of science is always sure to advance the interests of humanity. Society but wounds itself when it seeks to discredit the teachings of science, by setting against the comprehensive and well-weighed decisions of her true representatives, the crude opinions and hobbyistic dogmas of men whose perceptions are dimmed by the gloom of the den in which they think and move.

The editorial refers first to an earlier case that aroused their ire and then proceeds to the subject at hand.

We have another example in the conduct of the Committee on the Public Health and Nuisances Removal Bills, now before Parliament. It is known that these bills have encountered formidable opposition from a host of "vested interests" in the production of pestilent vapors, miasms, and loathsome abominations of every kind. These unsavory persons, trembling for the conservation of their right to fatten upon the injury of their neighbors, came in a crowd, reeking with putrid grease, redolent of stinking bones, fresh from seething heaps of stercoraceous deposits to lay their "case" before the Committee. They were eloquent upon the health-bestowing properties wafted in the air that had been enriched in its playful transit over depots of rotten hones, stinking fat, steaming dungheaps, and other accumulations of animal matter, decomposing into wealth, such as the imagination shrinks from picturing, and which language cannot describe. The Committee had before it a soap-boiler...this tallow-chandler had the misfortune to grow rich; the insane ambition of retiring seized him; he sold his business, and bid adieu to happiness, until he had negotiated with his successor, at the cost of two hundred a year, for the privilege of assisting on melting-dais! Mr. Archibald Kintrea (why should his name not live?) is a soap-boiler. He denies that soap-boiling produces disagreeable effluvia; he "rather likes it himself;" nay, more, "he means to say, that people generally enjoy it" -- ladies especially. And as to its being prejudicial to health, he only knows, that whilst he and his children lived upon the premises, they reveled in exuberant health, and have fallen off since they left. The fact is, it is all a matter of association or of fashion. The odor of putrefying fat is not only salubrious, but agreeable, if you can only make up your mind to discard vulgar prejudices.

Some ladies live in an atmosphere of Eau de Cologne or Rimmer's Vinegar; others -- Mr. Kintrea's fair friends -- dote upon the delicious fragrance of the copper "when the soap-boiling is going on with intensity."

But Mr. Kintrea and his colleagues do not rely upon these acts alone. They have "scientific" evidence! They bring before the Committee a doctor and a barrister. They have formed an Association. They have a Secretary, a bone merchant, who has read the writings of Dr. Snow. Now, the theory of Dr. Snow tallies wonderfully with the views of the "Offensive Trades Association" -- we beg pardon if that is not the right appellation -- and so the Secretary puts himself in communication with Dr. Snow. And they could not possibly get a witness more to their purpose. Dr. Snow tells the Committee that the effluvia from bone-boiling are not in any way prejudicial to the health of the inhabitants of the district; that "ordinary decomposing matter will not produce disease in the human subject." He is asked by Mr. Adderley (of the Committee), "Have you never known the blood poisoned by inhaling putrid matter?" (Snow's response) "No; but by dissection-wounds the blood may be poisoned." (Adderley asked) "Never by inhaling putrid gases?" (Snow responded) "No; gases produced by decomposition, when very concentrated, will produce sudden death; but when the person is not killed, if he recovers, he has no fever or illness."

Dr. Snow next admits that gases from the decay of animal matter may produce vomiting but says this would not be injurious unless frequently repeated.

Is this scientific evidence? Is it consistent with itself? It is in accordance with the experience of men who have studied the question without being blinded by theories?

Let it first be observed that Dr. Snow admits that the gases from decomposing matter may kill outright -- a pretty convincing proof of their potency. He also admits that in a less concentrated form they may cause vomiting. And here he stops, assuring us, that if the don't kill us, or cause repeated vomiting, they do us no harm. Now, as a matter of mere reasoning, we think the conclusion inevitable, that agents capable, when in a certain degree of concentration, of killing or causing vomiting, will in a lesser degree of concentration, also act on the animal economy; albeit in a less sudden and perceptible manner. It will be very difficult to persuade us that the long-continued action of gases known to have such lethal powers, if concentrated, is not injurious to health, when in a state of dilution. We shall not easily be reconciled, on the assurance of Dr. Snow, to endure a leakage in our house drains.

After criticizing Snow, the editorial goes on to opine...

We have a strong conviction, that as soon as our noses give us intimation of a communication between those conduits of decomposing animal and vegetable matter and our dwellings, it is time to call in bricklayer and plumber. We decline to wait until repeat vomiting, or a sudden death amongst our children, satisfy us that the gases evolved are in a highly concentrated state. Our professional avocations have, indeed, frequently given us the opportunity of tracing failing strength, flabby muscles, pallid cheeks, lassitude of body and torpidity of mind to this cause. We have felt it our duty to urge removal from the houses so affected, when the drains could not be repaired effectively, and we have commonly been gratified by observing a restoration to bodily and mental vigor. And we presume that there is hardly a practitioner of experience and average powers of observation who does not daily observe the same thing.

The editorial next addresses Snow's views of cholera and seems skeptical of the germ theory and supportive of the miasma theory.

Why is it then, that Dr. Snow is singular in his opinion? Has he any fact to show in proof? No! But he has a theory, to the effect that animal matters are only injurious when swallowed! The lungs are proof against animal poisons; but the alimentary canal affords a ready inlet. Dr. Snow is satisfied that every case of cholera for instance, depends upon a previous case of cholera, and is caused by swallowing the excrementitious matter voided by cholera patients. Very good! But if we admit this, how does it follow that the gases from decomposing animal matter are innocuous? We cannot tell. But Dr. Snow claims to have discovered that the law of propagation of cholera is the drinking of sewage water. His theory, of course, displaces all other theories. Other theories attribute great efficacy in the spread of cholera to bad drainage and atmospheric impurities. Therefore, says Dr. Snow, gases from animal and vegetable decompositions are innocuous! If this logic does not satisfy reason, it satisfies a theory; and we all know that theory is often more despotic than reason. The fact is, that the well whence Dr. Snow draws all sanitary truth is the main sewer. His specus, or den, is a drain. In riding his hobby very hard, he has fallen down through a gully-hole and has never since been able to get out again. And to Dr. Snow an impossible one: so there we leave him.

In that dismal Acherontic stream is contained the one and only true cholera germ, and if you take care not to swallow that you are safe from harm. Smell it if you may, breathe it fearlessly, but don't eat it.

Now we do not think it necessary to prove, by adducing evidence in opposition to Dr. Snow, that decomposing animal and vegetable matters are injurious to health. They ought not to be suffered to be stored in inhabited localities. We are not acquainted with a single medical practitioner of established reputation who would not consider that the removal of deposits of decomposing animal and vegetable matters was an essential condition for the improvement of the health of towns. We have adverted to the evidence of Dr. Snow, for the purpose of repudiating it as the expression of the teaching of medical science. ...The Committee seems to have contented itself with listening to the statements and objections of those who are interested in opposing the Bills. Those objections it was of coarse bound to hear. If it did not for any scientific evidence in reply, we hope it was because the statements of the dirt-and-effluvium-interest contained their own refutation.

The editorial goes on to support Dr. William Farr, a firm believer at that time in the miasma theory of cholera, and an early user of existing mortality data to guide public policy.

The only thoroughly scientific witness examined was Dr. Farr, and his evidence bore upon a totally distinct question. He did not deal with the causes of mortality, but with the rates of mortality in different districts. The facts he adducted went to prove that there is a natural mortality which does not exceed 17 in 1000; that whensoever that rate is exceeded there are noxious and generally removable causes in operation, and therefore that any excess of deaths above this proportion ought to be the signal for applying the resources of science to the improvement of the health of the district. In the original Public Health Bill it was proposed that a mortality of 23 in 1000 should warrant the extension of the Act to any locality. After hearing the objection of the great Bone and Stench interest, and the evidence of Dr. Farr, which proves to demonstration that anything over 17 in 1000 is unnatural, the Committee has amended the Bill by raising the rate which shall bring the Board of health into action to 27 in 1000! Verily the Committee has small faith, or little courage.

We shall review this branch of the subject next week.

In a follow-up editorial of June 30, 1855, The Lancet went on once more to deride Dr. Snow ("retained by the great dirt and effluvium interest") and support Dr. William Farr ("the accomplished head of the Statistics Department of the Register Office") and his use of mortality statistics to identify districts where death levels are abnormally high, requiring attention and intervention.

Legislative Outcome

A third hearing for the Nuisances Removal and Disease Prevention Act was held in July 1855. The bill underwent considerable revision, including changes as supported by John Snow (but opposed by The Lancet) that were favorable to those supporting the germ theory of disease, and became law on August 14, 1855. Manufacturers were not required to alter their aerial discharges and thus found much to like in the new law.

ONE YEAR LATER: JOHN SNOW'S SCHOLARLY RESPONSE

The Lancet July 26, 1856, pp. 95-97, by John Snow, M.D.

The science of public health, like other branches of knowledge, may be as much benefited by the removal of errors which stand in the way of its progress as by direct discovery; and it is with this conviction that I send for publication the result of an examination into a portion of the Registrar General's very valuable Weekly Returns of Deaths in London. Whilst a number of eminent authors have for a long period attributed the generality of epidemic or zymotic diseases to special poisons passing in some way from one patient to another, an active section of the profession has attributed the greater number of these disease to a variety of general causes, and in particular has asserted that they were occasioned, or greatly aggravated, by offensive gases proceeding from putrefying materials, even though these materials did not proceed in any way from sick persons.

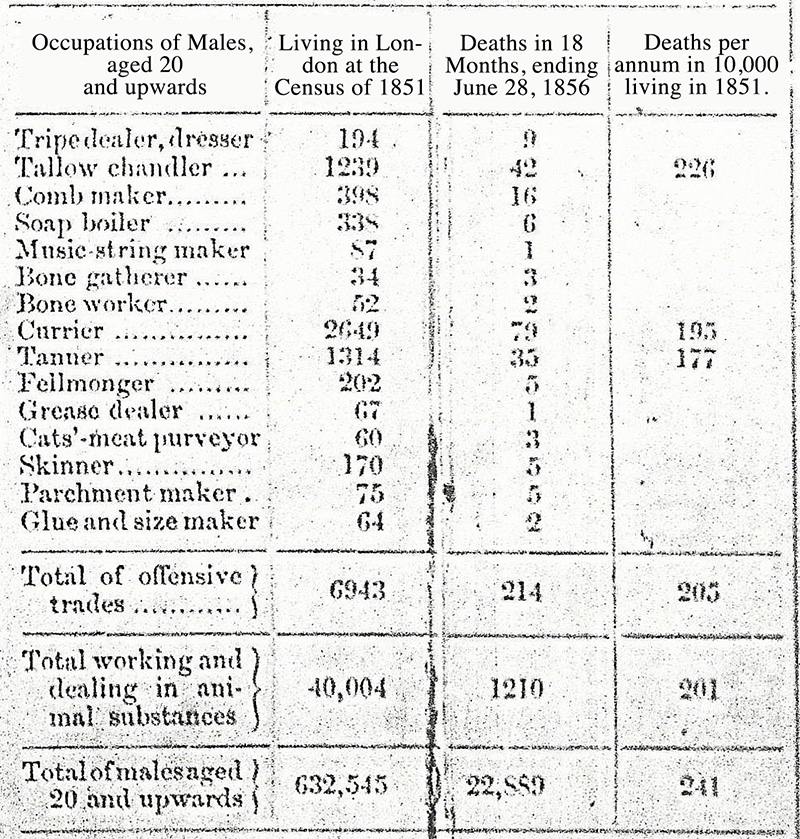

An opportunity is now afforded of examining this question on, as I believe, a larger scale than previously. For the last eighteen months the Weekly Returns of the Registrar General have contained the occupations of males aged 20 years and upwards whose deaths have been registered, and at the end of each quarter of a year the aggregate results have been given in a table. The causes of death are not contained in the table; but the diseases which offensive trades are presumed to promote are such as would increase the mortality, and in fact the mortality of persons in any occupation is the best criterion of its salubrity. The entire number of males aged 20 years and upwards in the metropolis at the last census was 632,545, and the number of deaths in this division of the population, in the year and a half just expired, was 22,889, being at the rate of 241 per annum in 10,000. The number of persons aged 20 years and upwards working and dealing in animal substances was 40,004 in 1851, and the number of deaths in the last eighteen months, 1210, being at the rate of 201 per annum in 10,000, or five-sixths as many as in the entire male population of 20 years and upwards. The greater number of persons working and dealing in animal substances are, however, occupied amongst silk, wool, and hair, which are in no way offensive; and I therefore thought it desirable to separate those trades which I believe to be really offensive, and I have included in the accompanying table all such occupations in which any death has occurred during the last six quarters. These occupations include 6943 persons, of whom 214 died, being at the rate of only 205 per annum in 10,000, which is greatly below the mortality of the whole male population of 20 years and upwards. There are some offensive trades in which no death occurred during the last eighteen months. If these trades had been included in the table, the mortality would have been shown to be lower than it appears. Butchers, poulterers, and fishmongers have sometimes been considered to follow offensive trades; but although these persons may occasionally, by a neglect of their duty and interest, be exposed to offensive gases, their proper occupations cannot be considered offensive, and I have therefore not included them in the table.

The Registrar General has very properly remarked that "As the persons engaged in various callings are distributed in different proportions through several periods of life, and as the rate of mortality depends on age, an analysis of the ages of the living and dying must be made before deductions regarding the comparative salubrity of professions can be drawn with safety." In comparing the mortality of a single occupation, or any group of occupations, with that of the whole population, however, one acts as if all the persons in these occupations had entered them before the age of 20; and therefore any fallacy from the above cause tells against the occupations examined, and not in their favour. For instance, according to the figures in the above table, the expectancy of life for the whole male population of London, at the age of 20 years, is 41 4/10 [?] years, or, in other words, the average duration of life in those persons would be over 61 years; whilst in the persons engaged in the offensive trades enumerated in the above table, the expectancy of life at 20 would be over 48½ years, and the average duration of life over 68½ years; but if some persons enter these trades later in life than 20 years, then the expectancy of life at 20 is greater, and the average duration of life is greater in those who arrived at 20. The mortality amongst the licensed victuallers and beershop-keepers has been at the rate of 373 per annum in 10,000 during last eighteen months; but part of this high mortality is undoubtedly due to the circumstance that a great number of persons do not enter these trades till they are advanced much beyond twenty years of age. All these facts tend to show that if the above table does not express accurately the morality of persons engaged in offensive trades, it errs by making the mortality appear greater, and not less, than it really is. I am quite aware that, as time rolls on, the returns of the Registrar General will afford a greater body of facts regaling offensive occupations; but, during the six quarters that have already elapsed since these returns were commenced, the results have been pretty uniform, and are, in my opinion, sufficiently important to be commented on. The health of persons employed in any occupation is necessarily the best measure of the effects of any such occupation on the public health. As the gases given off from putrefying substances become diffused in the air, the quantity in a given space is inversely as the square of the distance from their source. Thus, a man working with his face one yard from offensive substances would breathe ten thousand times as much of the gases given off, as a person living a hundred yards from the spot. Currents of air would make a difference; but this would be the average proportion of the gases inhaled respectively by the two individuals. There are, moreover, so many causes which influence the health of a neighbourhood, that it would be almost impossible to judge from that alone of the effect of trades or occupations conducted in it. I of course attribute no benefit to offensive smells; and the reason why the persons employed in the callings I am treating of enjoy a greater longevity than the average, is probably because they are less exposed to privation and less addicted to intemperance than men following many other occupations, and because, as a general rule, they do not lead a sedentary in-door life. It is sometimes argued, that since the gases given off during putrefaction are capable of causing death when in a somewhat concentrated form, they must necessarily be injurious in the most minute quantity; but this by no means follows: for carbonic acid gas, which is a well-known poison when present in large quantity, is a natural consistent of the atmosphere; vapour of ammonia is sniffed without hesitation, and even sulphuretted hydrogen is absorbed, in considerable quantities, by the visitors at Harrogate and some other watering places.

Cholera has not been present during the eighteen months for which the mortality in different occupations has been published; but there are certain facts which bear on the alleged influence of offensive trades on this disease. A great number of skin yards, bone boiling establishments, and other offensive factories are situated in that part of Lambeth which extends by the river side from Westminster-bridge to Vauxhall-bridge, and constitutes the sub-district called Lambeth Church, 1st part. This part of Lambeth contains also many of the other conditions which are supposed to, or which really, promote the prevalence of cholera. It is crowded with a poor population, wherever the ground is not occupied with the factories above mentioned, and it lies by the river-side, at an elevation of only two feet above Trinity high-water mark, yet the deaths from cholera in 1854 were only 29 to each 10,000 inhabitants, whilst in London at large they were 45 in 10,000; in the sub-district of Kennington, 1st part, less densely inhabited, they were 126, and in Clapham 103 in 10,000, the latter being a genteel, thinly inhabited sub-district, at the elevation of 21 feet. Again, the sub-district of Saffron-hill, with the slaughter-houses, knackers' yards, and catgut factories of Sharp-alley on its eastern boundary, and the Fleet-ditch, at that time uncovered, flowing through it, suffered in 1854 a mortality from cholera of only 5 in 10,000; being one-ninth of that of the metropolis generally, and one-twelfth of that of the Belgrave sub-district, where the mortality was 60 in 10,000. These circumstances might be thought to prove a little too much, were it not that the prevalence of cholera is influenced by a variety of circumstances, and in London very much by the nature of the water supply; for, in the short but severe epidemic of 1854, the chief medium of its propagation in the metropolis was water, containing whatever passed down the sewers from previous patients. The sub-district of Bermondsey, called the Leather-market, which contains a number of factories for skin-dressing, suffered, in 1854, exactly the same high mortality as the other five sub-districts in the South division of London, which, like it, were supplied exclusively with the impure water of the Southwark and Vauxhall Company. The conclusion to be drawn from all these facts is, that the vicinity of offensive factories leaves the cholera to pursue the same course that it would do in their absence.

Sackville-street, July, 1856.

No Response by Thomas Wakley to Snow's 1856 Rebutal Article

While The Lancet published John Snow's rebutal article to their two critical editorials (see above), The Lancet chose not to respond to the epidemiological findings Snow presented in the article. Instead, Thomas Wakley continued to express his disagreement with Snow, questioning in general his methodology and conclusions, while he offered full support for the prevailing miasma theory of cholera.

The Lancet's Ultimate Rath

When Dr. Snow died on June 16, 1858, The Lancet issued a short, terse notice of his death. They made mention of his work with anesthetic agents, but ignored his thoughts on the germ theory and enormous contributions to the epidemiology of cholera. Five months later, in reviewing Snow's book after his death (On Chloroform and other Anesthetics: Their Action and Administration), The Lancet stated, "On reading this memoir it occurs to us that it would have been only graceful and becoming if its writer had, at least, alluded to the active part taken by The Lancet, in bringing Dr. Snow's merits before the professional world at a time when such an encouragement was all-important to him -- when he was comparatively unnoticed and unknown, and struggling at the painful commencement of what must always be an arduous career." The Lancet seemed resentful of John Snow's success, perhaps still focusing on Snow's 1855 testimony which disregarded their favored miasma theory.

Or perhaps Thomas Wakley continued to be irritated by Snow's earlier use of chloroform with Queen Victoria during the birth of Leopold in 1853 with the full support of the Queen and husband Prince Albert, followed a second time at the birth of Princess Beatrice in 1857. All these irritations likely surfaced when John Snow died on June 16, 1858. The forth-coming obituary from The Lancet was terse, mentioning his work with anesthesia while completely omitting his enormous contributions to the field of epidemiology as a scientific method for challenging the erroneous miasma theory, decades before the causative organism (i.e., Vibrio cholerae) was finally identified. The considerable obituary slight was eventually addressed by The Lancet, but following a delay of 155 years, published in 2013.

Modern Thinking

It is now clear that diseases are caused by various factors including microbial agents (as stated by the germ theory) and environmental pollutants (as supported by the miasma theory). Snow appeared to have extended his theories on the microbial origin of cholera to other diseases, and refused to consider that fumes from bone-boiling factories or similar establishments could cause ill health but not mortality. In the absence of knowledge and full scientific data, all sides testifying on the Act seemed to rely on intuition and even emotion, including advocates of the germ theory, supporters of the miasma theory, and The Lancet which seemed strangely moralistic and intolerant in its editorial attitude towards John Snow.

Sources:

Editorial. The Lancet 1, 634-5, 1855.

Editorial. The Lancet 1, 649-650, 1855.

Editorial Book Review. The Lancet 2, 555-556, 1858

- Lilienfeld

D. American J Epidemiology 152(1), 4-9, 2000.