Stream 3 - The "Grand Experiment"

a: Introduction and Part 3 of Snow's 1855 Book, Map 2

OVERVIEW

Introduction to Snow's Re-issued Book by Wade Hampton Frost, M.D. (1880-1938)

Prominent epidemiologist Wade Hampton Frost, MD in 1936 was asked to write an introduction to a re-issuance of John Snow's book, the second edition of On the Mode of Communication of Cholera along with two other articles. At the time, Frost was a professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health. He had been Chair of the Department of Epidemiology from 1919 until 1938 and Dean of the School from 1931 until 1934. As a long-time admirer of John Snow, Frost had created educational material on Snow for his students, shared later with faculty and students at other public health schools.

Medical colleague Thomas M. Daniel, M.D. wrote in his 2004 book of Frost's professional achievements: "Frost was the first to understand the importance of transmission in poliomyelitis — knowledge that prepared the ground for the worldwide campaign against that disease; the first to understand the cyclical nature of influenza; the first to develop the historical cohort approach and undertake longitudinal cohort analyses; and the first to design life tables for expressing data in person-years."

Source: Daniel, T.M. Wade Hampton Frost, Pioneer Epidemiologist 1880-1938: Up to the Mountain, University of Rochester Press. illustrated edition (October 1, 2004).

Text in bold are Frost's views of John Snow as an epidemiologist and his classic study, "the Grand Experiment," involving the Lambeth (unexposed) and the Southwark and Vauxhall (exposed) water companies.

Photo in 1921, age 41

Source: Frost, Wade Hampton. Introduction, On the Mode of Communicaton of Cholera, second edition (reissued), Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1936.

Epidemiology at any given time is something more than the total of its established facts. It includes their orderly arrangement into chains of inference which extend more or less beyond the bounds of direct observation. Such of these chains as are well and truly laid guide investigation to the facts of the future; those that are ill made fetter progress. But it is not easy, when divergent theories are presented, to distinguish immediately between those which are sound and those which are merely plausible. Therefore it is instructive to turn back to arguments which have been tested by the subsequent course of events; to cultivate discrimination by the study of those which the advance of definite knowledge has confirmed.

A nearly perfect model is John Snow's analysis of the epidemiology of cholera which led him to the confident conclusion that the specific cause of the disease was a parasitic micro-organism, conforming in all essentials of its natural history to what is now known of the Vibrio cholerae. His central conclusion lies now within the boundaries of direct observation; it is reached by a shorter and easier path than that which he was obliged to follow. But his argument has the permanence of a masterpiece in the ordering and analysis of a kind of evidence which enters at some stage and in some degree into every problem in epidemiology.

Looking back to the time when Snow wrote, we are apt to be more impressed with the deficiency of his knowledge, lacking all that the technique of modern bacteriology has since supplied, than with the extent and significance of the positive facts at his command. With some exceptions, the communicable diseases of man and the domestic animals which are of common occurrence in Europe had been differentiated clinically; their gross and microscopic pathology was fairly well established; their characteristic distributions in nature were known, and it had been demonstrated for not a few of them that they could be artificially transmitted by inoculation of "morbid matter" in minute quantity. But for certain diseases, including the enteric infections, this demonstration was lacking, and the indirect evidence of communicability was by no means so plain as to be incontestable.

Ideas as to the nature of the materies morbi were converging toward present-day conceptions, but were not at all clearly focused. The analogy between infection and fermentation, which Fracastorius had perceived three hundred years earlier, was generally recognized; and moreover it was known that the processes of fermentation and putrefaction were constantly associated with the presence of living organisms of microscopic size, though whether or not these were spontaneously generated was still a matter of controversy. The active agent in conveyance of infection was generally pictured as being related in some way to the lower orders of known microorganisms, but not usually as being itself a living organism, still less commonly as being an obligate parasite, bound by the law of biogenesis as now accepted. A general theory of infection closely approximating modern views had, indeed, been clearly formulated by Henle [Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle], in 1840, but it had not been widely accepted. The more common view related infectious diseases to micro-organisms much more loosely; and in England, the ideas embodied in the so-called "pythogenic" theory were much in favor.

In this state of uncertainty as to the nature of the more common diseases, cholera presented a riddle peculiarly difficult to solve by the indirect method of inference from its mode of occurrence. The difficulty was not lack of detailed information. The epidemics which swept across Europe in the middle third of the century were matters of tremendous concern and were diligently studied by offcial commissions and individuals. In England, where epidemics prevailed in 1831-32, 1848-49, and 1853-54, the studies were of notable excellence. The genius and industry of William Farr produced comprehensive reports of the epidemics of 1848-49 and 1853-54, and supplied current information while they were in progress; admirable factual reports were made by the General Board of Health and the Royal College of Physicians; and the literature of the day contained innumerable detailed accounts of the local dissemination of the disease. But the facts themselves were most confusing. Instances of local spread with every appearance of direct communication from person to person were offset by equally striking instances of failure to spread to those in close contact with the sick, and of the disease developing without traceable relation to prior cases. Moreover, the variations in the local prevalence of cholera appeared to be capricious in the extreme. If it seemed to be the rule that it prevailed most severely in lowlying places, and in a notably filthy environment, the exceptions to these and similar laws were too numerous to be disregarded.

The theories evolved to explain these complex facts were numerous and diverse, but so far as any one idea was dominant it was probably that expressed by Sutherland as follows:

It appears as if some organic matter, which constitutes the essence of the epidemic, when brought in contact with other organic matter proceeding from living bodies, or from decomposition, has the power of so changing the condition of the latter as to impress it with poisonous qualities of a peculiar kind similar to its own.[1]

To this was added the conception of "localizing influences" promoting the propagation of the poison, and "predisposing causes," increasing susceptibility to its effects. There were many differences of opinion as to whether the "cholera poison" might be spontaneously generated in different countries, or must be introduced from pre-existing foci; whether it was spread solely by diffusion through the atmosphere or attached itself to solid bodies; whether or not it was communicated by an effuvium (contagion) given off by the sick.

It is easier, at this distance, to see the defects in the current theories than to do them justice. Some were so vague and general as to be manifestly worthless, fitting one set of facts as well as another; others simply ignored some of the plain facts, as for instance when the General Board of Health resolutely closed its eyes to all evidence of communication from person to person or by commerce. But there were at least a few theories, such as Farr's, emphasizing the importance of elevation and drainage, which were well reasoned in accordance with an impressive array of facts. It is perhaps significant that they were directed so largely toward explanation of those phenomena of cholera which are still least explicable: its sudden extensions around the world, the vagaries of its geographic distribution, and its relation to climate, season, and weather.

How Snow perceived the thread of consistency which connected a seemingly chaotic mass of facts and followed it through to the conclusion that bacteriology has since confirmed, he himself tells plainly and simply, with the fresh enthusiasm of discovery, the restraint of a scientist. His account should be read once as a story of exploration, many times as a lesson in epidemiology.

In order to present the whole of Snow's argument, this volume reproduces in their entirety two of his works, his treatise On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, as published in 1855, and his address On Continuous Molecular Changes, More Particularly in Their Relation to Epidemic Diseases, delivered in 1853. The first of these is, by itself, a full and sufficient exposition of Snow's theory, evidence, and methods as applied to the specific problem of cholera. The second is important as connecting his views on cholera with his broad conception of epidemic diseases in general and relating these, in turn, to other natural phenomena. Together, these two dissertations show, one in broad outline, the other in detail, the pattern of his thought in epidemiology; his other papers in this field are not without interest, but they all fit into this general pattern, and their reproduction is not essential to the main purpose which this volume is intended to serve. Two of them, however, need to be mentioned, a prelude and a postscript, respectively, to his major work on cholera.

The treatise On the Mode of Communication of Cholera which is reprinted here is a second edition, "much enlarged," of a pamphlet published in the summer of 1849. This was followed immediately by a somewhat more extended paper published under the title "On the Pathology and Mode of Communication of Cholera" in the Medical Times and Gazette of November 2 and November 30, 1849. The essential difference between these two earlier papers and the expanded edition of 1855 is that the latter contains much new factual evidence, chiefly the analyses of mortality as related to the several water supplies of London in 1832 and 1849 and, of course, all the observations made in 1854. It has seemed unnecessary to reproduce the first paper in this volume, since it is included, for the most part in identical or slightly revised language, in the second edition; but it is important to remember that when Snow undertook his personal investigations in the epidemic of 1854 he already had in mind a definite and well matured theory which he was eager to put to the rigid test which the intermingling of two water supplies made possible.

The postscript to Snow's work of 1855 is his paper on Cholera and the Water Supply in the South Districts of London, published in October, 1856, when detailed statistics of the population using the two principal water supplies in each subdivision of this area became available from the report of an official inquiry conducted by the General Board of Health. Of this a brief account is given in an appendix to this volume. It is not altogether essential to Snow's original argument, which was already well established, but confirms it in detail and shows his keenness in statistical analysis.

How far Snow's ideas were original is diffcult to determine. He read widely and drew upon the ideas as well as the facts of his day, and it is certain that the general conception of epidemic disease which he expressed was not altogether unfamiliar at the time. Henle, approaching the subject from a different angle, had already expressed broadly similar views as to the nature of infectious diseases and, though no direct allusion to his work has been found in Snow's writings, he must have known of it, at second hand if not in the original. Budd [Dr. William Budd (1811-1880), English physician, infectious disease epidemiologist and and follower of Snow's research] certainly shared Snow's views, but notwithstanding that he himself had arrived at similar conclusions concerning cholera as early as 1849, he generously accords Snow full credit for independent and more complete development of the theory. The belief that cholera was communicable from person to person through a specific poison was not unusual. Some part of Snow's conception that cholera was due to a specific micro-organism, an obligate parasite, propagating only in the human intestinal tract and disseminated by ingestion of excreta, was expressed by a number of contemporary writers; but seldom if ever was the whole idea expressed, and no one else followed it through to such full development. That Snow's contemporaries considered his theory of cholera to be original is evidenced by the fact that they referred to it as "Dr. Snow's theory" and, in their discussions, differentiated it from all the other theories which it was customary to mention.

The extent to which the ideas and evidence advanced by Snow were to be accepted in his lifetime is fore shadowed in this passage from his own first paper on cholera (1849): "Many medical men to whom the above circumstances respecting the water have been mentioned, admit the influence of the water, without admitting the special effect of the new element introduced into it - viz., the cholera evacuations, in communicating the disease.They look upon the bad water as only a predisposing cause, making the disease more prevalent amongst those who use it -- a view which, in a hygienic sense, is calculated to be to some extent as useful as the admission of what I believe to be real truth, but which, I think, will be found to be untenable, when the circumstances are closely examined."

After Snow's evidence convicting the water supply of the Southwark and Vauxhall Company had been published, none but the most stubborn could deny the influence of contaminated water. And when the facts had been confirmed by the official inquiry which was completed in 1856, the case was not open to further argument. But what was accepted was merely the fact that impure water had, in some way, the effect of increasing the risk of cholera, and this had long been admitted by many. Snow's explanation of the fact was by no means accepted. Simon's [Dr. John Simon, Medical Officer of Health for the City of London ] report on the official inquiry which confirmed Snow's facts took pains to make this clear, coming to the conclusion that "under the specific influence which determines an epidemic period, fecalized drinking-water and fecalized air equally [Snow did not accept the miasmatic theory of bad air, and hence differed over the three words "fecalized air equally" in Simon's report] may breed and convey the poison." [2]

Even Farr, who had immediately seen the significance of Snow's first observations, who had given whole-hearted aid in extending them, and who was destined himself to play the principal role in proving that the next epidemic of cholera in London (1866) was water-borne - even Farr gave only a qualified acceptance to Snow's explanation. Nearly twenty years later such an authority as Hirsch [Dr. August Hirsch,a German physician and public health official, authority on cholera andd supporter of the miasma theory] was still referring to contaminated water as a "predisposing cause" of cholera. Among English writers of distinction Budd seems to have stood nearly if not quite alone in prompt and unqualified acceptance of Snow's theory as well as his facts.

Any immediate influence which Snow's work may have had in promoting the improvement of public water supplies is obscured by the fact that extensive improvements in several of London's supplies, including that of the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, had already been ordered before the epidemic of 1853-54,to be effective within specified time limits. Nevertheless he did succeed in convincing his contemporaries that sewage pollution of drinking-water was a major rather than a minor factor in the conveyance of cholera. Thirty years later, when all controversy on this point had subsided, Sir John Simon, who, in Snow's lifetime, had stood aloof from him, classed his proof of this principle as "the most important truth yet acquired by medical science for the prevention of epidemics of cholera." [3]

Snow lived only four years after the epidemic of 1854, and in this time he had no opportunity to add to his observations of cholera, which had disappeared from Great Britain. He continued, however, to pursue studies extending to other diseases two principles which he had established for cholera: the tremendous importance of water as a vehicle of specific infection, and the harmlessness -- as regards infectious disease -- of the "effuvia" from dead organic matter, which were so generally considered at the time to breed pestilence. For both these doctrines, especially the latter, he was severely criticized, but avoiding heated controversy, he sought facts. In 1858, in a paper on Drainage ond Water Supply in Connexion with the Public Health (click here), one of the last published in his life-time, he deals with both subjects. Drawing upon the reports of the Registrar-General for his data, he first shows that among workers in the notoriously offensive trades, such as tanning and soap boiling, mortality rates are, in general, no higher than at corresponding ages in the whole group of industrially employed males. He then turns, by contrast, to the demonstrable relation between mortality and the sewage pollution of water. Presenting tables compiled from the Registrar-General's reports, he shows that prior to improvements in the water supply of the south districts of london, which were completed in the second quarter of 1855, the mortality rates from all causes, from typhus (mostly typhoid fever), and from diarrhoea in this area had consistently exceeded the rates in the districts north of the Thames. Dating from the change in water supply, this relationship was reversed, the rates of mortality being lower in the south districts than in the north. Here his work ended.

Of Snow's character, the circumstances of his life, the range of his interests, and the position which he held in his profession, an illuminating account is given in the memoir by Richardson, his warm friend and admirer [Dr. Benjamin Ward Richardson (1828-1896) was a physician, anaesthetist, physiologist, sanitarian, and extensive writer of medical history]. It gives the picture of a man singularly endowed with the ability to think in straight lines and the courage to follow his own thought. In medicine these abilities placed him in the front ranks of his day; in epidemiology they carried him a generation beyond it.

WADE HAMPTON FROST

Sources:

1. Sutherland, John, in Report of the General Board of Health on the epidemic cholera of 1848 and 1849, London, W. Clowes and Sons, 1854, Appendix (A), p. 8.

2. Report on the last two cholera epidemics of London as affected by the consumption of impure water; addressed to the Rt. Hon. the President of the General Board of Health by the Medical Officer of the Board.

3. Simon, Sir John, English sanitary institutions, London, Cassell and Co,, 189O, p.262.

Map Introduction to "Grand Experiment"

The 1856 map of England and Wales shows what took place in London during the 1854-55 cholera epidemic. Dr. John Snow was already busy with the Broad Street Pump outbreak in his home neighborhood, but the oportunity to expand his London epidemiologic horizon was too challenging to avoid. The redlined area below shows where his new challenge took place.

Two major developments enabled Snow's epidemiological quest. First, in 1841, the decade-interval population census in England and Wales began listing names of every individual. This was expanded in the 1851 census to include names, ages, sex, occupations and places of birth of each individual. Coupled with the equally detailed registraton of deaths, the 1851 census data enabled the derivation of mortality rates by age and sex, location and occupation.

Second, during the 1850s, two water companies that served similar London households with drinking water in an area south of the River Thames were strongly mandated by legislation to move their Thames River input valves to a region up-river where the water was more pure.

The tidal River Thames caused much of London's water polution problem since human waste that was disposed in the river was alternatively moved back and forth in the river, passing by the water companies input valves, but was never fully flushed out of the system. For a while, the river just smelled bad and the household water was unappetizing to consume. But then when cholera returned to the city in 1853-54, the River Thames became deadly. Dr. John Snow had theorized that cholera was due to a water-borne microscopic organism of some form or another (Vibrio cholerae had not yet been knowingly identified), now to be tested. Snow did not believe that cholera stemmed from bad smells or noxious air, referred to as "miasmas," the prevailinig theory of the day. To test his water hypothesis, he decided to take advantage of the slow up-river move of Southwark and Vauxhall company (red dot), leaving its customers for several years exposed to cholera.

At the same time, the Lambeth company (green dot) had successfully moved its inlet up river where the water was cleaner, not touched by the tides of the polluted River Thames, while the Southwark and Vauxhall Company delayed moving until two years later, opening an interval when one water company had moved and the other had not. As Snow noted, in an extensive part of London, there was complete intermixing of the water supply of the Southwark and Vauxhall Company with that of the Lambeth Company. Hence he had, what epidemiologists deemed to be a "natural experiment," not based on random allocation to the respective exposed and unexposed groups, but are very similar by circumstances. For testing his river water hypothesis using detailed mortality data, he felt that it was a "grand experiment," worthy of the name.

Source: Colton, GW. Colton's Atlas of the World, map of England and Wales,(created 1855), J.H. Colton and Company, New York, 1856.

ON THE MODE OF COMMUNICATION OF CHOLERA, PART 3

This second edition of John Snow's book, issued in 1855 three years before his death, is the historical treatise for which Snow is most famous in epidemiology. Included here is the third part of the book, pages 55-98, that addresses the "Grand Experiment." To peruse the 138 page book in its entirety, click on "JS Cholera Book" in the navbar at the top of each page.

Source: Snow, John. On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, 2nd Edition, London: John Churchill, New Burlington Street, England, 1855, pp. 55-98.

Contents of Part 3, pages 55-98

Outbreak of cholera at Deptford caused by polluted water

Communication of cholera by means of the water of rivers which receive the contents of sewers

Influence of the water supply on the epidemic of 1832, in London

Table II showing the mortality from cholera, and the water supply

Influence of the water supply on the epidemic of 1849, in London

Table III showing this influence

Communication of cholera by Thames water in the autumn of 1848

New water supply of the Lambeth Company

Effect of this new supply in the epidemic of autumn 1853

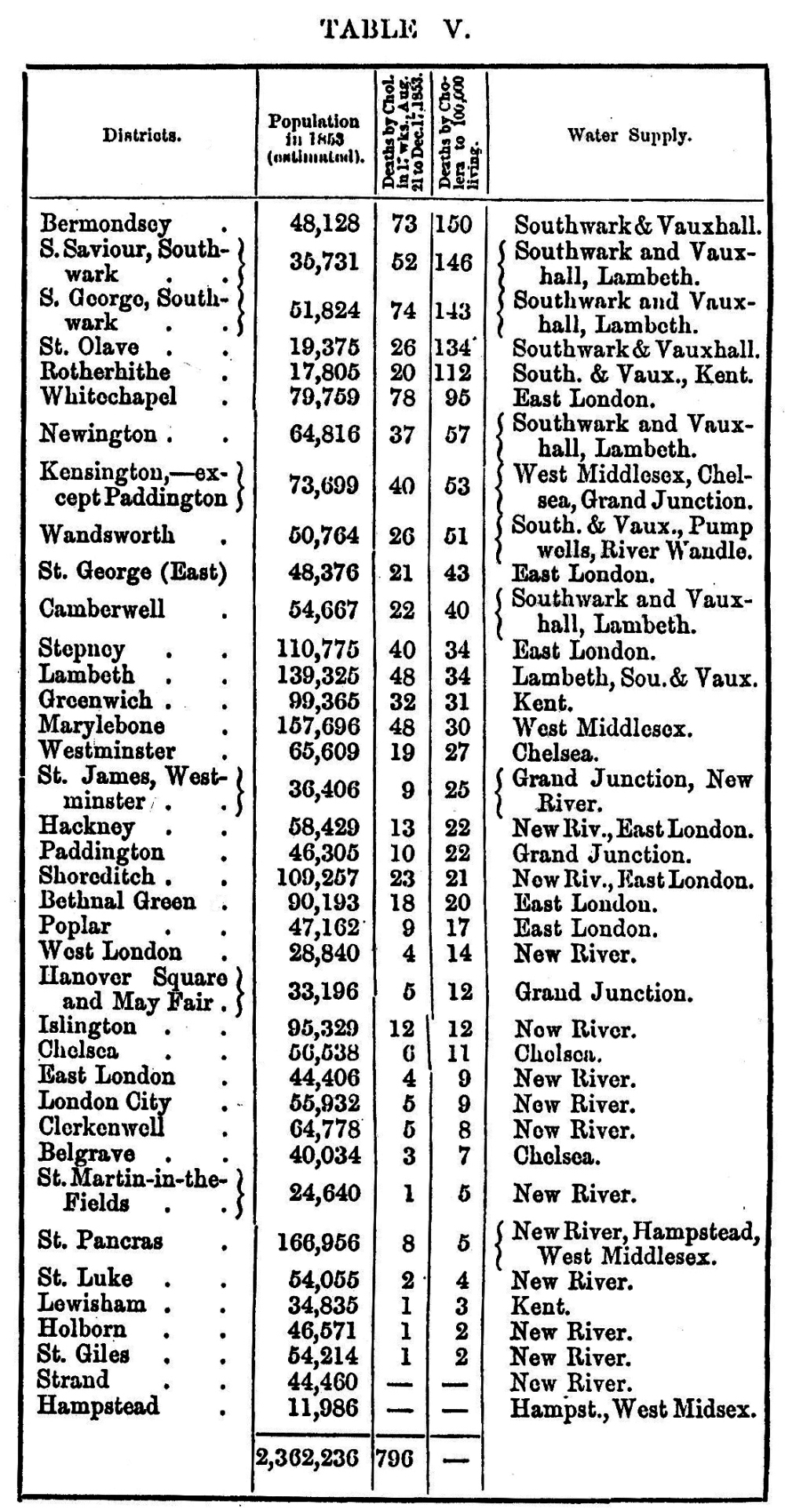

Table V showing this effect

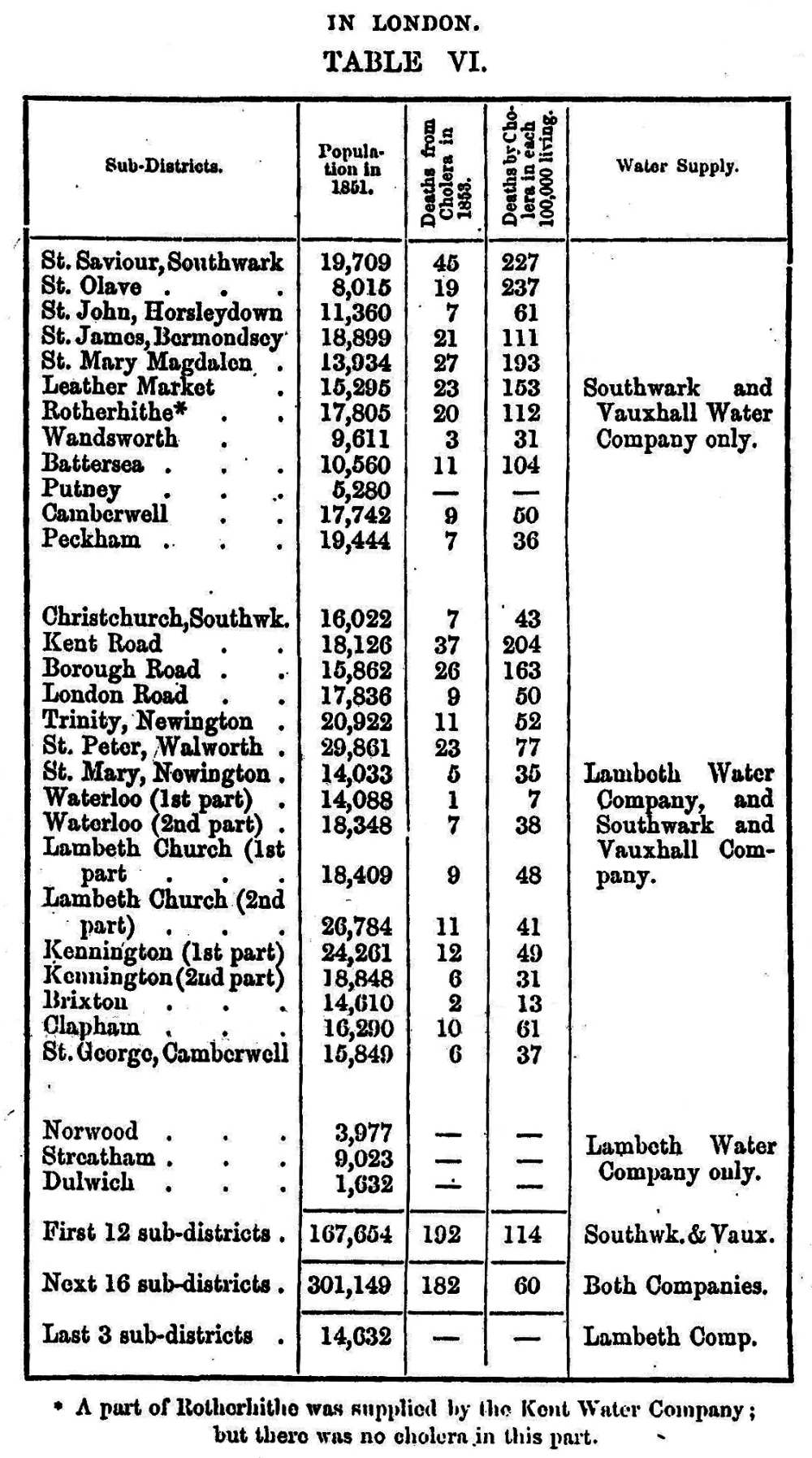

Table VI showing this effect

Intimate mixture of the water supply of the Lambeth with that of the Southwark and Vauxhall Company

Opportunity thus afforded of gaining conclusive evidence of the effect of the water supply on the mortality from cholera

Account of inquiry for obtaining this evidence

Result of the inquiry as regards the first four weeks of the epidemic in 1854

Result of the inquiry as regards the first seven weeks of the epidemic in 1854

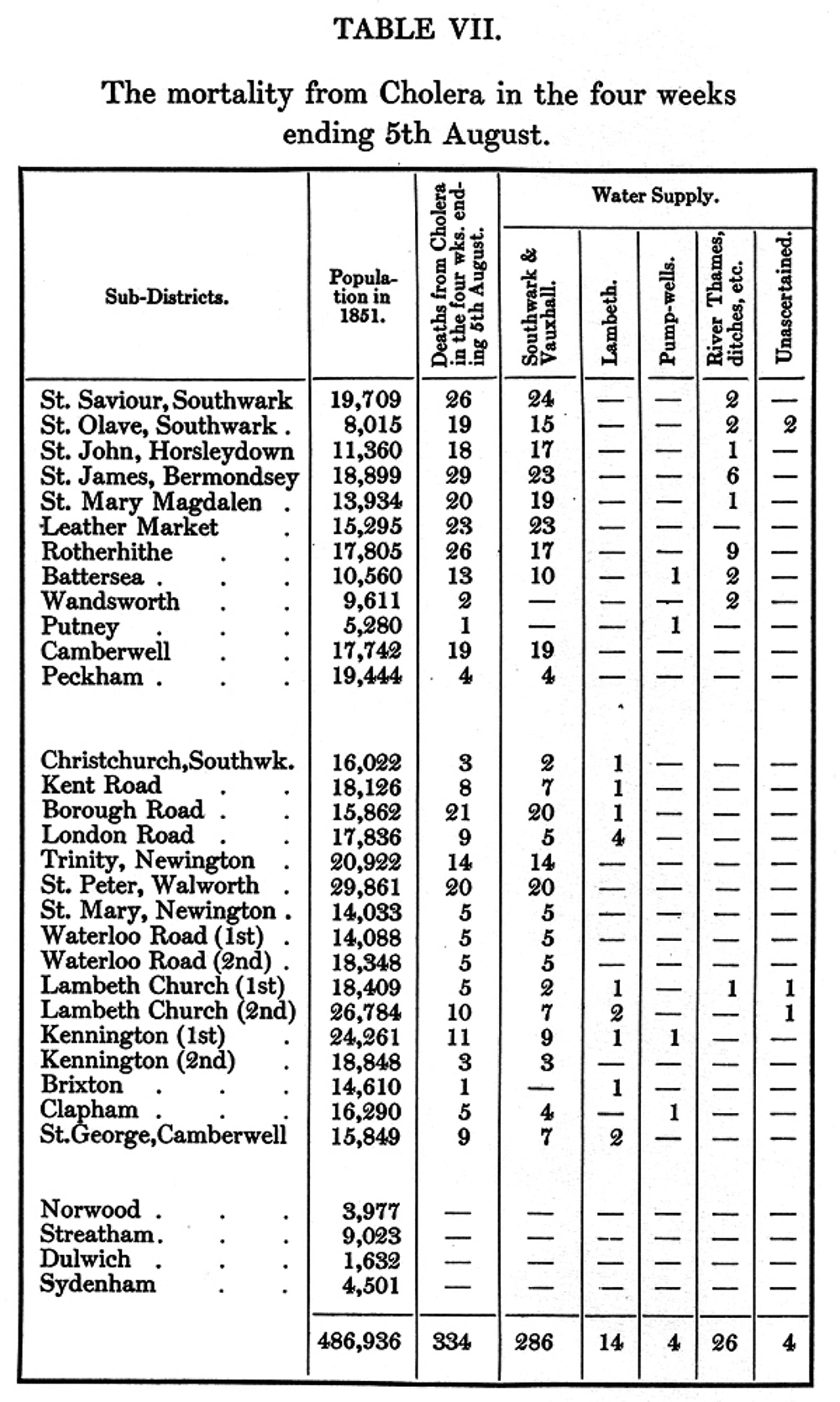

Table VII illustrating these results

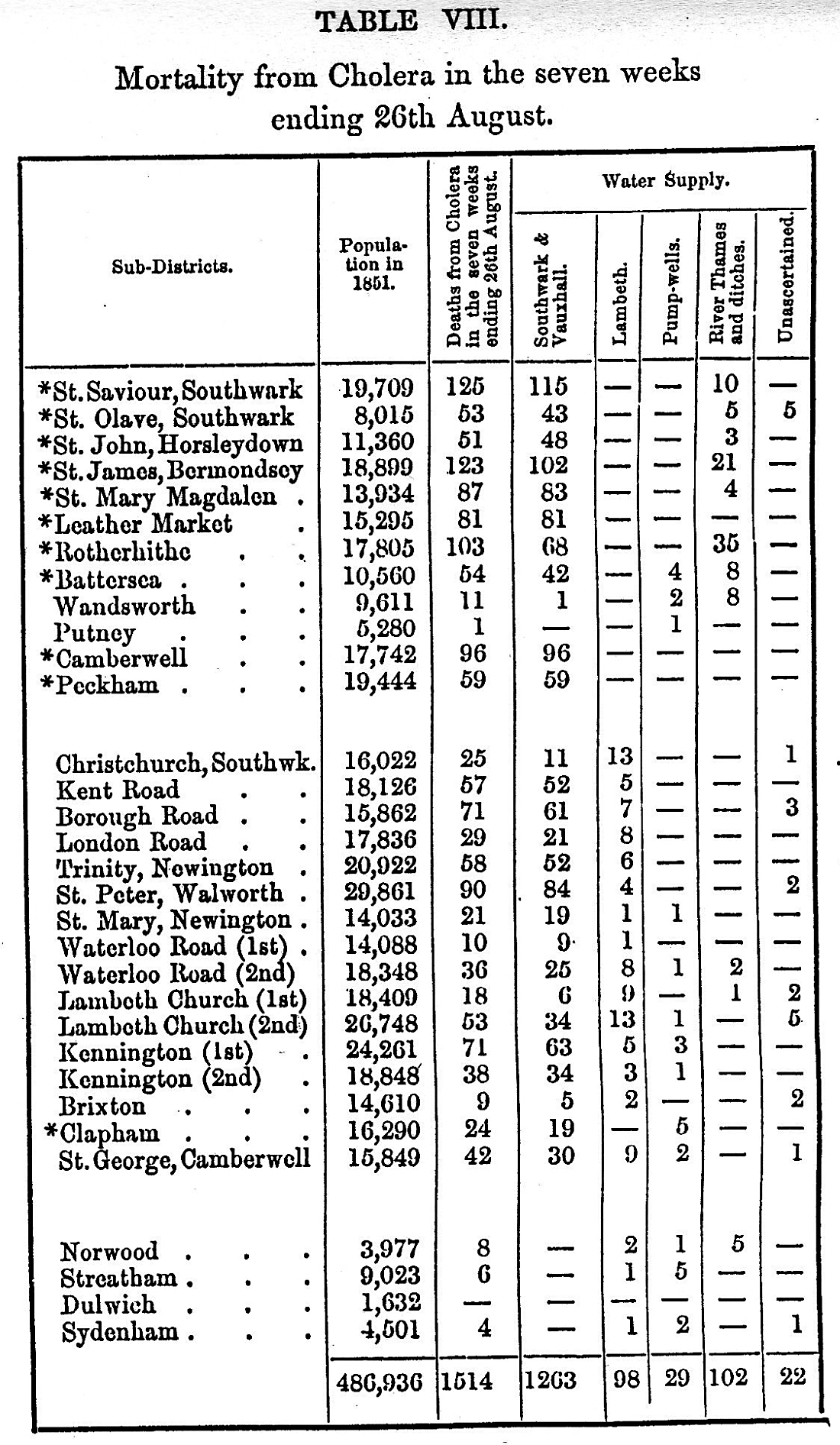

Table VIII illustrating these results

Inquiry of the Registrar-General respecting the effect of the water supply of the above-mentioned companies during the later period of the epidemic

Comparison of the mortality of 1849 and 1854, in districts supplied by the above-mentioned companies

Effect of the water supply on the mortality from cholera amongst the inmates of workhouses and prisons

Cholera in the district of the Chelsea Water Company

Effect of dry weather to increase the impurity of the Thames

Relation between the greater or less mortality from cholera in London and the less or greater elevation of the ground

This relation shown to depend on the difference of water supply at different elevations

OUTBREAK OF CHOLERA AT DEPTFORD CAUSED BY POLLUTED WATER

Just at the time when the great outbreak of cholera occurred in the neighborhood of Broad Street, Golden Square, there was an equally violent irruption in Deptford, but of a more limited extent. About ninety deaths took place in a few days, amongst two or three score of small houses, in the north end of New Street and an adjoining row called French's Fields. Deptford is supplied with very good water from the river Ravensbourne by the Kent Water Works, and until this outbreak there was but little cholera in the town, except amongst some poor people, who had no water except what they got by pailsful from Deptford Creek -- an inlet of the Thames. There had, however, been a few cases in and near New Street, just before the great outbreak. On going to the spot on September 12th and making inquiry, I found that the houses in which the deaths had occurred were supplied by the Kent Water Works, and the inhabitants never used any other water. The people informed me, however, that for some few weeks the water had been extremely offensive when first turned on; they said it smelt like a cesspool, and frothed like soap suds. They were in the habit of throwing away a few pailsful of that which first came in, and collecting some for use after it became clear. On inquiring in the surrounding streets, to which this outbreak of cholera did not extend, viz., Wellington Street, Old King Street, and Hughes's Fields, I found that there had been no alteration in the water. I concluded, therefore, that a leakage had taken place into the pipes supplying the places where the outbreak occurred, during the intervals when the water was not turned on. Gas is known to get into the water-pipes occasionally in this manner, when they are partially empty, and to impart its taste to the water. There are no sewers in New Street or French's Fields, and the refuse of all kinds consequently saturates the ground in which the pipes are laid. I found that the water collected by the people, after throwing away the first portion, still contained more organic matter than that supplied to the adjoining streets. On adding nitrate of silver and exposing the specimens to the light, a deeper tint of brown was developed in the former than in the latter.

COMMUNICATION OF CHOLERA BY MEANS OF THE WATER OF RIVERS WHICH RECEIVE THE CONTENTS OF THE SEWERS

All the instances of communication of cholera through the medium of water, above related, have resulted from the contamination of a pump-well, or some other limited supply of water; and the outbreaks of cholera connected with the contamination, though sudden and intense, have been limited also; but when the water of a river becomes infected with the cholera evacuations emptied from on board ship, or passing down drains and sewers, the communication of the disease, though generally less sudden and violent, is much more widely extended; more especially when the river water is distributed by the steam engine and pipes connected with water-works. Cholera may linger in the courts and alleys crowded with the poor, for reasons previously pointed out, but I know of no instance in which it has been generally spread through a town or neighborhood, amongst all classes of the community, in which the drinking water has not been the medium of its diffusion. Each epidemic of cholera in London has borne a strict relation to the nature of the water-supply of its different districts, being modified only by poverty, and the crowding and want of cleanliness which always attend it.

INFLUENCE OF THE WATER SUPPLY ON THE EPIDEMIC OF 1832, IN LONDON

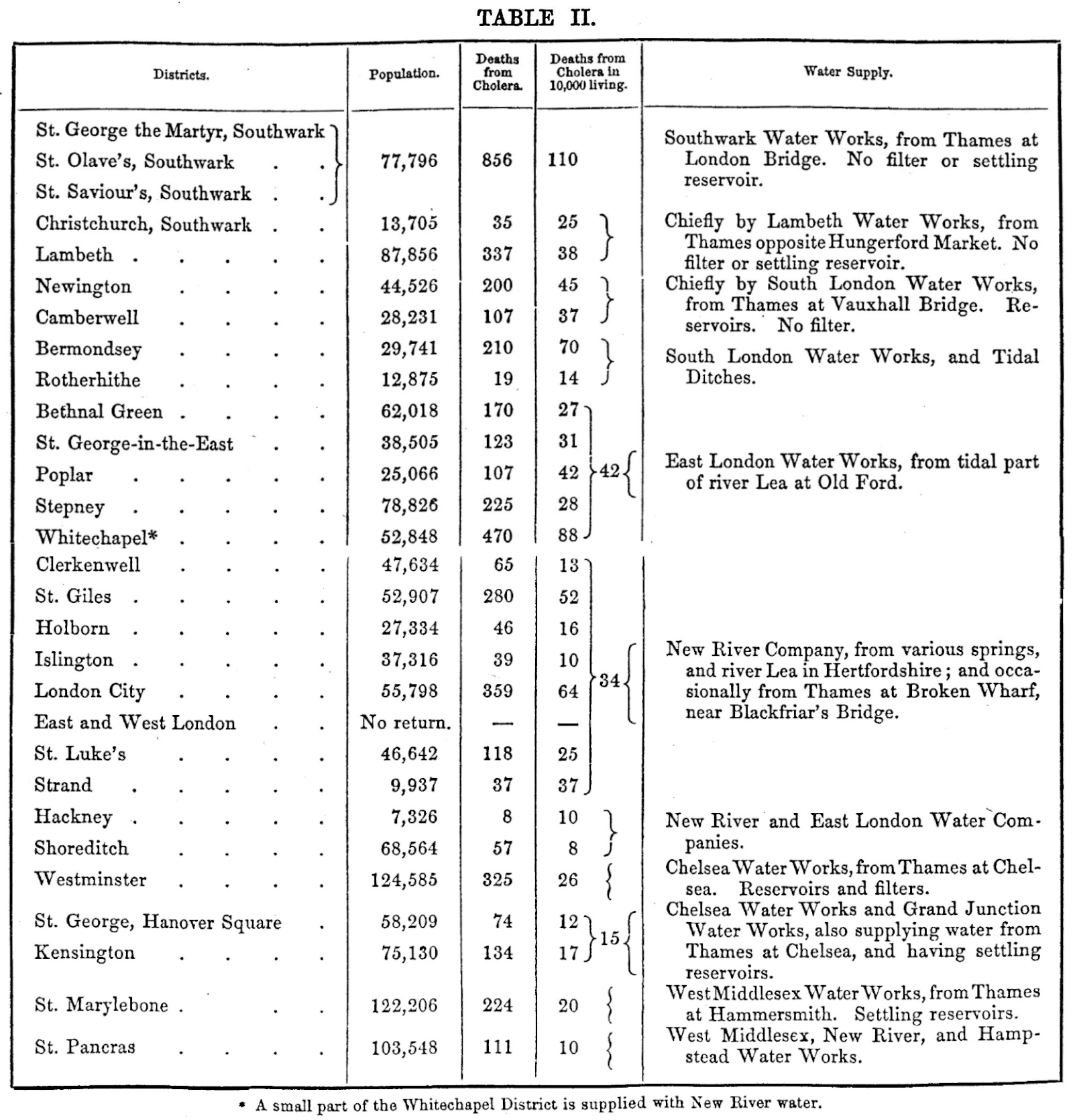

The following table shows the number of deaths from cholera in the various districts of London in 1832, together with the nature of the water supply at that period.[1]

TABLE II SHOWING THE MORTALITY FROM CHOLERA, AND THE WATER SUPPLY

This table shows that in the greater part of Southwark, which was supplied with worse water than any other part of the metropolis, the mortality from cholera was also much higher than anywhere else. The other south districts, supplied with water obtained at points higher up the Thames, and containing consequently less impurity, were less affected. On the north of the Thames, the east districts, supplied, in 1832, with water from the river Lea, at Old Ford, where it contained the sewage of a large population, suffered more than other parts on the north side of London. Whitechapel suffered more than the other east districts; probably not more from the poverty and crowded state of the population, than from the great number of mariners, coalheavers, and others, living there, who were employed on the Thames, and got their water, whilst at work, direct from the river. There were one hundred and thirty-nine deaths from cholera amongst persons afloat on the Thames. The cholera passed very lightly over most of the districts supplied by the New River Company. St Giles' was an exception, owing to the overcrowding of the common lodging-houses in the part of the parish called the Rookery. The City of London also suffered severely in 1839. Now when the engine at Broken Wharf was employed to draw water from the Thames, this water was supplied more particularly to the City, and not at all to the higher districts supplied by the New River Company. This would offer an explanation of the high mortality from cholera in the City at that time, supposing the engine were actually used during 1832; but I have not yet been able to ascertain that circumstance with certainty. I know, however, that it was still used occasionally some years later.

Westminster suffered more in 1832 than St. George, Hanover Square, and Kensington, which at that time had the same water. This arose from the poor and crowded state of part of its population. The number of cases of cholera communicated by the water would be the same in one district as in the other; but in one district the disease would spread also from person to person more than in the others.

INFLUENCE OF THE WATER SUPPLY ON THE EPIDEMIC OF 1849, IN LONDON

Between 1839 and 1849 many changes took place in the water-supply of London. The Southwark Water Company united with the South London Water Company, to form a new Company under the name of the Southwark and Vauxhall Company. The water works at London Bridge were abolished, and the united company derived their supply from the Thames at Battersea Fields, about half-a-mile above Vauxhall Bridge. The Lambeth Water Company continued to obtain their supply opposite to Hungerford Market; but they had established a small reservoir at Brixton.

But whilst these changes had been made by the water companies, changes still greater had taken place in the river, partly from the increase of population, but much more from the abolition of cesspools and the almost universal adoption of water closets in their stead. The Thames in 1849 was more impure at Battersea Fields than it had been in 1839. at London Bridge. A clause which vented the South London Water Company from laying their pipes within two miles of the Lambeth Water Works was repealed in 1834, and the two Companies were in active competition for many years, the result of which is, that the pipes of the Lambeth Water Company and those of the Southwark and Vauxhall Company pass together down all the streets of several of the south districts. As the water of both these Companies was nearly equal in its impurity in 1849, this circumstance was of but little consequence at that time; but it will be shown further on that it afterwards led to very important results.

On the north side of the Thames the Water Companies and their districts remained the same, but some alterations were made in the sources of supply. The East London Water Company ceased to obtain water at Old Ford, and got it from the river Lea, above Lea Bridge, out of the influence of the tide and free from sewage, except that from some part of Upper Clapton. The Grand Junction Company removed their works from Chelsea to Brentford, where they formed large settling reservoirs. The New River Company entirely ceased to employ the steam-engine for obtaining water from the Thames. The supply of the other Water Companies remained the same as in 1832.

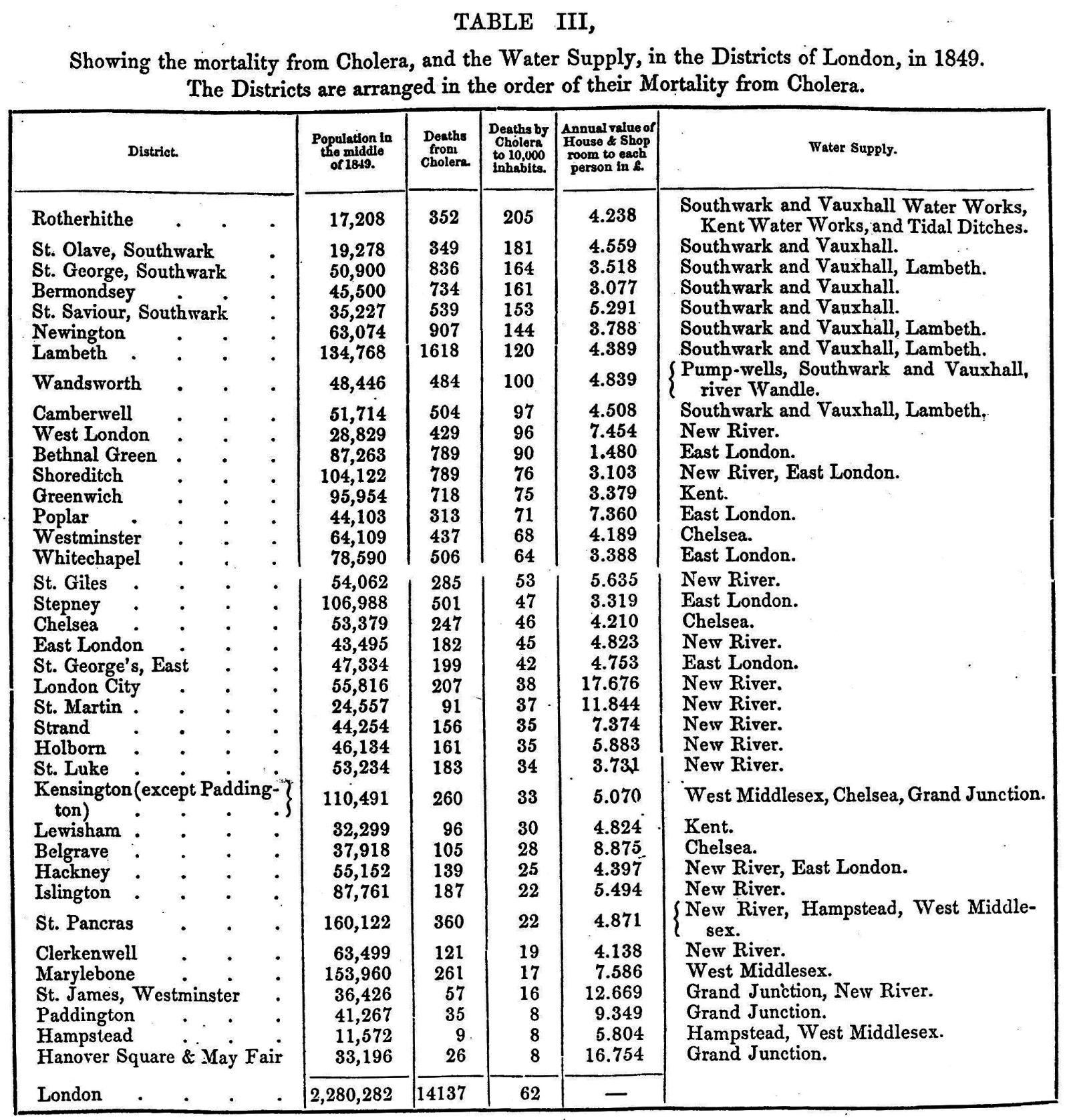

The accompanying table (No. 3), shows the mortality from cholera in the various registration districts of London in 1849, together with the water supply.

TABLE III SHOWING THIS INFLUENCE

The following table exhibits the chronological features of this terrible outbreak of cholera.

The annual value of house and shop-room for each person is also shown, as a criterion, to a great extent, of the state of overcrowding or the reverse. The deaths from cholera and the value of house-room, are taken from the "Report on the Cholera of 1849," by Dr. William Farr, of the General Register Office. The water supply is indicated merely by the name of the Companies. After the explanation given above of the source of supply, this will be sufficient. It is only necessary to add, that the Kent Water Company derive their supply from the river Ravensbourne, and the Hampstead Company from springs and reservoirs at Hampstead.

A glance at the table shows that in every district to which the supply of the Southwark and Vauxhall, or the Lambeth Water Company extends, the cholera was more fatal than in any other district whatever. The only other water company deriving a supply from the Thames, in a situation where it is much contaminated with the contents of the sewers, was the Chelsea Company. But this company, which supplies some of the most fashionable parts of London, took great pains to filter the water before its distribution, and in so doing no doubt separated, amongst other matters, the greater portion of that which causes cholera. On the other hand, although the Southwark and Vauxhall and the Lambeth Water Companies professed to filter the water, they supplied it in a most impure condition. Even in the following year, when Dr. Arthur Hill Hassall made an examination of it, he found in it the hairs of animals and numerous substances which had passed through the alimentary canal. Speaking of the water supply of London generally, Dr. Hassall says: --

"It will be observed, that the water of the companies on the Surrey side of London, viz., the Southwark, Vauxhall, and Lambeth, is by far the worst of all those who take their supply from the Thames." [2]

In the north districts of London, which suffered much less from cholera than the south districts, the mortality was chiefly influenced by the poverty and crowding of the population. The New River Company having entirely left off the use of their engine in the city, their water, being entirely free from sewage, could have had no share in the propagation of cholera. It is probable also, that the water of the East London Company, obtained above Lea Bridge, had no share in propagating the malady; and that this is true also of the West Middlesex Company, obtaining their supply from the Thames at Hammersmith; and of the Grand Junction Company, obtaining their supply at Brentford. All these Water Companies have large settling reservoirs. It is probable also, as I stated above, that the Chelsea Company in 1849, by careful filtration and by detaining the water in their reservoirs, rendered it in a great degree innocuous.

ome parts of London suffered by the contamination of the pump-wells in 1849, and the cholera in the districts near the river was increased by the practice, amongst those who are occupied on the Thames, of obtaining water to drink by dipping a pail into it. It will be shown further on, that persons occupied on the river suffered more from cholera than others. Dr. Baly makes the following inquiry in his Report to the College of Physicians.[3]

"How did it happen, if the character of the water has a great influence on the mortality from cholera, that in the Belgrave district only 28 persons in 10,000 died, and in the Westminster district, also supplied by the Chelsea Company, 68 persons in 10,000; and, again, that in the Wandsworth district the mortality was only 100, and in the district of St. Olave 181 in 10,000 inhabitants -- both these districts receiving their supply from the Southwark Company?"

The water of the Chelsea Company has been alluded to above, but whether this water had any share in the propagation of cholera or not, it is perfectly in accordance with the mode of communication of the disease which I am advocating, that it should spread more in the crowded habitations of the poor, in Westminster, than in the commodious houses of the Belgrave district. In examining the effect of polluted water as a medium of the cholera poison, it is necessary to bear constantly in mind the more direct way in which the poison is also swallowed, as I explained in the commencement of this work. As regards St. Olave's and Wandsworth, Dr. Baly was apparently not aware that, whilst almost every house in the first of these districts is supplied by the water company, and has no other supply, the pipes of the company extend to only a part of the Wandsworth district, a large part of it having only pump-wells.

COMMUNICATION OF CHOLERA BY THAMES WATER IN THE AUTUMN OF 1848

The epidemic of 1849 was a continuance or revival of that which commenced in the autumn of 1848, and there are some circumstances connected with the first cases which are very remarkable, and well worthy of notice. It has been already stated that the first case of decided Asiatic cholera in London, in the autumn of 1848, was that of a seaman from Hamburgh, and that the next case occurred in the very room in which the first patient died. These cases occurred in Horsleydown, close to the Thames. In the evening of the day on which the second case occurred in Horsleydown, a man was taken ill in Lower Fore Street, Lambeth, and died on the following morning. At the same time that this case occurred in Lambeth, the first of a series of cases occurred in White Hart Court, Duke Street, Chelsea, near the river. A day or two afterwards, there was a case at 3, Harp Court, Fleet Street. The next case occurred on October 2nd, on board the hulk Justitia, lying off Woolwich; and the next to this in Lower Fore Street, Lambeth, three doors from where a previous case had occurred. The first thirteen cases were all situated in the localities just mentioned; and on October 5th there were two cases in Spitalfields.

Now, the people in Lower Fore Street, Lambeth, obtained their water by dipping a pail into the Thames, there being no other supply in the street. In White Hart Court, Chelsea, the inhabitants obtained water for all purposes in a similar way. A well was afterwards sunk in the court; but at the time these cases occurred the people had no other means of obtaining water, as I ascertained by inquiry on the spot. The inhabitants of Harp Court, Fleet Street, were in the habit, at that time, of procuring water from St. Bride's pump, which was afterwards closed on the representation of Mr. Hutchinson, surgeon, of Farringdon Street, in consequence of its having been found that the well had a communication with the Fleet Ditch sewer, up which the tide flows from the Thames. I was informed by Mr. Dabbs, that the hulk Justitia was supplied with spring-water from the Woolwich Arsenal; but it is not improbable that water was occasionally taken from the Thames alongside, as was constantly the practice in some of the other hulks, and amongst the shipping generally.

When the epidemic revived again in the summer of 1849, the first case in the sub-district "Lambeth; Church, 1st part," was in Lower Fore Street, on June 27th; and on the commencement of the epidemic of the present year, the first case of cholera in any part of Lambeth, and one of the earliest in London, occurred at 52, Upper Fore Street, where also the people had no water except what they obtained from the Thames with a pail, as I ascertained by calling at the house. Many of the earlier cases this year occurred in persons employed amongst the shipping in the river, and the earliest cases in Wandswroth and Battersea have generally been amongst persons getting water direct from the Thames, or from streams up which the Thames flows with the tide. It is quite in accordance with what might be expected from the propagation of cholera through the medium of the Thames water, that it should generally affect those who draw it directly from the river somewhat sooner than those who receive it by the more circuitous route of the pipes of a water company.

NEW WATER SUPPLY OF THE LAMBETH COMPANY

London was without cholera from the latter part of 1849 to August 1853. During this interval an important change had taken place in the water supply of several of the south districts of London. The Lambeth Company removed their water works, in 1852, from opposite Hungerford Market to Thames Ditton; thus obtaining a supply of water quite free from the sewage of London. The districts supplied by the Lambeth Company are, however, also supplied, to a certain extent, by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, the pipes of both companies going down every street, in the places where the supply is mixed, as was previously stated. In consequence of this intermixing of the water supply, the effect of the alteration made by the Lambeth Company on the progress of cholera was not so evident, to a cursory observer, as it would otherwise have been. It attracted the attention, however, of the Registrar-General, who published a table in the " Weekly Return of Births and Deaths" for 26th November 1853, of which the following is an abstract, containing as much as applies to the south districts of London.

EFFECT OF THIS NEW SUPPLY IN THE EPIDEMIC OF AUTUMN 1853

It thus appears that the districts partially supplied with the improved water suffered much less than the others, although, in 1849, when the Lambeth Company obtained their supply opposite Hungerford Market, these same districts suffered quite as much as those supplied entirely by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, as was shown in Table III. The Lambeth water extends to only a small portion of some of the districts necessarily included in the groups supplied by both Companies; and when the division is made a little more in detail, by taking sub-districts instead of districts, the effect of the new water supply is shown to be greater than appears in the above table. The Kent Water Company was introduced into the table by the Registrar-General on account of its supplying a small part of Rotherhithe. The following interesting remarks appeared, respecting this portion of Rotherhithe, in the " Weekly Return" of December 10, 1853:--

"Southwark and Vauxhall Water Comany.-- The following is an extract from a letter which the Registrar-General has received from Mr. Pitt, the Registrar of Rotherhithe:--

" 'I consider Mr. Morris's description of the part of the parish through which the pipes of the Kent Water Company were laid in 1849, is in the main correct; for though the Company had entered the parish, the water was but partially taken by the inhabitants up to the time of the fearful visitation in the above year.'

" ' With respect to the deaths in 1849, they were certainly more numerous in the district now generally supplied by the Kent Company than in any other part of the parish. I only need mention Charlotte Row, Ram Alley, and Silver Street, -- places where the scourge fell with tremendous severity.'

" 'Among the recent cases of cholera, not one has occurred in the district supplied by the Kent Water Company.'

" 'The parish of Rotherhithe has been badly supplied with water for many ages past. The people drank from old wells, old pumps, open ditches, and the muddy stream of the Thames.'

" 'In 1848-9 the mortality from cholera in Rotherhithe was higher than it was in any other district of London. This is quite in conformity with the general rule, that when cholera prevails, it is most fatal where the waters are most impure.'"

TABLE V SHOWING THIS EFFECT

The following table (which, with a little alteration in the arrangement, is taken from the "Weekly Return of Births and Deaths" for 31st December 1853) shows the mortality from cholera, in the epidemic of 1853, down to a period when the disease had almost disappeared.

The districts are arranged in the order of their mortality from Cholera.

It will be observed that Lambeth, which is supplied with water in a great measure by the Lambeth Company, occupies a lower position in the above table than it did in the previous table showing the mortality in 1849. Rotherhithe also has been removed from the first to the fifth Place; owing, no doubt, to the portion of the district supplied with water from the Kent Water Works, instead of the ditches, being altogether free from the disease, as was noticed above.

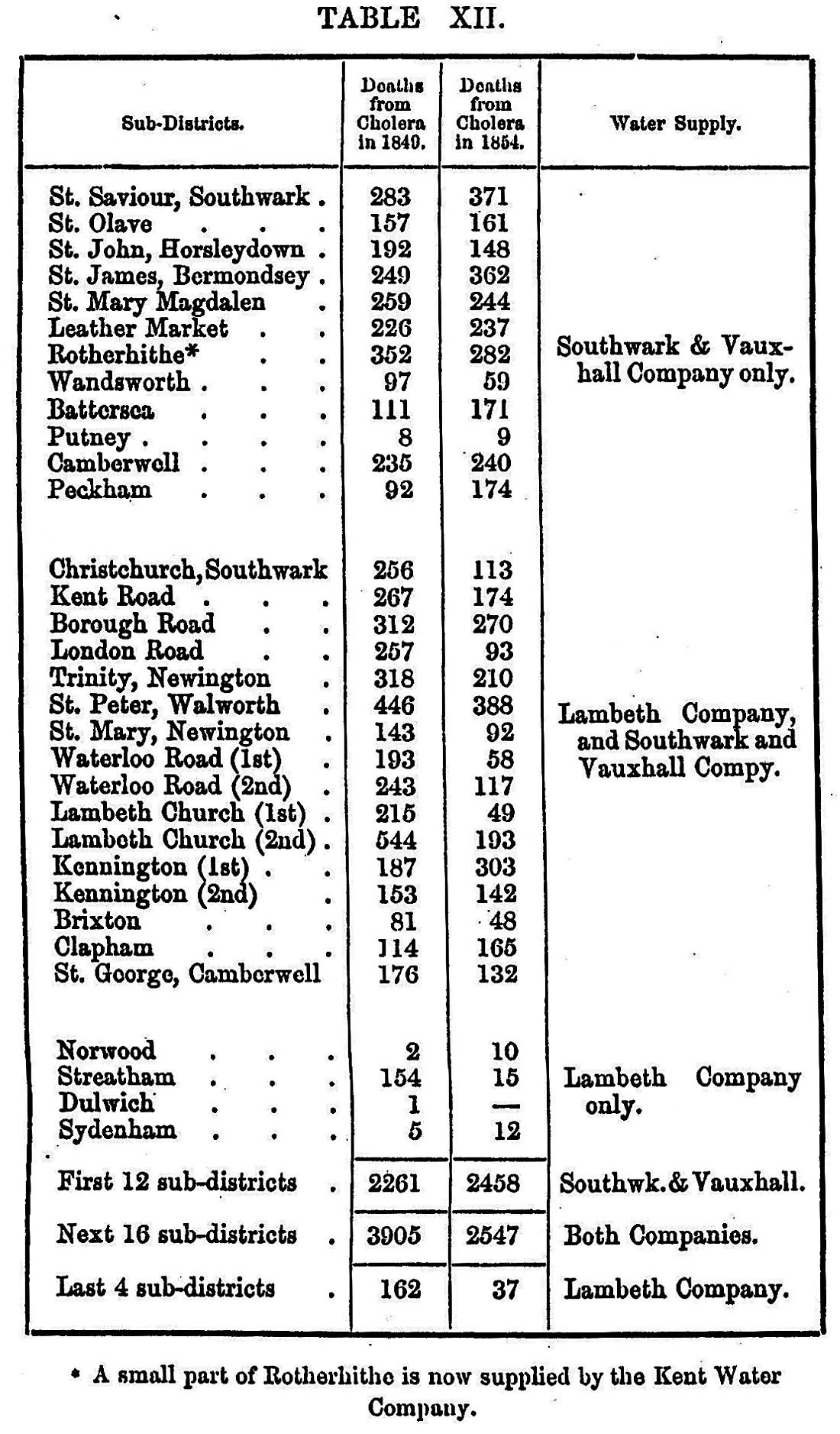

As the Registrar-General published a list of all the deaths from cholera which occurred in London in 1853, from the commencement of the epidemic in August to its conclusion in January 1854, I have been able to add up the number which occurred in the various sub-districts on the south side of the Thames, to which the water supply of the Southwark and Vauxhall, and the Lambeth Companies, extends. I have presented them in the table opposite, arranged in three groups.

TABLE VI SHOWING THIS EFFECT

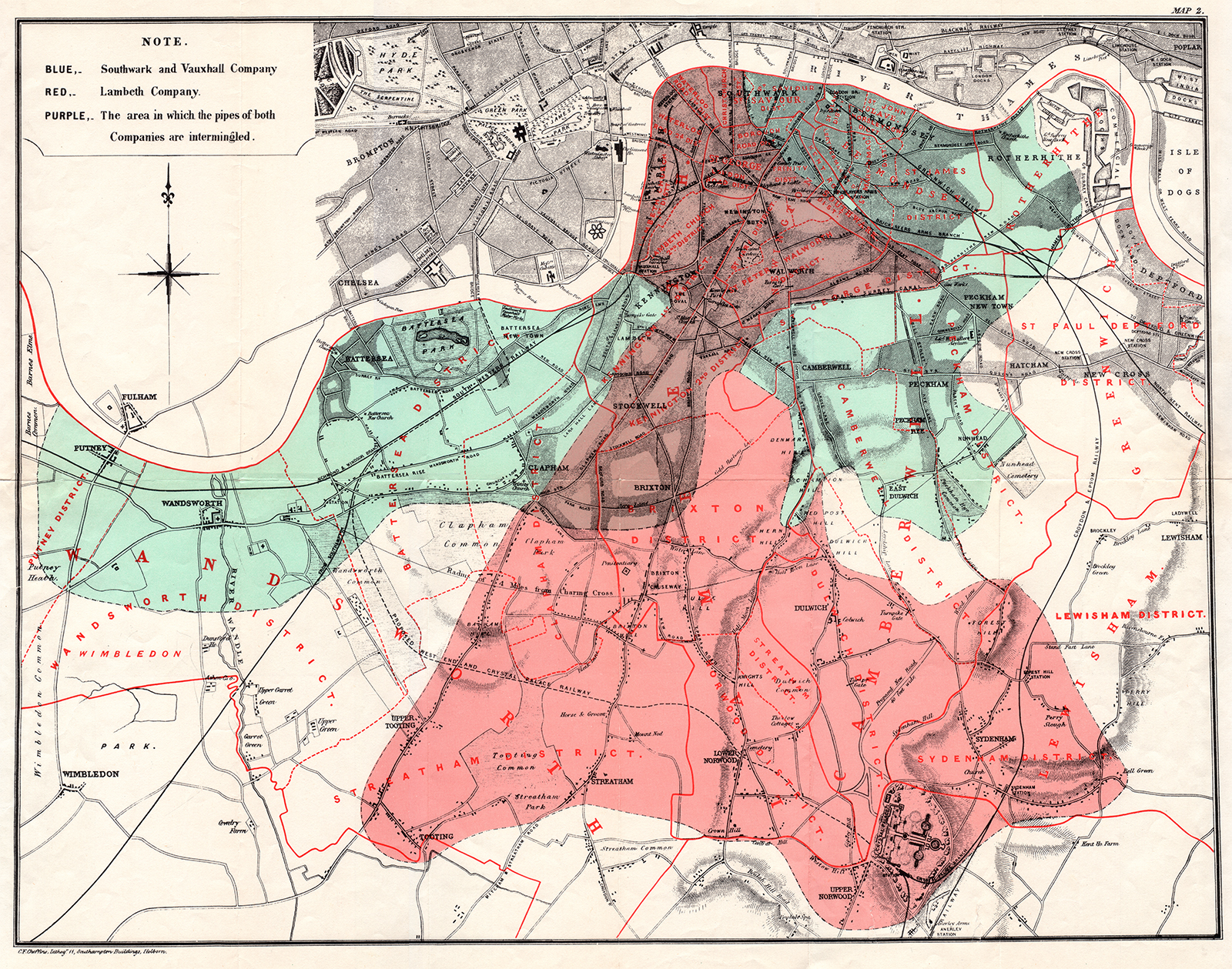

Besides the general result shown in the table, there are some particular facts well worthy of consideration. In 1849, when the water of the Lambeth Company was quite as impure as that of the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, the parish of Christchurch suffered a rather higher rate of mortality from cholera than the adjoining parish of St. Saviour; but in 1853, whilst the mortality in St. Saviour's was at the rate of two hundred and twenty-seven to one hundred thousand living, that of Christchurch was only at the rate of forty-three. Now St. Saviour's is supplied with water entirely by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, and Christchurch is chiefly supplied by the Lambeth Company. The pipes and other property of the Lambeth Company, in the parish of Christchurch, are rated at about 3l6 pounds, whilst the property of the Southwark and Vauxhall Company in this parish is only rated at about 108 pounds. Waterloo Road, 1st part, suffered almost as much as St. Saviour's in 1849, and had but a single death in 1853; it is supplied almost exclusively by the Lambeth Company. The sub-districts of Kent Road and Borough Road, which suffered severely from cholera, are supplied, through a great part of their extent, exclusively by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company; the supply of the Lambeth Company being intermingled with that of the other only in a part of these districts, as may be seen by consulting the accompanying map (No. II).

MAP II (note: blue has faded to green)

The rural districts of Wandsworth and Peckham contain a number of pump-wells, and are only partially supplied by the Water Company; on this account they suffered a lower mortality than the other sub-districts supplied with the water from Battersea Fields. In the three sub-districts to which this water does not extend, there was no death from cholera in 1853.

INTIMATE MIXTURE OF THE WATER SUPPLY OF THE LAMBETH WITH THAT OF THE SOUTHWARK AND VAUXHALL COMPANY

Although the facts shown in the above table afford very strong evidence of the powerful influence which the drinking of water containing the sewage of a town exerts over the spread of cholera, when that disease is present, yet the question does not end here; for the intermixing of the water supply of the Southwark and Vauxhall Company with that of the Lambeth Company, over an extensive part of London, admitted of the subject being sifted in such a way as to yield the most incontrovertible proof on one side or the other. In the sub-districts enumerated in the above table as being supplied by both Companies, the mixing of the supply is of the most intimate kind. The pipes of each Company go down all the streets, and into nearly all the courts and alleys. A few houses are supplied by one Company and a few by the other, according to the decision of the owner or occupier at that time when the Water Companies were in active competition. In many cases a single house has a supply different from that on either side. Each company supplies both rich and poor, both large houses and small; there is no difference either in the condition or occupation of the persons receiving the water of the different Companies. Now it must be evident that, if the diminution of cholera, in the districts partly supplied with the improved water, depended on this supply, the houses receiving it would be the houses enjoying the whole benefit of the diminution of the malady, whilst the houses supplied with the water from Battersea Fields would suffer the same mortality as they would if the improved supply did not exist at all. As there is no difference whatever, either in the houses or the people receiving the supply of the two Water Companies, or in any of the physical conditions with which they are surrounded, it is obvious that no experiment could have been devised which would more thoroughly test the effect of water supply on the progress of cholera than this, which circumstances placed ready made before the observer.

OPPORTUNITY THUS AFFORDED OF GAINING CONCLUSIVE EVIDENCE OF THE EFFECT OF THE WATER SUPPLY ON THE MORTALITY FROM CHOLERA

The experiment, too, was on the grandest scale. No fewer than three hundred thousand people of both sexes, of every age and occupation, and of every rank and station, from gentlefolks down to the very poor, were divided into two groups without their choice, and, in most cases, without their knowledge; one group being supplied with water containing the sewage of London, and, amongst it, whatever might have come from the cholera patients, the other group having water quite free from such impurity.

To turn this grand experiment to account, all that was required was to learn the supply of water to each individual house where a fatal attack of cholera might occur. I regret that, in the short days at the latter part of last year, I could not spare the time to make the inquiry; and, indeed, I was not fully aware, at that time, of the very intimate mixture of the supply of the two Water Companies, and the consequently important nature of the desired inquiry.

When the cholera returned to London in July of the present year, however, I resolved to spare no exertion which might be necessary to ascertain the exact effect of the water supply on the progress of the epidemic, in the places where all the circumstances were so happily adapted for the inquiry. I was desirous of making the investigation myself, in order that I might have the most satisfactory proof of the truth or fallacy of the doctrine which I had been advocating for five years. I had no reason to doubt the correctness of the conclusions I had drawn from the great number of facts already in my possession, but I felt that the circumstance of the cholera-poison passing down the sewers into a great river, and being distributed through miles of pipes, and yet producing its specific effects, was a fact of so startling a nature, and of so vast importance to the community, that it could not be too rigidly examined, or established on too firm a basis.

I accordingly asked permission at the General Register Office to be supplied with the addresses of persons dying of cholera, in those districts where the supply of the two Companies is intermingled in the manner I have stated above. Some of these addresses were published in the "Weekly Returns," and I was kindly permitted to take a copy of others. I commenced my inquiry about the middle of August with two sub-districts of Lambeth, called Kennington, first part, and Kennington, second part. There were forty-four deaths in these sub-districts down to 12th August, and I found that thirty-eight of the houses in which these deaths occurred were supplied with water by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, four houses were supplied by the Lambeth Company, and two had pump-wells on the premises and no supply from either of the Companies.

ACCOUNT OF THE INQUIRY FOR OBTAINING THIS EVIDENCE

As soon as I had ascertained these particulars I communicated them to Dr. William Farr, who was much struck with the result, and at his suggestion the Registrars of all the south districts of London were requested to make a return of the water supply of the house in which the attack took place, in all cases of death from cholera. This order was to take place after the 26th August, and I resolved to carry my inquiry down to that date, so that the facts might be ascertained for the whole course of the epidemic. I pursued my inquiry over the various other sub-districts of Lambeth, Southwark, and Newington, where the supply of the two Water Companies is intermixed, with a result very similar to that already given, as will be seen further on. In cases where persons had been removed to a workhouse or any other place, after the attack of cholera had commenced, I inquired the water supply of the house where the individuals were living when the attack took place.

The inquiry was necessarily attended with a good deal of trouble. There were very few instances in which I could at once get the information I required. Even when the water-rates are paid by the residents, they can seldom remember the name of the Water Company till they have looked for the receipt. In the case of working people who pay weekly rents, the rates are invariably paid by the landlord or his agent, who often lives at a distance, and the residents know nothing about the matter. It would, indeed, have been almost impossible for me to complete the inquiry, if I had not found that I could distinguish the water of the two companies with perfect certainty by a chemical test. The test I employed was founded on the great difference in the quantity of chloride of sodium contained in the two kinds of water, at the time I made the inquiry. On adding solution of nitrate of silver to a gallon of the water of the Lambeth Company, obtained at Thames Ditton, beyond the reach of the sewage of London, only 2.28 grains of chloride of silver were obtained, indicating the presence of 0.95 grains of chloride of sodium in the water. On treating the water of the Southwark and Vauxhall Company in the same manner, 91 grains of chloride of silver were obtained, showing the presence of 37.9 grains of common salt per gallon. Indeed, the difference in appearance on adding nitrate of silver to the two kinds of water was so great, that they could be at once distinguished without any further trouble. Therefore when the resident could not give clear and conclusive evidence about the Water Company, I obtained some of the water in a small phial, and wrote the address on the cover, when I could examine it after coming home. The mere appearance of the water generally afforded a very good indication of its source, especially if it was observed as it came in, before it had entered the water-butt or cistern ; and the time of its coming in also afforded some evidence of the kind of water, after I had ascertained the hours when the turncocks of both Companies visited any street. These points were, however, not relied on, except as corroborating more decisive proof, such as the chemical test, or the Company's receipt for the rates.

A return had been made to Parliament of the entire number of houses supplied with water by each of the Water Companies, but as the number of houses which they supplied in particular districts was not stated, I found that it would be necessary to carry my inquiry into all the districts to which the supply of either Company extends, in order to show the full bearing of the facts brought out in those districts where the supply is intermingled. I inquired myself respecting every death from cholera in the districts to which the supply of the Lambeth Company extends, and I was fortunate enough to obtain the assistance of a medical man, Mr. John Joseph Whiting, L.A.C., to make inquiry in Bermondsey, Rotherhithe, Wandsworth, and certain other districts, which are supplied only by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company. Mr. Whiting took great pains with his part of the inquiry, which was to ascertain whether the houses in which the fatal attacks took place were supplied with the Company's water, or from a pump-well, or some other source.

RESULT OF THE INQUIRY AS REGARDS THE FIRST FOUR WEEKS OF THE EPIDEMIC OF 1854

Mr. Whiting's part of the investigation extended over the first four weeks of the epidemic, from 8th July to 5th August; and as inquiry was made respecting every death from cholera during this part of the epidemic, in all the districts to which the supply of either of the Water Companies extends, it may be well to consider this period first. There were three hundred and thirty-four deaths from cholera in these four weeks, in the districts to which the water supply of the Southwark and Vauxhall and the Lambeth Company extends. Of these it was ascertained, that in two hundred and eighty-six cases the house where the fatal attack of cholera took place was supplied with water by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, and in only fourteen cases was the house supplied with the Lambeth Company's water; in twenty-two cases the water was obtained by dipping a pail directly into the Thames, in four instances it was obtained from pump-wells, in four instances from ditches, and in four cases the source of supply was not ascertained, owing to the person being taken ill whilst traveling, or from some similar cause. The particulars of all the deaths which were caused by cholera in the first four weeks of the late epidemic, were published by the Registrar-General in the "Weekly Returns of Births and Deaths in London," and I have had the three hundred and thirty-four above enumerated reprinted in an appendix to this edition, as a guarantee that the water supply was inquired into, and to afford any person who wishes it an opportunity of verifying the result. Any one who should make the inquiry must be careful to find the house where the attack took place, for in many streets there are several houses having the same number.

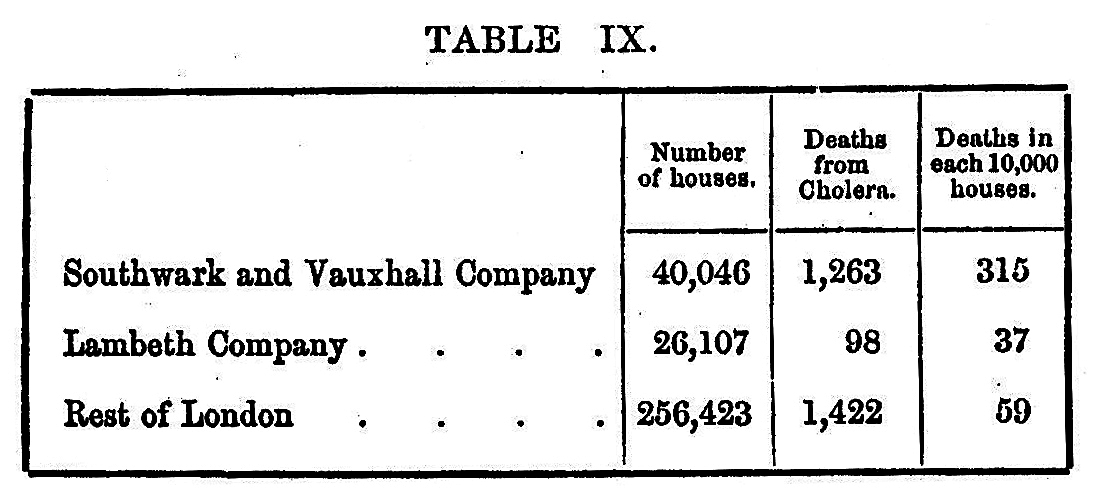

According to a return which was made to Parliament, the Southwark and Vauxhall Company supplied 40,046 houses from January 1st to December 31st, 1853, and the Lambeth Company supplied 26,107 houses during the same period; consequently, as 286 fatal attacks of cholera took place, in the first four weeks of the epidemic, in houses supplied by the former Company, and only 14 in houses supplied by the latter, the proportion of fatal attacks to each 10,000 houses was as follows. Southwark and Vauxhall 71. Lambeth 5. The cholera was therefore fourteen times as fatal at this period, amongst persons having the impure water of the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, as amongst those having the purer water from Thames Ditton.

It is extremely worthy of remark, that whilst only five hundred and sixty-three deaths from cholera occurred in the whole of the metropolis, in the four weeks ending 5th August, more than one half of them took place amongst the customers of the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, and a great portion of the remaining deaths were those of mariners and persons employed amongst the shipping in the Thames, who almost invariably draw their drinking water direct from the river.

It may, indeed, be confidently asserted, that if the Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company had been able to use the same expedition as the Lambeth Company in completing their new works, and obtaining water free from the contents of sewers, the late epidemic of cholera would have been confined in a great measure to persons employed among the shipping, and to poor people who get water by pailsful direct from the Thames or tidal ditches.

The number of houses in London at the time of the last census was 327,391. If the houses supplied with water by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, and the deaths from cholera occurring in these houses, be deducted, we shall have in the remainder of London 287,345 houses, in which 277 deaths from cholera took place in the first four weeks of the epidemic. This is at the rate of nine deaths to each 10,000. But the houses supplied with water by the Lambeth Company only suffered a mortality of five in each 10,000 at this period; it follows, therefore, that these houses, although intimately mixed with those of the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, in which so great a proportional mortality occurred, did not suffer even so much as the rest of London which was not so situated.

In the beginning of the late epidemic of cholera in London, the Thames water seems to have been the great means of its diffusion, either through the pipes of the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, or more directly by dipping a pail in the river. Cholera was prevailing in the Baltic Fleet in the early part of summer, and the following passage from the "Weekly Returns" of the Registrar-General shows that the disease was probably imported thence to the Thames.

"Bermondsey, St. James. At 10, Marine Street, on 25th July, a mate mariner, aged 34 years, Asiatic cholera 101 hours, after premonitory diarrhea 16.5 hours. The medical attendant states: 'This patient was the chief mate to a steam-vessel taking stores to and bringing home invalids from the Baltic Fleet. Three weeks ago he brought home in his cabin the soiled linen of an officer who had been ill. The linen was washed and returned.' "

The time when this steam-vessel arrived in the Thames with the soiled linen on board, was a few days before the first cases of cholera appeared in London, and these first cases were chiefly amongst persons connected with the shipping in the river. It is not improbable therefore that a few simple precautions, with respect to the communications with the Baltic Fleet, might have saved London from the cholera this year, or at all events greatly retarded its appearance.

RESULT OF THE INQUIRY AS REGARDS THE FIRST SEVEN WEEKS OF THE EPIDEMIC OF 1854

As the epidemic advanced, the disproportion between the number of cases in houses supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company and those supplied by the Lambeth Company, became not quite so great, although it continued very striking. In the beginning of the epidemic the cases appear to have been almost altogether produced through the agency of the Thames water obtained amongst the sewers; and the small number of cases occurring in houses not so supplied, might be accounted for by the fact of persons not keeping always at at home and taking all their meals in the houses in which they live; but as the epidemic advanced it would necessarily spread amongst the customers of the Lambeth Company, as in parts of London where the water was not in fault, by all the usual means of its communication. The two subjoined tables, VII and VIII, show the number of fatal attacks in houses supplied respectively by the two Companies, in all the sub-districts to which their water extends. The cases in table VII, are again included in the larger number which appear in the next table. The sub-districts are arranged in three groups, as they were in table VI, illustrating the epidemic of 1853.

TABLE VII ILLUSTRATING THESE RESULTS

TABLE VIII ILLUSTRATING THESE RESULTS

In table VIII, showing the mortality in the first seven weeks of the epidemic, the water supply is the result of my own personal inquiry, in every case, in all the sub-districts to which the supply of the Lambeth Company extends; but in some of the subdistricts supplied only by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, the inquiry of Mr. Whiting having extended only to 5th August, the water supply of the last three weeks is calculated to have been in the same proportion by the Company, or by pump wells, etc., as in the first four weeks, -- a calculation which is perfectly fair, and must be very near the truth. The sub-districts in which the supply is partly founded on computation, are marked with an asterisk.

The numbers in table VIII differ a very little from those of the table I communicated to the Medical Times and Gazette of 7th October, on account of the water supply having since been ascertained in some cases in which I did not then know it. The small number of instances in which the water supply remains unascertained are chiefly those of persons taken into a workhouse without their address being known.

The following is the proportion of deaths to 10,000 houses, during the first seven weeks of the epidemic, in the population supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, in that supplied by the Lambeth Company, and in the rest of London.

The mortality in the houses supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company was therefore between eight and nine times as great as in the houses supplied by the Lambeth Company; and it will be remarked that the customers of the Lambeth Company continued to enjoy an immunity from cholera greater than the rest of London which is not mixed up as they are with the houses supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company.

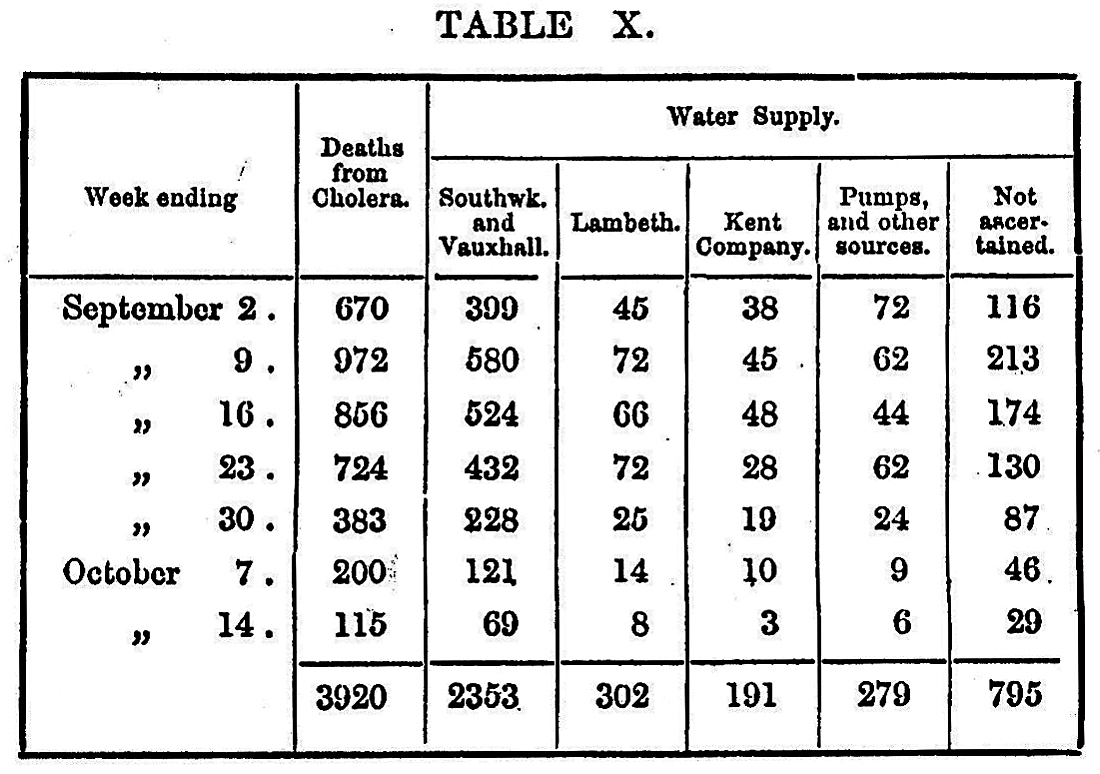

As regards the period of the epidemic subsequent to the 26th August to which my inquiry extended, I have stated that the Registrar General requested the District Registrars to make a return of the water supply of the house of attack in all cases of death from cholera. Owing to difficulties such as I explained that I had met with in the beginning of my inquiry, the Registrars could not make the return in all cases, and as they could not be expected to seek out the landlord or his agent, or to apply chemical tests to the water as I had done, the water supply remaining unascertained in a number of cases, but the numbers may undoubtedly be considered to show the correct proportions as far as they extend, and they agree entirely with the results of my inquiry respecting the earlier part of the epidemic given above.

INQUIRY OF THE REGISTRAR-GENERAL RESPECTING THE EFFECT OF THE WATER SUPPLY OF THE ABOVE-MENTIONED COMPANIES DURING THE LATER PERIOD OF THE EPIDEMIC

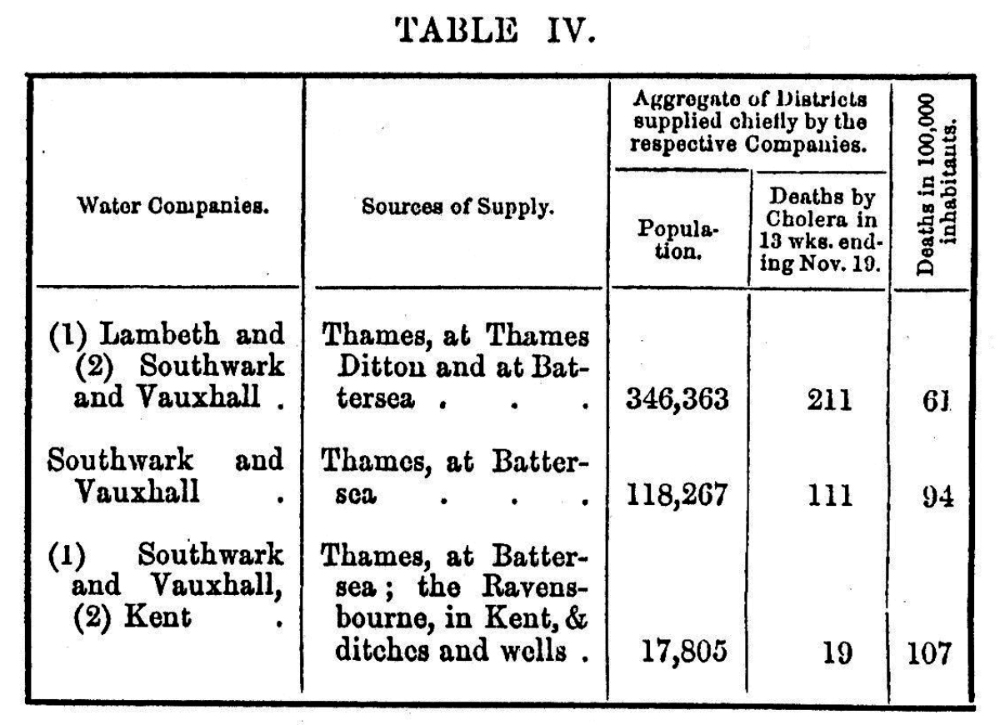

The Registrar General published the returns of the water supply, which he had obtained from the District Registrars, down to 14th October, in a table which is subjoined. As the whole of the south districts of London were included in the inquiry of the Registrar General, the deaths in the Greenwich and Lewisham districts, which are supplied by the Kent Water Company, and did not enter into my inquiry, are included in the table, but they do not in the least affect the numbers connected with the other companies.

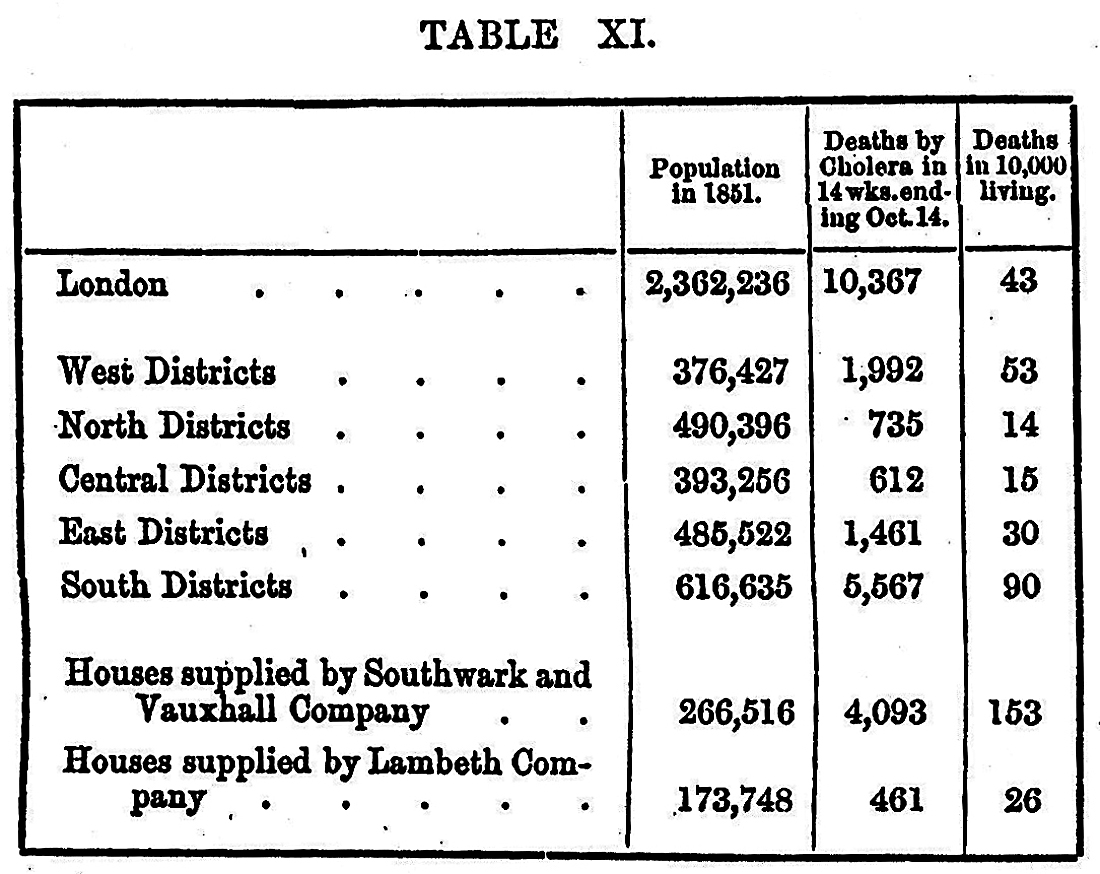

Now 2,353 deaths in 40,046 houses, the number supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, are 573 deaths to each 10,000 houses; and 302 deaths to 26,107, the number of houses supplied by the Lambeth Company, are 115 deaths to each 10,000 houses; consequently, in the second seven weeks of the epidemic, the population supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company continued to suffer nearly five times the mortality of that supplied with water by the Lambeth Company. If the 795 deaths in which the water supply was not ascertained be distributed equally over the other sources of supply in the above table (No. X), the deaths in houses supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company would be 2,830, and in houses supplied by the Lambeth Company would be 363. By adding the number of deaths which occurred in the first seven weeks of the epidemic, we get the numbers in the subjoined table (No. XI), where the population of the houses supplied by the two water companies is that estimated by the Registrar General.[4]

We see by the above table that the houses supplied with water from Thames Ditton, by the Lambeth Company, continued throughout the epidemic to enjoy an immunity from cholera, not only greater than London at large, but greater than every group of districts, except the north and central groups.

COMPARISON OF THE MORTALITY OF 1849 AND 1854, IN DISTRICTS SUPPLIED BY THE ABOVE-MENTIONED COMPANIES

In the next table (No. XII), the mortality from cholera in 1849 is shown side by side with that of 1854, in the various sub-districts to which the supply of the two water companies with which we are particularly interested extends. The mortality of 1854 is down to October 21, and is extracted from a table published in the "Weekly Return of Births and Deaths" of October 28; that of 1849 is from the "Report on Cholera" by Dr. William Farr, previously quoted. The sub-districts are arranged in three groups as before, the first group being supplied only by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, the second group by this Company and the Lambeth, and the third group by the Lambeth Company only. It is necessary to observe, however, that the supply of the Lambeth Company has been extended to Streatham, Norwood, and Sydenham since 1849, in which year these places were not supplied by any water company. The situation and extent of the various sub-districts are shown, together with the nature of the water supply, in Map II, which accompanies this work.

The table exhibits an increase of mortality in 1854 as compared with 1849, in the sub-districts supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company only, whilst there is a considerable diminution of mortality in the sub-districts partly supplied by the Lambeth Company. In certain sub-districts, where I know that the supply of the Lambeth Water Company is more general than elsewhere, as Christchurch, London Road, Waterloo Road 1st, and Lambeth Church 1st, the decrease of mortality in 1854 as compared with 1849 is greatest, as might be expected.

Waterloo Road 1st, which suffered but little from cholera in the present year, is chiefly composed of very dirty narrow streets, in the neighborhood of Cornwall Road and the New Cut, inhabited by very poor people; and Lambeth Church 1st, which suffered still less, contains a number of skinyards and other factories, between Lambeth Palace and Vauxhall Bridge, which have often been inveighed against as promoting the cholera. The high mortality of the Streatham district in 1849 was caused by the outbreak of cholera in Drouett's Asylum for pauper children, previously mentioned.

EFFECT OF THE WATER SUPPLY ON MORTALITY FROM CHOLERA AMONGST THE INMATES OF WORKHOUSES AND PRISONS

Whilst making inquiries in the south districts of London, I learned some circumstances with respect to the workhouses which deserve to be noticed. In Newington Workhouse, containing 650 inmates, and supplied with the water from Thames Ditton, there had been but two deaths from cholera amongst the inmates down to 21st September, when the epidemic had already greatly declined. In Lambeth Workhouse, containing, if I remember rightly, nearly 1,000 inmates, and supplied with the same water, there had been but one death amongst the inmates when I was there in the first week of September. In St. Saviour's workhouse, which is situated in the parish of Christchurch, and is supplied with water by the Lambeth Company, no inmate died of cholera before I called in the first week of September. On the other hand, in the workhouse of St. George, Southwark, supplied with the water of the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, six inmates died out of about 600 before the 26th August, when the epidemic had only run one-third of its course. The mortality was also high amongst the inmates of St. Olave's Workhouse, supplied with water by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, but I do not know the number who died. I trust, however, that the Registrar General, in giving an account of the recent epidemic, will make a return of the deaths amongst the inmates of the various workhouses and other institutions on the south side of the Thames, together with the water supply of the buildings. Bethlehem Hospital, the Queen's Prison, Horsemonger Lane Gaol, and some other institutions, having deep wells on the premises, scarcely suffered at all from cholera in 1849, and there was no death in any of them during the part of the recent epidemic to which my inquiry extended.

On the north side of the Thames the mortality during the recent epidemic seems to have been influenced more by the relative crowding and want of cleanly habits of the people, and by the accidental contamination of the pumpwells, than by the supply of the water companies. The water of the New River Company could have no share in the propagation of cholera, as I explained when treating of the epidemic of 1849; and the extensive districts supplied by this company have been very slightly visited by the disease, except in certain spots which were influenced by the causes above mentioned. The water of the East London Company is also free from the contents of sewers, unless it be those from the neighborhood of Upper Clapton, where there has been very little cholera. The districts supplied by this company have been lightly visited, except such as lie near the Thames, and are inhabited by mariners, coal and ballast-heavers, and others, who are employed on the river. Even Bethnal Green and Spitalfields, so notorious for their poverty and squalor, have suffered a mortality much below the average of the metropolis. The Grand Junction Company obtain their supply at Brentford, within the reach of the tide and near a large population, but they detain the water in large reservoirs, and their officers tell me they filter it; at all events, they supply it in as pure a state as that of the Lambeth Company obtained at Thames Ditton and their districts have suffered very little from cholera except at the spot where the irruption occurred from the contamination of the pumpwell in Broad Street, Golden Square. The West Middlesex Company obtaining their supply from the Thames at Hammersmith, have also very large reservoirs, and the districts they supply have suffered but little from cholera, except the Kensington brick fields, Starch Green, and certain other spots, crowded with poor people, chiefly Irish.

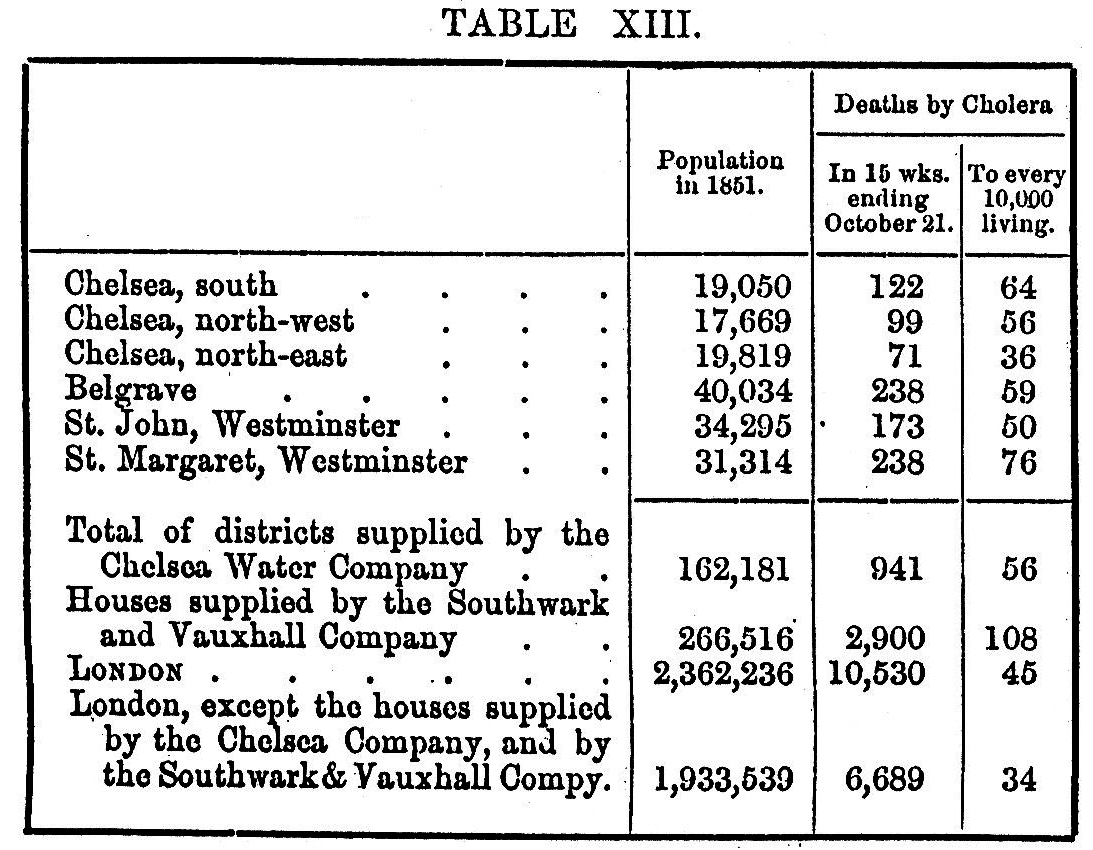

CHOLERA IN THE DISTRICT OF THE CHELSEA WATER COMPANY

The districts supplied by the Chelsea Company have suffered a much greater mortality, during the recent epidemic, than the average of the whole metropolis, as the subjoined table (No. XIII) shows.

But the mortality in these districts is only half as great as in the houses supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company, who obtain their supply from the Thames just opposite the spot where the Chelsea Company obtain theirs. The latter company, however, by detaining the water in their reservoirs, and by filtering it, are enabled to distribute it in a state of comparative purity; but I had ample opportunities of observing, in August and September last, that this was far from being the state of the water supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall Company. Many of the people receiving this latter supply were in the habit of tying a piece of linen or some other fabric over the tap by which the water entered the butt or cistern, and in two hours, as the water came in, about a tablespoon of dirt was collected, all in motion with a variety of water insects, whilst the strained water was far from being clear. The contents of the strainer were shown to me in scores of instances. I do not, of course, attribute the cholera either to the insects or the visible dirt; but it is extremely probable that the measures adopted by the Chelsea Company to free the water from these repulsive ingredients, either separated or caused the destruction of the morbid matter of cholera. It is very likely that the detention of the water in the company's reservoirs permitted the decomposition of the cholera poison, and was more beneficial than the filtering, for the following reasons. The water used in Millbank Prison, obtained from the Thames at Millbank, was filtered through sand and charcoal till it looked as clear as that of the Chelsea Company; yet, in every epidemic, the inmates of this prison suffered much more from cholera than the inhabitants of the neighboring streets and those of Tothill Fields Prison, supplied by that company.[5] In the early part of August last, the use of the Thames water was entirely discontinued in Millbank Prison, and water from the Artesian well in Trafalgar Square was used instead, on the recommendation of Dr. Baly, the physician to the prison. In three or four days after this change, the cholera, which was prevailing to an alarming extent, entirely ceased.

EFFECT OF DRY WEATHER TO INCREASE THE IMPURITY OF THE THAMES