Seven Days from Symptoms to Death

On June 11, 1858, John Snow exhibited symptoms that would soon lead to his death. Seven days later his life was over. What happened during those seven days?

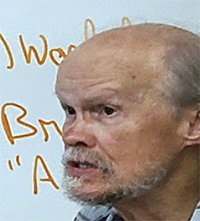

To answer that question, we turn to Peter Vinten-Johansen Ph.D. a leading expert on the life and times of John Snow. He is currently Associate Professor Emeritus of History at Michigan State University; lead author of Cholera, Chloroform and the Science of Medicine: a Life of John Snow (2003) - the most comprehensive book ever written on John Snow; content manager of the highly informative web site John Snow Archive and Research Companion; and historian of mid-nineteenth century English cholera epidemics.

Rather than sparely listing the few facts that are available on the last days of John Snow, Vinten-Johansen has been experimenting with narrative history that combines facts with reflection, inclusion and interpretation. An example is the seven pre-death days, included below.

Source: Vinten-Johansen, Peter. The death of John Snow -- an experiment in narrative history, Preprint, 2020.

What follows are the pages written by Peter Vinten-Johansen [with a few additions in brackets by Frerichs] that address the final days of John Snow's life.

[DAY 1 - THURSDAY, JUNE 10TH]

He lay on the floor, beside his chair and partly under the writing table, attempting in vain to regain his seat. Right arm and leg moved jerkily. Left arm and leg were completely limp. He turned his face toward her as she entered the room. His mouth was strangely drawn to the side and drooping. Yet his speech was surprisingly distinct. It’ll surely pass, he said. There’s no loss of feelng in the limp side, so the paralysis must be temporary. Should resolve on its own, as before. But admittedly, never experienced anything this severe. No! No! Absolutely no reason to send for Dr. Budd. Yes, he lives close by, but it’s unncecessary. Just need assistance onto the couch. And kindly fetch the anesthetist’s kit from the surgery. Must dull these searing chest and stomach pains, somehow.

Wetherburn [longterm housekeeper, Jane Wetherburn] went back downstairs to the surgery and returned with a black case. She had observed him use various apparatus on occasion during self-experimentation, so she felt confident to assisting according to his directions.

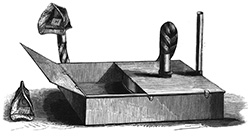

He asked for ether. The flavor was more to his liking than chloroform, the sensations more pleasurable, and the dosage was easier to control. Use the portable ether inhaler — that shiny, black metal box the size of a thick book at the bottom of the kit.

It seemed surprisingly light until she realized it was made of tin covered in japan varnish. She placed the box on an end table near his head, opened the left side and extracted an elastic tube about three feet long with an attached face-piece and a thin brass tube.

She poured water into the now empty left chamber until it was three-quarters full. On the top of the apparatus, at the far right, was a small opening; Wetherburn carefully poured two ounces of sulphuric ether from a bottle into the chamber below, then fitted a brass tube into the opening. The elastic tube with the face-piece screwed onto an opening in the center of the ether chamber. She looked up, expectantly.

He had regained full control of his right side. He asked for the face-piece, used his good hand to position it over mouth and nostrils, compressed the leaden edges for a snug fit, completely opened the expiratory valve with a deft finger-flip, closed his eyes, and began inhaling. Every half-minute he gave the valve a nudge until it was nearly closed, all the while inhaling until fading consciousness signaled him to pull away the face-piece. He waited until the effect had almost worn off, then resumed inhalations.

Wetherburn remained at hand, occasionally refreshing the apparatus with ether and water. The ether had the desired immediate analgesic effects, but his stomach discomfort worsened as the day wore on. The evening seemed endless, followed by an interminable, sleepless night, he on the sofa, she in a chair nearby.

[DAY 2 - FRIDAY, JUNE 11TH]

At first light Friday morning, he vomited what must have been yesterday morning’s breakfast, for he had eaten nothing since. Wetherburn observed streaks of blood in the bowl. Time to send for Dr. Budd.

* * *

John Snow’s personal physician was puzzled. The patient presented complete muscular paralysis on the left side. Yet a few pricks with a dull hat pin confirmed Snow’s assertion that sensation was normal on the affected side. A strange form of partial paralysis. Still tenderness in the epigastrium after twenty hours. No vomiting until this morning, but now persistent with some hæmatemesis [or hematemesis, refers to the vomiting of blood] ― the sign that had prompted the house-keeper to contact him.

George Budd needed more information. Still passing water? Wetherburn extracted a graduated urinal from under the couch. It was the volume Budd expected from someone who had had nothing to eat and little to drink for many hours. He carried the urinal to one of the southwest facing windows, and lifted it to the light. Clear, albeit on the dark side; probably due to a limited fluid intake. No grossly observable hæmaturia. He returned to the couch and gently probed both of Snow’s legs with his fingers; no evidence of dropsical swelling. Encouraging. His first hunch, renal failure, was no longer a certainty. Nonetheless, Budd poured a few ounces of urine from the urinal into a tube, pushed in a cork stopper, and placed the sample inside his waistcoat. He would test for albuminuria later.

He chatted a few moments with his patient. The symptoms were very peculiar. Baffling, frankly. Another opinion would be helpful. Snow agreed.

Charles Murchison, M. D. of Upper Seymour Street, Portman Square [a prominent physican, known for his expertise on fevers and diseases of the liver] met George Budd at his surgery in Dover Street, Piccadilly and the two walked the half-mile to 18 Sackville Street. Snow was still on the couch, paler than before, but his pulse and breathing remained normal. The atypical paralysis was unchanged. Snow was unable to move anything on the left side, yet sensation remained intact everywhere.

Murchison began by taking a brief patient history, focusing initially on any similarities to current symptoms. Snow admitted to occasional vomiting the last few years, sometimes with hæmatemesis. They were mere annoyances, he insisted, always minor and of short duration, and there had been none of late. Just some numbness in the hands and feet, episodically, in the last half year. A touch of vertigo last December which vanished after twenty-four hours couch-rest. Had severe headaches three weeks ago; simple neuralgia, probably, since it was self-treated with good effect.

Murchison shifted ground to complaints of longer standing.

Snow recalled a couple minor indispositions. Had a touch of phthisis pulmonalis [an older term for pulmonary tuberculosis] about seven years ago, contracted whilst attending at the chest hospital in Brompton [The Hospital for Consumption and Diseases of the Chest, appointed physician during 1851-1852]; it cleared up in short order after lengthening the daily walk regimen. Kidney stones one summer, about fifteen years ago; sorted by a rest cure in the country and dietary changes.

What changes?

Some beef now and then. A glass of port or red wine in the evening. No re-occurrence of the complaint since. Been in fine fettle, really, in the days leading up to yesterday’s incident.

Budd and Murchison had retreated to the parlor to discuss their findings. They quickly ruled out phthisis. The attack was too sudden, and Snow’s constitution wasn’t consumptive in the least. Soon settled on apoplexy, but kind, cause, and severity were uncertain. His symptomatology flummoxed them. Their conversation turned to a diagnostic differential.

Could be Hæmorrhagie cerebrale [a type of hemorrhagic stroke]. Loss of motion suggests pressure on the motor control part of the brain from sudden extravasation of blood serum into the brain.

The pale countenance fits. But in typical serous effusion into the brain the pulse is feeble and his is normal.

OK, but something is impinging on the motor area controlling his left side. Could be turgescent blood vessels? [blood vessels that are swollen or distended].

Perhaps. The pulse is definitely strong, but then his features should be flushed, and there’s no sign of that.

Still think it’s some form of hæmorraghic apoplexy [an older term that typically refers to a cerebral hemorrhage, leading to a sudden neurological impairment].

But there is no diminution of sensation, his reasoning is clear as a bell, and he’s never lost consciousness, even momentarily. Snow’s dodgey kidney history can’t be ignored. Could be cerebral complications from Apoplexia renalis [spontaneous, non-traumatic acute renal hemorrhage].

If so, would have expected evidence of dropsy by now, but that would be the best outcome. Cerebral apoplexy is generally fatal in people over the age of thirty-five.

Self-reporting is all well and good, but Snow may be playing this hand too close to the vest. He’s convinced himself it’s something minor. Need to talk with the housekeeper in private.

Wetherburn joined the physicians in the parlor. Was there anything she could tell them that had not come out upstairs?

Yes, the morning of the attack. Dr. Snow seemed unsteady on his feet when descending the stairs from his bedroom. Had said he felt a mite giddy, and then proceeded to lie on the couch. Several minutes later, he arose, and walked around the morning room a few times.

To what effect? Steadily or unsteadily? Seemed normal enough. Said he was hungry. Walked into the adjoining dining room, ate his usual breakfast, then returned to the morning room.

The couch?

No, to his writing desk.

When did the attack occur?

Shortly thereafter. Heard him fall while downstairs in the scullery [utility room, located adjacent to the bottom floor kitchen], and was with him less than a minute thereafter.

Did he have convulsions?

No. But jerky motions on the right side at first.

What about the left side?

Couldn’t move his left arm or leg a’tall. And, come to think, his mouth was crooked, drooping-like.

The left side of his mouth? Hmm!

Yes, must ha’ been.

Did he ever lose consciousness?

Not that Wetherburn had noticed.

Budd and Murchison had a few more questions for the housekeeper.

Did she remember any problems with his health prior to yesterday morning, other than what Dr. Snow had already told them?

Yes, he neglected to mention that, five years ago, he was too ill to sit up or write for many weeks.

Nothing else from long ago comes to mind.

Anything within the previous year he failed to mention?

He spent much of last summer in the countryside, which was very unusual.

Anything else?

Not that she could think of.

The housekeeper’s comments were suggestive. Thursday’s episode may have been the latest in a series of apoplectic attacks, albeit all transient and minor until this one. For Snow’s current condition struck them as more serious than anything he or the housekeeper had described happening in the past.

On the other hand, Snow might be correct: nature would restore his system, as it had done before, with little or no medical assistance. He was an excellent clinician, but this time he was the patient. Going for him was the fact that he was only forty-five and in good health, all things considered. Since he was a man of temperate tastes and habits, there was nothing for them to recommend at this stage but patience, rest, and hope.

* * *

[DAY 3 - SATURDAY, JUNE 12TH]

Wetherburn noticed definite signs of improvement during the weekend.

Snow’s vomiting tapered off Saturday morning; and when it did occur, there was no blood in the basin. He continued to be discomforted by frequent retching, however. Persistent hiccups, but he didn’t seemed overly bothered by them. The fine weather of late continued throughout the day, with outdoor temperatures in the upper 60s, as much as ten degrees warmer in the morning room when the afternoon sun came through the three large windows at the front of the house. Snow lay there on the couch the entire day, during the night as well.

[DAY 4 - SUNDAY, JUNE 13TH]

Dr. Budd stopped by on Sunday morning. He was concerned about potential albuminuria [the presence of abnormally high levels of albumin in the urine; albumin is a protein that is normally found in the blood, and its presence in the urine can be an early indicator of kidney damage]. When he had heated a teaspoon-full of Snow’s urine from Friday’s sample, it turned opaque just short of the boiling point. So Budd immediately checked Snow’s ankles and fingers for signs of swelling, but found none. Good; still no indications of dropsy [an outdated term referring to the abnormal swelling of tissues due to excess fluid]. He now wondered if this stroke, too, would turn out to be a minor one.

[DAY 5 - MONDAY, JUNE 14TH]

Snow’s spirits soared over the next twenty-four hours. He fantasized about resuming his anaesthetic practice within a fortnight. Vomiting and hiccups had ceased by Monday morning. Snow asked Wetherburn to make inquires for someone to jerry-rig him a portable writing desk; James Ball’s shop in Bryanston square could certainly do it. Just a temporary measure until full motion is regained. Must finish inhalation anesthesia by the end of the month. John Churchill is expecting the last few chapters.

Wetherburn permitted herself to feel hopeful for the first time since Thursday morning.

But then she caught herself. Was he just lying there on the couch, building castles in the air?

* * *

Snow crashed a few hours later. Wetherburn sent for Dr. Budd as soon as she saw a turn for the worse.

He took Snow’s pulse; it was racing, but still strong. His breathing was rapid and shallow.

[DAY 6 - TUESDAY, JUNE 15TH]

Dr. Murchison came as well. There was nothing they could do for him. The two physicians returned on Tuesday. The weather had turned unseasonably warm; already ninety degrees in the shade, and well over 100 degrees in the direct sunlight bathing the front of 18 Sackville Street.

Snow’s face, hands, and feet were now swollen and crimson. While the heat and south-easterly winds carrying sewage odors from the River Thames certainly added to Snow’s discomfort, they had not caused this change in his condition and the livid complexion. The latter was the first unmistakeable sign of serous effusion – plasma was leaking from Snow’s capillaries. His pulse had turned feeble. His mind was wandering. Time had resolved medical uncertainty, as they knew it would, but not in the way they had hoped. When should he be told? Not today. Snow’s still mumbling about a full recovery. Pricking that bubble would be cruel and unnecessary.

But the two physicians decided to inform the housekeeper that her master was dying. It’s now evident that Thursday morning’s attack was a severe stroke. Best guess is that partial renal failure brought it on, based on the traces of albumin detected in his urine. Dr. Snow’s kidneys did rally for a time, which explains the turn for the better, but they must be too damaged to make a proper job of it for his life to continue. Ever so sorry. In that case, there were things she must now do. Would one of them kindly walk home via Piccadilly to the round-about at Regent’s Street, where the messengers wait for a hire. Ask one of them to come immediately to the house. She would have a message ready to be carried to a telegraph clerk at the Birmingham Railway Depot in Euston Square. The housekeeper accompanied the two physicians to the front door, then walked through the parlor into Dr. Snow’s surgery. She located the necessary form, and began writing a telegram:

Reverend Thomas Snow, Greetland

Halifax, Yorkshire.

* * *

Jane Wetherburn returned to the morning room, where Snow was sleeping on the couch. She looked fondly at the man she had served for twenty years, the last six at Sackville Street. Just the two of them. She was housekeeper in name, majordomo in actuality. She would miss him immensely, but the future gave her no worry. Dr Snow had shown her the will he had prepared the year before. In the event of his death, his executors were instructed to purchase bonds of sufficient value to provide her an annual annuity of £20 for the rest of her life. A modest amount to put aside for her old age if she continued in service elsewhere in London, sufficient for her needs if she decided to retire to Berwick [a small village in East Sussex, south of London.] She would be required to stay on here for awhile in any event. There were Snow’s books and papers to sort. Most immediately, she must begin readying rooms for family members arriving from Yorkshire for the funeral.

* * *

Reverend Snow [John Snow’s younger brother Thomas Snow by 8 years] boarded a train on the London and North Western Railway, bound for London, Euston Square.

* * *

Snow remained conscious, albeit with delirious episodes, throughout Tuesday afternoon and well into the evening. Heat-lightning during the night, but no rain to freshen the city.

[DAY 7 - WEDNESDAY, JUNE 16TH]

On Wednesday morning, the 16th of June, Drs. Budd and Murchison told him that his condition was extremely grave. They did not think he would survive the day. Snow listened without comment. He then expressed his appreciation for their diligent attendance the last few days. Hopefully, they would not think it churlish or ungenerous of him to have Dr. Todd visit and render a third opinion. But it was too late for any more of that.

The death rattle began an hour before noon. If Bentley Todd, M.D., with premises near Grosvenor Square a half mile to the west, was sent for and actually came to 18 Sackville Street, he would have found Snow already in a coma.

John Snow died at 3:00 o’clock PM. Thomas Snow had arrived in time to be at the bedside when he drew his last breath.

THE AFTERMATH

Three days later, the autopsist transferred John Snow’s body to an undertaker at the Economic Funeral Company’s Baker Street location, north of Portman Square, where someone — perhaps the Reverend Snow — paid £5, 17 shillings, and 6 pence for a burial plot and interment. By then, obituary notices had appeared in the morning newspapers and two London medical journals. Also on Saturday, Thomas Snow walked several blocks south-west from his brother’s house to 8 Bury Street, where he found George Keith, Registrar for Births and Deaths in the St. James’s Square sub-district. Keith certified Snow’s death upon receipt of the autopsist’s post mortem report.

John Snow was interred at noon on Monday, the 21st of June, in the Brompton city cemetery situated between the Old Brompton and Fulham Roads, southwest of Kensington Gardens. The funeral was solely a family affair. Expansion of railway routes in the previous two decades certainly would have made it possible for his mother, two other brothers, and three sisters to travel from Yorkshire to London for the funeral, whether or not all of them actually made the journey. Surely, Uncle Charles Empson made the shorter train journey from Bath, if he was physically able, to say a final goodbye to a beloved nephew.

Was Jane Wetherburn allowed to attend? If so, she would have been the only outsider. None of the hundreds of medical men or dentists in metropolitan London with whom Snow had worked for over two decades were permitted to pay their respects. Nor did the Snows of Yorkshire allow any of Snow’s closest friends and colleagues to stand at the grave site. Not Peter Marshall. Not John French. Not even Benjamin Ward Richardson.

[THE END]

POTENTIAL FACTORS IN SNOW'S DEATH

DIET

The link between John Snow's diet and his state of health has been the subject of much speculation. At the age of seventeen, John Snow became a vegetarian and continued to abstain from meat for eight years. He had, however, supplemented his vegetarian diet with butter and milk. When others pointed out that he was not adhering to the regime of an absolute vegetarian, he proceeded to eliminate all animal products from his diet. He also had been a strong advocate of temperance, and was a total abstainer from alcohol. In 1836 he had joined the York Temperance Society, and remained a member of this organization until his death. He also in 1845 became the Honorary Secretary of the Medical Temperance Society of London, reflecting the strength and persistence of his views.

ILL-HEALTH

The health of John Snow had never been the best. After receiving in 1844 his M.D. from the University of London, Snow had suffered from a bout of tuberculosis of the lungs. He recovered by spending a good deal of time in the fresh air. In 1845 he had an acute attack of renal disease. His physician told him to abandon his strict vegetarian diet and to take wine in small quantities. He complied and thereafter his health was reported to have improved.

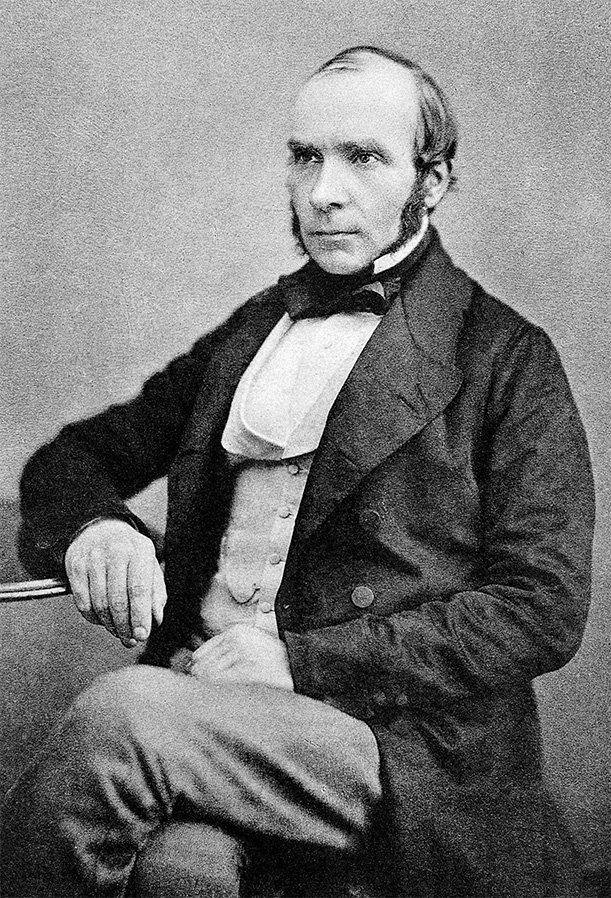

Likely of greater significance regarding his premature death at age 45 was his inappropriate use of anesthesia. Snow did frequent experiments with anesthetic agents upon himself at his home. He was the first to carry out experiments on the physiology of anesthesia, and did not spare himself in investigating every possible substance that might be employed as an anesthetic. The pathologic effect of most of these agents was not known in Snow's time.

Adding another clue to the cause of his early death is Snow's index finger on his right hand, which appeared in his 1857 photograph at left. Such swelling of the fingers has been associated with chronic renal failure. Exposure to anesthetic gases is now know to have numerous adverse health effects, including severe damage to the kidney. In John Snow's case, his swollen fingers were likely due to extensive self-experimentation over nearly a decade with a variety of anesthetic agents (e.g., ether, chloroform, ethyl nitrate, carbon disulfide, benzene, bromoform, ethyl bromide and dichloroethane).

For additional details on Snow's tell-tale hands, click below.

Mawson, A.R. The hands of John Snow: clue to his untimely death? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 63(6), 497-499, 2009 (PDF).

Mawson, A.R. The hands of John Snow: clue to his untimely death? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 63(6), 497-499, 2009 (PDF).

For more on addiction to chloroform in a contemporary of Dr. Snow and fellow pioneer in chloroform research, click below.

Defalgue RJ and Wright AJ. The short, tragic life of Robert M. Glover. Anaesthesia 59, 394-400, 2004.

Defalgue RJ and Wright AJ. The short, tragic life of Robert M. Glover. Anaesthesia 59, 394-400, 2004.

DEATH FOLLOWED BY AUTOPSY

On the evening of June 9, 1858, John Snow joined a small group of medical colleagues to discuss a new bi-aural (i.e., two ear pieces) stethoscope, and joined a committee to investigate the cause of the first heart sound (i.e., measure of systolic blood pressure

The next morning, he suffered a slight stroke while working on his monograph, On Chloroform and other Anesthetics.

He recovered sufficiently to pen a portion of his book, and had written almost to the end when he suffered another cerebral accident a few days later. His housekeeper found him on the floor, having lost all power over his left arm and leg, and his mouth appeared drawn to the right side. Fortunately, memory and consciousness were unimpaired until almost the end, which occurred at 3 pm on June 16,1858. His cleric brother Thomas, who just three months earlier had been appointed Head of the Greetland School in northern England, was visiting him when he died of stroke (i.e., "apoplexy") and renal failure, and registered his death on June 18, 1858.

At autopsy, Snow's kidneys were found to be "shrunken, granular and encysted." While there was also scar tissue in the kidney from old bouts of tuberculosis (believed to have occurred in his 20s), it is likely that his kidney problems arose from anesthetic experimentation, which subsequently caused his premature stroke.

On June 26, 1858, the following short notice of death appeared in The Lancet:

After Snow's death, a friend of long standing, Dr. Benjamin Richardson, edited and prepared Snow's manuscript for publication with John Churchill of London. On Chloroform and other Anesthetics, published in 1858, is now regarded as one of the first textbooks in the field of anesthesiology.

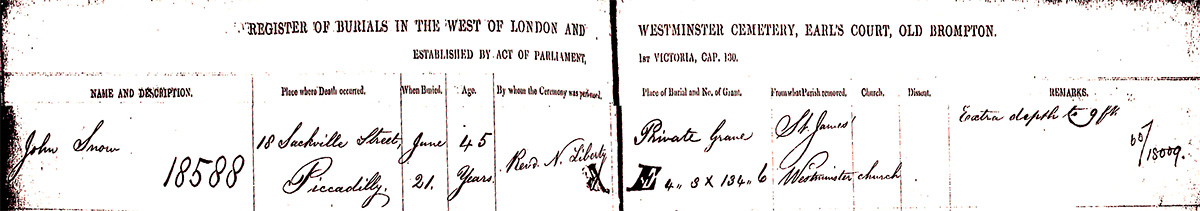

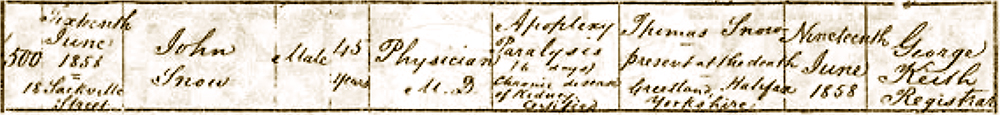

Snow's death certificate (see below) was filed on June 19, 1858, three days after his death, by Registrar George Keith. Ever since 1837, Civil Registration had begun in both England and Wales, with local registrars like George Keith being responsible for recording deaths in their area, as well as births and marriages. A copy of the certificate was then filed with the General Register Office (GRO) in London, where, along with every-ten-year population data [the most recent census being 1851], the officials used the cause of death, age, sex, occupation and home address to derive and publish area-specific mortality rates.

In addition to this standard information, John Snow's death certificate had two notable entries. First, it confirmed that his brother Reverend Thomas Snow was present at the time of his death, coming from Yorkshire. Having just been appointed three months earlier as Curate in charge of the Greetland School, he pushed his calendar aside and rushed to be with his older brother. Second, it clearly listed the cause of John Snow's death as paralysis following a stroke (apoplexy), with chronic renal failure cited as a contributing factor.

BROMPTON CEMETERY

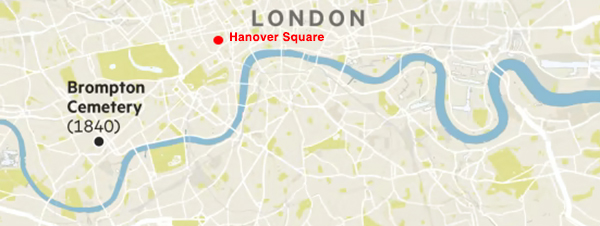

Snow was buried in London at the Brompton Cemetery, located a short distance, but north of the River Thames, from the Battersea site where the Southwark and Vauxhall Company (the object of his famous epidemiological investigation, entitled the "Grand Experiment") drew cholera-contaminated water from the River Thames.

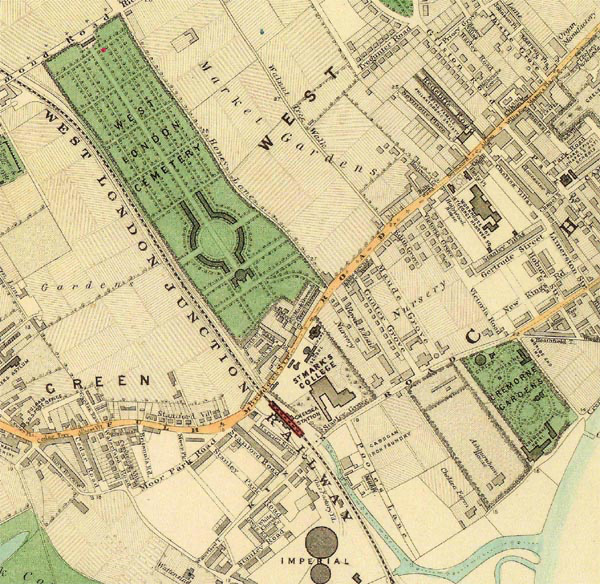

Shown on the map below is the location of the cemetery in relation to the Epidemiological Society of London by Hanover Square (red dot), where Snow was an active member until his death.

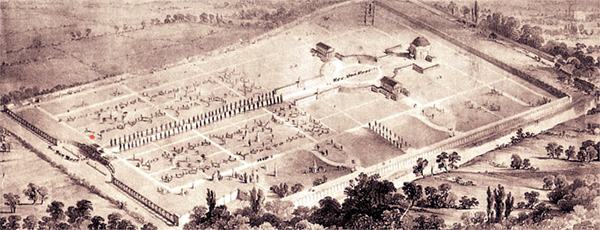

Brompton Cemetery was originally a private company having financial problems. In 1837, an Act of Parliment secured the rights to establish the Brompton Cemetery as a government entity and it was sold to the British government. All legal matters were finalized in 1839 and the cemetery officially opened in 1840.

It is now managed by the Royal Parks, a charity organization, and is considered one of Britain's oldest and most distinguished garden cemeteries.

It is here that John Snow was buried in a private grave in 1858 (see at right ). The view is of Brompton cemetery in 1840, with the North gate in lower left.

John Snow was buried in 1858 near the North gate (red dot).

The North gate of Brompton Cemetery in 1840 enters a path that goes the length of the cemetery. In the enlarged image of the North Gate area, to the left of the gate is the site where John Snow was buried in 1858 (red dot).

Source: Brompton Cemetery, 1840 in Thames R. Earl's Court and Brompton Past, 2000.

Brompton Cemetery in Stanford's 1862 map is shown as West London Cemetery (an earlier name before the 1840 change to Brompton Cemetery). John Snow's tombstone is shown as a red dot at the north end. The River Thames appears at the bottom right, along with an inland waterway that extends north towards the cemetery.

Source: Stanford's Library Map of London and its Suburbs. Published by Edward Stanford, 6, Charing Cross, London, February 15, 1862.

The West London and Westminster Cemetery Company had owned what became the Brompton Cemetery before the government assumed ownership in 1838. The name at the time was West London and Westminster Cemetery, still seen over the entrance on Old Brompton Road (i.e., the imposing North Gatehouse that was built to look like a triumphal arch), serving perhaps as a reminder of the past.

Three years later in the Old Ordnance map of 1865, the Brompton Cemetery is also erroneously shown as the earlier name, West London and Westminster Cemetery. The location of John Snow's tombstone is seen at the North end by the Richmond Road entrance (red dot). Fulton Road passes by the south entrance, while the West London Extension Railway passes on the west side.

Source: Old Ordnance Survey Maps -- Chelsea, 1865.

The North Gatehouse of Brompton Cemetery with the Old Name still at the Top

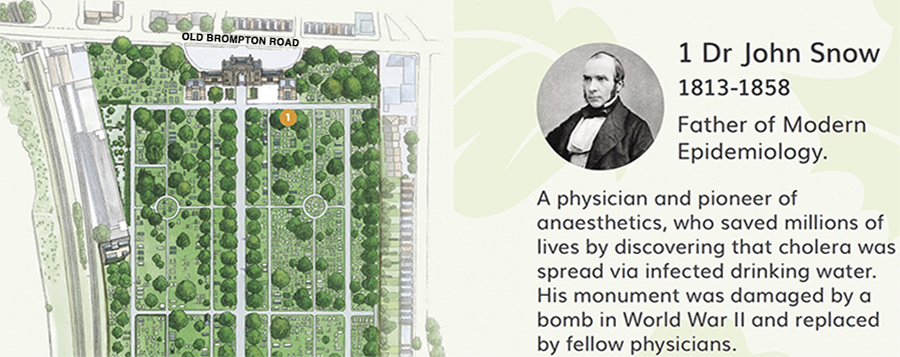

The Brompton Cemetery routinely lists its 100 most visited sites. Number 1 in 2025 was Dr. John Snow.

When selecting John Snow's tombstone, brother Thomas Snow and other family members likely picked a more modest size. They probably made their choice and then travelled back home, leaving the details to the Baker Street mortician.

As months went by, Snow's friend Dr. Benjamin Ward Richardson maintained contact with the family and with their support sent a notice to the British Medical Journal to asses if there was interest in funding a larger, more suitable monument. On May 21, 1859 the following appeared:

THE LATE DR. JOHN SNOW — A few professional friends have been kind enough to join with me in undertaking to place in the Brompton Cemetery, a plain but durable monument over the grave of the late Dr. Snow, as a last and fitting memorial of the esteem in which he was held by those of his professional brethren who had the pleasure of his friendship. Having ascertained that such mark of remembrance would be congenial to the feelings of Dr. Snow’s relations, I take the opportunity of making the project widely known through your columns , feeling sure that a great many members of the medical body will be glad to co-operate in paying this simple tribute to the memory of our late estimable and distinguished brother in science. A committee will be organized shortly to carry out this object to completion; meanwhile, subscription for the memorial may be forwarded to Dr. Hanksley, 26 George Street, Hanover Square, or to myself. B.W. Richardson, 12 Hinde Street, May 18, 1859.

The BMJ posting was successful, and soon his friends erected a suitable monument in Brompton Cemetery, which itself had a unique history.

The inscription started poorly with an error in his date of birth, listed as March 15, 1818 rather than March 15, 1813. The full text on the upper section of the monument read:

TO

JOHN SNOW, M.D.

BORN AT YORK

MARCH 15, 1818

IN REMEMBRANCE OF

HIS GREAT LABOURS IN SCIENCE

AND OF THE EXCELLENCE

OF HIS PRIVATE LIFE

AND CHARACTER

THIS MONUMENT

(WITH THE ASSENT OF

MR. WILLIAM SNOW)

HAS BEEN ERECTED OVER

HIS GRAVE

BY HIS PROFESSIONAL BRETHREN

AND FRIENDS.

The monument was restored in 1895 by Richardson and colleagues and then again in 1938, as described in the lower two sections:

RESTORED IN 1895

BY SIR BENJAMIN W. RICHARDSON, F.R.S.

AND A FEW SURVIVING FRIENDS.

INSCRIPTION RESTORED IN 1938 BY MEMBERS

OF THE SECTION OF ANAESTHETICS OF THE

ROYAL SOCIETY OF MEDICINE AND ANAESTHETISTS IN

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.

At the time of the 1895 restoration, Richardson was 67 years old. He died a year later on November 1, 1896.

In World War II, the monument was destroyed by a bomb during a 1941 air raid. In later years it was restored a third time, with the date of birth correctly shown as March 15th, 1813.

The post WWII inscription at the very bottom now reads:

THE ORIGINAL MEMORIAL TO JOHN SNOW WAS DESTROYED

IN ENEMY ACTION IN APRIL 1941. THIS REPLICA WAS

ERECTED BY THE ASSOCIATION OF ANAESTHETISTS OF

GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND IN SEPTEMBER 1951.

In back just to the right is the low tombstone of John Snow's uncle, Charles Empson, who died on June 25, 1861, three years after the death of his beloved nephew.

John Snow's grave, located near the Old Brompton Road Northgate entrance, is well-known to the gate-keepers of London's Brompton Cemetery.

BURIAL REGISTRY

The Record Room of the Brompton Cemetery contains the Burial Registry for most persons buried in the cemetery. John Snow is listed as entry 18588, with date of death and other related information, including his last address at 18 Sackville Street (see below).