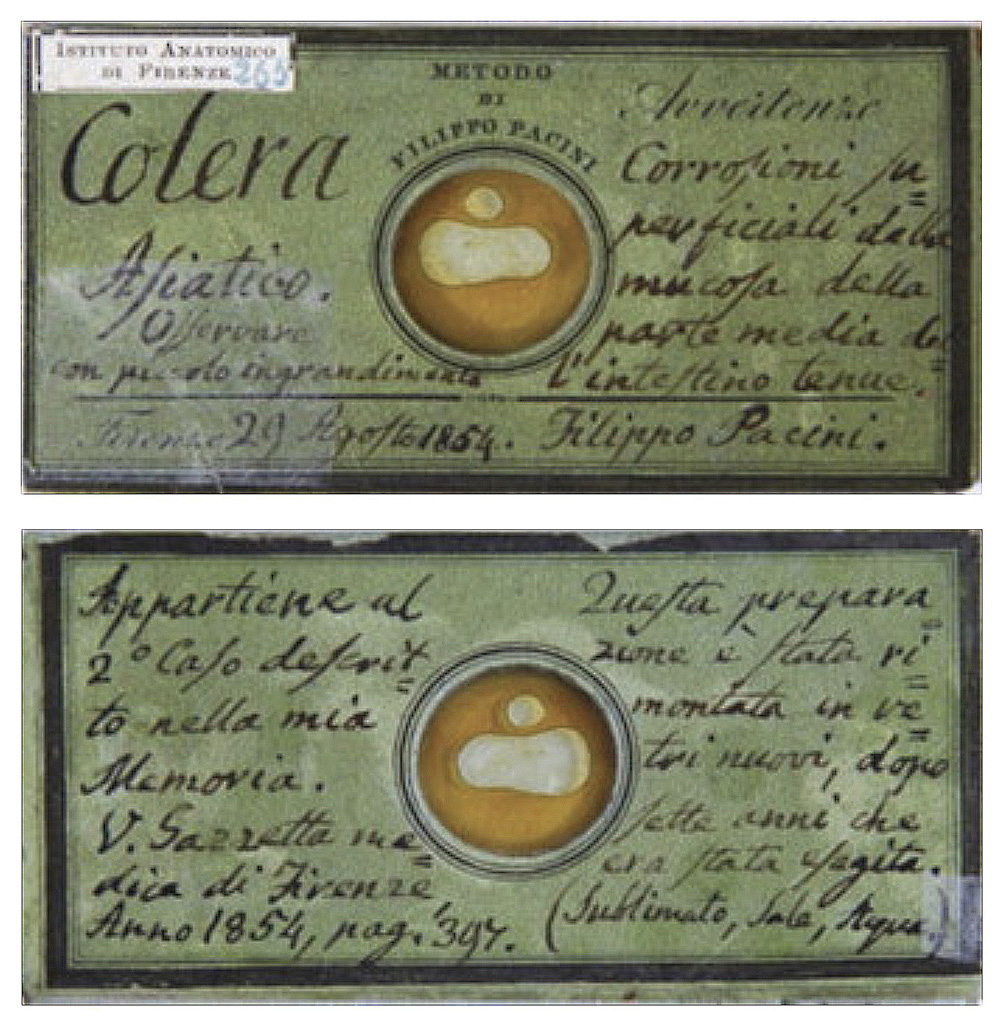

On August 29, 1854, Italian microscopist Filippo Pacini (1812-1883) looked through his powerful gifted microscope at a previously unknown organism, Vibrio cholerae. Later that year, he published his findings in Gazzetta Medica Italiana: Toscana, an Italian medical journal in the Tuscany region of Italy. The translated title of the 1854 article was Microscopical observations and pathological deductions on Asiatic cholera.

In 1965, the International Committee on Nomenclature officially adopted the formal name "Vibrio cholerae Pacini 1854," honoring Filippo Pacini.

His publication had not been noticed by John Snow prior to his 1858 death, nor by German microbiologist Robert Koch in January 1884, who identified and isolated the bacterium in pure culture while working in Egypt and India. Koch published his findings in Deutsche medizinische Wochenscrift (German Medical Weekly) in March 1884, gaining worldwide attention.

Minor Conflict with Arthur Hill Hassall

Dr. Arthur Hill Hazzal was the prominent British microscopist who had worked with John Snow in the past, and was actively involved with sanitary reform during the 1854-55 cholera epidemic in London. In his 1893 biography, Hassell offered a statement, reflecting on his earlier work with microscopic samples from hospitalized cholera patients.

With hindsight in 1893 when much was known about Vibrio cholerae, Hassall opined "Some of the bacilli seen [by me], no doubt belonged to more than one species, but from the characteristics exhibited and which are fairly represented with Koch's description, there is not the smallest doubt that the cholera bacillus was present [he termed them "vibriones"] in the [hospital] discharges in nearly every case and was first seen by me during the Cholera epidemic of 1854, now nearly 40 years since."

Back in the 1850, Hassall was not highlighting the link between water quality and cholera outbreaks, Instead, he was more focused on promoting water reform and improving public health practices. Unlike Pacini, he did not clearly state that the vibrones he saw in 1854 were related to cholera, either in theory or in practice.

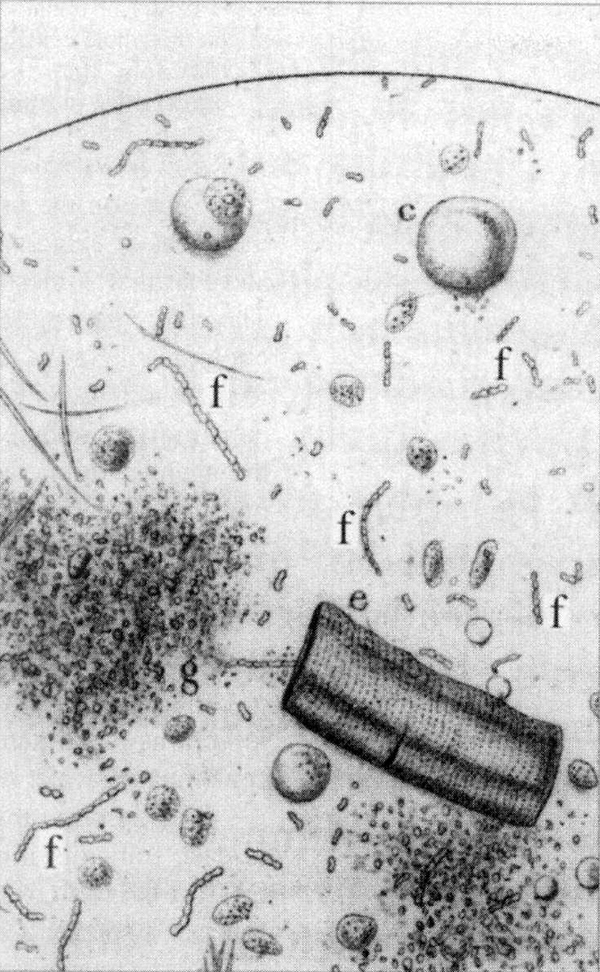

Shown at right is a sample of rice-water evauations from a hospitalized cholera patient created and viewed by microscopist Hassall. The vibriones are labelled f

During the late 1800s , many credited Robert Koch (1843-1910) with the seminal discovery of the cholera organism, not having heard of Filippo Pacini. Hence the shift from the miasma theory to the germ theory in England and Wales simmered until Koch's publication in 1884, and even then was slow to change.

Pacini maintained slide notes of his 1854 Vibrio cholerae discovery (see below), as he regularly did during all of his microscopic research. In this instance, he was examining the intestinal mucosa of patients who had died from cholera. utilizing special histological techniques on specimens collected immediately following autopsies. He saw countless numbers of comma-shaped bacteria, which he described as "vibrions," and observed disruptions in the intestinal mucosa, assumed to impair fluid reabsorption, leading to severe diarrhea and vomiting, followed by dehydration and death. These were the characteristic symptoms of what was then known as "Asiatic cholera." Note: he was the first to identify Vibrio cholerae, but not the first to culture Vibrio cholerae and demonstrate its role in causing cholera disease. That was left to Robert Koch in 1884.]

Source: Vibrio cholerae slide (front and back) by Filippo Pacini, 29 August 1854, University of Florence,

Museum of Natural History (Biomedical Section), Florence, Italy.

PACINI'S EARLY YEARS

Filippo Pacini (1812-83) was born in Pistoia, Italy on May 25, 1812. His father was a cobbler of humble means, who nevertheless provided his family with a strict religious education. From early on, Pacini's parents wanted him to become a bishop and be committed to religious studies.

At age 28 he abandoned his ecclesiastical career and turned to medicine. He accepted a scholarship in 1830 to the Scuola Medica Pistoia, a medical school founded in 1666 in Pistoia. He eventually became a physician and experienced dissector, and specialized in the use of the microscope. In 1849 at age 37, he became chair of General and Topographic Anatomy at the University of Florence, where he remained for the duration of his career.

PACINIAN CORPUSCLES

While still in medical school, Pacini observed in his anatomy course some small ovoidal bodies attached to various nerves. They were hardly visible to the naked eye, but nevertheless caught his attention. He used his meager savings to purchase a microscope and subsequently discovered and described "Pacinian corpuscles" -- encapsulated nerve endings widely distributed in the human body. Later they were found to be sensitive to pressure and to vibrations up to 400 cycles per second. Pacini first mentioned the corpuscles at a scientific meeting in Florence in 1835. By 1844, his work became widely recognized in Germany and elsewhere, and the corpuscles were named for him. At the same time, Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany donated a more powerful microscope to the University of Florence for Pacini's use (see brass image above). This helped with his discovery of the cholera organisms.

PACINI'S LATER YEARS

Pacini further developed his ideas on cholera in a series of publications in 1865 (seven years after the death of John Snow), 1866, 1871, 1876 and 1880, all in Italian. He correctly described the disease as a massive loss of fluid and electrolytes due to the local action of the vibrio on the intestinal mucosa, and recommended in extreme cases the intravenous injection of 10 grams sodium chloride in a liter of water -- later found to be very effective.

As a supporter of the germ theory, Pacini insisted that cholera was contagious. Yet similar to debate throughout Europe, his ideas were contradicted by influential Italian physicians who believed in the miasmatic theory. Even after his death in 1883, Pacini's cholera data were ignored by the broader scientific community.

Like John Snow, Pacini never married. For a long time he took care of his two sisters who were both seriously ill. He died very poor on July 9, 1883, having spent all of his money on his scientific investigations and medical care for his sisters. His family care-giving and increasing poverty may have limited his ability to further promote or disseminate his cholera findings.

THE FAME OF ROBERT KOCH

As one of the main founders of the science of bacteriology, Robert Koch (1843-1910) enjoyed worldwide fame, including acknowledgement of his discoveries in 1876-77 of the anthrax bacillus (Bacillus anthracis), in 1882 of the tubercle bacterium that caused tuberculosis ( Mycobacterium tuberculosis) and in 1884 the cholera bacillus (Vibrio cholerae).

Koch, like most of the scientific community, was unaware of Pacini's work at the University of Florence. Yet both independently came to a similar conclusion. Since Koch's findings eventually became accepted by his scientific peers, and were widely know in the popular press, he became the acknowledged discoverer of the cholera organism.

REDISCOVERY OF CHOLERA ORGANISM

During 1883, cholera was epidemic in Egypt. Koch traveled with a group of German colleagues from Berlin to Alexandria, Egypt in August, 1883. Following necropsies, they found a bacillus in the intestinal mucosa in persons who died of cholera, but not of other diseases. He reasoned that the bacillus was related to the cholera process, but was not sure if it was causal or consequential.

He stipulated that the time sequence could only be resolved by isolating the organism, growing it in pure culture, and reproducing a similar disease in animals. He was not able to obtain such a pure culture, but did try to infect animals with choleraic material. None became infected. His thoughts and early findings were sent in a dispatch to the German government and shared with the German press.

Late in 1883, Koch requested authorization for his team to sail to Calcutta, India to continue their work. The epidemic had subsided in Egypt but was still very active in India.