Stream 5 - Additional Items

k: Renaud Piarroux - "The Modern John Snow"

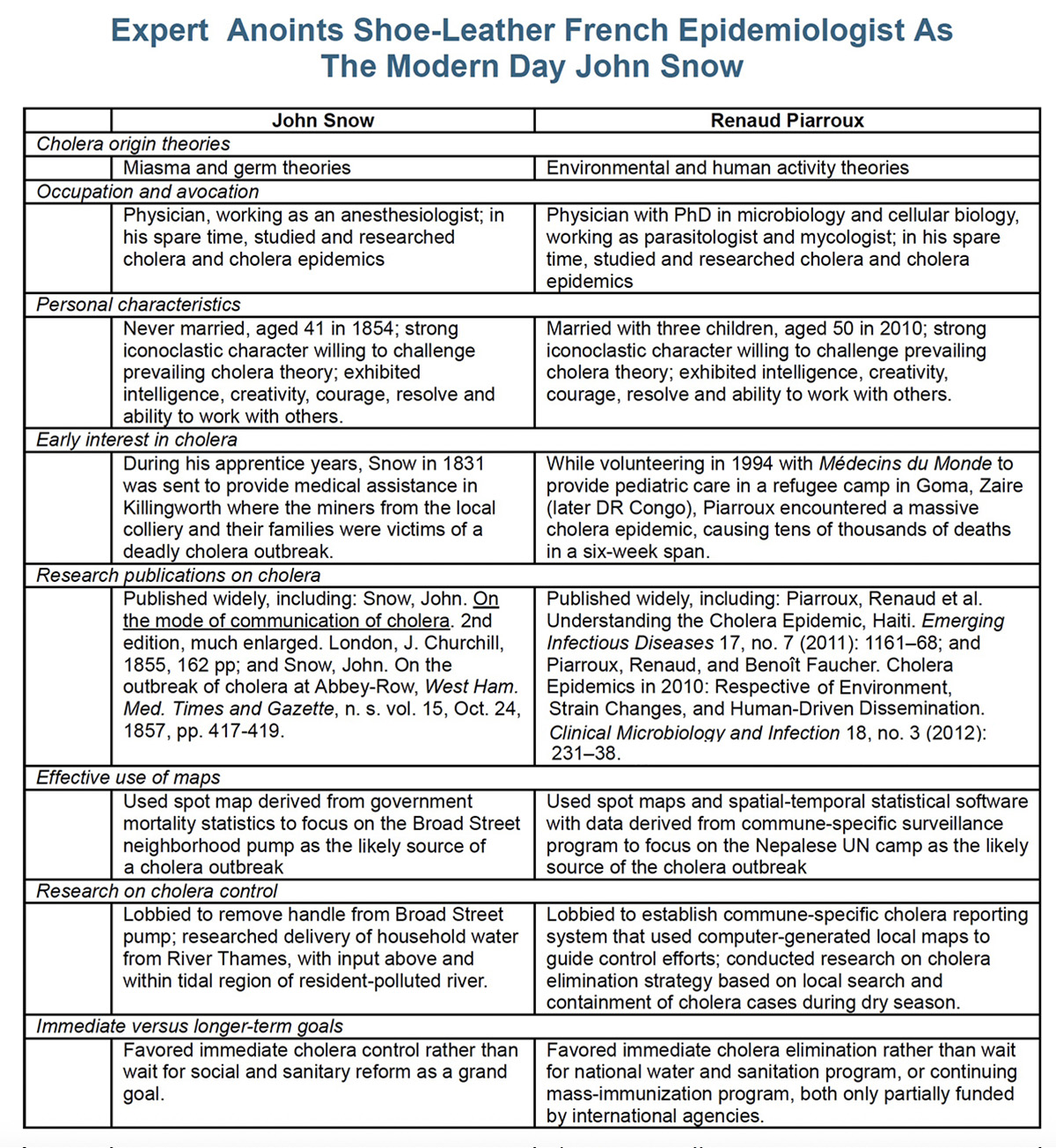

While there can be only one John Snow, another epidemiologist has appeared on the scene who shares many characteristics of John Snow - French epidemiologist Renaud Piarroux, M.D., Ph.D. The true story of his investigation of cholera in Haiti was told in Deadly River - Cholera and Cover-up in Post-Earthquake Haiti, 2016, authored by Ralph R. Frerichs.

On June 3, 2017 Renaud Piarroux was officially inducted as chevalier or knight in the French la Legion d honneur or Legion of Honor. Given the choice of location, Piarroux requested the ceremony be held in Saint-Etienne-d Albagnan, a picturesque village in southern France, the site of his marriage years earlier. Presiding over the ceremony was Bernard Meunier, President of the French Academy of Sciences (at left). Also participating were Ralph R. Frerichs, author of Deadly River (at center-right) and Philip G. Alston, the United Nations Special Rapporteur for Extreme Poverty and Human Rights (at right).

Introduction to Renaud Piarroux and Cholera in Haiti

The following article by Tim McGirk is a book review, but also serves as a fine introduction to Renaud Piarroux, M.D., Ph.D., offering a sense of why he should be considered the "modern John Snow." Rather than a dual between two historical theories of cholera that beset John Snow (i.e., germ theory versus miasma theory), Renaud Piaroux in Haiti confronted two theories of cholera origin (i.e., environmental versus human activity) that beset him as well. The environmental theory was backed by many scientists and international specialists, while the human activity theory had a smaller following. One theory featured innocence with no humans to blame, while the other focused on human neglect, needing to be held accountable.

Powerful national and international agencies also became involved, wanting people to believe that cholera which had come to Haiti in 2010 and caused one million or more cases and about 10,000 deaths, was due to genomic recombination of naturally occuring Vibrio cholerae in brackish coastal waters (i.e., human innocence) rather than brought from Nepal by infected United Nations Peacekeepers, who's sewage was dumped late one afternoon into the main river that flows east to west through the country, setting off in coming days a major epidemic.

John Snow had many doubters in the early months of his investigations. The same occurred with Renaud Piarroux, although the truth was easier to come by as more scientists considered the evidence, shared widely over the internet. Now with both Snow over many years and Piarroux over a shorter time-frame, the tide has turned, and doubters are fewer in number. Some, however, still face the "inconvenient truth," worrying about potential impact on the reputation of national and international organizations that were less forthcoming.

Tim McGirk, Investigative Reporting Program

Tim McGirk, was familer with Haiti, having been the Time Magazine bureau chief for Latin America, and at the time of his book review, was a lecturer at the Graduate School of Journalism at the University of California, Berkeley. He and his UC Berkeley graduate students in the Investigative Reporting Program became interested in the unique nature of the 2010 Haiti cholera drama.

When Dr. Renaud Piarroux presented at UCLA in August 2013 (three years after the epidemic had started), McGirk and an assistant traveled from UC Berkeley to UCLA to conducted a lengthy interview with him. Thereafter, members of the Investigative Reporting Program went to the place in Haiti where cholera was proven to have started, then interviewed persons in a local village in Creole using a Haitian journalist as translater. They learned that "many" newly arrived Nepalese peacekeeping soldiers had been vomiting and were sick in the United Nations camp where the cholera epidemic dramatically sparked in late 2010.

This final nail in the evidentiary coffin amidst the prior evidence of Piarroux and others confirmed that the nationwide cholera epidemic was inadvertedly initiated and then covered up by United Nations peacekeepers and others.

Some years later when the book Deadly River was published, McGirk submitted a book review, shown below, with an eye-catching title.

DEADLY FILTH, CARTOGRAPHIC DECEPTION, TRAIL OF VICTIMS, MICROSCOPIC GODZILLAS

Source: McGirk, T. American Journal of Public Health Vol 107, No 12, pp 1851-52, 2017.

Ralph Frerichs, professor emeritus of epidemiology at UCLA, has a penchant for detective stories. In Deadly River, Frerichs has written a masterful epidemiological whodunit set in Haiti, where the killer

was swiftly identified as cholera.

But other culprits emerged, as Frerichs describes in scientific yet lively prose: international health agencies and the United Nations (UN) tried to hide the role of UN soldiers in accidentally

bringing the disease to Haiti.

In January 2010, a 7.0-magnitude earthquake slammed Haiti. Its epicenter was near Port-au-Prince, and the aftermath was infernal. More than 8,000 people died. Hundreds of thousands were left injured and homeless. Hospitals and government buildings crumbled. As international aid agencies scram-bled to help, experts warned that the filth and the lack of clean water and sanitation facilities could cause deadly outbreaks.

Unsurprisingly, it happened. Not immediately, but nine months later in October 2010, cholera struck. But it did not break out in the shanty-towns or refugee camps of Port-au-Prince, as health experts had anticipated. The first cases surfaced along the Artibonite River, an area unscathed by the earth-quake. Even more perplexing: Haiti may have been cursed with hurricanes, quakes, and military coups, but historically it had been spared cholera. The disease scythed across the island at murderous speed, claiming hundreds, then thousands of lives in the first weeks.

Enter Renaud Piarroux, the epidemiologist dispatched by the French government to Haiti. He arrived two weeks after the disease had been identified as vibrio cholerae, which can be passed on by contaminated water or food or by one person infecting another. Experts agree that the first order of business in containing an epidemic is to identify its point of origin. That would be Piarroux’s focus when he arrived in Haiti. It would not be so easy.

Even before leaving the Universite d’Aix-Marseille, where he teaches parasitology and mycology, Piarroux began scouring the Web sites run by international health organizations to track the speed and direction of the Haitian epidemic. He found several puzzling anomalies: the earliest disease map - published by Haitian health authorities and the Pan American Health Organization, a regional office of the World Health Organization (WHO) - showed the first cases near Mirebalais, a farming town along the Artibonite, Haiti’s largest river. Yet subsequent maps issued by the UN’s Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs claimed the first outbreaks happened further downriver, dozens of miles away from Mirebalais.

Most curious of all, a press communique was put out several days later by MINUSTAH, the UN agency in charge of its peacekeeping force in Haiti, which had nothing to do with medical aspects of the epidemic. Nonetheless, this agency claimed that the first case of cholera occurred on September 24, 2010 in the Lower Artibonite region, “a populated place where people live in precarious conditions without drinking water or latrines.” This press release shifted the date of the outbreak earlier by nearly three weeks, and the location from the hills of Mirebalais down to the Caribbean coast, a distance of 54 miles. This discrepancy bothered Piarroux before he even set off for Haiti. It was only later that the French scientist began to wonder if he was witnessing “epidemiological falsehood” and “cartographic deception.”

It soon became clear to Piarroux that it was deception, on an epic scale. Piarroux is the kind of gumshoe investigator who prefers getting out in the field to sitting at a desk. On arrival, he insisted on being taken to Mirebalais. By then, press reports had pointed to a UN peacekeeping camp of Nepali soldiers as being a possible source of the cholera, and several reporters who visited the camp, but were not allowed inside, noticed pipes leaking from the latrines into nearby fields and streams. A quick Google search revealed that a cholera outbreak had swept Kathmandu and its environs shortly before the Nepali troops left for Haiti. Frerichs makes a compelling case that not only were the UN agencies aware of this early on, but so too were the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the WHO. Hunting for the origins of the disease, they all insisted, would be a distraction from coping with the epidemic.

Haiti was only weeks away from a politically charged election, and there was a genuine fear that if word got out that MINUSTAH was to blame for inadvertently bringing in cholera, it could lead to riots aimed at the UN and the international aid agencies. MINUSTAH, in particular, was seen as an occupying military force and much loathed. It was reported that the beleaguered Haitian president, Rene Preval, had little choice but to go along with the UN cover-up. Frerichs, however, thinks Preval discreetly tried to reveal the truth.

As Piarroux was about to leave Haiti, a stranger handed him an envelope. Inside was a report from Haitian health workers who had rushed to Mirebalais on October 18, after the first cases of a violent and lethal watery diarrhea. The trail of victims led the health investigators straight to the gates of the UN camp of Nepali peacekeepers. But they were refused entry. The stool samples taken from victims were later analyzed in a Port-au-Prince government lab, run under the CDC’s auspices, and shown to be cholera. Frerichs insists that the CDC would have been privy to these early reports. He speculates that even though these reports were suppressed, the Haitian president may have defied the UN and made sure that Piarroux was slipped a copy.

The UN tried to give cover to its peacekeepers. It insisted that tests on the Nepali soldiers and the base itself came back negative for cholera. Critics, Piarroux among them, argued that these samples were taken weeks after the disease was gone. Household bleach would have killed any trace of the cholera organism from the sanitation facilities from which the environmental samples were drawn. The UN’s insistence on its own innocence was given another knock by analyses of the vibrio cholerae showing that the organisms found in Haiti were similar to South Asian strains. Later genome studies showed the two strains were virtually identical.

As pressure mounted on the UN agencies and more health experts were coming round to Piarroux’s conclusions, the UN set up an independent panel of experts to look into the matter. These scientists mostly favored an environmental hypothesis, which assumed that cholera had been lying dormant in the waters off Haiti but, like zillions of microscopic Godzillas, was roused into a pathogenic state by the earthquake and changes in temperature and water salinity. That theory troubled Piarroux: how could the organisms have swum up the river from the coast to Mirebalais, where the first deaths occurred? The panel ruled out the environmental hypothesis but stopped short of pointing a finger at the Nepali peacekeepers, concluding that the outbreak was caused by “a confluence of circumstances ... and was not the fault of, nor deliberate action of, a group or an individual.”

The UN has yet to accept full responsibility for the cholera outbreak in Haiti and probably never will. Other biological disasters inevitably will arise elsewhere. Hopefully, says Frerichs, the global health organizations and the UN will react to the next crisis with more transparency and honesty than they did in Haiti.

French Epidemiologist Anointed As “Modern Day John Snow”

Interview with Deadly River author

Source: Interview: 1) Officials accused of covering up the source of the outbreak, and 2) French epidemiologist anointed as "Modern Day John Snow." Epidemiology Monitor, May 2016.

Ralph Frerichs, well-known UCLA epidemiologist and creator of an extensive website on John Snow, has spent four years writing a book about the introduction

of cholera in Haiti and the medical detective work of French epidemiologist Renaud Piarroux. The Epidemiology Monitor first wrote about Frerichs and his

involvement with the cholera outbreak back in 2013.

Back then, Frerichs told the Monitor he got “terribly intrigued” by the failure of early investigators to pinpoint conclusively the source of the outbreak. He felt

that something was not quite right with the reports he was reading because “I could not believe they could not wrap it up. They were omitting all the basic

things and tip-toeing around the findings.”

In 2013, Frerichs was uncertain about whether or not Piarroux was truly a John Snow equivalent. He told us Piarroux was a worthy candidate but he wanted to

wait until after the book was finished to decide. His hesitation has now disappeared as he told the Monitor this month, “I am now calling Dr. Renaud Piarroux

the ‘modern John Snow’ for his excellent epidemiological manner and skills as described in the book." (See Frerichs' table below of Side by Side Comparison ).

When he faced the source of the initial outbreak and immediately recognized that the personnel were serving one of the most powerful organizations in the

world, he did not flinch. I was hesitant in case other candidates appeared, but alas, none did. Piarroux was the man, a worthy hero.”

We interviewed Frerichs to get his perspective now that the book has been published.

EM: Deciding to write a book is a big commitment or big decision. What tipped you to decide to write this book?

Frerichs: I first became aware of the Haiti cholera outbreak in October 2010 shortly after it began. At the time I was already retired for two years but still teaching a summer course on

epidemiology at UCLA and was looking for interesting outbreak examples to share with my students. I was initially surprised when epidemiologists and others

at CDC and PAHO commented that they were too busy to find the source of the outbreak, and that the origin of what would soon become the world’s largest cholera epidemic

might never be identified. Shortly thereafter, I decided to add a section to the John Snow website on the Haitian cholera outbreak, and included comments

here and there about news items and related articles. In early November 2010 French epidemiologist Renaud Piarroux arrived in Port-au-Prince, requested by

the Haitian government. In January 2011, I wrote Piarroux in Marseille, having read his consultant report. We immediately hit it off. He shared with me both

his findings and correspondences, deepening my interest. After his seminal article appeared in Emerging Infectious Diseases, we noticed that there was still

confusion about how cholera came to Haiti, so we addressed this in an article that summarized the etiological roll of Nepalese peacekeepers of the United

Nations. The story kept getting bigger, and eventually we decided to write a book that covered much more than was possible in a journal article. While we

both labored equally on the book, Piarroux was personally more comfortable having me be the story-teller and him being the main subject. Furthermore, our

publisher thought this was the best arrangement.

EM: What was the most striking thing you learned in the process of writing the book?

Frerichs: We eventually understood all aspects of how cholera came to Haiti and following an explosive and seemingly simultaneous phase in Artibonite River

communities, then spread throughout the country. Making these discoveries was standard practice for an epidemiologist versed in field and web research,

requiring some digging, but nothing too far out of the ordinary. What took more digging was understanding the unusual reactions of UN and CDC officials,

adding dark clouds to what should have been a clear-lighted investigation. As smart people misled, the obfuscating paths required major unraveling, presented

both in the book and in a supplemental website of visuals at www.deadlyriver.com.

EM: What is a good short statement of your main conclusion after writing the book?

Frerichs: Outbreak investigations always involve finding out what took place, identifying the source and understanding the disease spread. This information is

then used both for control programs and for prevention of future outbreaks. The cholera outbreak in Haiti was no different. When investigators were unable or

unwilling to identify the source, control programs in Haiti suffered, going in multiple directions without fundamental understanding, lacking total effectiveness.

EM: Is this the same as what you consider to be the main message from the book?

Frerichs: I like best a passage from the book’s introduction:

“What this book offers is an in-depth portrait of how scientific investigation is conducted when it is done right. It explores a quest for scientific truth and

dissects a scientific disagreement involving world-renowned cholera experts who find themselves embroiled in turmoil in a poverty-stricken country. It

describes the impact of political maneuvering by powerful organizations such as the United Nations and its peacekeeping troops in Haiti, as well as by the

World Health Organization (WHO) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In so doing, it raises issues about how the world’s wealthy

nations and international institutions respond when their interests clash with the needs of the world’s most vulnerable people. In an era when there is more

focus than ever before on global and population health, the story poses critical questions and offers insights not only about how to eliminate cholera in Haiti but

about how nations and international organizations such as the UN, WHO, and CDC deal with deadly emerging infectious diseases.”

EM: Has the link to the Nepalese peacekeepers been conclusively established beyond a shadow of a doubt? If not, how would you describe the strength of

the evidence pointing to them as the source?

Frerichs: Much of the evidence was presented in Piarroux’s first article in Emerging Infectious Diseases (1) and in the molecular article of Hendriksen et al

in MBio (2). The recent work of others and additional map graphics were added and summarized in Clinical Microbiology and Infection strengthening the case

all the more (3). These three articles provided sufficient evidence of Nepalese peacekeepers as the source for most scientific readers, leaving only a

few diehard skeptics.

The origin evidence is now established beyond a shadow of a doubt, at least in my eyes. Keep in mind, however, that the evidence we presented has not, and

likely will not, be presented in a court of law or face a trial by jury. Instead, the evidence in its totality is there for reputable scientists to consider. Neither

Piarroux nor I have heard any plausible alternative explanations, and doubt that any will be forthcoming, at least not ones that will stand the test of scientific

evidentiary scrutiny.

EM: What are the main reasons why you think epidemiologists will enjoy or benefit from reading the book.

Frerichs: What is not to like when you have a good medical detective story with flawed agencies and a dramatic power imbalance, presented in an exotic

setting; a French epidemiologist of high character, courage and grit; and a coverup by unlikely persons and organizations who imply they are following a higher

good, but instead are deluding the very people they purport to help, thereby diminishing themselves and losing trust?

I have had quite a literary journey with this book, now going on for five years. I hope your readers will find it of interest and value the contents, including of

course the website with visuals where the damning evidence is made more plain at: www.deadlyriver.com.

Sources:

(1) Piarroux, Renaud, Robert Barrais, Benoît Faucher, Rachel Haus, Martine Piarroux, Jean Gaudart, Roc Magloire, and Didier Raoult. “Understanding the

Cholera Epidemic, Haiti.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 17, no. 7 (2011): 1161–68

(2) Hendriksen, Rene S., Lance B. Price, James M. Schupp, John D. Gillece, Rolf S. Kaas, David M. Engelthaler, Valeria Bortolaia, Talima Pearson, Andrew E.

Waters, Bishnu Prasa Upadhyay, Sirjana Devi Shrestha, Shailaja Adhikari, Geeta Shakya, Paul S. Keim and Frank M. Aarestrup. “Population Genetics of

Vibrio cholerae from Nepal in 2010: Evidence on the Origin of the Haitian Outbreak.” MBio 2, no. 4 (2011): e00157-11.

(3) (Frerichs, Ralph R., Paul S. Keim, Robert Barrais, and Renaud Piarroux. “Nepalese Origin of Cholera Epidemic in Haiti.” Clinical Microbiology and Infection

18, no. 6 (2012): E158–163.

Epidemiologist Knighted in French Legion of Honor for Work on Cholera in Haiti

Source: Epidemiology Monitor 38(4), April 2017.

French officials announced earlier this month that epidemiologist Renaud Piarroux has been selected for the Legion of Honor, the highest French order of

merit for military and civil achievements. Since this is a rare honor for members of the profession, we sought to learn more about what Piarroux did to earn the

award and how he came to be nominated.

To get this information, we called on former UCLA epidemiologist Ralph R.Frerichs who has had a longstanding interest in John Snow’s work on cholera

in London and in Piarroux’s work on cholera in Haiti. He is the well-known creator of a website about John Snow and has more recently authored a book

entitled “Deadly River” about the introduction of

cholera into Haiti in 2010.

Following is Frerichs’s account of Piarroux’s work which earned him the Legion of Honor and an update on the recent progress being made to eradicate cholera

from Haiti after a long delay in mounting aggressive control efforts. Another story worth telling.

Special Report:

Knighted French Epidemiologist And Cholera Elimination in Haiti

By Ralph R. Frerichs

When cholera first appeared in Haiti in October 2010, there was scant interest in CDC or PAHO in investigating how this never-before-seen disease had made

its entrance. Instead, the two international institutions were dealing with treatment and care, assisting the overwhelmed Haitian society in addressing the

epidemic. Wanting immediate answers, the Haitian government, with the help of the French embassy in Port-au-Prince, reached out to Marseille-based

epidemiologist Renaud Piarroux. A short while later, his three-week investigation began.

Included in his findings was that cholera was brought to Haiti by United Nations peacekeepers from Nepal, starting an epidemic via a sewage spill into the

great river serving Haiti’s breadbasket. It then quickly spread throughout the country. Given the image and power of the United Nations, the apparent

indifference of the United States, the counter theories of other scientists, and even a critique in The Lancet Infectious Diseases (1), Piarroux’s findings of

UN involvement in the origin were not immediately believed or supported.

But after six years of additional field research, including development of a rapid response elimination strategy, Piarroux learned in April 2017

that he had been nominated for the highest civilian award offered in France, Au grade de chevalier in the Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur, or

knighthood in the National Order of the Legion of Honor.

Since its beginning, the Haiti epidemic has officially tallied 806,000 cholera cases and 9,500 deaths, the largest on-going cholera epidemic in the world.

Moreover, the United Nations has been severely criticized by legal and human rights groups for refusing a full apology and legal accountability for bringing

cholera to Haiti.

Nomination

How did Piarroux’s knighthood honor happen? In late 2016, Bernard Meunier, President of the French Academy of Sciences, read Deadly River: Cholera and

Cover-up in Post-Earthquake Haiti (Cornell University Press, 2016). The book told of Piarroux’s discoveries and actions, written in close collaboration with the

Frenchman, providing an insider’s view of the workings and thoughts of a medical epidemiologist, more public health professional and scientist than politician.

Meunier contacted me in November 2016, thanking me for writing the “well-documented book,” and noted, “truth is coming slowly while complex organizations

are fighting for their own survival, rather than tending to their duties.” Meunier learned more of Piarroux’s 30-year career and on-going efforts and

achievements in Haiti via research articles and the book epilogue at www.deadlyriver.com. In the coming months he submitted Piarroux’s name as a candidate

for knighthood in the Legion of Honor, formally accepted and officially posted on April 14, 2017 (2).

Background

As noted in Deadly River, when cholera in Haiti began, Piarroux was the department chief of the laboratory of parasitology and medical mycology at academic

Hôpital de la Timone in Marseille, France, as well as a professor at the medical school of Université d’Aix-Marseille. Through his service on humanitarian

missions in Afghanistan, Comoros, Honduras, Ivory Coast, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and his Ph.D. studies in microbiology and tropical

medicine, Piarroux had developed an interest in and a deep understanding of how cholera spreads through regions and communities — and of how epidemics

can be controlled and even eliminated. In 1999, the Médecins du Monde team he was leading actually eliminated cholera from Grande Comore, the largest

island in the Comoros nation off Africa’s east coast. But it was the African country of Madagascar, an island nation similar in many ways to Haiti, which offered

the best example of a cholera elimination strategy.

Example of Elimination in Madagascar

Cholera had come to Madagascar in 1999 after decades of absence. The disease plagued the country for three years and was then eliminated. Early on, local

health efforts had resorted to several control efforts, including a reporting system to identify suspicious cases and deaths, immediate treatment (including

intravenous rehydration), public education, and disinfection of houses. Mass immunization was never part of the weaponry.

Piarroux and his Haitian team reasoned that the pathogenic form of Vibrio cholerae would not become rooted in the Haitian environment independent of human amplification, and that with the

quick treatment of existing cases, a rapid response approach similar to that in Madagascar could be effective in Haiti. They developed the method which

featured rapid case finding and treatment using a map-based surveillance system, and treatment, education and water purification tablets issued to those

living in surrounding households to interrupt further spread.

Intervention Implementation in Haiti

Following local turmoil and management problems, the rapid response elimination effort in Haiti slowed for a while but then gathered steam following

Hurricane Matthew in October 2016. UNICEF had become a major supporter of the effort, yet as documented in a recent report (3), the number of rapid

response teams throughout the nation in early 2016 had dwindled to 32. They increased the number to 47 just prior to Hurricane Matthew, when cholera had

again exploded in the southwestern region of the country.

In the weeks that followed, 41 additional rapid response teams were mobilized, bringing the national number to 88. The epidemic peaked at over 1,400

suspected cholera cases per week immediately after the hurricane but then dramatically declined, aided a few weeks later by a limited one-dose (of a two-

dose vaccine) immunization program in the hardest hit area.

By the end of the sixth week in 2017, the number of weekly cases had been reduced to nearly 200 and according to government statistics, there were only a

handful of deaths.(4) The collaborative elimination effort of Piarroux and his Haitian colleagues continues. But like John Snow in the mid-1800s, it appears that

they have found their pump handle, hopefully leading to the end of Haiti’s epidemic.

[Frerichs note, 2025]: Cholera was eliminated from Haiti since the end of January, 2019. After being free of cholera for three years, the World Health Organization was to declare Haiti as "cholera free." At the Haiti Technical Conference

on Cholera Elimination in mid-February, 2022, the UN Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed told the audience that Haiti “will be the first country in modern times to

[eliminate cholera] following a large-scale outbreak. Haiti’s efforts have made it an example for the world.”(5) On September 23, 2022 (3 years and 7 months since the last confirmed case), the Haitian Ministry of Public Health and Population reported two new cholera cases, ending the elimination declaration.(6) At around the same time, gang activity had increased dramatically, cholera became rampant in the prison in the capitol city of Port-au-Prince, followed by a prison break.(7). Cholera exploded and again became epidemic in the country. The role of gangs in restarting the epidemic as a bioterrorism activity to destabilize the country has not been officially investigated. For additional details of bioterrorism hypothesis offered by Frerichs and Piarroux, click here and view slides 9-14.(8)]

Sources

1. Editorial, “As Cholera Returns to Haiti, Blame is Unhelpful.” Lancet Infectious Diseases, Vol. 10, no. 12 (2010): 813.

2. LeClerc J-M. "Légion d’honneur," Le Figaro, April 17, 2017.

3. UNICEF, Haiti Humanitarian Situation Report, 2017-02, March 7, 2017.

4. Ministere Sante Publique et de La Population (MSPP), Direction d’Epidémiologie de Laboratoire et de Recherches (DELR). Rapport du Réseau National de

Surveillance, Sites Choléra. 6ème Semaine Epidémiologique, 2017.

5. World Report. Eliminating Cholera in Haiti. The Lancet, Vol 139, May 21, 2022, pp. 1928-29.

6. Ocasio DV et al, Cholera Outbreak — Haiti, September 2022–January 2023. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 72(2), January 13, 2023.

7. Viaud L et al, A Cholera Outbreak in a Haitian Prison Threatens to Kill Hundreds in a Few Days.The Nation, October 11, 2022.

8. Frerichs RR. Deadly River website at www.deadlyriver.com, Epilogue 6, Slides 9-14, April-May, 2023.

Click to continue to Stream 5 - l: Current Cholera Information and Implications of Snow

Click to continue to Stream 5 - l: Current Cholera Information and Implications of Snow