Stream 2- Broad Street Pump Outbreak

e: Handle Removal, Index Case and Rev. Whitehead

THE IMMEDIATE NEIGHBORHOOD

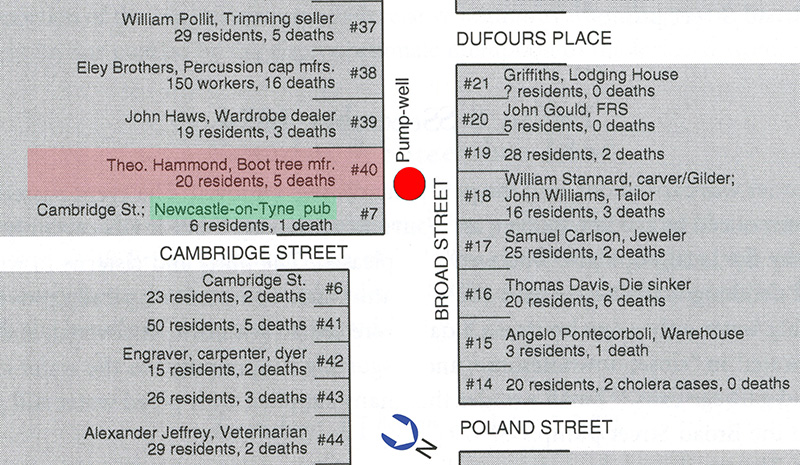

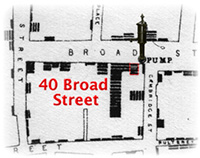

To become oriented in a new place, there is nothing like a map, in this case modified from a figure in Cholera, Chloroform, and the Science of Medicine, the definitive 2003 book on John Snow. The abbreviated map shows the southwestern portion of Broad Street encircling both the Broad Street Pump (red dot) and neighboring businesses, residents and deaths attributed to the Broad Street Pump outbreak. Two sites are especially notable, 40 Broad Street (in red) where the index case and her parents resided, and the Newcastle-on-Tyne Pup on Cambridge Street (in green), built in the 1870s, long after John Snow's death. It was renamed the John Snow Pub in 1954, still famous along with replica of the handle-free pump to aficionados of John Snow.

Of course there are two name changes, Broad Street is now Broadwick Street and Cambridge Street is now Lexington Street.

When standing by the Broad Street pump or coming out the front door of the index case at 40 Broad Street, the building at 18 Broad Street is right across the street. Further information on the index case is presented below.

Source: Modification of: 16-21 Broad Street, 1854, (currently 48-58 Broadwick Street). Sheppard, Francis. Survey of London, 31 (2), p. 216.

REMOVAL OF THE PUMP HANDLE

Dr. John Snow is credited with taking bold action when he sensed that contaminated water from the public pump on Broad Street was the cause of deadly cholera during the 1854 outbreak in London. Here is what he wrote of his legendary action on September 7, 1854.

HANDLE OF THE BROAD STREET PUMP

"I had an interview with the Board of Guardians of St. James's parish, on the evening of Thursday, 7th September, and represented the above circumstances to them. In consequence of what I said, the handle of the pump was removed on the following day."

- John Snow in his 1855 book

So who was the parish Board of Guardians and why did they respond as they did to Dr. Snow's recommendation?

BOARD OF GUARDIANS

In England, the parish is the fundamental tier of local government. Saint James's parish encompassed the region serviced by the Broad Street pump. The Board of Guardians was elected by local citizens who owned property. The voters were usually small tradesmen or shopkeepers. The Board of Guardians was responsible, among other concerns, for maintaining public health, but relied on the advice of medical practitioners such as Dr. Snow.

MORE DETAILS ON THE BOARD

The Broad Street pump was located in St. James's Parish. The parish is governed by both the Vestry and the Board of Guardians. Membership in the Vestry was chosen by a variety of criteria but typically included the vicar and church wardens as ex officio members. The Board of Guardians was created by the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 as another local administrative body to address problems of the poor. The Board was elected by local citizens who owned property and paid taxes. The voters were usually small tradesmen or shopkeepers who were concerned with public safety and order. The Board of Guardians was responsible, among other concerns, for maintaining public health, but relied on the advice of local medical practitioners. Regarding taxation, the Board of Guardians suggested the rate that should be paid in the parish to assist the poor while the Vestry would vote to either accept or reject the Board's suggestion. Hence the ultimate financial authority was with the Vestry.

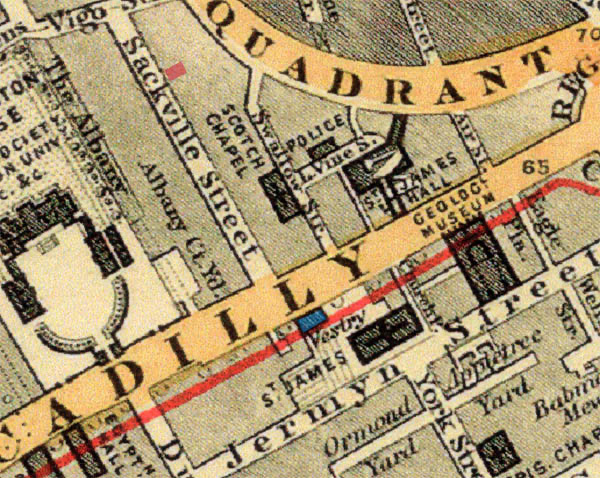

As shown in Stanford's 1862 map, the Vestry Hall (in blue) of St. James Church is where the Board of Guardians met with John Snow on September 7, 1854, following Snow's walk from his nearby Sackville street home (in red).

In St. James's Parish, the Board of Guardians and the Vestry regularly met at the Vestry Hall west of the St. James's Church, as did the Westminster Medical Society.

There were several views of what happened on September 7, 1854 when Dr. John Snow spoke to the Board of Guardians at the Vestry Hall and the impact thereafter on the Broad Street outbreak.

VIEW OF A GOOD FRIEND

Snow's good friend, Dr. Benjamin Richardson, wrote years later in 1858 of the September 7th meeting: "When the Vestry men were in solemn deliberation they were called to consider a new suggestion. A stranger had asked in a modest speech for a brief hearing. Dr. Snow, the stranger, was admitted, and in a few words explained his view of the 'head and front of the offending'. He had fixed his attention on the Broad Street pump as the source and center of the calamity. He advised the removal of the pump handle as the grand prescription. The Vestry was incredulous but had the good sense to carry out the advice. The pump handle was removed and the plague was stayed. There arose, hereupon, much discussion among the learned... but it matters little for the plague was stayed."

VIEW OF A LOCAL PHYSICIAN

In 1866, twelve years after the event, Dr. Edwin Lankester wrote further of the pump handle incident. He was a member of a local group that looked into the causes of the Broad Street outbreak, and was later to become the first medical officer of health for the St. James's district (the area where the outbreak occurred).

"The Board of Guardians met to consult as to what ought to be done. Of that meeting, the late Dr. Snow demanded an audience. He was admitted and gave it as his opinion that the pump in Broad Street, and that pump alone, was the cause of all the pestilence. He was not believed -- not a member of his own profession, not an individual in the parish believed that Snow was right. But the pump was closed nevertheless and the plague was stayed."

VIEW OF A LOCAL CLERGYMAN

At the time of the Broad Street pump outbreak, Reverend Henry Whitehead was a 29 year old cleric at a church in the Broad Street area. He became interested in the epidemic and conducted his own investigation, independent of Dr. Snow, although both served on the Cholera Inquiry Committee formed by the Vestry of St. James Parish, to address the outbreak. In reflecting later on Snow, Rev. Whitehead wrote: "One member of the committee, the late Dr. Snow, even before the committee was formed, had propounded that the cholera outbreak was in some manner attributable to the use of impure water of the well in Broad Street, and indeed had prevailed upon the parish authorities to remove the handle of the pump on the 8th of September." He went on to opine, "But scarcely anyone seriously belied in his theory."

Expanding his thinking at the time, Whitehead wrote: For my own part, when I first heard of it, I stated to a medical friend my belief that a careful investigation would refute it." But then he proclaimed his own involvement: "I added that I knew the inhabitants of Broad Street so well, and had occasion almost daily to spend so much time among them, that I should have no great difficulty in making the necessary inquiries. Accordingly I began an inquiry which ultimately became very elaborate." His inquiry during the spring of 1855 consisted of interviewing residents of Broad Street and going through the Weekly Returns of Death in London published by the office of the Registrar-General, all at the behest of the Cholera Inquiry Committee. And so, an unusual but productive partnership developed between a skeptic and a hypothesis-tester, bringing truth to the fore.

Curate Whitehead's first Observations of the Outbreak

On previous occasions the cholera had visited St. Luke's but lightly, destroying no more than ten of its inhabitants in 1849 and about the same number in 1832. There was every reason, according to human calculations, to anticipate a similar immunity from its ravages during the present season. The people had watched with interest the elaborate construction of a new sewer, which, when finished, was deemed amply to atone for its recent interruption of business by the supposed freedom from pestilence which it secured.

The bills of mortality during the month of August,1854 encouraged this belief, announcing a total of only four deaths from cholera in four weeks. It is true that three of those deaths were of a startling nature. One morning [on] 16 August a tradesman in Berwick Street, much respected by his neigbours, took down his shutters to be replaced in the evening long before the usual hour as the signal of his decease. The same day, in the same street, the wife of a respectable mechanic expired after a short illness. Her husband survived only long enough to express his desire that he should be buried at the same time with her. A crowd assembled to witness the departure of the hearse with its double burden…. As no more deaths immediately followed, [however] all apprehension was presently allayed.... It was rather prematurely concluded that the cholera had already come, done its worst and retired.

The morning of Friday, 1 September, 1854, was destined to dispel any such delusion The first intimation which the writer received of the sad incidents of the night came in the form of a summons to the deathbed of one with whom he had cheerfully conversed at a late hour on the preceding evening. A patient, gentle widow, she was an object of special interest to all who knew her. Many a pitying glance was cast that morning upon her little children as they moved about, [scarcely] conscious of what was happening…. A fearful tragedy was enacting in that one small house, when eight of its twenty inmates died in quick succession before the night of 4 September....

Elsewhere scenes as melancholy presented themselves in startling abundance. The tale that has just been told of one house is but given as a description of what was passing in many. In the very next that the writer entered, there lay at the point of death four persons who the evening before had retired to rest in health and strength.

The epidemic burst out at midnight on the morning of 1 September, 1854. The deaths on that day (Friday) followed each other with frightful rapidity. On Saturday they seemed to be, and were, more numerous still. Moreover, the inhabitants were more fully alive to the dread reality of what was taking place. For many reasons, this day was the most tragic of all in appearance:

...The wild rush and eager inquiry for the nearest medical assistance,

— the astonishment of the stranger passing casually through the district,

— the varied demeanour of the resident population,

— the streets white with chloride of lime,

— the dead cart and its followers,

— the midnight crowd unwilling to retire to rest....

—On Sunday, 3 September, 1854, many persons strove hard to persuade themselves that it was abating its violence but reluctantly abandoned the notion before evening. There seemed to be more uncertainty as to its ravages. [There was] no longer the incessant putting up of shutters to serve as an index. A feeling of mysterious solemnity pervaded the crowd at the thought of what might be passing behind those dosed shutters, whilst the dismal spectacle of hearses, by this time in constant requisition, added a new and gloomy feature to the scene.

Monday came [with] no apparent cause for hope. The deaths seemed, and were, as numerous as ever. All the strange scenes of the preceding days were renewed.

But at length on Tuesday morning, the medical men, the clergy, missionaries, etc., who alone were able to take a comprehensive view of the rate of mortality, began to perceive a ray of sunshine piercing the dark clouds. Right glad were they to have it in their power, for the first time since Friday, to reassure the anxious multitudes who thronged about them and bid them wait patiently. For the Lord God was withdrawing the scourge from among them. And verily, if ever there was a season when men felt that they were in the hands of the Lord, it was then when all human aid appeared of no avail. Medical skill seemed to be baffled and set at nought by the deadly foe which it had to encounter. Happily, it was no delusive hope which on the morning of [Tuesday], 5 September,1 1854, was held out to the eager inquiries of the inhabitants. For the deaths on that day fell nearly 50 percent. The doctors, one and all, declared that the disease had become much more manageable. The mortality then gradually decreased.

Many persons accosted the writer in the streets on Wednesday and Thursday to ask if there were any necessity for them to remove out of the district. [They] followed his advice when he told them to stay where they were. And yet,for want of some public and easily accessible information as to the precise state of the case, the inhabitants, though by no means panic-struck, were now decamping in such numbers that it was possible to find whole houses completely deserted....

The Index Case?

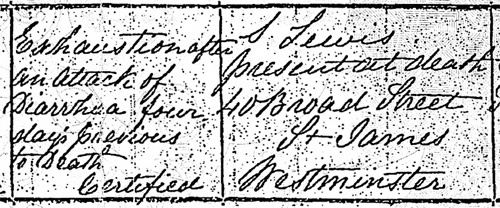

In his record searches Whitehead came across an entry that listed the death on September 2, 1854 of a five month old daughter residing with her family at 40 Broad Street. It did not list cholera as the cause of death, but rather stated she died due to “exhaustion after an attack of Diarrhea four days previous to death.” This finding and the contents of an earlier interview, Rev. Whitehead may have discovered the origin of the Broad Street pump outbreak, which started on August 30, 1854. The infant girl at 40 Broad Street (immediately next to the pump) had an attack of diarrhea on August 28th that lead to her death on September 2nd.

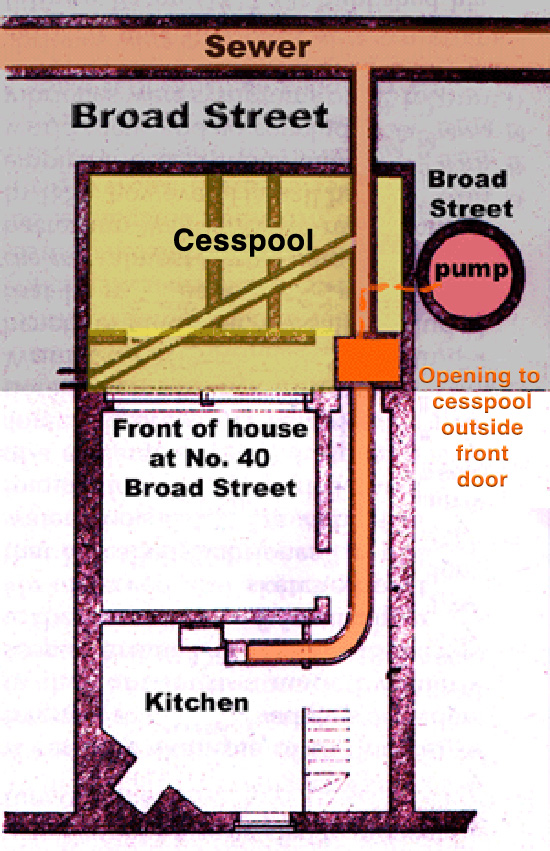

The mother described to Rev. Whitehead how, during her baby's illness, she had steeped her soiled napkins in pails of water and had emptied some of these into the cistern at the front of the house. Whitehead was struck by the dangerous proximity of the cistern to the pump well and convinced a government engineer to examine the area.

This examination revealed the seepage of fecal matter through the decayed brickwork of the cistern to the well which was less than three feet away. If the child had died of cholera (which Whitehead supposed), then this probably would have been the index case that started the Broad Street pump outbreak.

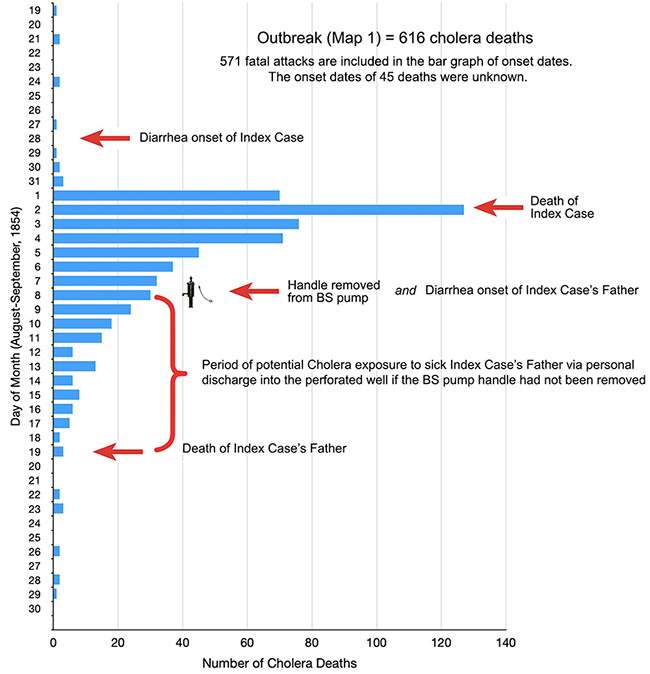

Reverend Whitehead's views on the effects of the Board of Guardians removing the pump handle were presented in 1867, thirteen years after the outbreak had occurred: "It is commonly supposed and sometimes asserted even at meetings of Medical Societies that the Broad Street outbreak of cholera in 1854 was arrested in mid-career by the closing of the pump in that street. That this is a mistake is sufficiently shown by the following table which, though incomplete, proves that the outbreak had already reached its climax, and had been steadily on the decline for several days before the pump-handle was removed."

The table he presented is not exactly the same as Snow's Table 1 [See Stream 2: a.] but showed at the time that the number of fatal cholera attacks had diminished from 142 on September 1st [actually 143] to14 on September 8th [actually 12] , the day on which the pump was closed. Thereafter the new fatal cholera cases fell to single figures and slowly dwindled away [Note: bar graph created by Frerichs uses the data in Snow's Table 1].

Whitehead went on in his presentation: "I must not omit to mention that if the removal of the pump-handle had nothing to do with checking the outbreak which had already run its course, it had probably everything to do with preventing a new outbreak, for the father of the infant, who slept in the same kitchen, was attacked with cholera on the very day (September 8th) on which the pump-handle was removed. There can be no doubt that his discharges found their way into the cistern and thence to the well. But, thanks to Dr. Snow, the handle was then gone."

SNOW'S THOUGHTS ON CHOLERA

A month after the September 8th removal of the pump handle, Dr. Snow spoke of his views on cholera before the Medical Society of London on October 14, 1854. An account of his talk appeared in the October 21st issue of the Lancet.

MEDICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON

Mr. Headland, President.

Saturday, October 14th, 1854

Dr. Snow considered that the cholera poison acted upon the alimentary canal, and not on the blood or nervous system. In every case which he had seen, the evacuations had been sufficient to account for a collapse, without reference to any other cause. There was no poison in the blood in a case of cholera; in the consecutive fever, as it was called, the blood became poisoned from urea getting into the circulation in consequence of the kidneys not acting, but not from any poison having been present from the beginning.

There was nothing in the atmosphere to account for the spread of cholera, which he believed was spread from person to person; and that in all cases it could be traced in this manner. If atmospheric, why did it attack one or two persons only in a locality, and these have direct communications with each other?

Such cases he had seen at Sydenham, where there had been only two instances of the disease. The first case in the outbreak of 1849 had occurred to a sailor in Bermondsey; the second affected person was the successor to the sailor in the room in which he died. He thought he had collected evidence enough to show that in all cases cholera was propagated by swallowing some portion of the evacuation of an affected person. These as was well known, flowed into the bed, etc., and persons attending on the sick might easily take the poison unaware.

With respect to the class of persons affected by the disease, he believed the very poor and vagabonds suffered less, in proportion, than descent, respectable persons. He regarded the cholera and diarrhea, as lately prevalent, to be the same disease in different degrees of intensity. We observed the same difference in scarlatina [scarlet fever, caused by the bacteria Streptococcus pyogenes, not yet known] and other diseases.

__________________________________

Was his action important, based on sound logic and understanding of the local situation? Or did John Snow and the Board of Guardians over-react?

Contemporary epidemiologists view removing the pump handle as appropriate, and honor Snow's action to safeguard the public, even in the face of biologic and epidemiologic uncertainty.

INDEX CASE AT 40 BROAD STREET

Did the index (or first) case of the Broad Street Pump outbreak live at 40 Broad Street, close to the pump? Reverend Henry Whitehead thought so after his detailed investigation of cholera cases in 1854-55 following the outbreak.

The woman living at 40 Broad Street in the back parlor (Sarah Lewis, wife of police constable Thomas Lewis) lost both her five-month old child, Frances, and husband to cholera. In the four to five day interval between her child's onset of diarrhea on August 28-29, 1854 and subsequent death on September 2nd , Mrs. Lewis had soaked the diarrhea-soiled diapers in pails of water in her kitchen. Thereafter she emptied the pails of water into the kitchen sink piped to the cesspool in front of the house or directly into the cesspool opening by the front door of her house.

CESSPOOLS

Cesspools in London, like those in the Broad Street area, were emptied at periodic intervals by "night-soil men," often coming in evenings when the stench would lessen. They would dig out the feces and urine in the cesspools with shovels and baskets, then disposed the material in horse- or mule-pulled tank wagons. These tanks would then be taken to the countryside and either emptied on a paddock or in a "night-soil depository," or mixed in with other organic waste such as food scraps or horse manure for drying. Once dried, the waste would be placed in bags and sold to farmers as crop fertilizer. Since the germ theory was not yet understood or accepted, there was no thought of further microbial contamination.

Likely baby Lewis had Vibrio cholerae (not yet known) which contaminated the diaper used to absorb diarrhea. Reverend Whitehead conveyed his suspicion concerning the possible index case to the Medical Committee of the Board of Guardians responsible for the public health of the area.

The Board sent a surveyor to assess the situation. Over a several months span, he ordered an excavation of the front section of the house, the adjacent street and the Broad Street pump, folowed by a report issued May 1, 1855. The surveyor included a diagram of the home and cesspool (see stylized image) and reported that decayed brickwork in the cesspool resulted in seepage of fecal debris from the infant's diapers to the Broad Street pump which was 2 feet 8 inches away. As the surveyor wrote, "...the condition of the cesspool, the defective state of its brickwork and also that of the drain, no doubt remains upon my mind that constant percolation for a considerable period had been conveying fluid matter from the drains into the [Broad Street pump] well."

The September 1854 death certificate for baby Frances was filled out by Dr. William Rogers, a local physician who maintained a practice a few blocks away. Dr. Rodgers opined in a detailed letter to Reverend Whitehead that the cause of death of Frances Lewis was acute diarrhea, not cholera, an opinion that he repeated at a meeting of the London Epidemiological Society. Since Vibrio cholerae was not discovered until 1884, it is doubtful that Dr. Rogers could have accurately distinguished by signs and symptoms alone the difference between non-cholera acute diarrhea and cholera diarrhea. Thus Whitehead's theory is certainly plausible that the infant at 40 Broad Street was the index case.

Source: John Snow and the 1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak, Harvard Online, 2016.

Thomas Lewis, the baby's father, came down with a fatal attack of cholera on September 8, 1854, the same day that the Board of Guardians had the Broad Street pump handle removed. Perhaps he became infected directly from his daughter Frances who died on September 2nd, experiencing an incubation period of 6-7 days, on the long side. According to a systematic review in 2012 by Azman et al, such an incubation period occurs in no more than 2-3 percent of all cases.

Alternatively, Thomas Lewis may have become infected when dislogging household waste through the opening at the front door of the contaminated cesspool. Finally, he might have consumed cholera-contaminated water from the Broad Street pump situated close to his front door. What is important from a public health point of view is that once Thomas Lewis became infected, the cesspool to Broad Street pump link due to cracks in the casing would have remained a plausible source of community infection until Lewis's death on September 19, 1845, altered by the September 8th removal of the pump handle.

Given the diarrhea symptoms of the young infant and the surveyor's assessment of the cesspool, Reverend Whitehead likely determined the index case that started the infamous Broad Street pump outbreak.

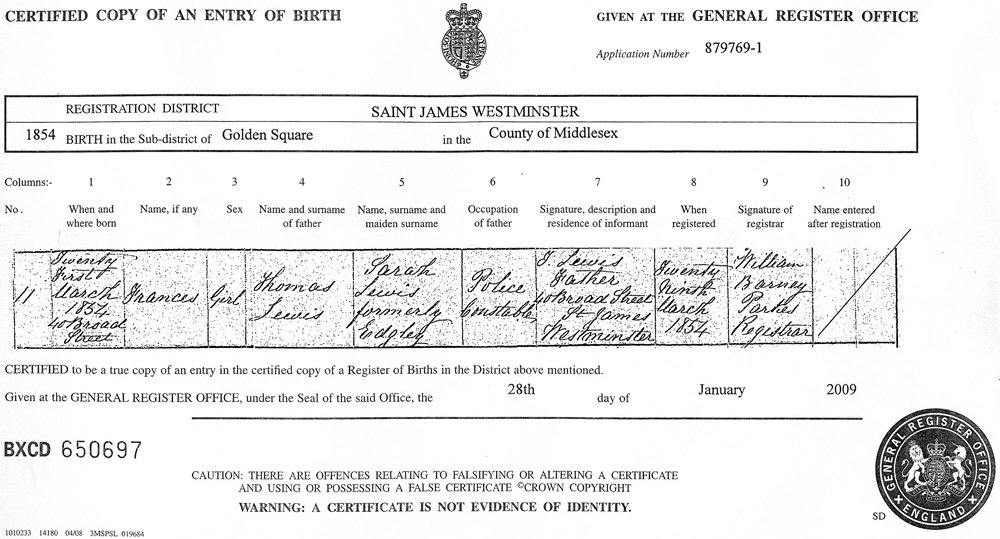

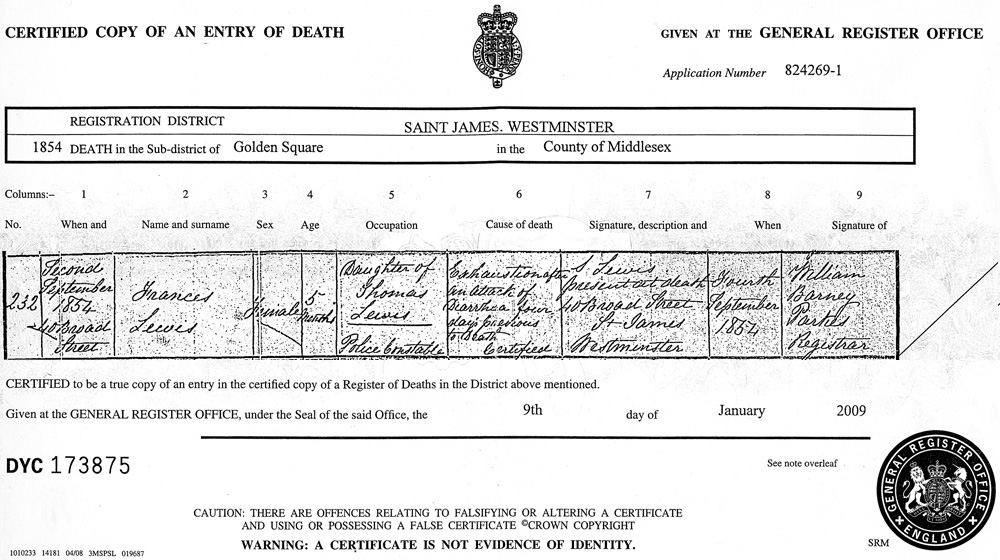

BIRTH AND DEATH CERTIFICATES OF INDEX CASE AND DEATH CERTIFICATE OF HER FATHER

Below is a copy of the birth certificate of Frances Lewis, believed to be the first (or index) case of the Broad Street Pump outbreak. Frances was born in March 1854 to Police Constable Thomas Lewis and his wife Sarah Lewis. Nearly five months later on Monday morning, August 24th, Frances developed the intense diarrhea which would subsequently cause her death, and thereafter lead to deaths among many others in her community.

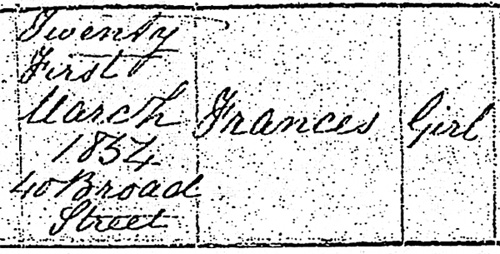

BIRTH OF FRANCES LEWIS

Seen more clearly to the right, Frances was born on March 21, 1854 in a home at 40 Broad Street, directly adjacent to the Broad Street pump.

After baby Frances develped diarrhea on August 24th, her mother Sarah soaked the dirty diapers in a bucket of cold water. Before actually washing the diapers, she poured the dirty water into the cesspool (a tank where sewage is held) in the front area under the house and street. Crevices and breaks in the cesspool wall resulted in leaks into the adjacent Broad Street pump well.

During the same time, Dr. John Snow was unaware of baby Frances and the plight of the Lewis family. Instead, he was busy studying another epidemic of cholera, later termed the "Grand Experiment," in communities to the South of the River Thames. The Lewis family was tended by Dr. William Rogers, their local physician. Dr. Rogers did not suspect that baby Frances had cholera. Her condition worsened in the coming days and by Wednesday, she appeared listless and exhausted, but showed no signs of fever or cramps, and did not seem blue or cold. On Saturday, September 2nd, baby Frances died. Dr. Rogers filled out her death certificate, as shown below.

DEATH OF FRANCES LEWIS

In the death certificate, seen to the right, Dr. Rogers noted that baby Frances died of "exhaustion, after an attack of diarrhea four days previous to death." He also noted that mother Sarah Lewis was present at the death, which occurred at 40 Broad Street. Dr. Rogers did not believe that the death was due to cholera.

Ten months following the death, Dr. Rogers attended a meeting of the Epidemiological Society of London where Dr. John Snow was presenting a talk on the Broad Street Pump outbreak. Included in the talk, was the investigative work of Reverend Henry Whitehead which pointed the causative finger at baby Frances. Dr. Rogers objected, feeling that the evidence was insufficient that baby Frances had cholera and that even if she had, cholera could not have been transmitted from the Lewis home at 40 Broad Street to the Broad Street pump well. It is not clear if Dr. Rogers ever changed his mind.

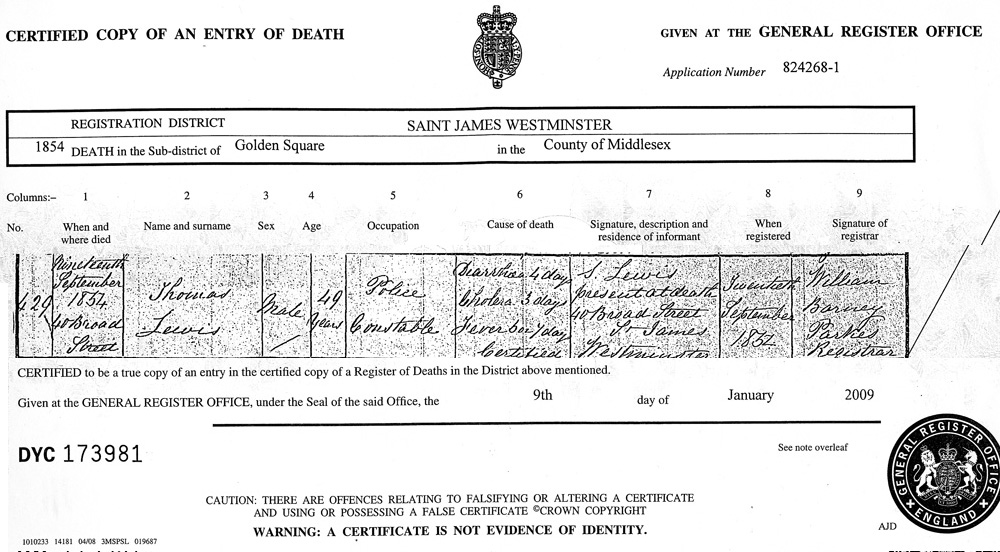

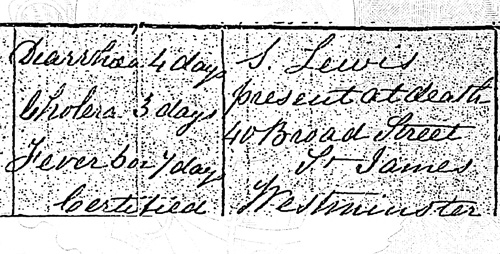

Cholera continued to visit the Lewis household, but this time it was father Thomas Lewis who had the disease. Six days after the death of his daughter, Police Constable Lewis on September 8th developed the symptoms of cholera. Like his daughter, he had rested in the front kitchen of 40 Broad Street. Being at the front of the house, it was easier for wife Sarah to pour the water from the rinsed diapers and fecal-ridden bedding into the front cesspool, which continued to contaminate the Broad Street pump well, rather than the privey in the back yard of the house. On the same day, the Board of Guardians, at the urging of Dr. John Snow, had the pump handle removed from the Broad Street pump. As the days went by, Thomas Lewis remained sick and his wife Sarah continued to empty pails of water, used to soak his soiled bedclothes, into the front cesspool. After eleven days of illness, Thomas Lewis died of cholera on September 19, 1854. If the handle of the Broad Street pump had not been removed on September 8th, it is likely that the contamination of the pump well via the cesspool would have continued until September 19th when Thomas Lewis died.

DEATH OF THOMAS LEWIS

As seen at the right, Police Constable Lewis had fever for seven days, diarrhea for four days and diagnosed cholera for three days. His wife Sarah Lewis was present at his death, as she was at the death of baby Frances. On Tuesday, September 19, 1854 she became a widow with two children, 16-year old Thomas and 11-year old Anne. Her deceased baby daughter Frances was the likely index case for the Broad Street Pump outbreak.

REVEREND HENRY WHITEHEAD

Although he had no formal medical education, the epidemiology of cholera intrigued Reverend Whitehead. So who was this religious leader and how did he get interested in cholera?

Reverend Henry Whitehead (1825-96) was born on September 22, 1825 in the seaside town of Ramsgate in Kent by the Straits of Dover. His father was master at Chatham House, a small public school in the area. Henry was the eighth of ten children and grew up in the school, where later he became an assistant master. In 1847 at age 22, he left home and his potential teaching position to attend Lincoln College, University of Oxford. It was here that he made up his mind to enter the Anglican Church. After he obtained his B.A. in 1850, he left for London to seek ordination.

His first employment was as assistant curate (i.e., junior priest) with the Vicar of Saint Luke's Church, Berwick Street in Soho, London, near the home of Dr. John Snow and the future site of the Broad Street pump outbreak (see green site in map). Saint Luke's had been completely rebuilt in a decorated Gothic style in 1838-9 (see below, right) and was popular in the parish that included Broad Street and its environs.

Following his appointment to Saint Luke's Church and acquiring housing at #21 East Side, overlooking Soho Square, Whitehead in the coming years was soon elevated to Curate, with additional administrative duties. Yet with his social personality, he also maintained his activities among the residents of the crowded slums of the Berwick Street area and became a welcome visitor in the homes of his parishioners. His friendliness and social acceptance proved of great value to him in 1855 during the four months of his painstaking inquiry into the Broad Street pump outbreak, gathering vital information that would help John Snow.

FEAR AMONG PARISHIONERS

After deducing the source of the Broad Street pump outbreak, Dr. John Snow had convinced the Board of Guardians to have the handle removed from the pump. This they did on September 8, 1854. The epidemic continued to decline, but greatly disrupted the community. A newspaper correspondent for the Times described on September 15, 1854 what he had seen.

The outbreak of cholera in the vicinity of Golden Square is now subsiding, but the passenger through the streets which compass that district will see many evidences of the alarming severity of the attack. Men and women in mourning are to be found in great numbers, and the chief topic of conversation is the recent epidemic. The shop windows are filled with placards relating to the subject.

At every turn the instructions of the new Board of Health stare you in the face. In shop windows, on church and chapel doors, on dead walls, and at every available point appear parochial hand-bills directing the poor where to apply for gratuitous relief. An oil shop puts forth a large cask at its door, labeled in gigantic capitals "Chloride of Lime." The most remarkable evidence of all, however, and the most important, consists in the continual presence of lime in the roadways. The puddles are white and milky with it, the stones are smeared with it; great splashes of it lie about in the gutters, and the air is redolent with its strong and not very agreeable odor. The parish authorities have very wisely determined to wash all the streets of the tainted district with this powerful disinfectant; accordingly the purification takes place regularly every evening. The shopkeepers have dismal stories to tell — how they would hear in the evening that one of their neighbors whom they had been talking with in the morning had expired after a few hours of agony and torture. It has even been asserted that the number of corpses was so great that they were removed wholesale in dead-carts for want of sufficient hearses to convey them; but let us hope this is incorrect.

Whitehead was very troubled by the outbreak and its aftermath. He felt that many of the news reports were exaggerated and noted that even though the population of the area was decimated, there was "no panic which somewhat surprised [him] as [he] had always heard and read that great pestilences were invariably attended by wholesale demoralization of the population." Within a few weeks of the epidemic, Reverend Whitehead wrote his own account, entitled "The Cholera in Berwick Street (1854, see above)." No mention was made of the Broad Street pump. He was 29 at the time.

THREE INVESTIGATIONS

While Whitehead was issuing his initial publication, John Snow was busy gathering data to test his hypothesis that the spread of cholera was attributed to the Broad Street pump. At the same time, the Medical Committee of the General Board of Health was carrying out a local inquiry of its own. This third group seemed to favor the initial report of Whitehead, describing him as the "exemplary and indefatigable curate of St. Luke's." Snow's explanation of the outbreak was considered by the Medical Committee, but was rejected outright.

The debate among Committee members continued, and eventually they decided to expand the inquiry by circulating a questionnaire to people in the area. The modest returns did not fulfill their expectation. The Committee then decided to seek information by personal interviews, but to this end needed more members. Among the eight new-comers were Dr. John Snow (then age 41) and Henry Whitehead. Thus with this one act, the three investigations into the cause of the cholera outbreak merged into one. Likely it was at such a Medical Committee meeting that Snow and Whitehead met for the first time. In January 1855, Snow completed his book On the Mode of Communication of Cholera. Shortly thereafter he gave a copy to the younger Reverend Whitehead.

THE DISBELIEVER

Having read Snow's 1855 book, Whitehead remained unconvinced and wrote Snow of his critical thinking. He felt that an intensive inquiry would reveal the falsity of the Snow's hypothesis regarding the Broad Street pump. Having so forcefully expressed his opinion, Whitehead was determined to carryout such an inquiry. In the first half of 1855, he visited many people in the area, sometimes four or five times to confirm the facts he needed. For every person who had died of cholera, he ascertained the:

1) name,

2) age,

3) position of the rooms occupied,

4) sanitary arrangements,

5) consumed water with respect to the Broad Street pump, and

6) the hour of onset of the fatal attack.

At the end of his inquiry, Whitehead wrote in a June 1855 report Special Investigation of Broad Street, "Slowly and I may add reluctantly," the conclusion was reached "that the use of water [from the Broad Street pump] was connected with the continuation of the outburst."

The Medical Committee reviewed Snow's book and Whitehead's most recent report. While they did not accept Snow's hypothesis regarding the cause of cholera (many believed in the miasma theory), the Committee reached the conclusion on August 9, 1855 that "the sudden severe and concentrated outbreak beginning on August 31st [1854] and lasting for the few early days in September was in some manner attributable to the use of the impure water of the well in Broad Street." The vote for and against this benign conclusion was split equally, requiring the Chairman of the Committee to cast the deciding affirmative vote.

MOVING ON

Whitehead remained at St. Lukes until 1857, when he left to seek another curacy. In the ensuing years he served several London parishes and in addition to cholera, developed special interest and expertise in juvenile delinquency.

In 1865 when cholera again came to London, Whitehead turned his attention back to the disease. Dr. John Snow had died seven years earlier, leaving Whitehead as the main authority on the earlier Broad Street outbreak. Because of rising public alarm. Whitehead again published his observations, cautioning in December 1865 that public health lessons of the past should not be neglected. But to no avail. In the following year, cholera broke out in the crowded slums of East London and spread by contaminated water to thousands of homes. The Bishop of London called for volunteers from among the clergy who had previous experience with cholera, and Reverend Whitehead was among those who responded.

Following the East London epidemic, Whitehead took up a curacy in Stepney. His two years there were followed by a short service in Hammersmith, after which he returned to the dock area as Vicar of St. John's Church in Limehouse. Another three years went by and he was offered a position in Brampton, a small town in Cumberland, supported by the Earl of Carlisle. He accepted, leaving behind a legacy as vicar in several districts of London. Before leaving london , his many friends and colleagues gave him a farewell dinner on January 16, 1874 at the Rainbow Tavern in Fleet Street (see below).

THE BELIEVER

In what many felt was the longest after-dinner speech on record, Whitehead at the Rainbow Tavern offered the following personal reminiscence of Dr. John Snow.

Yet for wholly exceptional reasons, I may say a few words about Dr. John Snow — as great a benefactor in my opinion to the human race as has appeared in the present century. Dr. Snow had long believed that he had discovered the mode in which cholera is propagated and fortunately he was at hand to direct an inquiry into the cause of the Broad Street outbreak, which inquiry resulted in a remarkable confirmation of his hypothesis.