Stream 2- Broad Street Pump Outbreak

a: Overview and Part 2 of John Snow's 1855 Book, Map 1

OVERVIEW

A well-written summary by Judith Summers of the 1854 cholera outbreak in the Soho neighborhood of London.

Source: Summers, Judith. Soho -- A History of London's Most Colourful Neighborhood, Bloomsbury, London, 1989 (pp. 113-117).

By the middle of the 19th century,Soho had become an insanitary place of cow-sheds, animal droppings, slaughterhouses, grease-boiling dens and primitive, decaying sewers. And underneath the floorboards of the overcrowded cellars lurked something even worse -- a fetid sea of cesspits as old as the houses, and many of which had never been drained. It was only a matter of time before this hidden festering time-bomb exploded. It finally did so in the summer of 1854.

When a wave of Asiatic cholera first hit England in late 1831, it was thought to be spread by "miasma in the atmosphere." By the time of the Soho outbreak 23 years later, medical knowledge about the disease had barely changed, though one man, Dr John Snow, a surgeon [specializing in anesthesiologist] and pioneer of the science of epidemiology, had recently published a report speculating that it was spread by contaminated water -- an idea with which neither the authorities nor the rest of the medical profession had much truck. Whenever cholera broke out -- which it did four times between 1831 and 1854 -- nothing whatsoever was done to contain it, and it rampaged through the industrial cities, leaving tens of thousands dead in its wake. The year 1853 saw outbreaks in Newcastle and Gateshead as well as in London, where a total of 10,675 people died of the disease. In the 1854 London epidemic the worst-hit areas at first were Southwark and Lambeth. Soho suffered only a few, seemingly isolated, cases in late August. Then, on the night of the 31st, what Dr Snow later called "the most terrible outbreak of cholera which ever occurred in the kingdom" broke out.

It was as violent as it was sudden. During the next three days, 127 people living in or around Broad Street died. Few families, rich or poor, were spared the loss of at least one member. Within a week, three-quarters of the residents had fled from their homes, leaving their shops shuttered, their houses locked and the streets deserted. Only those who could not afford to leave remained there. It was like the Great Plague all over again.

By 10 September, the number of fatal attacks had reached 500 and the death rate of the St Anne's, Berwick Street and Golden Square subdivisions of the parish had risen to 12.8 per cent -- more than double that for the rest of London. That it did not rise even higher was thanks only to Dr John Snow.

Snow lived in Frith Street [actually he had left his Frith Street home in 1852 and moved to nearby 18 Sackville Street], so his local contacts made him ideally placed to monitor the epidemic which had broken out on his doorstep. His previous researches had convinced him that cholera, which, as he had noted, "always commences with disturbances of the functions of the alimentary canal," was spread by a poison passed from victim to victim through sewage-tainted water; and he had traced a recent outbreak in South London to contaminated water supplied by the Vauxhall Water Company -- a theory that the authorities and the water company itself were, not surprisingly, reluctant to believe. Now he saw his chance to prove his theories once and for all, by linking the Soho outbreak to a single source of polluted water.

From day one he patrolled the district, interviewing the families of the victims. His research led him to a pump on the corner of Broad Street and Cambridge Street, at the epicenter of the epidemic. "I found," he wrote afterwards, "that nearly all the deaths had taken place within a short distance of the pump." In fact, in houses much nearer another pump, there had only been 10 deaths -- and of those, five victims had always drunk the water from the Broad Street pump, and three were schoolchildren who had probably drunk from the pump on their way to school.

Dr Snow took a sample of water from the pump, and, on examining it under a microscope, found that it contained "white, flocculent particles." By 7 September, he was convinced that these were the source of infection, and he took his findings to the Board of Guardians of St James's Parish, in whose parish the pump fell.

Though they were reluctant to believe him, they agreed to remove the pump handle as an experiment. When they did so, the spread of cholera dramatically stopped. [actually the outbreak had already lessened for several days due to a fleeing population.]

At the end of September the outbreak was all but over, with the death toll standing at 616 Sohoites. But Snow's theories were yet to be proved. There were several unexplained deaths from cholera that did not at first appear to be linked to the Broad Street pump water -- notably, a widow living in West End, Hampstead, who had died of cholera on 2 September, and her niece, who lived in Islington, who had succumbed with the same symptoms the following day. Since neither of these women had been near Soho for a long time, Dr Snow rode up to Hampstead to interview the widow's son. He discovered from him that the widow had once lived in Broad Street, and that she had liked the taste of the well-water there so much that she had sent her servant down to Soho every day to bring back a large bottle of it for her by cart. The last bottle of water -- which her niece had also drunk from -- had been fetched on 31 August, at the very start of the Soho epidemic.

There were many other factors that led Snow to isolate the cause of the cholera to the Broad Street pump. For instance, of the 530 inmates of the Poland Street workhouse, which was only round the corner, only five people had contracted cholera; but no one from the workhouse drank the pump water, for the building had its own well. Among the 70 workers in a Broad Street brewery, where the men were given an allowance of free beer every day and so never drank water at all, there were no fatalities at all. And an army officer living in St John's Wood had died after dining in Wardour Street, where he too had drunk a glass of water from the Broad Street well.

Still no one believed Snow. A report by the Board of Health a few months later dismissed his "suggestions" that "the real cause of whatever was peculiar in the case lay in the general use of one particular well, situated at Broad Street in the middle of the district, and having (it was imagined) its waters contaminated by the rice-water evacuations of cholera patients. After careful inquiry," the report concluded, "we see no reason to adopt this belief."

So what had caused the cholera outbreak? The Reverend Henry Whitehead, vicar of St Luke's church, Berwick Street, believed that it had been caused by divine intervention, and he undertook his own report on the epidemic in order to prove his point. However, his findings merely confirmed what Snow had claimed, a fact that he was honest enough to own up to. Furthermore, Whitehead helped Snow to isolate a single probable cause of the whole infection: just before the Soho epidemic had occurred, a child living at number 40 Broad Street had been taken ill with cholera symptoms, and its nappies had been steeped in water which was subsequently tipped into a leaking cesspool situated only three feet from the Broad Street well.

Whitehead's findings were published in The Builder a year later, along with a report on living conditions in Soho, undertaken by the magazine itself. They found that no improvements at all had been made during the intervening year. "Even in Broad-street it would appear that little has since been done... In St Anne's-Place, and St Anne's-Court, the open cesspools are still to be seen; in the court, so far as we could learn, no change has been made; so that here, in spite of the late numerous deaths, we have all the materials for a fresh epidemic... In some [houses] the water-butts were in deep cellars, close to the undrained cesspool... The overcrowding appears to increase..." The Builder went on to recommend "the immediate abandonment and clearing away of all cesspools -- not the disguise of them, but their complete removal."

Nothing much was done about it. Soho was to remain a dangerous place for some time to come.

ON THE MODE OF COMMUNICATION OF CHOLERA, PART 2

This second edition of John Snow's book, issued in 1855 three years before his death, is the historical treatise for which Snow is most famous in epidemiology. Included here is the second part of the book, pages 38-55, that addresses the Broad Street Pump Outbreak. To peruse the138 page book in its entirety, click on "JS Cholera Book" in the navbar at the top of each page.

Source: Snow, John. On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, 2nd Edition, London: John Churchill, New Burlington Street, England, 1855, pp. 38-55.

Contents of Part 2, pages 38-55

Instances of the communication of cholera through the medium of polluted water in the neighborhood of Broad Street, Golden Square

Instances of the communication of cholera through the medium of polluted water at Hampton West End (the water being carried from Broad Street)

Explanation of the Map showing the situation of the deaths in and around Broad Street, Golden Square

Table of attacks and deaths near Golden Square

INSTANCES OF THE COMMUNICATION OF CHOLERA THROUGH THE MEDIUM OF POLLUTED WATER IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD OF BROAD STREET, GOLDEN SQUARE

The most terrible outbreak of cholera which ever occurred in this kingdom, is probably that which took place in Broad Street, Golden Square, and the adjoining streets, a few weeks ago. Within two hundred and fifty yards of the spot where Cambridge Street joins Broad Street, there were upwards of five hundred fatal attacks of cholera in ten days. The mortality in this limited area probably equals any that was ever caused in this country, even by the plague; and it was much more sudden, as the greater number of cases terminated in a few hours. The mortality would undoubtedly have been much greater had it not been for the flight of the population. Persons in furnished lodgings left first, then other lodgers went away, leaving their furniture to be sent for when they could meet with a place to put it in. Many houses were closed altogether, owing to the death of the proprietors; and, in a great number of instances, the tradesmen who remained had sent away their families: so that in less than six days from the commencement of the outbreak, the most afflicted streets were deserted by more than three-quarters of their inhabitants.

There were a few cases of cholera in the neighborhood of Broad Street, Golden Square, in the latter part of August; and the so-called outbreak, which commenced in the night between the 31st August and the 1st September, was, as in all similar instances, only a violent increase of the malady. As soon as I became acquainted with the situation and extent of this irruption of cholera, I suspected some contamination of the water of the much-frequented street-pump in Broad Street, near the end of Cambridge Street; but on examining the water, on the evening of the 3rd September, I found so little impurity in it of an organic nature, that I hesitated to come to a conclusion. Further inquiry, however, showed me that there was no other circumstance or agent common to the circumscribed locality in which this sudden increase of cholera occurred, and not extending beyond it, except the water of the above mentioned pump. I found, moreover, that the water varied, during the next two days, in the amount of organic impurity, visible to the naked eye, on close inspection, in the form of small white, flocculent particles; and I concluded that, at the commencement o the outbreak, it might possibly have been still more impure. I requested permission, therefore, to take a list, at the General Register Office, of the deaths from cholera, registered during the week ending 2nd September, in the subdistricts of Golden Square, Berwick Street, and St. Ann's, Soho, which was kindly granted. Eighty-nine deaths from cholera were registered, during the week, in the three subdistricts. Of these, only six occurred in the four first days of the week; four occurred on Thursday, the 31st August; and the remaining seventy-nine on Friday and Saturday. I considered, therefore, that the outbreak commenced on the Thursday; and I made inquiry, in detail, respecting the eighty-three deaths registered as having taken place during the last three days of the week.

On proceeding to the spot, I found that nearly all the deaths had taken place within a short distance of the pump. There were only ten deaths in houses situated decidedly nearer to another street pump. In five of these cases the families of the deceased persons informed me that they always sent to the pump in Broad Street, as they preferred the water to that of the pump which was nearer. In three other cases, the deceased were children who went to school near the pump in Broad Street. Two of them were known to drink the water; and the parents of the third think it probable that it did so. The other two deaths, beyond the district which this pump supplies, represent only the amount of mortality from cholera that was occurring before the irruption took place.

With regard to the deaths occurring in the locality belonging to the pump, there were sixty-one instances in which I was informed that the deceased persons used to drink the pump-water from Broad Street, either constantly ,or occasionally. In six instances I could get no information, owing to the death or departure of every one connected with the deceased individuals; and in six cases I was informed that the deceased persons did not drink the pump-water before their illness.

The result of the inquiry then was, that there had been no particular outbreak or increase of cholera, in this part of London, except among the persons who were in the habit of drinking the water of the above-mentioned pump-well.

I had an interview with the Board of Guardians of St. James's parish, on the evening of Thursday, 7th September, and represented the above circumstances to them. In consequence of what I said, the handle of the pump was removed on the following day.

Besides the eighty-three deaths mentioned above as occurring on the three last days of the week ending September 2nd, and being registered during that week in the sub-districts in which the attacks occurred, a number of persons died in Middlesex and other hospitals, and a great number of deaths which took place in the locality during the last two days of the week, were not registered till the week following. The deaths altogether, on the 1st and 2nd of September, which have been ascertained to belong to this outbreak of cholera, were one hundred and ninety-seven; and many persons who were attacked about the same time as these, died afterwards. I should have been glad to inquire respecting the use of the water from Broad Street pump in all these instances, but was engaged at the time in an inquiry in the south districts of London, which will be alluded to afterwards; and when I began to make fresh inquiries in the neighborhood of Golden Square, after two or three weeks had elapsed, I found that there had been such a distribution of the remaining population that it would be impossible to arrive at a complete account of the circumstances. There is no reason to suppose, however, that a more extended inquiry would have yielded a different result from that which was obtained respecting the eighty-three deaths which happened to be registered within the district of the outbreak before the end of the week in which it occurred.

The additional facts that I have been able to ascertain are in accordance with those above related; and as regards the small number of those attacked, who were believed not to have drank the water from Broad Street pump, it must be obvious that there are various ways in which the deceased persons may have taken it without the knowledge of their friends. The water was used for mixing with spirits in all the public houses around. It was used likewise at dining-rooms and coffee-shops. The keeper of a coffee-shop in the neighborhood, which was frequented by mechanics, and where the pump-water was supplied at dinner time, informed me (on 6th September) that she was already aware of nine of her customers who were dead. The pump-water was also sold in various little shops, with a teaspoonful of effervescing powder in it, under the name of sherbet; and it may have been distributed in various other ways with which I am unacquainted. The pump was frequented much more than is usual, even for a London pump in a populous neighborhood.

There are certain circumstances bearing on the subject of this outbreak of cholera which require to be mentioned. The Workhouse in Poland Street is more than three-fourths surrounded by houses in which deaths from cholera occurred, yet out of five hundred and thirty-five inmates only five died of cholera, the other deaths which took place being those of persons admitted after they were attacked. The workhouse has a pump-well on the premises, in addition to the supply from the Grand Junction Water Works, and the inmates never sent to Broad Street for water. If the mortality in the workhouse had been equal to that in the streets immediately surrounding it on three sides, upwards of one hundred persons would have died.

There is a Brewery in Broad Street, near to the pump, and on perceiving that no brewer's men were registered as having died of cholera, I called on Mr. Huggins, the proprietor. He informed me that there were above seventy workmen employed in the brewery, and that none of them had suffered from cholera, -- at least in a severe form, -- only two having been indisposed, and that not seriously, at the time the disease prevailed. The men are allowed a certain quantity of malt liquor, and Mr. Huggins believes they do not drink water at all; and he is quite certain that the workmen never obtained water from the pump in the street. There is a deep well in the brewery, in addition to the New River water.

At the percussion-cap manufactory, 37 Broad Street, where, I understand, about two hundred workpeople were employed, two tubs were kept on the premises always supplied with water from the pump in the street, for those to drink who wished; and eighteen of these workpeople died of cholera at their own homes, sixteen men and two women.

Mr. Marshall, surgeon, of Greek Street, was kind enough to inquire respecting seven workmen who had been employed in the manufactory of dentists' materials, at Nos. 8 and 9 Broad Street, and who died at their own homes. He learned that they were all in the habit of drinking water from the pump, generally drinking about half-a-pint once or twice a day; while two persons who reside constantly on the premises, but do not drink the pump-water, only had diarrhea. Mr. Marshall also informed me of the case of an officer in the army, who lived at St. John's Wood, but came to dine in Wardour Street, where he drank the water from Broad Street pump at his dinner. He was attacked with cholera, and died in a few hours.

I am indebted to Mr. Marshall for the following cases, which are interesting as showing the period of incubation, which in these three cases was from thirty-six to forty-eight hours. Mrs. -----, of 13 Bentinck Street, Berwick Street, aged 28, in the eighth month of pregnancy, went herself (although they were not usually water drinkers), on Sunday, 3rd September, to Broad Street pump for water. The family removed to Gravesend (upper center) on the following day; and she was attacked with cholera on Tuesday morning at seven o'clock, and died of consecutive fever on 15th September, having been delivered. Two of her children drank also of the water, and were attacked on the same day as the mother, but recovered.

Dr. Fraser, of Oakley Square, kindly informed me of the following circumstance. A gentleman in delicate health was sent for from Brighton to see his brother at 6 Poland Street, who was attacked with cholera and died in twelve hours, on 1st September. The gentleman arrived after his brother's death, and did not see the body. He only stayed about twenty minutes in the house, where he took a hasty and scanty luncheon of rumpsteak, taking with it a small tumbler of brandy and water, the water being from Broad Street pump. He went to Pentonville, and was attacked with cholera on the evening of the following day, 2nd September, and died the next evening.

INSTANCES OF THE COMMUNICATION OF CHOLERA THROUGH THE MEDIUM OF POLLUTED WATER AT HAMPSTEAD WEST END (THE WATER BEING CARRIED FROM BROAD STREET)

Dr. Fraser also first called my attention to the following circumstances, which are perhaps the most conclusive of all in proving the connection between the Broad Street pump and the outbreak of cholera. In the "Weekly Return of Births and Deaths" of September 9th, the following death is recorded as occurring in the Hampstead district: "At West End, on 2nd September, the widow of a percussion-cap maker, aged 59 years, diarrhea two hours, cholera epidemics sixteen hours."

I was informed by this lady's son that she had not been in the neighborhood of Broad Street for many months. A cart went from Broad Street to West End every day, and it was the custom to take out a large bottle of the water from the pump in Broad Street, as she preferred it. The water was taken on Thursday, 31st August, and she drank of it in the evening, and also on Friday. She was seized with cholera on the evening of the latter day, and died on Saturday, as the above quotation from the register shows. A niece, who was on a visit to this lady, also drank of the water; she returned to her residence, in a high and healthy part of Islington, was attacked with cholera, and died also. There was no cholera at the time, either at West End or in the neighborhood where the niece died. Besides these two persons, only one servant partook of the water at Hampstead West End, and she did not suffer, or, at least, not severely. There were many persons who drank the water from Broad Street pump about the time of the outbreak, without being attacked with cholera; but this does not diminish the evidence respecting the influence of the water, for reasons that will be fully stated in another part of this work.

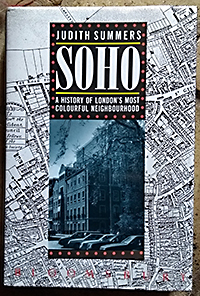

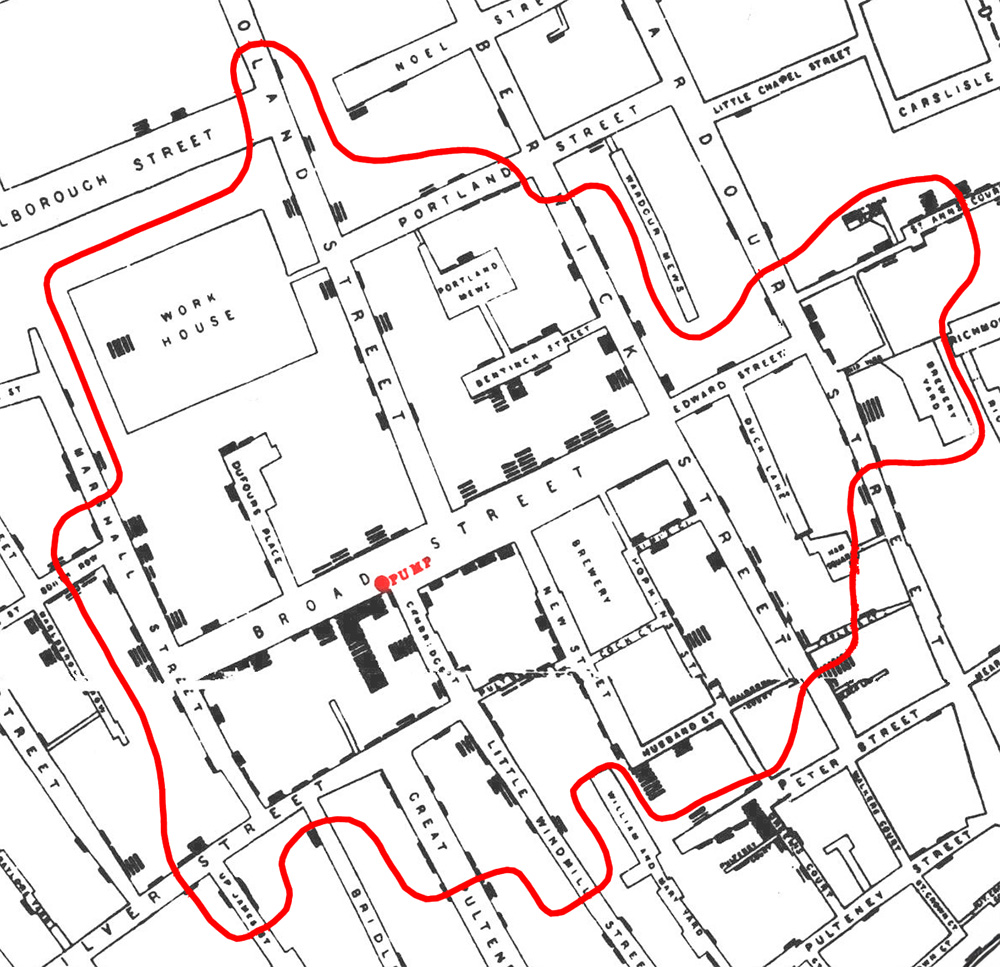

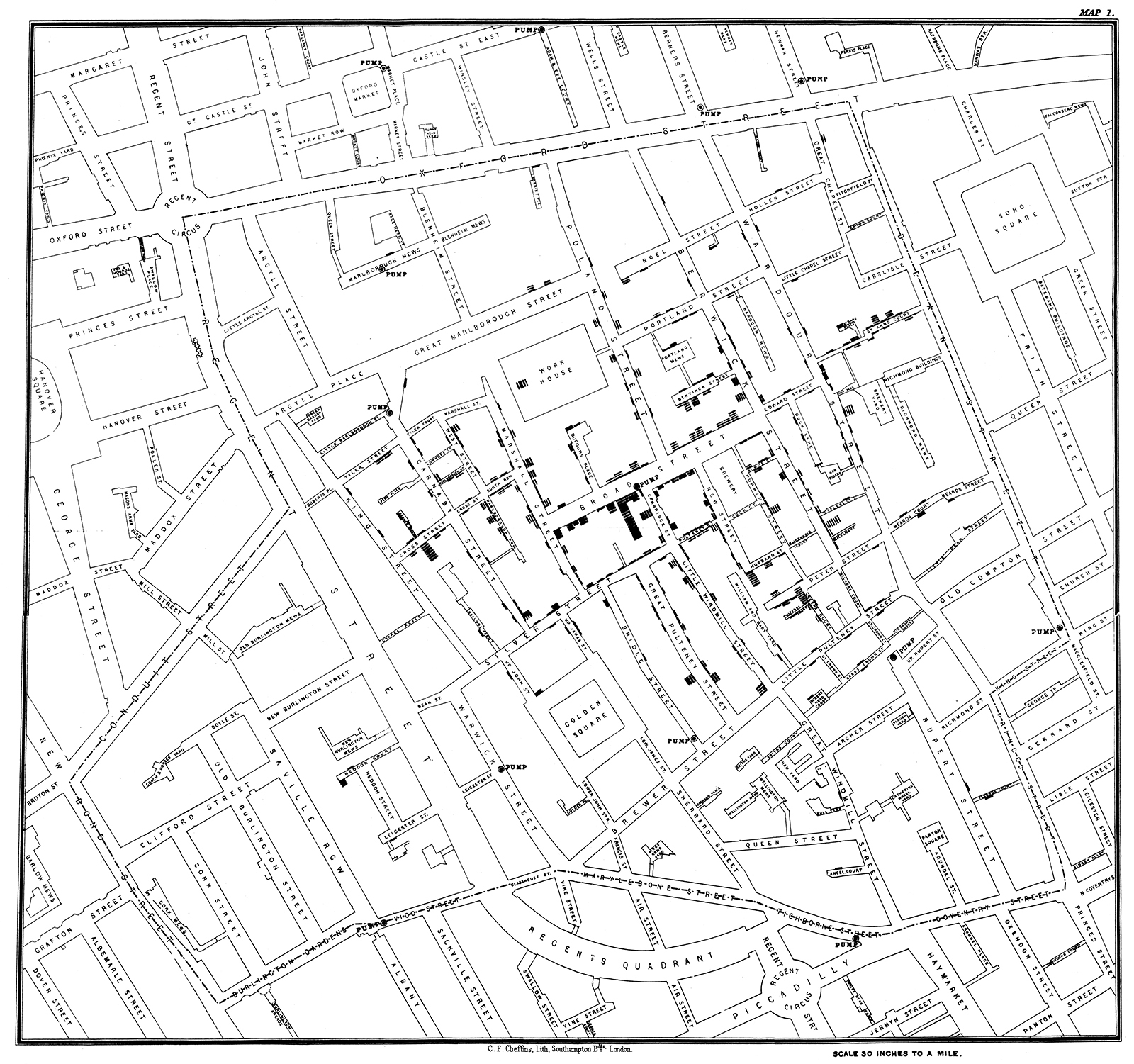

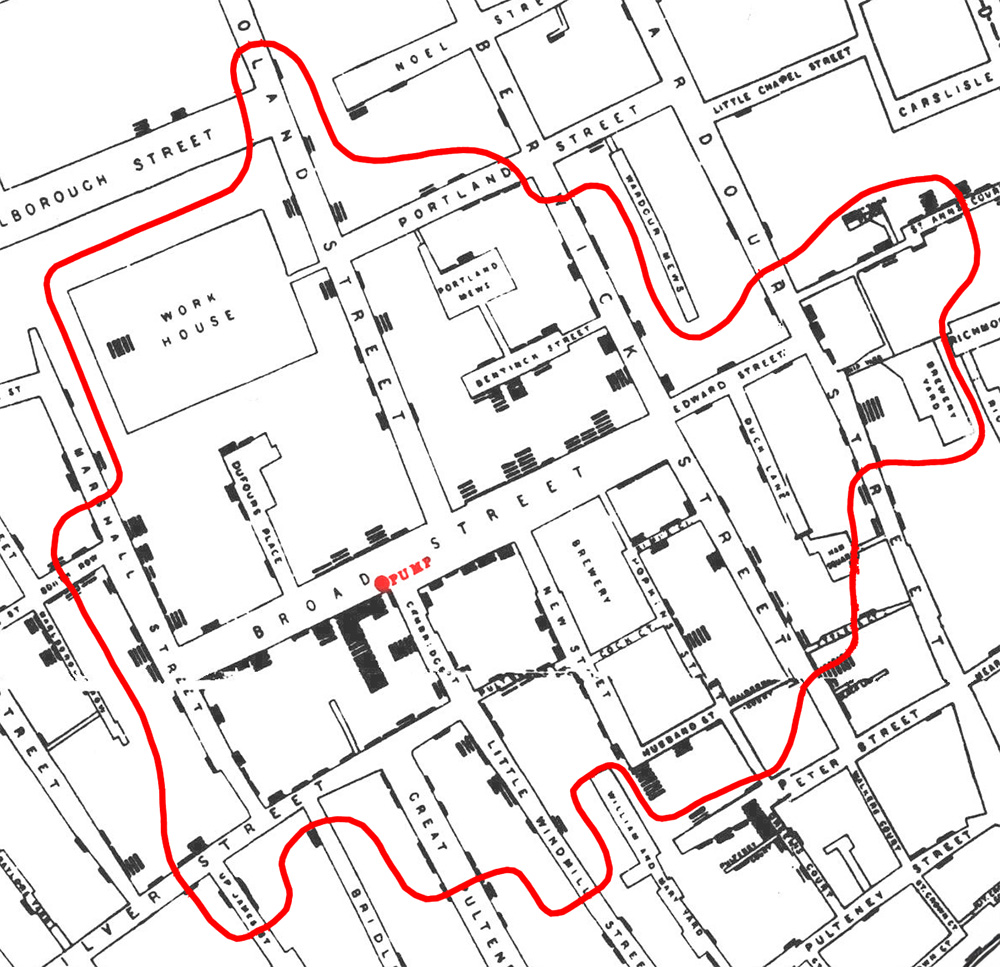

EXPLANATION OF THE MAP SHOWING THE SITUATION OF THE DEATHS IN AND AROUND BROAD STREET, GOLDEN SQUARE

The deaths which occurred during this fatal outbreak of cholera are indicated in the accompanying map, as far as I could ascertain them.

MAP I

Click for Snowmap1.pdf (5.7 mb)

Click for Snowmap1.pdf (5.7 mb)

Click for Snowmap1_HR.pdf (51.2 mb)

Click for Snowmap1_HR.pdf (51.2 mb)

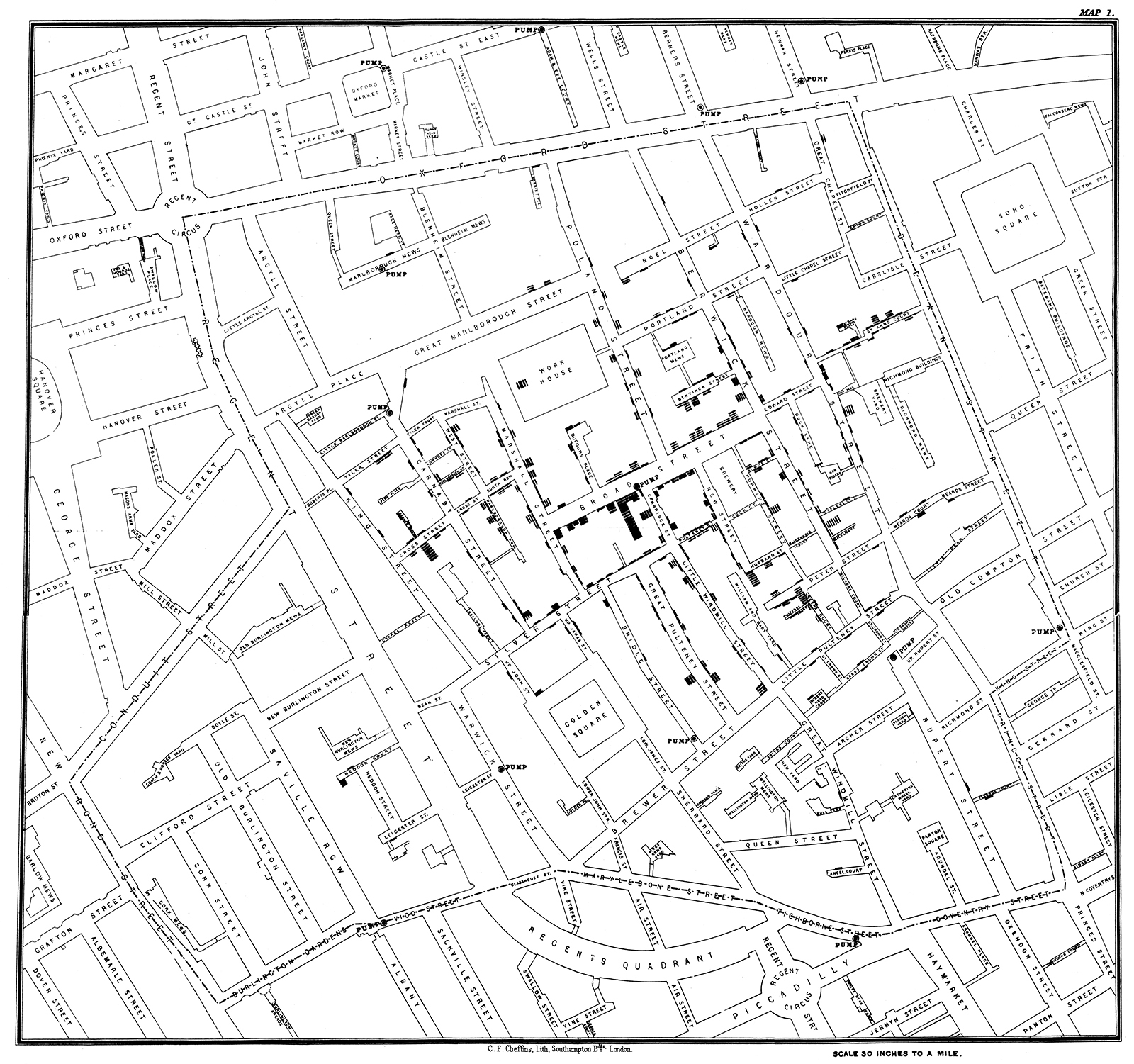

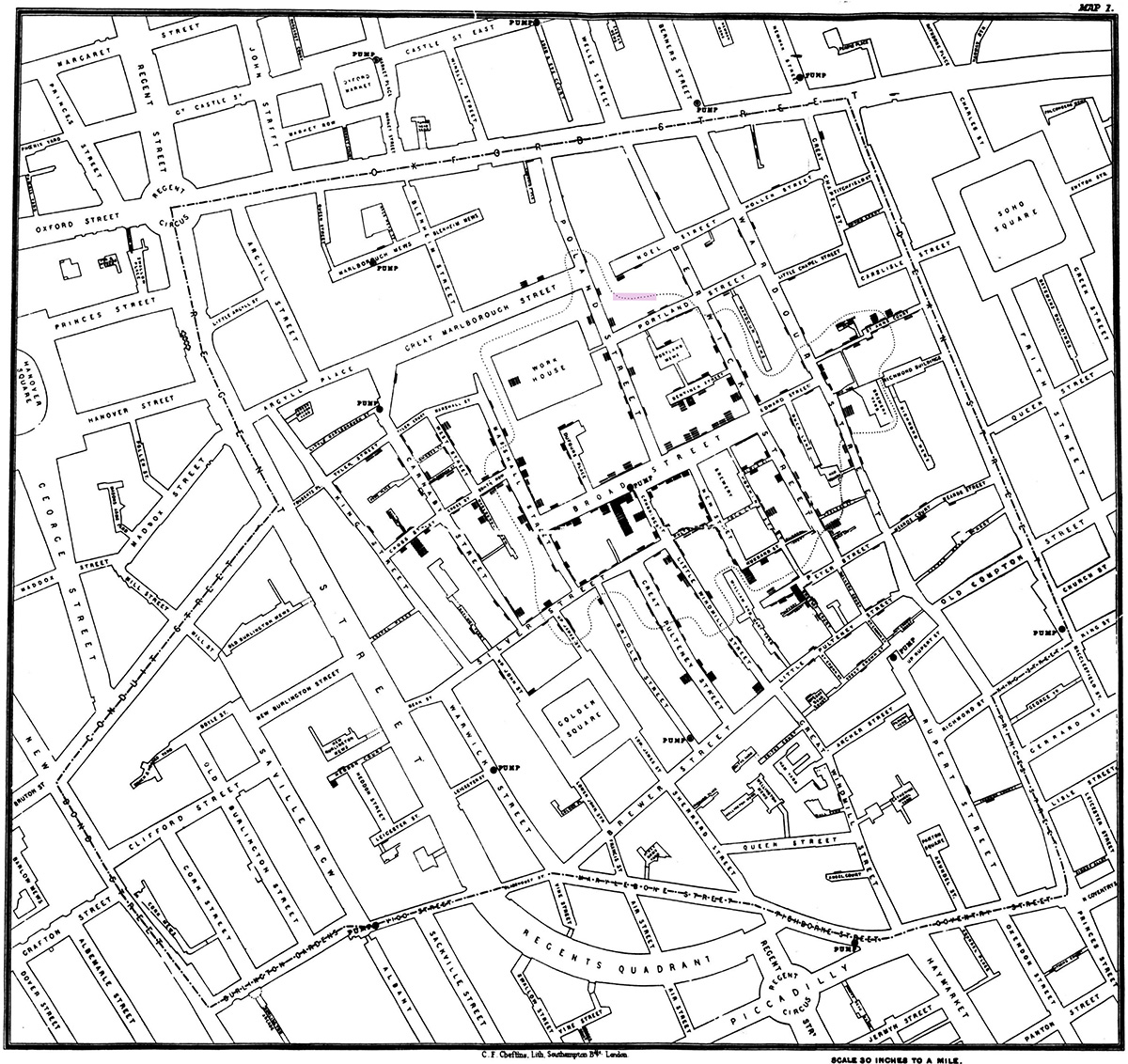

MAP 1 - An Aside

MAP 1 - An Aside

While not in Snow's 1855 book, he did modify Map 1 at the time for a meeting wth the Cholera Inquiry Committee (CIC). Included was presentation of a version of Map 1 with stippled lines to reflect walking distances to the Broad Street Pump and other nearby pumps. Specifically, Snow wrote...

The pump in Broad Street is indicated on the map, as well as all the surrounding pumps to which the public had access at the time of the outbreak of Cholera. The water of the pump in Marlborough Street, at the end of Carnaby Street, was so impure that many persons avoided using it. I found that the persons who died near this pump in the beginning of September had taken water from the Broad Street pump. The inner dotted [stippled] line on the map shows the various points which have been found by careful measurement to be at an equal distance by the nearest road from the pump in Broad Street and the surrounding pumps. If allowance be made for the circumstance just mentioned respecting the pump in Marlborough Street, it will be observed that the deaths either very much diminish, or cease altogether, at every point where it becomes decidedly nearer to go to another pump than to the one in Broad Street. At these points, I ascertained that the peope did generally go to the pump that was nearer. [the pink spot is a repair in the map due to a tear].

Source: Snow, J. “Dr. Snow’s Report,” in Cholera Inquiry Committee, Report on the Cholera Outbreak in the Parish of St. James, Westminster, presented on 12 December 1854, publshed in CIC report, August 1855.

A clearer view of Snow's dotted lines appear here, drawn in red.

Source: Castro AM, Cuaderna de Cultura Cientifica, Fronteras, April 11, 2019.

Map 1 and Map 1a

Map 2

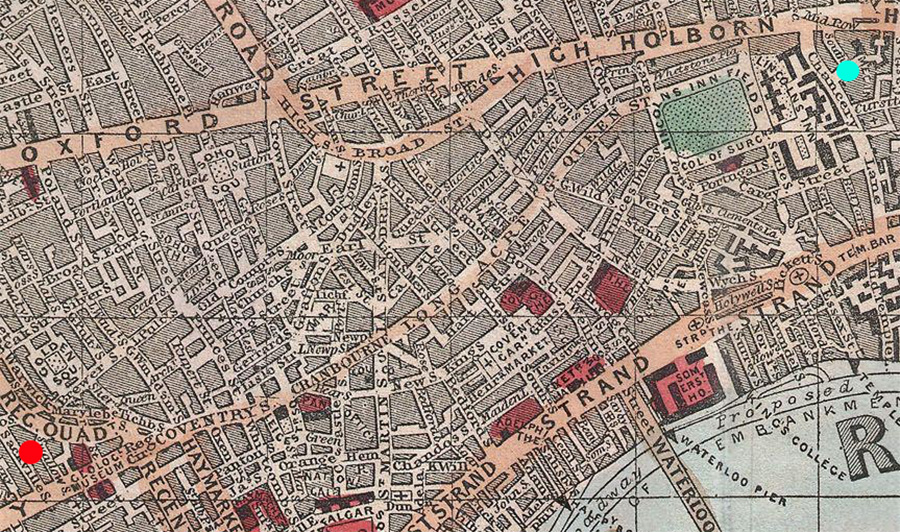

Snow's home  , Cheffins' office

, Cheffins' office

Source: Reynolds's Map of Modern London Divided into Quarter-Mile Sections for Measuring Distances, 1862.

Both version of Map 1 were drawn for John Snow by Charles Frederick Cheffins (1807–1861) at 9 and 11 Southampton Buildings in the Holborn region of London. Cheffins' career had many facets, including being a mechanical draftsman, lithographer, cartographer, consulting engineer, and surveyor. Besides Snow's three maps (two versions of Map 1 and one version of Map 2 - the "Grand Experiment" - featured in Snow's 1855 book), Cheffins published many maps, mainly depicting new railways, either proposed or being built.

End of Aside - Forward to 1854

End of Aside - Forward to 1854

There are necessarily some deficiencies, for in a few of the instances of persons who died in the hospitals after their removal from the neighborhood of Broad Street, the number of the house from which they had been removed was not registered. The address of those who died after their removal to St. James's Workhouse was not registered; and I was only able to obtain it, in a part of the cases, on application at the Master's Office, for many of the persons were too ill, when admitted, to give any account of themselves. In the case also of some of the work people and others who contracted the cholera in this neighborhood, and died in different parts of London, the precise house from which they had removed is not stated in the return of deaths. I have heard of some persons who died in the country shortly after removing from the neighborhood of Broad Street; and there must, no doubt, be several cases of this kind, that I have not heard of. Indeed, the full extent of the calamity will probably never be known. The deficiencies I have mentioned, however, probably do not detract from the correctness of the map as a diagram of the topography of the outbreak; for, if the locality of the few additional cases could be ascertained, they would probably be distributed over the district of the outbreak in the same proportion as the large number which are known. The dotted line on the map surrounds the sub-districts of Golden Square, St. James's, and Berwick Street, St. James's, together with the adjoining portion of the sub-district of St. Anne, Soho, extending from Wardour Street to Dean Street, and a small part of the sub-district of St. James's Square enclosed by Marylebone Street, Titchfield Street, Great Windmill Street, and Brewer Street. All the deaths from cholera which were registered in the six weeks from 19th August to 30th September within this locality, as well as those of persons removed into Middlesex Hospital, are shown in the map [1] by a black line in the situation of the house in which it occurred, or in which the fatal attack was contracted. In addition to these the deaths of persons removed to University College Hospital, to Charing Cross Hospital, and to various parts of London, are indicated in the map, where the exact address was given in the "Weekly Return of Deaths," or, when I could learn it by private inquiry. The pump in Broad Street is indicated on the map, as well as all the surrounding pumps to which the public had access at the time.

It requires to be stated that the water of the pump in Marlborough Street, at the end of Carnaby Street, was so impure that many people avoided using it. And I found that the persons who died near this pump in the beginning of September, had water from the Broad Street pump. With regard to the pump in Rupert Street, it will be noticed that some streets which are near to it on the map, are in fact a good way removed, on account of the circuitous road to it. These circumstances being taken into account, it will be observed that the deaths either very much diminished, or ceased altogether, at every point where it becomes decidedly nearer to send to another pump than to the one in Broad Street. It may also be noticed that the deaths are most numerous near to the pump where the water could be more readily obtained. The wide open street in which the pump is situated suffered most, and next the streets branching from it, and especially those parts of them which are nearest to Broad Street. If there have been fewer deaths in the south half of Poland Street than in some other streets leading from Broad Street, it is no doubt because this street is less densely inhabited.

In some of the instances, where the deaths are scattered a little further from the rest on the map, the malady was probably contracted at a nearer point to the pump. A cabinet-maker, who was removed from Philip's Court, Noel Street, to Middlesex Hospital, worked in Broad Street. A boy also who died in Noel Street, went to the National school at the end of Broad Street, and having to pass the pump, probably drank of the water. A tailor, who died at 6, Heddon Court, Regent Street, spent most of his time in Broad Street. A woman, removed to the hospital from 10, Heddon Court, had been nursing a person who died of cholera in Marshall Street. A little girl, who died in Ham Yard, and another who died in Angel Court, Great Windmill Street, went to the school in Dufour's Place, Broad Street, and were in the habit of drinking the pump-water, as were also a child from Naylor's Yard, and several others, who went to this and other schools near the pump in Broad Street. A woman who died at 2, Great Chapel Street, Oxford Street, had been occupied for two days preceding her illness at the public washhouses near the pump, and used to drink a good deal of water whilst at her work; the water drank there being sometimes from the pump and sometimes from the cistern.

The limited district in which this outbreak of cholera occurred, contains a great variety in the quality of the streets and houses; Poland Street and Great Pulteney Street consisting in a great measure of private houses occupied by one family, whilst Husband Street and Peter Street are occupied chiefly by the poor Irish. The remaining streets are intermediate in point of respectability. The mortality appears to have fallen pretty equally amongst all classes, in proportion to their numbers. Masters are not distinguished from journeymen in the registration returns of this district, but, judging from my own observation, I consider that out of rather more than six hundred deaths, there were about one hundred in the families of tradesmen and other resident house-holders. One hundred and five persons who had been removed from this district died in Middlesex, University College, and other hospitals, and two hundred and six persons were buried at the expense of St. James's parish; the latter number includes many of those who died in the hospitals, and a great number who were far from being paupers, and would on any other occasion have been buried by their friends, who, at this time, were either not aware of the calamity or were themselves overwhelmed by it. The greatest portion of the persons who died were tailors and other operatives, who worked for the shops about Bond Street and Regent Street, and the wives and children of these operatives. They were living chiefly in rooms which they rented by the week.

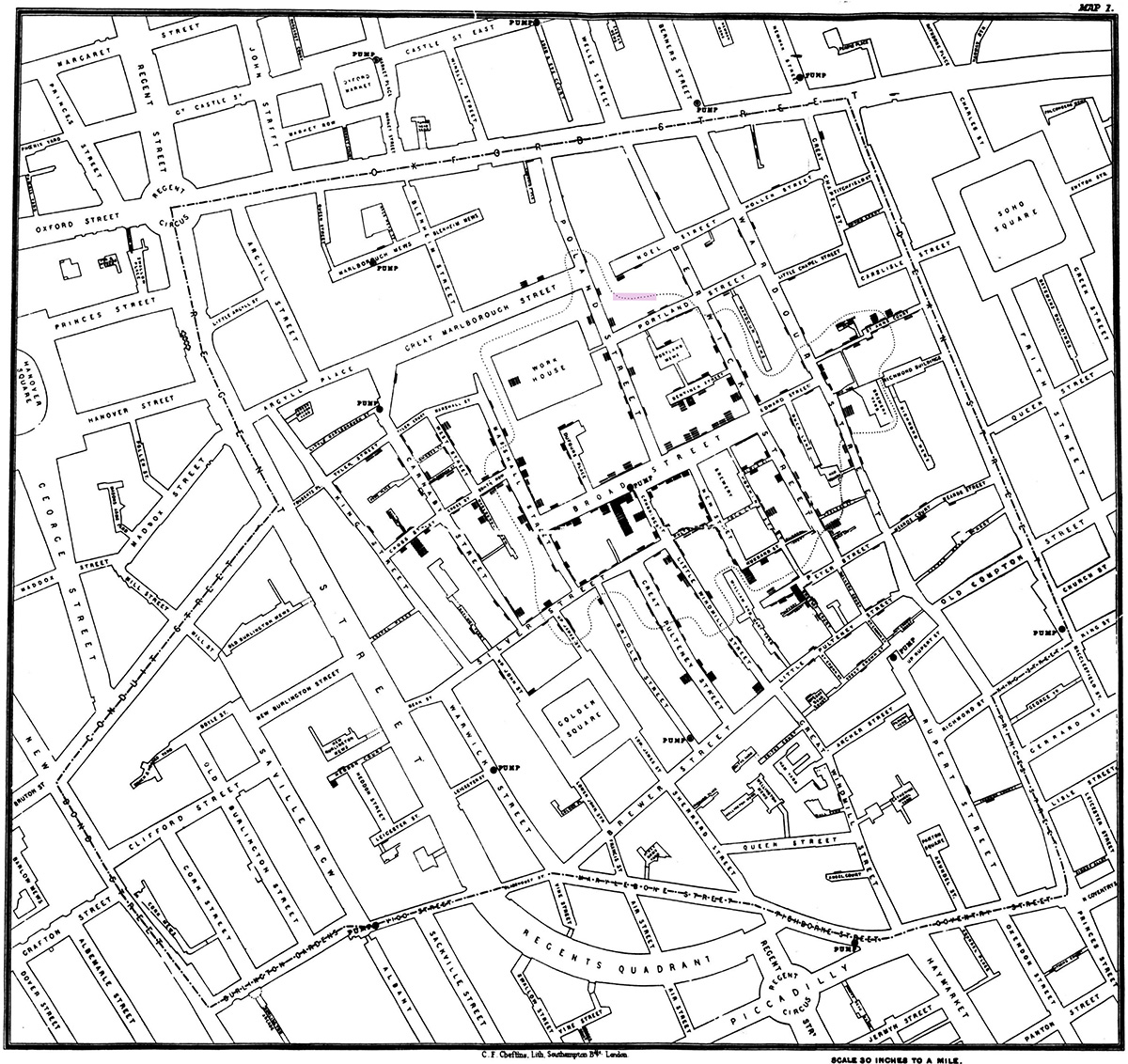

TABLE OF ATTACKS AND DEATHS NEAR GOLDEN SQUARE

The following table exhibits the chronological features of this terrible outbreak of cholera.

MAP 1 - An Aside

MAP 1 - An Aside

, Cheffins' office

, Cheffins' office

End of Aside - Forward to 1854

End of Aside - Forward to 1854