BIRTH HOME

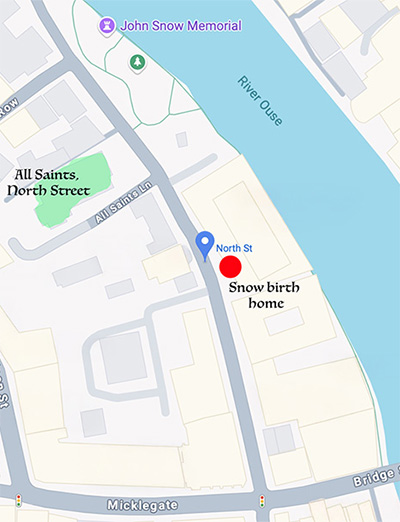

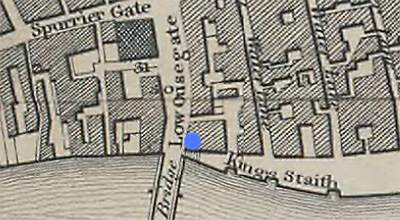

John Snow was born on March 15, 1813 in a house on North Street in York, England (at right), the first of nine children of William Snow (1783-1846) and Frances Snow (Askham) (1789-1860). His parents had married on May 24, 1812 using the address of Frances's parents in Huntington, a farming parish just north of York. John Snow's father was 29 years old and his mother was 23. Ten months later, they had John Snow, their first born.

The family lived on North Street, alongside the River Ouse on the back side of their home which, prior to the advent of the railways in the late 1830s, was one of the main river thoroughfares for the dispatch of heavy goods and materials to and from York.

His neighborhood in North Street was among the poorer regions of York, being always at risk of flooding from the Ouse River through his back door, and considered one of the worst drained areas in the city.

At the time of Snow's birth, and during most of his early childhood, his father worked as a laborer in a nearby coal yard, one of many poorer, unskilled, manual workers in the city.

Barges on the River Ouse brought coal to the yard, situated adjacent to the family home.

In current York, Snow's birth-home is now occupied by the Radisson Hotel, with plaque at side.

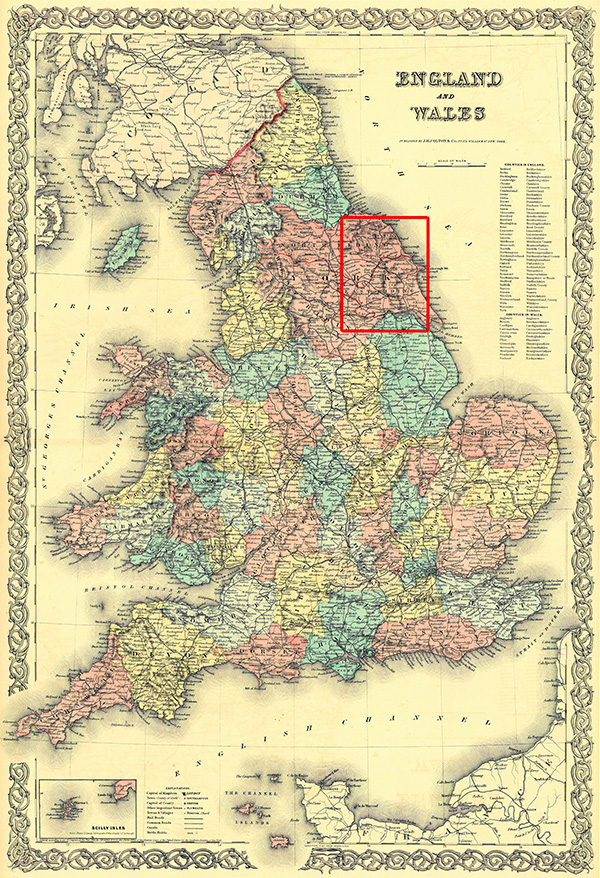

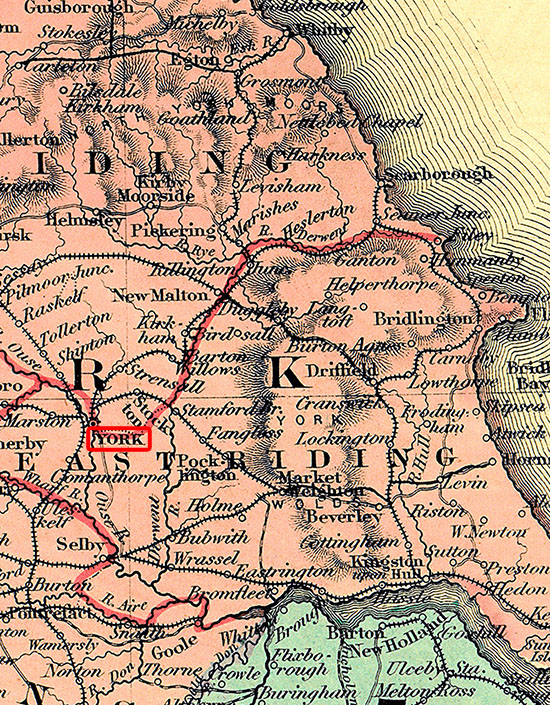

In 1813, the population of York was likely fewer than 17,000, surrounded by Yorkshire County in northern England. Since 1396 the City of York has been a self-governing entity, different from other English cities.

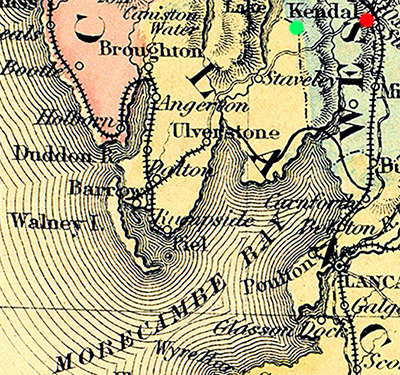

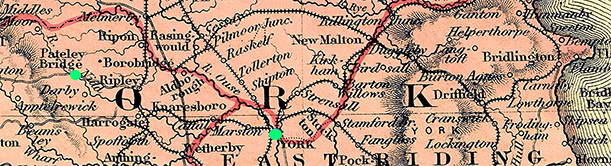

The 1856 map of England Wales at left shows where York is located (outlined by a red rectangle), well north of London. An enlargement of this section of the map is seen below, showing York in the middle left.

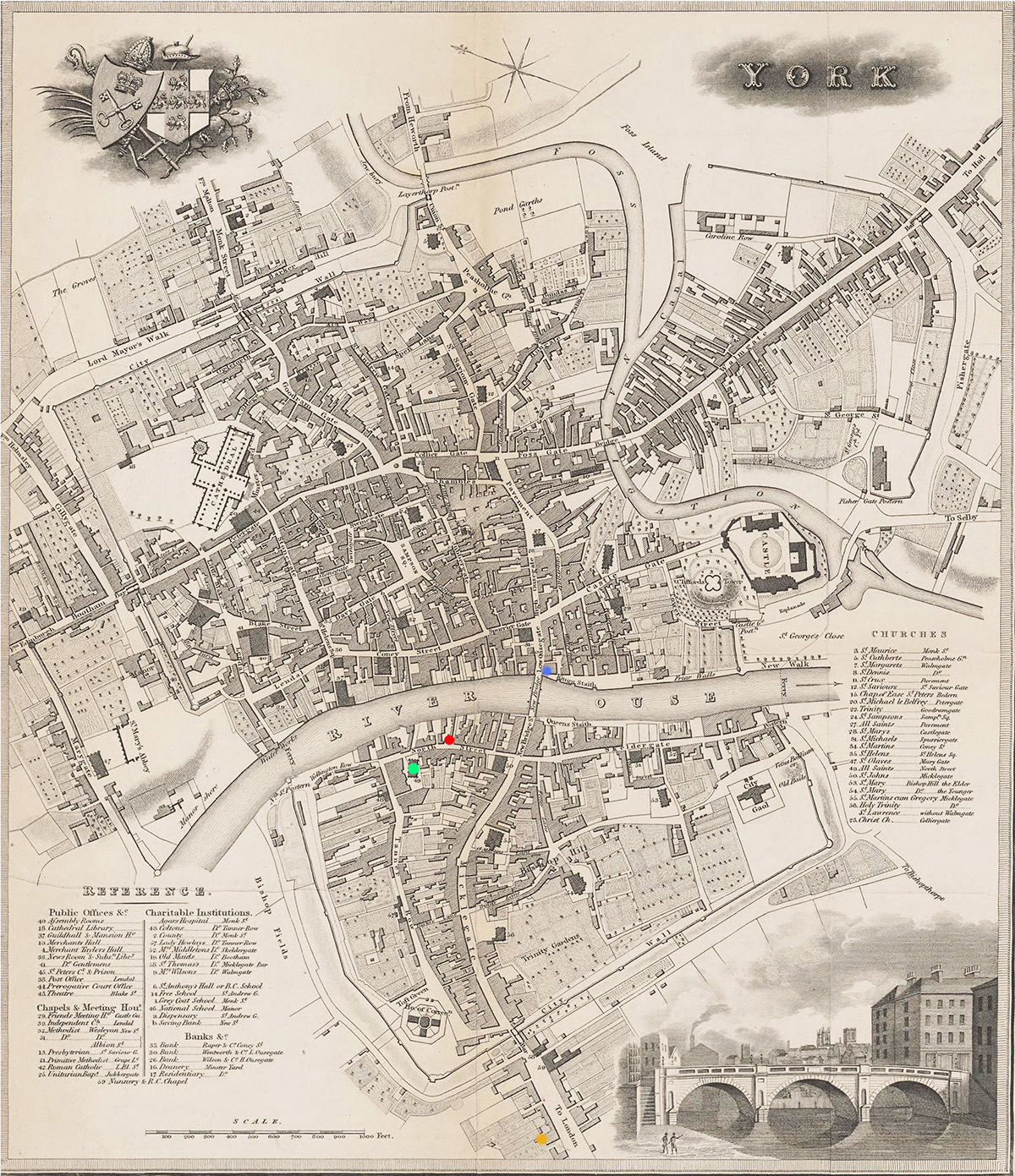

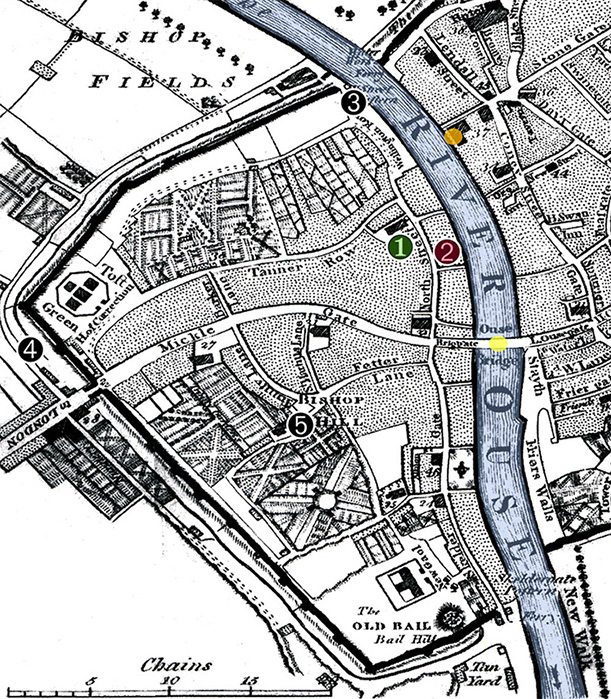

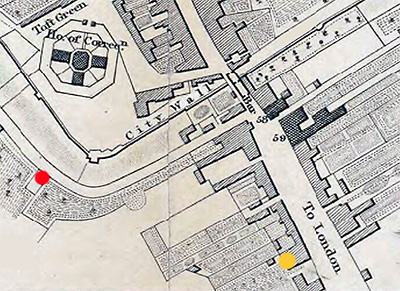

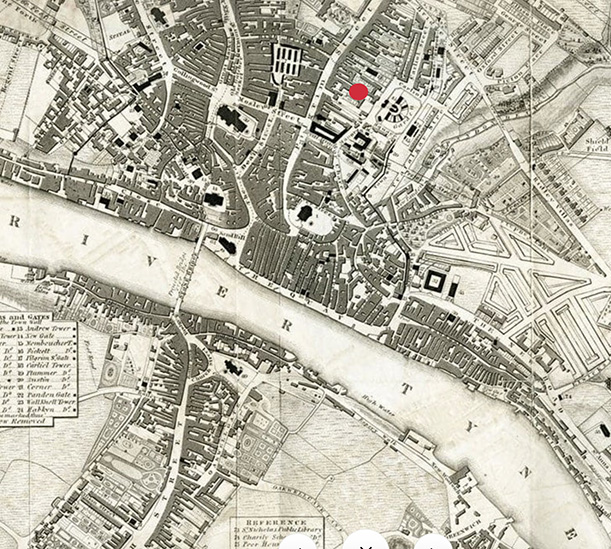

Cartographer Alfred Smith in 1822 created a new map of the city of York, shown below, then populated by about 30,000 people. At the time, John Snow was nine years old. The Snow home is shown on North Street (red dot), a short ways from the Anglican church of All Saints North Street that the family attended (green dot). The full map also shows the future locations of the Commercial Temperance Hotel just north of the River Ouse owned by Snow's brother William (blue dot) and the school for young ladies owned by his sisters Mary and Hannah in "The Mount" area just south of the city wall off Micklegate (orange dot).

The enlarged section of the 1822 map just below the original map focuses on the three homes where young John Snow lived in York during the first 14 years of his life and the school that he attended.

Source: Smith, Alfred. published in Edward Baines' History, Directory and Gazetteer of the county of York, Leeds,1822.

For the first 10 years of John Snow's life, the family lived by a coal yard, where his father worked. The family moved to Wellington Road in the same neighborhood when John Snow was 10 years old, and then even further away to Queen Street when he was 12 years old, still within walking distance of his school. At that time, the Snow family had their last two children and appeared to settle down for a while. John Snow was educated for eight years at Dodsworth School on Bishop Hill (gold dot in map below). The school was adjacent to the St Mary's parish church, Bishop Hill (at right).

By age 14, John Snow had completed his early education. Thereafter, he left home to start his three medical apprenticeships.

SURROUNDINGS AT BIRTH

William Hargrove in 1818 published a map of Micklegate Ward, the area in York where John Snow was born and spent his early years. Two landmarks along the River Ouse are shown as an orange dot (The Guild Hall) and a yellow dot (Ouse Bridge). The numbered sites are:

1) All Saints North Street church is shown in green (#1).

2) Snow's birth-home is presented in red (#2)

3) In 1823 when John Snow was 10, his family moved to Wellington Row (#3).

4) Two years later in 1825 when John Snow was 12, the family again moved, but this time to Queen Street (#4) where Snow's father accumulated land and rental properties.

5) Dodsworth School in Bishop Hill (#5), where John Snow likely received his early education from ages 6 to 14 years.

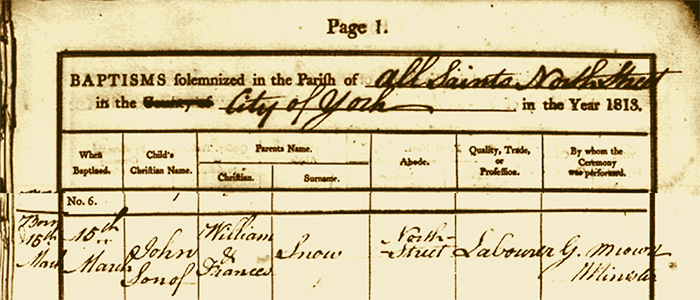

Religion was a central part of the Snow family life. They attended York's Church of All Saints, North Street (at left, #1), and the children were all baptized there, including John Snow.

His baptismal entry on the same day he was born (presented below) shows him being born on 15th March as John, son of William and Frances Snow of North Street. His father was listed as a laborer. The baptism was performed by Minister G. Brown, Rector of the Church from 1789 to 1817.

Towards the end of life, both parents would request being buried at the Church of All Saints, North Street , even though they had since moved away from York.

Usually the children of poor families left home to earn their own livings as soon as possible. Snow's parents, however, seem to have been determined to give their offspring whatever educational opportunities availed in York so as to better themselves.

The hexagonal wooden pulpit in the Church of All Saints, North Street dates back to 1675. Around the top of the pulpit is a text from St Paul's epistle to the Romans: "And how shall they preach except they be sent," and on each side of the pulpit is a painting of a female figure representing a virtue.

Source: Photo by Stefan Kusinski, Churchcrawling - church art, architecture and history, May 19, 2019.

Another view of the interior of the church, with the ancient pulpit at the far left.

Source: Photo by David Striker, 2020.

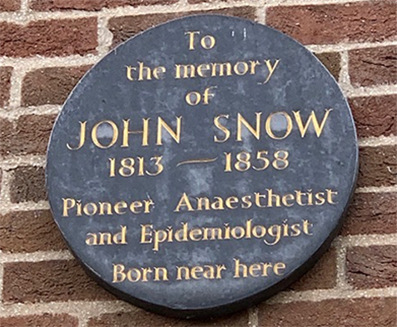

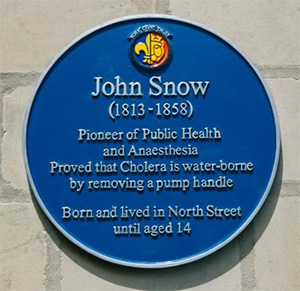

HONOR AT BIRTH SITE

In 2017, John Snow was honored near his birth home in the North Street Gardens of the city of York, with an old-style water pump, separated handle and a written plaque.

As a local reporter noted at the event: "It looks for all the world like a Victorian water pump, minus its pump handle (which is lying on the ground nearby). And that is, in fact, precisely what it is."

The plaque briefly tells of his achievements and his childhood link to his family home on North Street.

A larger sign tells of the Memorial and John Snow's life, beginning in York, extending to London, and eventually to influencing the world.

The John Snow Memorial in York

The March 15, 2017 memorial in North Street Gardens reads: Dr. John Snow (1813-1858) was a Victorian physician, a pioneer in the field of anaesthesia and epidemiology, famed for his tracing of the source of a cholera outbreak in London's Soho and confirming that it is a waterborne disease.

John Snow was born on this York street on 15 March 1813 and was baptised in All Saints' Church across the road. His father was a labourer in a local coal-yard.

Aged just 14, John was apprenticed to William Hardcastle, a Newcastle-upon-Tyne surgeon-apothecary who also grew up in this area of York. In 1836, aged 23, he moved to London to complete his medical training.

John became interested in the new anaesthetic agents Ether and Chloroform, devising pumps to ensure accurate dosing and safer surgery. He administered Chloroform to Queen Victoria during the births of Prince Leopold in 1853 and Princess Beatrice in 1857.

Following his early experience of cholera in Newcastle and the 1849 London epidemic, he published 'On the mode of Communication of Cholera', suggesting that cholera was water-borne and caused by contamination of water by sewage. He advocated washing hands before handling food.

During the 1854 Soho epidemic, he plotted the cases on a street map and proved the link to the Broad Street pump. Despite oppostion, the council removed the handle and the epidemic rapidly declined.

Considered the father of epidemiology, the study of the origins and spread of disease, John Snow died of a stroke on 16 June 1858 and is buried in the Brompton cemetery, London.

BROTHERS AND SISTERS

John Snow had five brothers and three sisters, born every two years. His was the first birth in 1813.

William (1815-86) was a tailor, married with 5 children, and owned and operated the Commercial Temperance Hotel at 3, Low Ousegate in the central part of York (blue dot on 1822 map). His hotel was on the other side of the River Ouse bridge from the home on North Street where he spent his first 8 years, and a short walk from the railway station and the York Castle, convenient for teetotaling lodgers.

Charles (1817- abt 1858) likely worked for a while at home with his father and perhaps with his brother William at the temperance hotel in York. He later emigrated to Australia and died there around 1858 but prior to John Snow's death, estimated since he was the only living sibling left out of John Snow's will following his death on June 16, 1858.

Robert (1819-85/86) was a mining engineer who became Manager of Carforth Colliery (a coal mine at right) near Leeds. He was married and had at least four children.

Thomas (1821-93) at first was a teacher and then at age 33 entered the clergy of the Church of England, eventually becoming vicar in 1874 of the All Saints Church in Underbarrow (green dot on 1856 map) in the County of Westmorland, situated in the north of England. Kendal (red dot) was a principal town in Westmorland county. The village of Underbarrow lies north of Morecambe Bay, known at the time for its quicksands and treacherous, fast-moving tides, not for recreation.

Thomas Snow remained there until his death. He had married, had two sons, was widowed and then married again, having a third son. Like his eldest brother John, Thomas was a strong supporter of the temperance movement and was a teetotaller. He remained close to his brother John, being at his side when he died in 1858. Later he registered John Snow's death in London.

Mary (1823-1911) and Hannah (1825-1904) ran a school for young ladies at "The Mount" in York (orange dot on 1822 map), located south of the city wall on the road towards London. They were teachers and administrators before retiring, then moved to Harrowgate, North Yorkshire. Like their father, they had invested in various properties and did well financially, but never married.

Nearby (red dot) was the Queen Street home where the Snow family had moved when Mary was aged 2 and Hannah was just born. Later the family moved from York to Rawcliffe when the girls were aged 18 and 16, respectively.

Sarah (1827-91), the youngest daughter lived in York until she was aged 14, then moved to Rawcliffe. She married a farmer, perhaps from the small, farming-dependent village of Rawcliffe, and bore six children.

George (1828-30), like many children of this era, died young. At the time of his birth, their last, his mother Frances was aged 39 and his father William was aged 45.

EARLY EDUCATION

When he was 6 years old, John Snow attended a private school in York, the Dodsworth School at Bishop Hill, named after York ironmonger John Dodsworth, intending to educate boys of poor families. The school was heavily subsidized, endowed with Dodsworth's stock holdings in his will of 1811. John Snow's name was 1 of 3 submitted by his church All Saints, North Street, where the Snow family were church members. Snow's Dodsworth School had about twenty funded boys between ages six and fourteen, emphasizing reading, writing, arithmetic and the Scriptures. John Snow was an industrious pupil and mathematics and natural history were his favorite subjects. He also studied Latin and Greek.

While it is not clear how Snow's father, a poor laborer, was able to educate all of his children, some historians suggest that money to assist John Snow and the other children with their education came through John's mother, Frances. She was the sister of Charles Empson (1794-1861), an affluent and well-traveled man who later was a leading figure in Bath society (Bath is a small city about 200 miles south of York and 100 miles west of London). What suggests otherwise, at least for John Snow, is Charles Empson's long journey, which took him to South America for three years (i.e., 1824-27) when John Snow was 11 years old. At that time, Empson was not yet a wealthy man. Later, however, Charles Empson probably helped finance the education of some of the younger Snow children, aspects of John Snow's London education and the start of his medical practice.

JOHN SNOW'S FATHER

More likely, John Snow's early education was supplemented by his industrious father William Snow. His parents married on May 24, 1812 at the Church of All Saints, North Street. During that time, the father was listed as a laborer with no resources other than a clever mind and ambitious nature.

By 1819 (when John Snow was age 6 and ready for school), his father had changed his occupation from laborer in a coal yard to carman, or driver of horse-drawn vehicles, delivering goods that arrived by the Ouse river, or possibly distributing supplies to the various warehouses in the area. Then in 1823, the family moved to Wellington Row, about a block down from Snow's birth house. He saved his money and in 1825 bought a house in Queen Street and then during the 1830s when Snow was away in his first apprenticeship, purchased four more houses and a yard, also in Queen Street. The houses were rented to tenants, bringing additional income to the family.

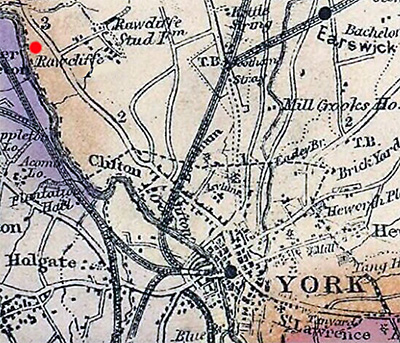

In 1832 when John Snow was 19 and serving his medical apprenticeships, his father's occupation was listed as farmer, possibly because he was tilling small plots of land on Queen Street. He remained in Queen Street until 1841 (John Snow was 28 and already a doctor), when he moved with his wife from York to Rawcliffe (red dot on Bacon's 1875 map), a rural agricultural village about 3 miles northwest on the banks of the River Ouse, and purchased a farm.

By then William and Frances had eight living children, ranging in age from 14 to 28 years. Five years later in 1846, John Snow's father died at age 63. His mother outlived her husband by 14 years and John Snow and his brother Charles in Australia by two years, meeting her death in 1860 at age 71.

Snow's parents left a remarkable legacy for a couple that started poor, but eventually experienced success via their own lives and that of their children. Such upward social mobility, including having a son who administered chloroform at two births of Queen Victoria, was extremely rare in nineteenth century British society.

FIRST APPRENTICESHIP

Before going off to London for his formal medical education, John Snow had three apprenticeships with medical practitioners. During early to mid-1800s, only a few organizations were empowered to grant licenses for medical practice in England. Two were universities -- Oxford and Cambridge -- to which Snow had no chance of admission.

Instead he took the alternative route of being an apprentice with a licensed surgeon and apothecary (another name for a pharmacist), with the anticipation that one day he would pass the licensing test given by the medical group (Royal Colleges of Physicians and of Surgeons) and the pharmacy group (Worshipful Society of Apothecaries).

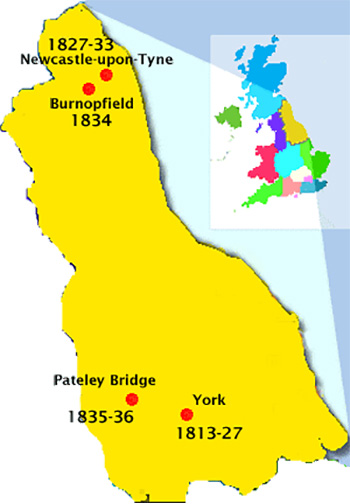

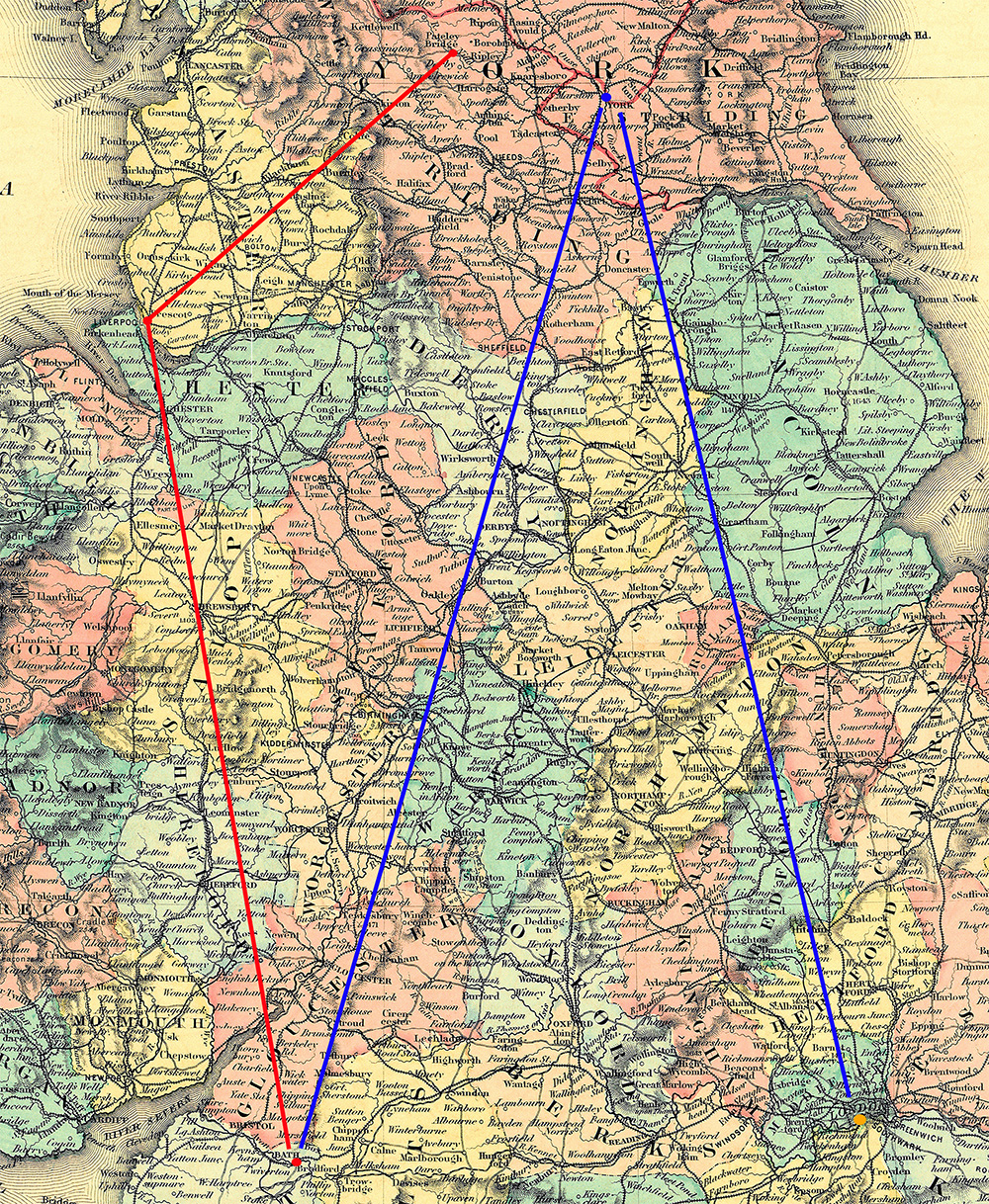

Snow's apprenticeships began in 1827 and lasted nine years. The locations and years he spent there are shown in the map at right, in a central region of England.

At the age of fourteen John finished his early education at the Dodsworth School in York, and was sent to Newcastle-upon-Tyne (see upper red dot in map). He became an apprentice on June 22, 1827 to William Hardcastle, a surgeon-apothecary (the term for what is now known as a general practitioner, but not bestowed with the title of "Dr").

John Snow's uncle, Charles Empson, was a friend and confidant of Mr. Hardcastle, listed as both witness at Hardcastle's wedding and executor of his will. Mr. Hardcastle was also the physician for the George Stephenson family. A member of the family, Robert Stephenson, was a good friend of Charles Empson. Likely these friendships lead to Snow's apprenticeship so far away from his home in York.

Mr. Hardcastle was an established practitioner of good reputation in the Newcastle-upon-Tyne area who was thirty-one years old at the outset of Snow's apprenticeship.

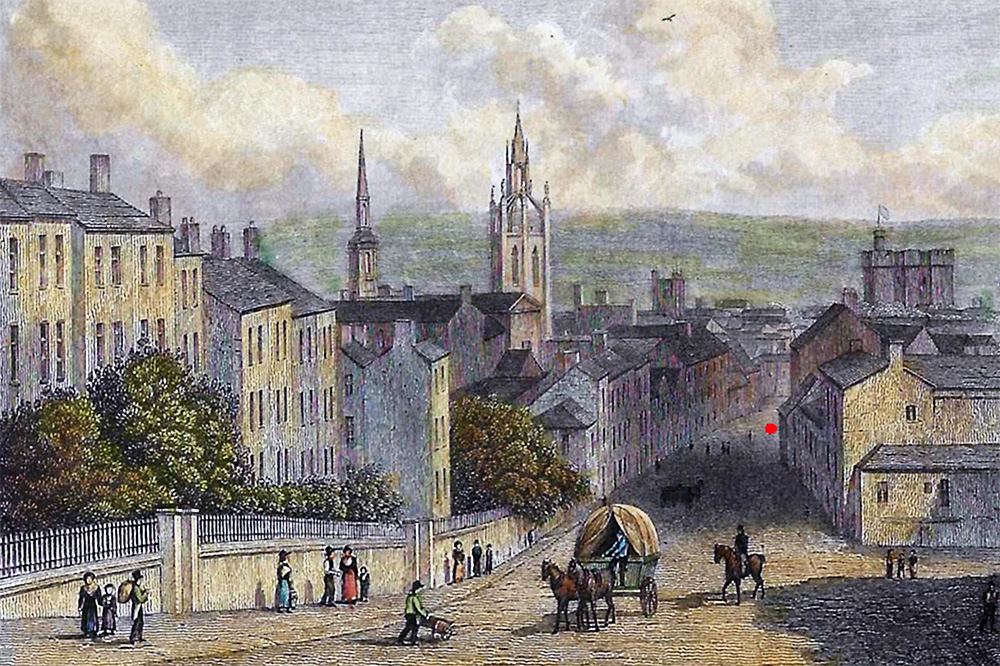

Hardcastle's practice was on Westgate Street, opposite the side gate of St. John's church (see red dot below in modification of William Westall 1830 painting).

Snow's apprenticeship in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, which lasted six years, was an important time for him. Not only did it lay the foundations of his medical training but it was also the period in which he developed interests and attitudes which were to be with him for the rest of his life.

During the third year of his apprenticeship when he was 17 years old, he became a vegetarian and remained so until age 25. Snow was a noted swimmer at this time, and apparently could swim longer against the tide of the River Tyne than any of his meat-eating colleagues (see modified Turner 1823 painting below). During the same period, he also took up the temperance cause (no alcohol), joined the ranks of the total abstinence reformers, and for many years became a powerful advocate of their principles.

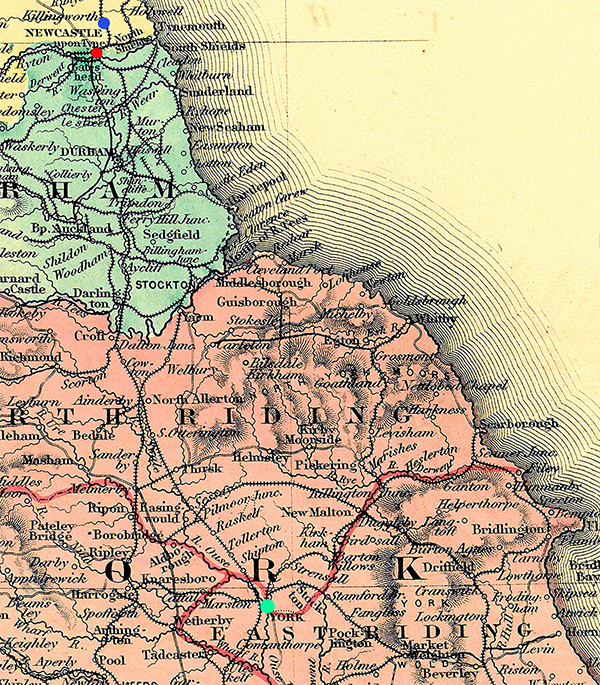

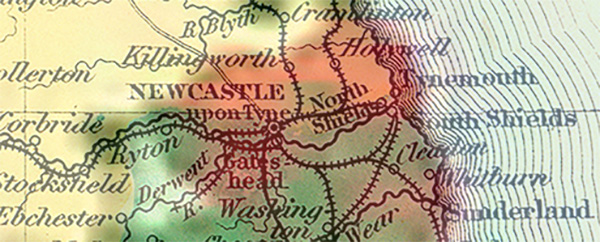

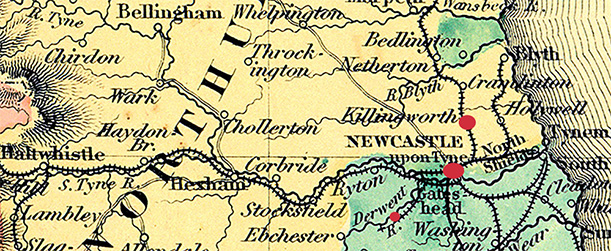

Coal Country in Killingworth

Snow first apprenticeship had taken him from York (green dot) to the urban areas of Newcastle-upon-Tyne (red dot), including the coal mines of Killingworth (blue dot). Killingworth sits in the historic county of Northumberland.

Newcastle upon Tyne during the years of Snow's local apprenticeship was a major coal-producing and exporting center. The city's location on the River Tyne and proximity to accessible coal seams made it a key location for coal shipments, especially to London. Many of Hadcastle's patients were involved with the extraction, transport, and trade of coal. While the coal fields near Newcastle were largely depleted, the mines by Killingworth north of the city, were still very active.

CHOLERA

On December 7, 1831, cholera first appeared in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, with the epidemic ending in the late summer of 1832, totaling 801 deaths. At about the same time, cholera had also spread to Killingworth, a community included in Hardcastle's practice. Hardcastle was soon appointed as a "Poor Law" medical officer to attend the disease among the poor of Killingworth. Facing a time conflict with his local practice, Hardcastle sent Snow to deal with cholera in the West Moor colliery (a coal mine together with its physical plant) in Killingworth as his unsupervised assistant.

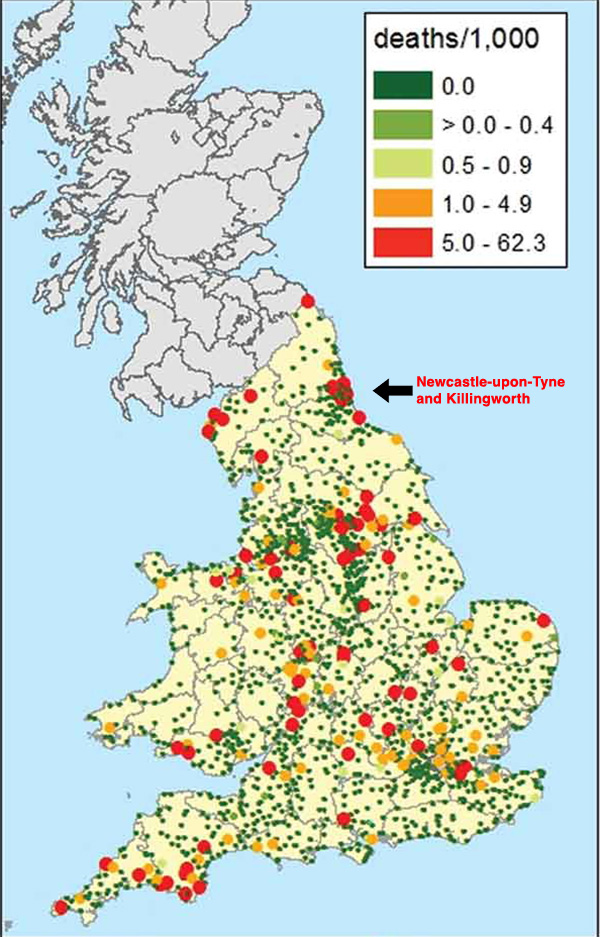

Cholera death rate, England, 1831-32 epidemic

During the nineteen century, England experienced four major cholera epidemics, starting in 1831-32 (the others took place in 1848-1849, 1853-1854, and 1866).

For 1831-32, the figure at left presents England's national cholera death rate map, with areas in red having the highest rates. By superimposeing the national death rate map over the 1856 map of the Newcastle-upon-Tyne region, including Killingworth, the local impact of cholera in the red high death rate zone is clearly discernable (see below).

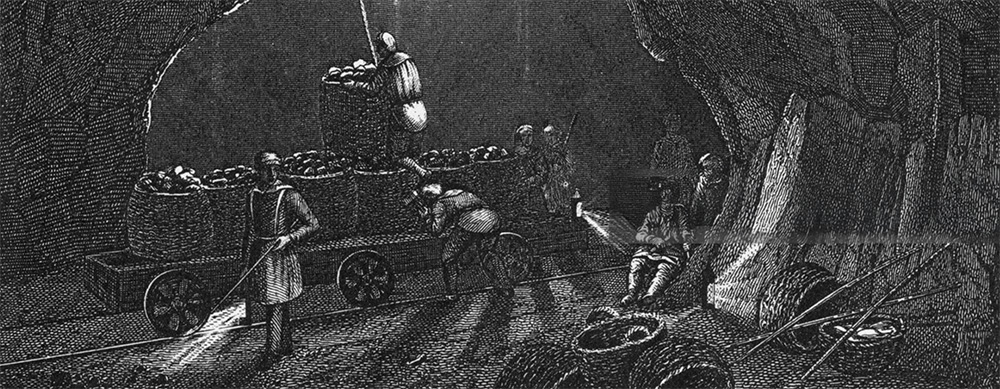

Cholera and Coal Pits

The miners and their families were victims of the cholera outbreak. This experience likely gave Snow a sense of mission, which continued in his future epidemiological investigations.

Years later Snow wrote of this time, "That the men [who work in coal pits - see below] are occasionally attacked [by cholera] whilst at work I know, from having seen them brought up from some of the coal-pits ... after having had profuse discharges from the stomach and bowels, and when fast approaching to a state of collapse."

Early Medical Education

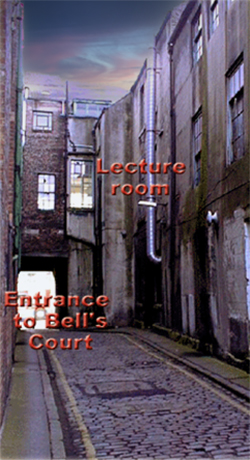

In 1832, John Snow was 19 years old and in the fifth year of his apprenticeship with William Hardcastle in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, viewed below by the river and the map at right, with the red dot showing Bell's Court, the starting location for what would eventually become the University of Newcastle-upon-Tyne School of Medicine in 1963.

In October of 1832, six local practitioners joined together in a private venture to teach medical courses for interested local students.There were eight or nine individuals who attended these initial set of lectures, presented in such areas as chemistry, surgery, anatomy and physiology. John Snow was one of those students. They gathered in the center of town in Bell's Court (see red dot at right in 1831 map).

Bells Court where the 1832 group assembled is on Pilgrim Street near the town jail built in 1823.

The lecture room was over the shop on the north side of the entrance to Bell's Court off Pilgrim Street (at left). To get to the lecture room, Snow walked into Bell's Court, turned left and climbed the stairs to the second floor (at right)

The fee for each six month lecture was 2 guineas, while the total annual cost for a full set of 12 lectures (six each half year) and infirmary attendance was 29 guineas.

If Snow attended all of the courses, he probably was either provided a scholarship based on need, his connections to William Hardcastle, or was given financial assistance from his uncle Charles Empson or Robert Stephenson, the close friend of his uncle.

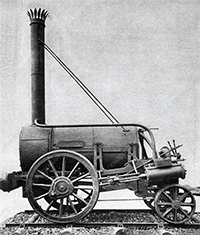

Both Empson and Stephenson were living in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, the former finding success as a seller of fine art books and the latter as an engineer and entrepreneur. Robert Stephenson, along with his father George, built high-speed locomotives (including the famous Rocket, at left) at Robert Stephenson Company on Forth Street in Newcastle- upon-Tyne. His successful and lucrative company was the world's first locomotive builder.

Two years after the Bell's Court beginning, a new start was made by the group of medical instructors, but this time with 26 students. The 1834 group of practicing doctors moved to another setting, the Barber Surgeon's Hall, which was about 200 yards south of Bells Court next to the Holy Jesus Hospital (see 1831 map to the right). This officially became the School of Medicine and Surgery in 1834 .

By then, John Snow had already relocated to Burnopfield for his second apprenticeship, but managed to periodically make the eight mile return trip to attend various lectures.

SECOND APPRENTICESHIP

In April 1833, when he was aged 20 and had completed his six years of apprenticeship with Mr. Hardcastle, John Snow went south and west to Burnopfield, a village also near Newcastle-upon-Tyne (small third red dot, 1856 map at right) and became an assistant to Mr. John Watson, a rural apothecary. His intent, most likely, was to remain an assistant for a few years, save money, before going to London for two years of medical education to become a licensed practitioner.

THIRD APPRENTICESHIP

Snow remained in Burnopfield for about a year, and then following a brief home leave, joined a medical practice in Pateley Bridge to the west of York (see green dot in map at right) for eighteen months. Unfortunately, he apparently had little in common with Burnopfield's Mr. Watson, who relied more on clinical experience rather than book learning, and considered his wages to be very low.

Snow left Burnopfield in April 1834, and returned home to York for a few months.

His father at that time was becoming a landlord, renting rooms in properties he owned in York.

When Snow went in the autumn of 1834 to Pateley Bridge, his medical mentor was Mr. Joseph Warburton, a licensed apothecary. Pateley Bridge was in a remote region with scattered settlements to the west of York. The town had a population of about 1,500, with most involved with agriculture, spinning and weaving of flax, quarrying, and lead mining. Snow may have been short of money, needing to earn enough to continue his medical education in London, or perhaps was aware of Warburton by reputation, more prominent than Watson in Burnopfield.

He lived in a large house that served as both home and surgery to Joseph Warburton, wife Harriet, and their three children. At this time Snow was a strict vegetarian, apparently puzzling Mrs. Warburton, shocking the cook, and astonishing the children. He also attended local lectures on temperance, accepted the principles of total abstinence, and took the pledge. His teetotal address, later published in the British Temperance Advocate, was delivered in 1836.

Snow viewed Warburton with great respect and friendship, later referring to him as his "old master." He remained in Pateley Bridge for about 18 months.

The Long Walk

At the end of his Pateley Bridge apprenticeship (now three in number), John Snow in the summer of 1836 took off for 4-5 weeks for a walk of about 400 miles, starting in Pateley Bridge (upper red dot), on to Liverpool (middle red dot), then on to Bath (lower red dot) to visit his uncle Charles Epson. Along the way, he spent nights at inns, pubs and village homes. Snow returned to York (blue dot) by two-day stagecoach travel in mid-June before again leaving by stagecoaches for London (orange dot) in October 1836. York did not have rail service until mid-1839, but only at a temporary location, building a permanent station within the city proper in 1841.

Source: Colton Map of England and Wales, J.H. Colton and Co., New York, 1856.

During the 1830s, walking long distances was becoming increasingly popular in England, both out of necessity for the working class and as a form of inspiration and recreation for others. Besides walking, Snow was also an excellent swimmer.

While spending his long 1836 summer back in York, he and his brother Thomas played a part in creating the York Temperance Society. Thereafter he worked to establish other local temperance societies, reflecting the depth of his feelings against alcohol.

Aside - The Temperance Movement in England during the 1830s

Aside - The Temperance Movement in England during the 1830s

In the spring of 1836 before leaving on his long walking and train trip, 23-year old John Snow had delivered a teetotal address in Pateley Bridge. His focus was on the physical evils of alcohol consumption, even in moderation, and he put forward his case for total abstinence as the only cure. While others dealt with the social consequences of drunkenness, Snow's address had a more focused medical message, believing that medical professionals had valuable insights to share on health-related matters.

While John Snow gave the teetotal address in Pateley Bridge, he did not publish it. Instead it was written and delivered by Snow but then left in a drawer somewhere. Decades later in 1888, his surviving younger brother Thomas Snow (1821-1893) edited the document and submitted it to the British Temperance Advocate for publication. By then, thirty years has passed since the death of John Snow. Hence, his younger like-minded brother Thomas was cited as the author and editor, while John Snow was clearly listed in the title as the creator and presenter.

Teetotal address of John Snow at Pateley Bridge, in the spring of 1836 (age 23),

towards the end of his third medical apprenticeship

I feel it my duty to endeavour to convince you of the physical evils sustained to your health by using intoxicating liquors even in the greatest moderation; and I leave to my colleagues the task of painting drunkenness in all its hideousness, of describing the manifold miseries and crimes it produces, and of proving to you that total abstinence is the only remedy for those evils. If I could bring you, my friends, to see these liquors in the same light as I do, you would then abstain from them without considering it an act of self-denial, or a sacrifice you were making for the benefit of society, but an act of justice to yourselves, the neglect of which would be irrational.

I shall, then, detain you a little in trying to investigate the causes that have rendered the use of these liquors so universal, so fashionable, nay, even so credible. One great cause, I believe, is an unhappy action of that noble principle in man which makes him strive to imitate whatever is above him; that thirst of progressive improvement, unpossessed of which we should remain as stationary as brutes; and which, if allowed to lie dormant, would cause us to remain for generations with as little improvement as the Chinese. When these liquors are first introduced amongst a people, they are something new, rare, and expensive; the impression therefore is, that they must be good; and before the novelty has worn off, the people have got endeared to them by all the ties of acquaintanceship. The poor man, or the man in middling circumstances, must imitate those above him as well as he can, without considering whether his acts are wise or not. The lad wants to be a man, and the child a lad; and if wine tastes sour, or ale bitter, or they make his head ache, it must be, he thinks, because he is a greenhorn. He must get more used to them, and then he will enjoy them as others do.

The great and palpable evils, too, occasioned by drinking these fluids in excess, divert our attention from the mischief done by taking them in what is called moderation. A moderate use of them does not produce all these evils; therefore moderation must be a good thing! Might we not as well say that because gambling a little with small sums does not put a man and his family to the risk of starvation, and produce all the distress and crime that gambling to excess does; therefore gambling in moderation must be a good thing! I would have you pause and consider whether there is any wholesome article of diet, which, if taken in the greatest excess, will cause such serious derangement in the economy, as fermented liquors do. I think there is none, and I would have you view with especial suspicion, a food that will make you want the more of it the more you get.

A great deal has been said, and justly too, about the destructive properties of ardent spirit, and it may all be applied with equal propriety to ale and wine. The question seems to reduce itself to this. Either wine and ale are pernicious, or ardent spirits are wholesome when mixed with water. Port, and some of the stronger kinds of wine, contain about half as much alcohol as rum and brandy: the weaker kinds not so much, and made wine, even when you tell us it has no spirit in it, contains one-fourth or one-fifth part as much. Porter contains about an eighth part, and ale about a tenth part, in addition to some hop, which is a bitter sleep-inducing plant. And this is your healthful home-brewed, which contains no drugs!

Another great cause of the credit these liquids have got is the instruction of medical men. Some medical men are so far in the wrong as to think that these drinks may safely be used in moderation. When they commence their studies they learn the names and properties of medicines, and the nature of diseases and their remedies; and generally speaking, they pay little attention to the properties of food, and other things which act on the body in its healthy state; or if they do pay attention to these things, perhaps they have already got a taste for what are called the good things of this world, and they easily chime in with opinions of many who have gone before them. The passions and appetites, my friends, have a very great share in forming one's opinions, even when one wishes to be most impartial.

And when medical men are sincerely of opinion that total abstinence from all that contains alcohol is the only plan congenial to health, they often get misunderstood. A patient asks his attendant if he may have some wine. Now if he should tell him that wine is pernicious and he never ought to drink any, he will think it ridiculous and will continue taking it. So he tells him `not yet'. And if he can keep his patient from it there is not much danger of its aggravating his complaint, he thinks he has done well; and then allows him to take a little once or twice a day in moderation; and the patient says the doctor has ordered it, and thinks it must be an excellent thing. But the occasions when wine or ale is required as a medicine are very few. When the strength is reduced to a very low ebb through disease, loss of blood, exposure to cold, or any other cause, it is universally allowed that to administer these stimulants is the very worst practice. It is like blowing strongly upon the very last spark of an expiring flame; there is the greatest risk that it will extinguish the little life that is left. Then since the unassisted powers of nature inherent in the body can raise it from such a degree of exhaustion as not to be able to bear stimulants stronger then cold water, do you not think that these powers, without the assistance of simple nourishment, can raise it from all lesser degrees of exhaustion? The brandy treatment has been extensively tried in cholera, but it is now abandoned in all parts of the world. If the debility is not so great that life is not destroyed by it (brandy), still it hurries on and makes more violent that reaction, that secondary fever which is most to be dreaded, and increases the tendency which there is to inflammation in the head and elsewhere. The common practice of applying to these drinks when chilled with cold, is equally injurious. It generally makes worse if it does not altogether bring on all the ill effects usually attributed to the cold.

In some case of spasmodic pain - of colic for instance - these liquors do give relief; but medical men produce the same relief by other medicines that are preferable. And in the hands of the multitude these fluids are highly dangerous; for if given when there is inflammation they increase it. It is therefore better in such cases to seek relief by ginger, pepper, or other aromatics which are equally efficacious.

So we find that the cases in which intoxicating drinks are required as medicines are very rare indeed, if any. And if they were useful as medicines, would that be a reason why they might be taken with impunity on every occasion? Would it not rather be a proof that they were injurious? When you hear of a person who is constantly taking medicine, whether it be from necessity or choice, you never expect him to be a long liver. Medicines are indeed a great blessing, but at the same time, their use is generally the substitution of a lesser evil for a greater.

Another great cause of the consumption of fermented liquors is a notion that a person requires them when he works hard. We hear them tell us 'Such as you that lead an easy life may do without, but a man that has to work as I have, wants a gill of ale now and then to help him get through it'. Now the proof that it contains little or no nutrition, ought to be sufficient to upset that fallacy; and there are plenty of well attested cases of men who, without one drop of these liquors, were as strong or stronger, and more able to endure fatigue than those who took them. And now that attention is called to the subject, these proofs are becoming daily more numerous. If as much industrious research had been employed about these matters, as in making discoveries about the moon and planets, and amongst the minute wonders of the insect kingdom, they would not now be subjects of dispute. With all our progress in natural history and the physical sciences, we are far behind some of the civilized nations of antiquity in knowledge of the things most nearly connected with our health and well-being. And while a British labourer has more comforts and luxuries within his reach than the Roman Emperors could boast, while he has ships on every sea conveying clothing and food and intelligence for him from every clime, and machinery performing for him the most delicate workmanship, he is ignorant of the means of applying these things to his advantage, and they often become his greatest curses.

The sole thing which makes these people strong (in addition to food) is exercise - exercise taken in a good state of health. And that diet is most conducive to strength which keeps the body in the most healthy and natural state, that food and drink which affords the necessary quantity of nutrition, and is at the same time least heating and stimulating. The circulation does require to be accelerated and the blood warmed sometimes, but it ought to be with bodily exercise, which adds fresh substance to the muscles, and increases the stock of vital energy, whilst all other stimulants diminish it.

A working man may drink a little ale, especially if it be along with his food, with more impunity than one who does not work, but still it does injury. Perhaps he does not see the difference between those who take it and those who do not, but until very lately there have been scarcely any who did not take it, except those who could not obtain it; and these are generally persons who are debarred from, or insufficiently supplied with, some things that are really necessary to health.

But they tell me, too, that they feel a direct advantage from a little ale. They say they can work better after it. They are inclined to believe their own feelings, but their feelings are fallacious. There is and must be a subsequent depression. If it was the effect of real nutrition, how could it be felt immediately? Before the advantage of nutrition can be realised, it must go through many processes, and even get into the blood, which could scarcely be on the same day.

Nurses, and people who go about the sick, make it an excuse for taking these liquors that they keep away infection; but that is so far from being the case, that the use of them not only makes people more liable to fevers, and, indeed, most complaints, but leaves them much less chance of recovery. It is also said that ale is necessary for mothers while giving suck, but that is a disastrous error; and I would wish to speak emphatically to mothers when I say, as you love your infants, as you value their ease, their health, and their future welfare, let not that stream which is their first nourishment, be polluted by flowers of the soporific hop-plant, and the irritating and inflaming alcohol contained in beer; but let it be pure and healthful, formed of simple food, whilst living according to the dictates of nature.

Another cause of entertaining these evil spirits and the drinks which contain them, is the prejudice which there is against cold water. Folks must have something else. I can drink it in moderation when I am thirsty, and I never tire of it. You have all heard of the dreadful disease produced by the bite of a mad dog. It is called hydrophobia, from two Greek words signifying a dread of water, which is one of the symptoms of the disorder. But awful as this disease is, there is another hydrophobia, which is ten thousand times more fatal. The first hydrophobia happily occurs but at long intervals, and at place distant from each other. Many medical men have an extensive practice, and die without seeing it. But the dread of water which makes people seek to quench their thirst with anything rather than the limpid element, is the cause of daily and innumerable deaths, and of the greater part of the misery, poverty, and strife, that we see around us. One cause of this antipathy to water is the severe disorders, and sometimes even sudden deaths that are now and then occasioned by a quantity of very cold water, when heated by exercise; but these mischiefs are produced simply by the coldness of it. As much cold ale would do as much harm.

Another cause of this antipathy is the fact that some tedious and even dangerous complaints are occasioned by the water that people habitually use. But it is the impurities which it contains that are to blame; and you do not escape from the danger by flying to fermented liquors, for you still get water and more of it, too. The way to get water pure is to distil it. Those huge stills in different parts of the country that pour forth evils amongst mankind in greater proportion than the fabled Pandora's box, may, by distilling water instead of spirit, be made to be the fountains of health; and wherever there is a steam engine, a very trifling expense in a few additional pipes would condense the steam that now flies away into the air, or is otherwise wasted, and supply plenty of the purest water to the whole neighbourhood. But you in Netherdale, have no occasion to be afraid of the water which comes gurgling from the hills in unrivalled softness and purity. I believe that the noted healthfulness of this district, in spite of the lead mines and mills, and the good stature and fresh looks of the inhabitants, is as much to be attributed to the purity of the water they drink as to the air they breathe.

We have thus enumerated some of the causes of what is called the temperate use of these pernicious things, that the temperate use of them which is the chief cause of intemperance. Yes, almost the sole cause. For nobody becomes a drunkard all at once; that is contrary to the nature of things. A taste for the drink is first acquired in the school of moderation. The society of drunkards is not alluring. No young man would go amongst them to begin with. And no one would fly to drink as a refuge from grief or disappointed ambition who was not previously well acquainted with its effects. And, moreover, it is the moderate use of them by respectable people that gives these liquors all their plausibility. When they are used by sober tradespeople in transacting business, it would seem that there is something creditable in them. When they are given to visitors, do they not look like the very type of hospitality? And when ladies drink wine to each other at a ball, must it not be the very essence of politeness and refinement? When used at a wedding, is it not the promoter of harmless mirth? And at a funeral it is associated with our most grave and solemn contemplations. On the other hand, if none but drunkards used these fluids, the very business of a brewer or distiller or vendor of them would be infamous. Let me beg you to pause before you determine whether your conduct and influence shall assist in upholding all the legion of woes, ignorance, and depravity, which keep the world enthralled; or, whether you will assist in the great moral reformation which is already taking place, and towards which every individual has it in his power to contribute his share.

My friends, this is a subject which will bear viewing in an endless variety of directions. One might deliver a thousand lectures on it without any repetitions. Temperance societies afford an excellent opportunity for medical men to enlighten the public on very many points connected with their health, a great deal of useful information might be given on many subjects connected with our profession, without touching on anything above the meanest capacity; and it would cause medical men to get on much more smoothly, and enable them to do a great deal more good.

In concluding, let me beg of you to examine this subject attentively and on all sides, and to keep your eyes open to the effects that will be produced amongst members of our society. If fairy tales were sometimes true, and if some kind guardian sylph were to tell me to wish a good wish to the folks of Netherdale before I left them, and if it should be fulfilled, I would wish, as one of the greatest blessings that could be conferred upon them, that they might be enabled to see intoxicating liquors and the effects of them in their true light. But give the subject your serious consideration, and I have too good an opinion of the cause and of your judgement to fear the result.

Source: Snow,Thomas (edited). Doctor's teetotal address delivered in 1836. The British Temperance Advocate, 1888 in Galbraith, S. Dr. John Snow (1813-1858) -- His Early Years, 2002.

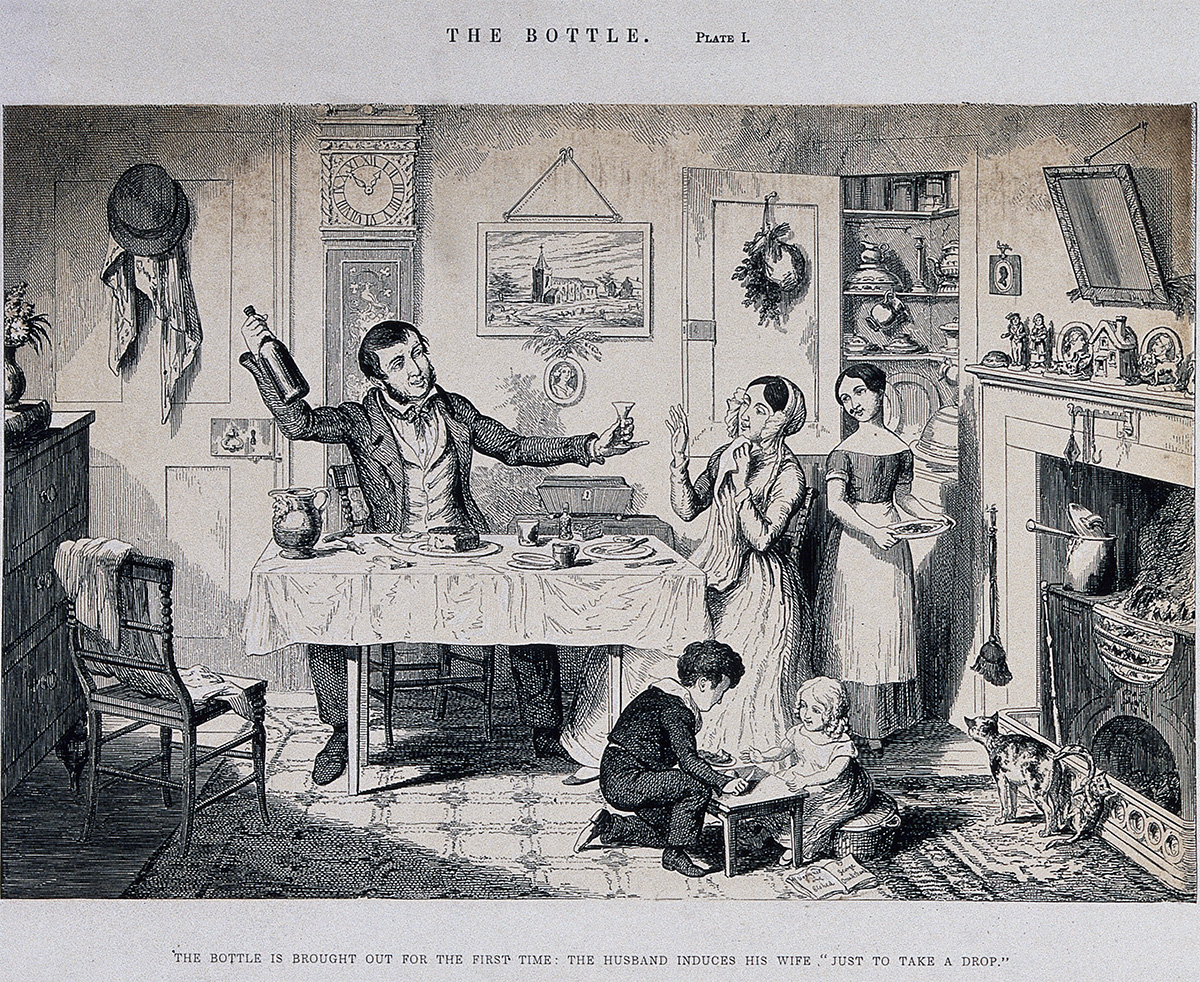

Cruickshank, "The Bottle", Etched Plates 1-8

When 17-year-old John Snow in 1830 first became enamored with the Temperance Movement during his apprentice years in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, he was not alone. Temperance societies promoting abstinence from alcohol had sprung up through out England, and became quite popular in the early to mid-1800s. In addition, Snow during his Newcastle-upon-Tyne and Pateley Bridge years adopted a vegetarian lifestyle, restricting meat from his diet, adding to an image as somewhat of a social maverick.

In some respects, this maverick tendency helped him in later years when following his epidemiological pursuits. Snow argued against the prevailing notion that cholera was caused by bad smells or bad air arising from decomposed organic matter (i.e., the miasma theory that was later debunked). Instead he posited that cholera arose from very small organisms circulating in water (the actual cause, discovered long after his death, was by a toxin of a subset of the bacteria Vibrio cholerae.)

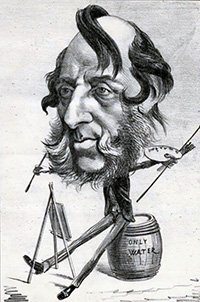

The famous British cartoonist and illustrator George Cruikshank (1792-1878) was part of this temperance movement as well, also being a social maverick, although not as early in his temperance advocation as John Snow. Cruikshank in 1847 produced a series of eight etchings that illustrated "The Bottle." Earlier, he had revealed that his father had been an alcoholic. He then shared that his troubled father, following a drinking contest, had died of alcohol poisoning. Cruickshank further revealed that he himself had been a drinker until he stopped, following an abstinence pledge in 1847 when the series "The Bottle" was published.

Dr. John Snow, then aged 34 when the series came out, likely shared the eight prints with others when he talked in support of the temperance movement.

The Bottle Plate I

The Bottle is brought out for the first time. The husband induces his wife "just take a drop."

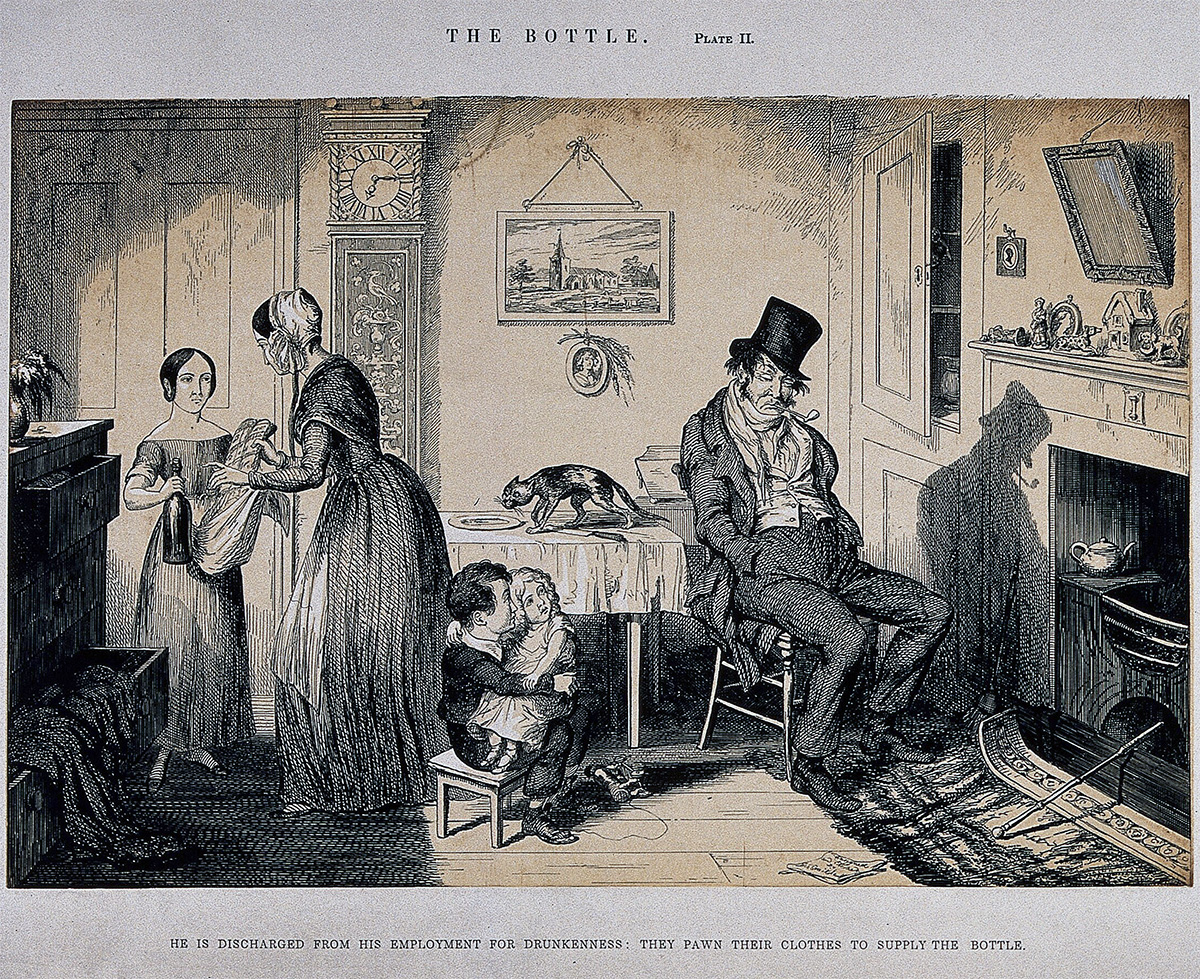

The Bottle Plate II

He is discharged from his employment for drunkenness: they pawn their clothes to supply The Bottle.

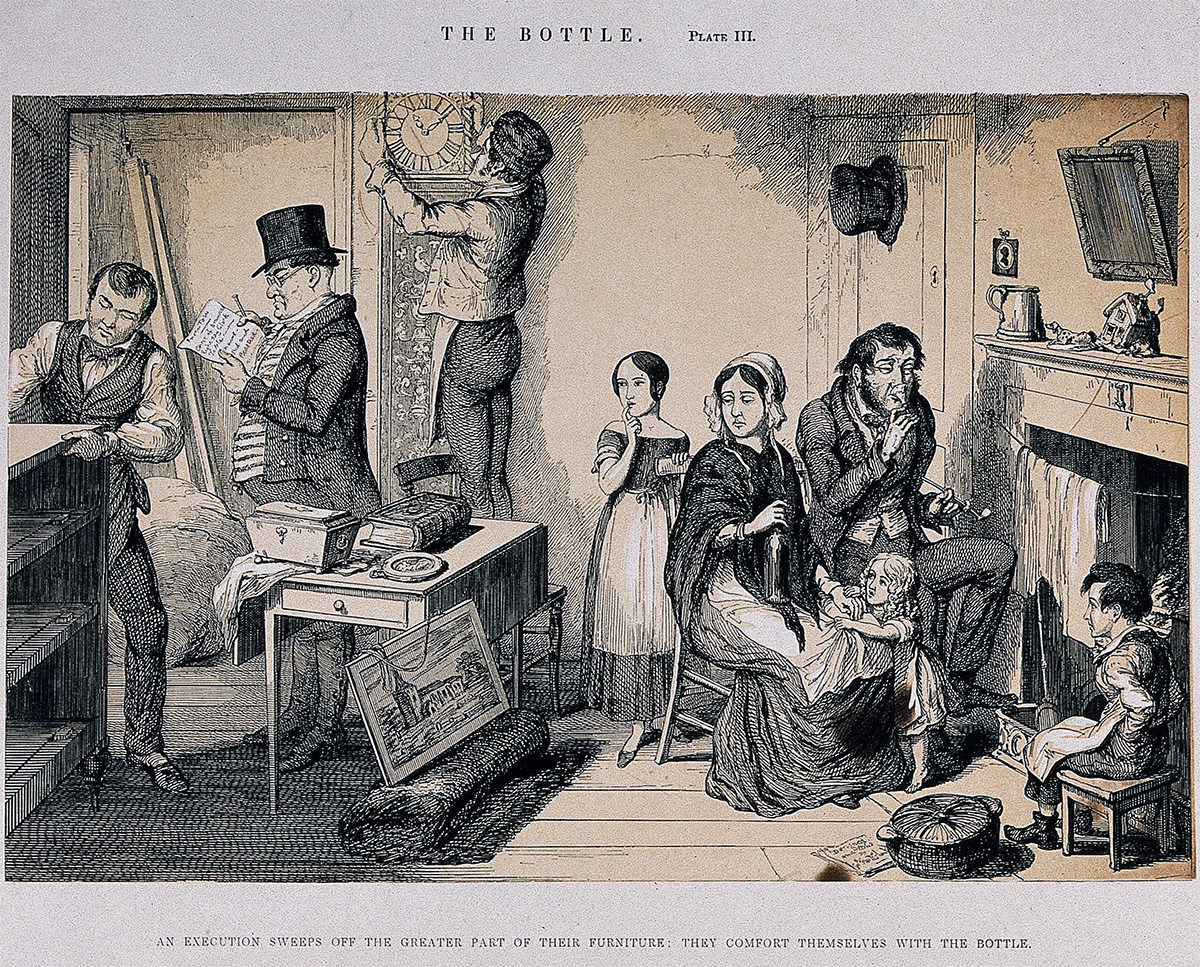

The Bottle Plate III

An execution sweeps off the greater part of their furniture: they comfort themselves with The Bottle.

The Bottle Plate IV

Unable to obtain employment, they are driven by poverty into the street to beg, and by this means they still supply The Bottle.

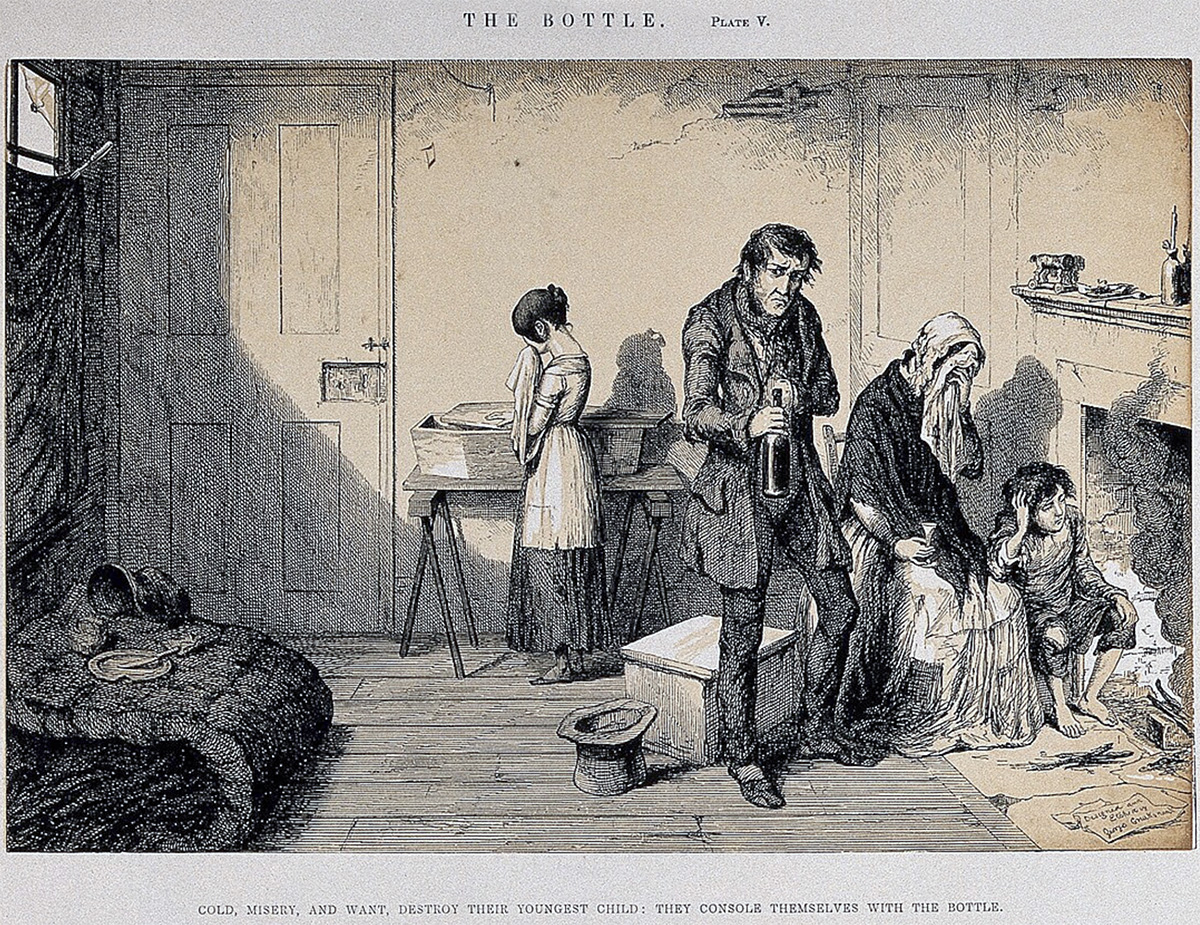

The Bottle Plate V

Cold, misery, and want, destroy their youngest child: they consule themselves with The Bottle.

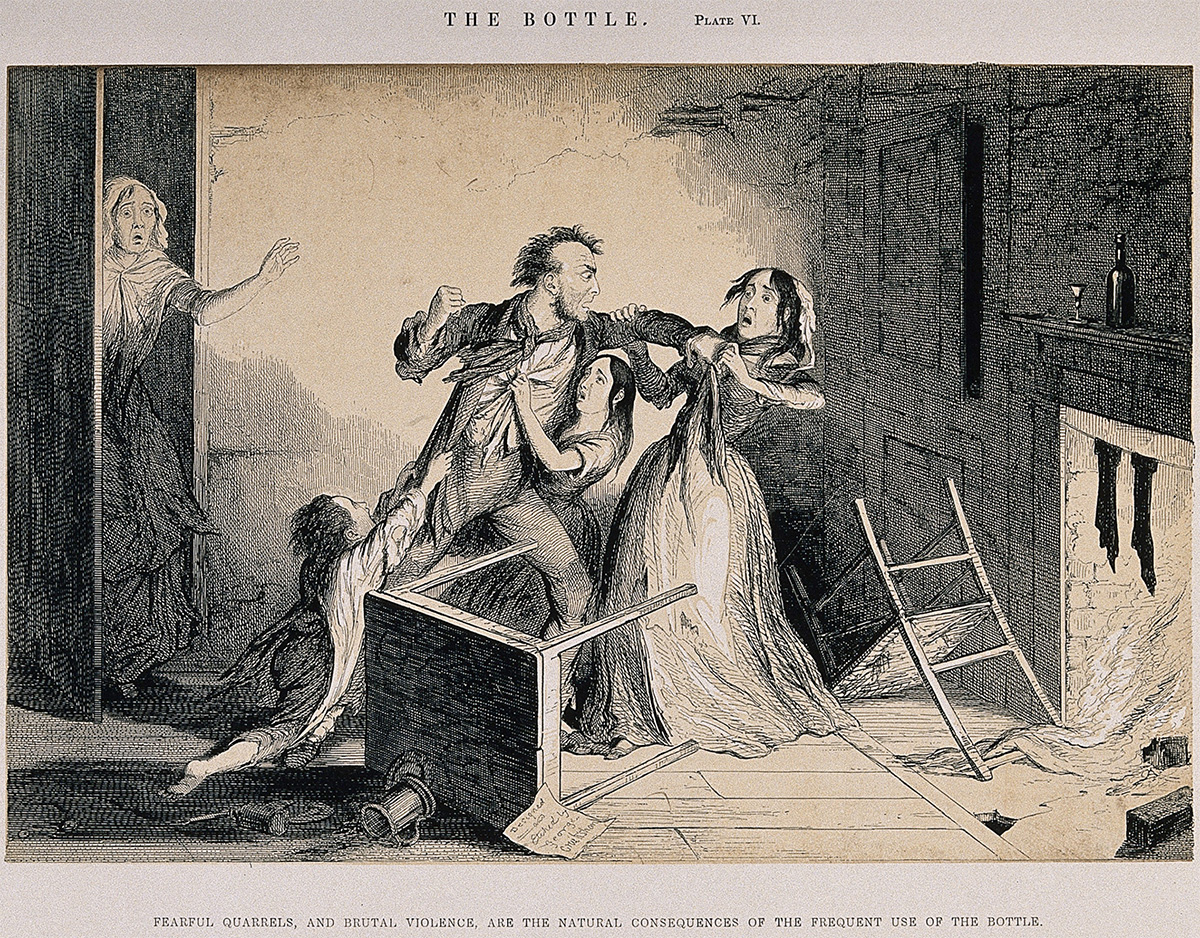

The Bottle Plate VI

Fearful quarrels, and brutal violence are the natural consequences of the frequent use of The Bottle.

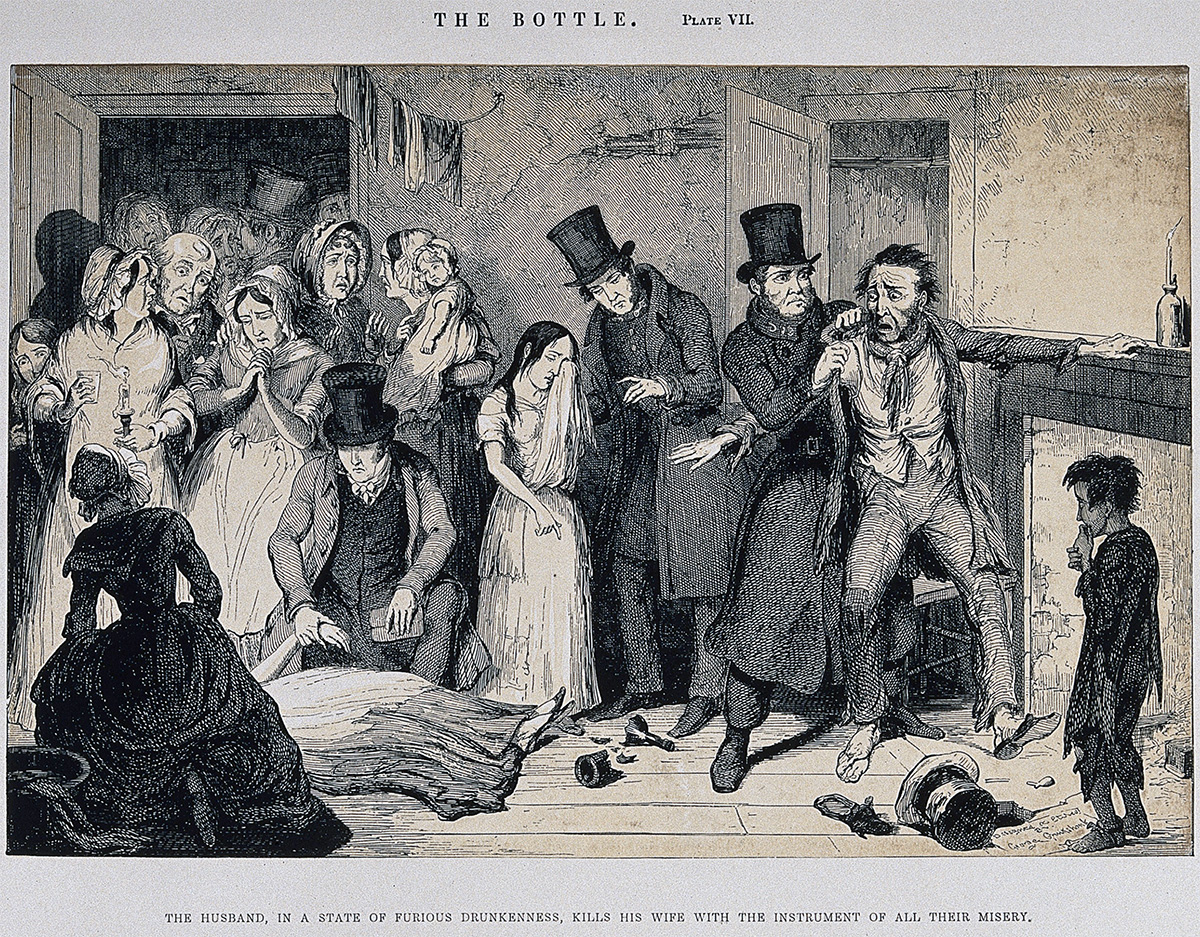

The Bottle Plate VII

The husband, in a state of furious drunkenness, kills his wife with the instrument of all their misery.

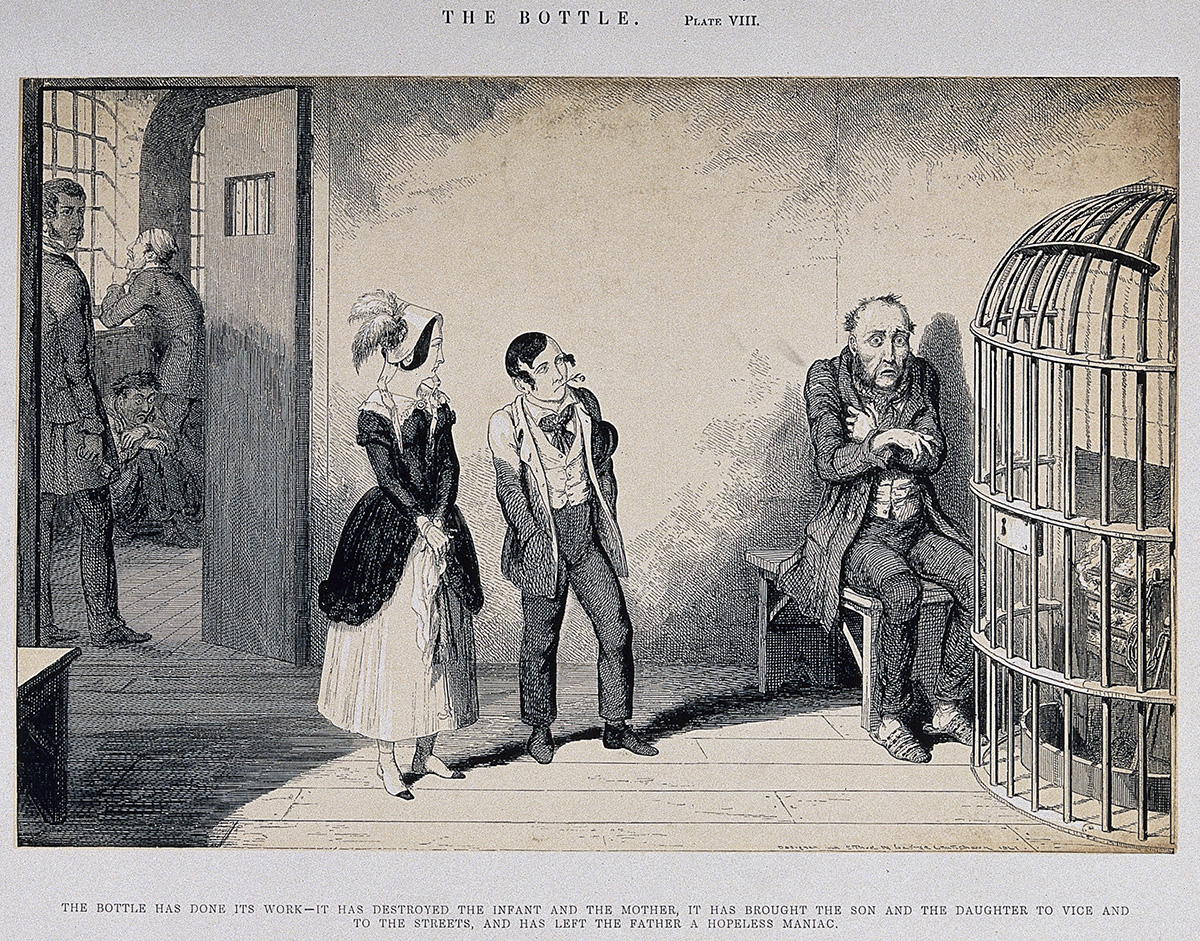

The Bottle Plate VIII

The Bottle has done its work - it has destroyed the infant and the mother, it has brought the son and the daughter to vice and to the streets, and has left the father a hopeless maniac.

End of Aside - The Temperance Movement in England during the 1830s

End of Aside - The Temperance Movement in England during the 1830s

THE MYSTERIOUS UNCLE IN YORK

Questions

John Snow grew up in a poor household in York, England. When he decided on a medical career, likely his family was delighted but also concerned with the potential cost. In 1827 while still a young boy of 14, John Snow traveled far from home to Newcastle- upon-Tyne to apprentice with William Hardcastle, followed by a second and third apprenticeship with John Watson and Joseph Warburton. Typically the cost would have been 100 pounds. Then later in 1836 when he went to the Hunterian Medical School in London, he paid a fee of 34 pounds. Who helped and encouraged John Snow in these early years? Who assisted Snow's family in paying for the apprenticeship and education? Perhaps the answers to these questions lie with his favorite uncle, Charles Empson (1794-1861).

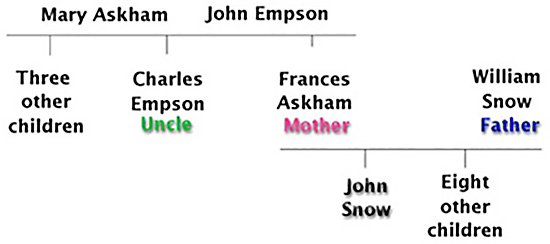

ORIGIN

In 1794, Charles was the third child of Mary Askham and John Empson, a weaver in York. Charles was the younger brother of Frances Askham, who was born in 1789 before Mary Askham and John Empson were formally married in 1792. Thus Frances assumed the last name of her mother, different from that of her brother Charles. Later Frances married William Snow and they gave birth to John Snow, perhaps named after his maternal grandfather John Empson.

Not much is known of Charles Empson's early years except that he yearned to travel. His family was not wealthy, with the father having been a weaver. When Charles was 29, he left England in June 1824 for South America, and spent time in the northern section of the continent in what is now Colombia.

He traveled with his good friend, Robert Stephenson (1803-1859), whose father George was a famous railway engineer in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Robert spent his first twelve years in Killingworth, a small town to the north of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, where his father was employed as an engineer at the local colliery. Robert did his early schooling in Long Benton, a suburb of Newcastle-upon-Tyne to the south of Killingworth.

In 1827 when John Snow was 14 and considering a medical apprenticeship away from home, Uncle Charles Empson and his friend Robert were finishing their three-year South American journey and continuing to New York.

Snow, being an impressional young man of 11-14 years, thought highly of his adventuresome uncle, appreciating his artistic eye and his friendly temperament, filled with a traveling spirit and a sense of independence. These traits likely appealed to young John Snow who would keep Charles Empson close to his heart.

Empson's art creations from that period were widely viewed in the years that followed. His vivid watercolors arising from the Colombian trip are still favored in current art markets, including "Scarlet Star" to the left and "Grape Fruit" to the right.

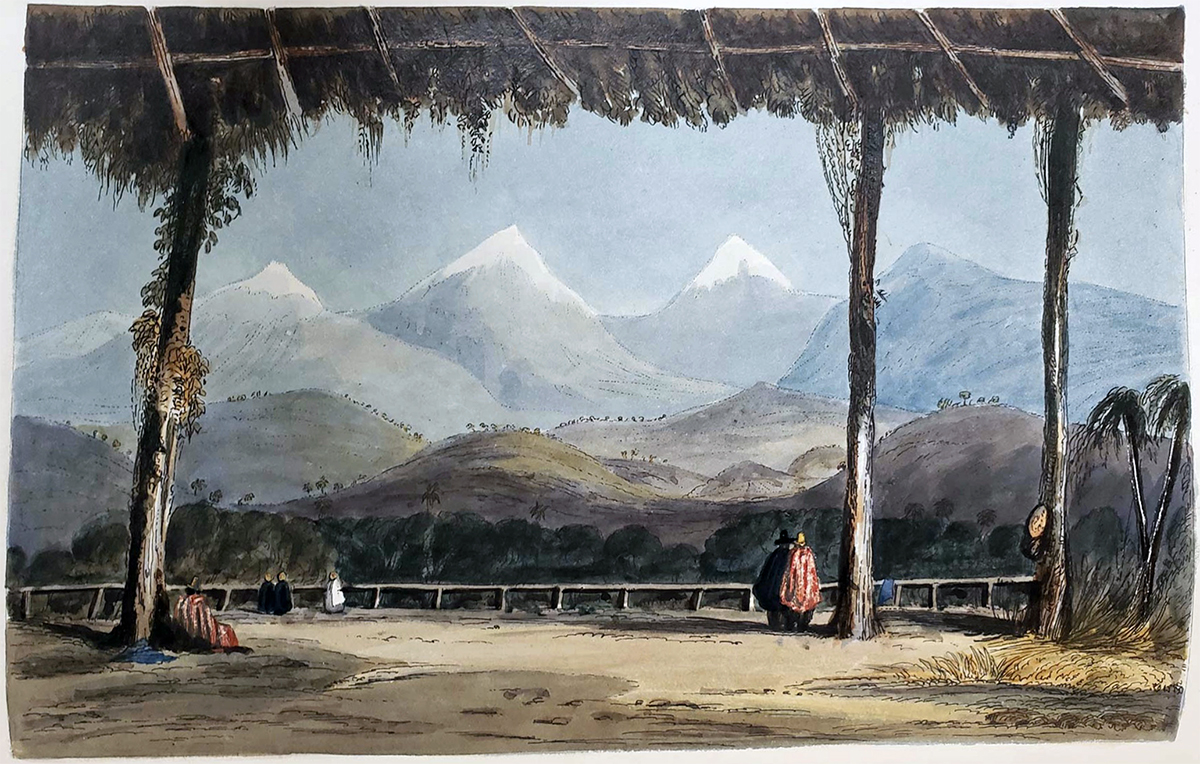

High among Empson's most famous paintings is "The Rustic Corridor" (in present-day Colombia). It reflects "on humanity's place in nature, depicting the vastness of the Andes as observed by solitary figures through a "rustic window."

Source: Empson, Charles. "The Rustic Corridor," (1836), Universidad de Los Andes, Colombia, 2025.

Robert Stephenson's family doctor was William Hardcastle, who had a practice on Westgate Street in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Hardcastle was also a close friend of Charles Empson. Knowing of his nephew's interests in medicine, Charles likely encouraged Robert to write Hardcastle to arrange for the apprenticeship of John Snow.

The two friends left the Colombia region at the end of July 1827, one month after John Snow started his apprenticeship with William Hardcastle. They brought with them precious objects of pre-Colombian art, including some gold artifacts which Charles Empson later exhibited in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Unfortunately, some of their possessions were lost in a shipwreck at the entrance to New York harbor.

After spending time in New York city, Charles and Robert went on a walking tour of New York State and Canada, traveling as far as Montreal. They arrived in Liverpool, England in November 1827.

CAREER

After his three-year journey, Charles Empson settled in Newcastle-upon-Tyne and where he started a business as a fine art bookseller. The business flourished until 1834, when he relocated to Bath, a small town of 57,000, known for its religious Bath Abbey, hot springs, eloquent homes, and appreciation of art and literature (see map at right, and 1856 map below with red dots at Bath and London).

A year earlier John Snow had also left Newcastle-upon-Tyne, but for Burnopfield to attend the second of three medical apprenticeships.

In Bath, Charles Empson was described as a museum keeper or perhaps more accurately, as an art dealer. He became increasingly prominent in local society. One of his acquaintances was Charles Louis Napoleon (1808-1873) who was living in Bath and later proclaimed himself to be Emperor Napoleon III of France (see at left).

Decades later, John Snow and uncle Charles Empson traveled to Paris to meet with the Emperor. The visit also gave Snow an opportunity to present his work on cholera to the Institut de France.

In the late summer of 1836, John Snow again visited Uncle Charles Empson, but this time in Bath. He was in the midst of a long walk from York to Bath, and then on to London to begin his formal medical education.

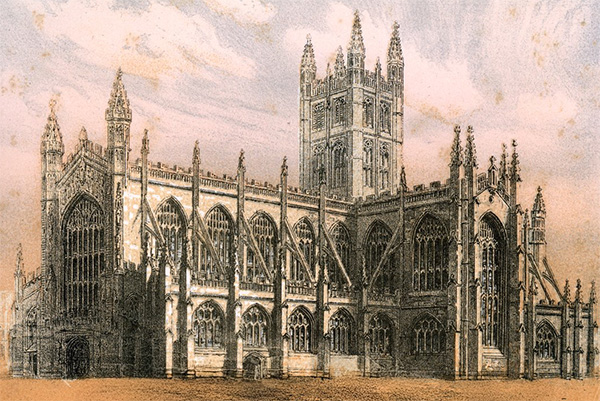

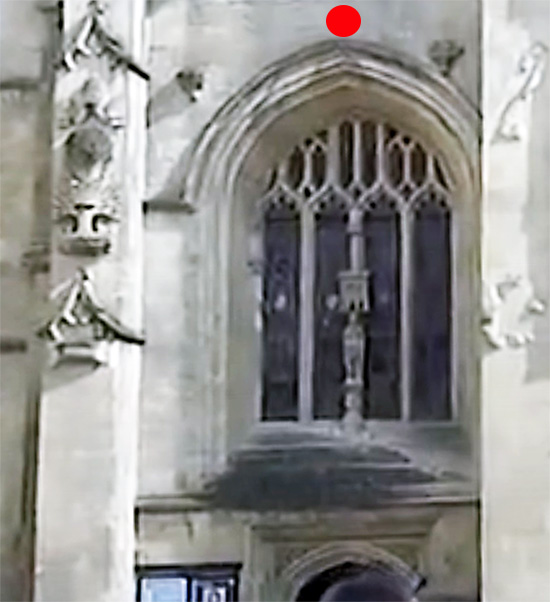

The Bath Abbey is a parish church of the Church of England. Its formal name, when not using the shortened "Bath Abbey", is The Abbey Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul. Here is what the church looked like during Empson's time in Bath. The style is Gothic, with fan vaulting, large windows, and flying buttresses added for support in the 1830s.

Empson lived in two homes while in Bath, first from 1836 to 1843, home was at 9 Cleveland Place in the northern section of town, next to the Cleveland Bridge over the River Avon (upper red dot in Moule's 1836 map at right). In the same building he had a museum which showed both paintings and historical works.

He then moved closer to the Bath Abbey (green dot) at 7 Terrace Walk (lower red dot). Again his building was listed as a museum, but was more an art gallery since it also featured the work of local artists.

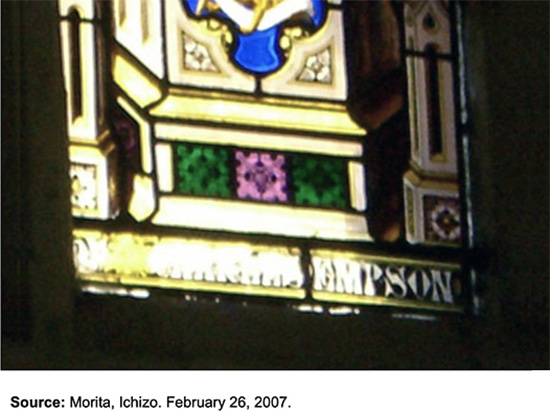

To more clearly view his second home at 7 Terrace Walk, see the red dot at Terrance Walk in the map at right. Also shown in the small map is a second red dot in the Bath Abbey. It focuses on the location of a four-panel stained-glass window in the Abbey's northwest corner. Following his death in 1861, friends of Charles Empson made a sizeable donation to the Bath Abbey in his memory, paying for the creation of the four-panel window.

At left is the northwest entrance to the Bath Abbey showing the outside view of the four-panel stained glass window (red dot at left and in closeup at right) where Charles Empson is remembered inside the Abbey.

The four panel stained glass window is named, The Evangelists, St. Matthew, St. Mark, St. Luke, and St. John.

In the inner Abbey, the four panel window appearing below the red dot radiates spiritual forms and colors, as might be expected in a beautiful cathedral, but offers an addition surprise - a memorial for Charles Empson

At the bottom the four Evangelists is the word, "EMPSON," referring to Charles Empson. An inscription at the base of the four panels of the Evangelists reads: ""In affectionate remembrance of Charles Empson of this City - born 1795 [mistake, actual birthdate 1794], Died 1861".

It goes on to state: "Erected by public subscription, that the memory of a good and estimable citizen is perpetuated."

He was 67 years old at the time of death, and passed three years after Dr. John Snow, his famous nephew.

TWO PORTRAITS

A painting of Charles Empson is now owned by the descendants of John Snow's brother Thomas (1821-1893).The undated portrait is believed to be painted by Willis [or Willes] Maddox (1813-1853), a Bath artist who later moved to London.

There is a photo of Charles Epsom taken in his later years, but with an anonymous photographer and with no date.

DEATH

John Snow died in London in June 1858. Three years later, in June 1861, Charles Empson was sick for three days with what probably was pneumonia and subsequently died on June 25, 1861. He was 67 years old.

At the time of his death, Empson's estate was valued at 8,000 pounds. He left some of his estate to various charities in Bath, but most of his assets were left to his family members, including his sister Frances (i.e., John Snow's mother) who outlived both her brother and son John. Similar to nephew John Snow, Charles Empson never married and left no sons or daughters to inherit his wealth.

Empson was buried in Brompton Cemetery in London, in a grave marked by a low tombstone next to that of John Snow. He probably reserved the plot when John Snow died.