Letters of Remembrance

When John Snow died on June 16, 1858, his brother Thomas Snow was already there for a visit, ready to tend to the painful details of his early death. He met with a mortician, selected Brompton Cemetery, helped address his financial affairs, decided on a tombstone, and organised the family gathered for a gravesite vigil, including the burial, on June 21, 1858. His father had died earlier, as had one of his brothers. It is not clear who was able to attend.

Five days after the burial, The Lancet issue a four-line note of his passing, mentioning that he died from an attack of apoplexy at his home on June 16th, and briefly referenced his work on chloroform and other anesthetics. There was no mention of his seminal studies on cholera.

Three weeks went by before two two supportive letters appeared in The Lancet, a week apart, offering testimonial to Snow's special qualities and achievements.

The Lancet, July 17, 1858

The Late Dr. Snow

To the Editor of THE LANCET.

Sir, --- I trust that the profession will evince some public testimony towards the late Dr. John Snow. Who does not remember his frankness, his cordiality, his honesty, the absence of all disguise or affectation under an apparent off-hand manner. Her majesty the Queen has been deprived of the future valuable services of a trustworthy, well-deserving, much-esteemed subject, by his sudden death. The poor have lost in him a real friend in the hour of need.

I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

W. Hooper ATTREE

Bognor, Sussex, July, 1858.

Formerly House-Surgeon to the Middlesex Hospital

The Lancet, July 24, 1858

The Late Dr. Snow

To the Editor of THE LANCET.

Sir, --- Your correspondent, Mr. Attree, suggests a tribute to the memory of Dr. Snow for his amiable qualities; and well do I remember the happy and truthful expression contained in a testimonial to his merit, written by an eminent member of our profession, "that he possessed a temper which nothing could provoke." These qualities, no doubt, rendered him dear to all who had the happiness of knowing him; but it is due to him that both the profession and the public should be made aware of his great labors in the cause of sanitary science. I believe that since the days of Jenner no physician has rendered more important service to mankind than Dr. Snow.

When his doctrine respecting the mode in which cholera is communicated becomes comprehended by secretaries-of-state and generals commanding-in-chief, as is the household word "vaccination," then "outbreaks" of cholera -- that is, large numbers of persons attacked at once in a district (a phenomenon well known in the history of the disease) will become rare events.

If Dr. Snow ever inferred too much from the facts which he so laboriously collected, at least he perceived the fallacies of theory, propounded by Mr. Chadwick [Edwin Chadwick], which referred to fetid odors as the dwelling-place of cholera (an approximation, indeed, to the truth): he confidently asserted that stench is not pestiferous, as declared by Act of Parliament -- an opinion which is confirmed by the able paper of Dr. Barnes in your journal last week [Barnes R. The Lancet 2, 73, July 17, 1858]. Surely stinks are nuisances so intolerable that they require no argument or pseudo-theory for their suppression. Let them be remedied on their own very obvious grounds, and at any cost.

Now, although the important views embraced by Dr. Snow are very difficult to study properly, although an ardent mind may have led him to the adoption of some inferences not quite warranted by the facts, which will retard their progress; and although ephemeral criticism has been uniformly against him, yet I venture confidently to predict, that the facts which have been brought to light by his indefatigable industry will prove to posterity that he was by far the most important investigator of the subject of cholera who has yet appeared. His premature death may possibly accelerate the study of the views which he has so ingeniously advanced.

I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

J. G. FRENCH, F. R. C. S. [Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons]

Great Marlborough-street, July, 1858.

MORE ABOUT LETTER-WRITERS

William Hooper Attree (1817 - 1875) was the son of a prominent surgeon and was himself the surgeon for Don Miguel de Braganza, the former King of Portugal. His father, William Attree (1780 - 1846) was appointed as one of the original 300 Fellows of the Royal College of Surgeons. A few years later, the father lost his wife in childbirth and then a year later, had his foot amputated. Despite these hardships, Attree senior continued and eventually was the Surgeon Extraordinary to two Kings: George IV and William IV. Later in life following his successful medical career, son W. Hooper Attree became the Warden (i.e., the Head) of Sackville College in East Grinstead, England.

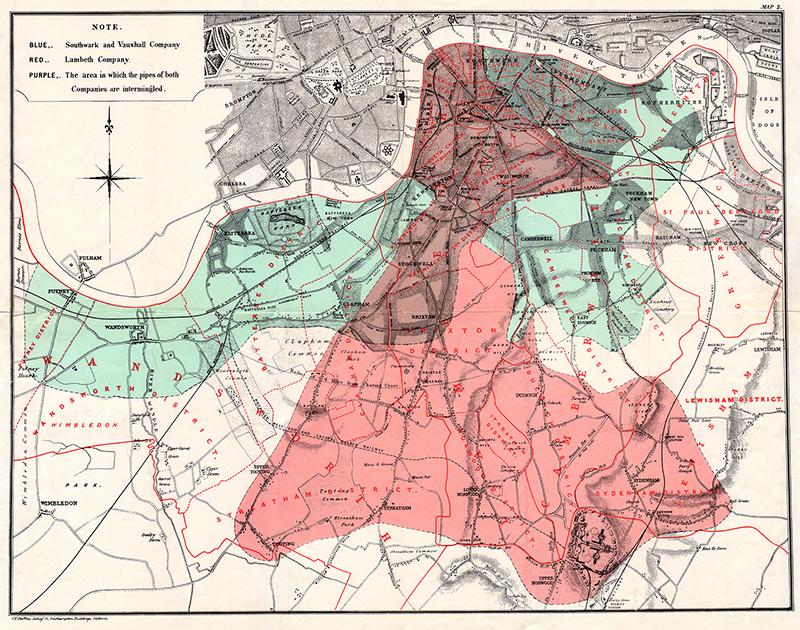

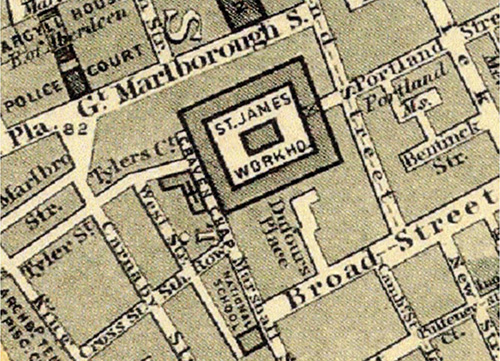

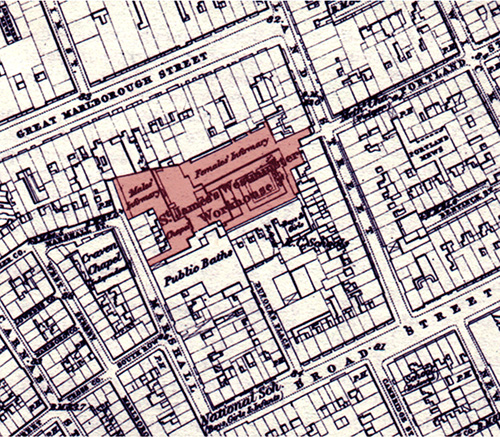

John George French (1804-1887) qualified as a doctor in 1826 and served as the medical officer of the St James's Workhouse in Poland Street (also referred to as the "Poland Street Workhouse") from 1830 until 1872. The 1862 map (below left), followed by an 1870 map (below right), shows the location of the workhouse by Great Marborough Street, although Poland Street is the site of the main entrance. Broad Street is just to the south. Besides living quarters, the workhouse contained a chapel, and male and female infirmaries.

Sources: Stanford's Library Map of London and its Suburbs. Published by Edward Stanford, 6, Charing Cross, London, February 15, 1862.; and Old Ordnance Survey Maps -- The West End, 1870.

French was granted Fellowship in the Royal College of Surgeons - the highest qualification - in 1852. He was a bachelor like Snow and had great affection for the people of the Soho district, tending to the poor with little financial reward. He and John Snow first worked together in 1849 when they tended to an abnormal labor in the Poland Street Workhouse. At that time, French disagreed with Snow's theory that cholera was a waterborne disease. Later, however, after the 1854 cholera outbreak decimated Soho, French changed his mind and joined John Snow in his views.

EXTENSIVE TESTIMONIAL

Years later, a detailed summary and analysis of John Snow's life was published by his friend and professional colleague, Sir Benjamin Richardson, (click for Stream 1 - e: Memoir of his friend Bejamin Ward Richardson).

BROTHER'S DEFENSE

Folowing the definitive isolation in pure culture of Vibrio cholerae by Robert Koch in 1884, John Snow's younger brother Thomas (1821-93) took umbrage with a letter that had appeared in The Times. Thomas Snow, then age 64, was vicar of Underbarrow in Cumbria, England, near Kendal. He wrote:

Source: "Propagation of cholera," The Times, 28 September 1885 [Ltr. to Ed.].

TO THE EDITOR OF THE TIMES:

Sir:--In a letter to the Times of the 21st of September, under the heading "Madrid--Main Sewers and Cholera," the writer says:-- "I have read theories propounded by undeniably able men as to the cause of fever and cholera; but upon reflection they have failed to convince me. I heard the late Dr. Snow on cholera excreta tainted water being necessary to the production of cholera. I, however, have seen that theory disproven on a great scale."

The late Dr. Snow never held such a theory and as that which is here ascribed to him. He did indeed, prove by a catena of incontrovertible facts that cholera was largely propagated by water thus tainted; but so far from maintaining that this condition was "necessary to the production of cholera," he devotes several pages of his book--"On the Mode of Communication of Cholera"--to the pointing out of modes of propagation othewise than by water.

I trust that, in justice to the memory of one who shortened his own life in his arduous labours for the preservation of the lives of others, you will allow me space for this correction of a serious apprehension with regard to his teaching.

I am, Sir, yours faithfully;

THOMAS SNOW. Underbarrow Parsonage, Kendal, Sept. 23.

A month later, Thoms Snow again commented about a letter in The Times that mentioned his brother.

Source: "Dr. Snow on the communication of cholera", The Times, 20 November 1885 [Ltr. to Ed.].

To the editor of the Times.

Sir,--The Times of the 13th November has a leading article [editorial] on the cholera in Spain, containing some references to the researches of my late brother, Dr. Snow; and I ask the favour of a brief space in the Times for a statement of the facts with regard to those references.

Your article says:--"It was only when the inhabitants of a court in Broad-street, during the London epidemic of 1854, were struck down in very large proportions, that the sagacity of the late Dr. Snow caught at the possibility of water being a common channel for the diffusion of the poison, and led him to institute observations for the purpose of confirming or disproving his hypothesis."

Dr. Snow prosecuted his researches and furnished abundant facts in confirmation of his theory, long before 1854. During the season of 1849 he published several pamphlets, wrote letters to the Times and the medical periodicals, maintaining the conclusions which are now universally accepted by the faculty. So far from the case of the Broad-street pump suggesting in 1854 the possibility of water being a common channel for the diffusion of the poison, the remarkable facts of this case were of the same character as those with which he had already become familiar. But in this case the facts took what may be called a dramatic form; and the immediate abatement of the cholera--when, on Dr. Snow's urgent appeal, the authorities removed the handle of the pump--was the means of bringing his theory before the notice of the general public, and hence the mistaken impression has arisen that his researches commenced with the case of the Broad-street pump.

I must strongly demur to the statement that "Dr. Snow had no opportunity of obtaining absolute proof of the soundness of his views." His work On the Mode of Communication of Cholera" (Churchill), published in 1855, and now lying before me, is crowded with specific facts, to the same purport and equally decisive with those which you quote from Mr. Netten Radcliffe's observations in 1866; and I have the testimony of distinguished London physicians to the fact that the outbreak in London in 1866--eight years after Dr. Snow's death--was held in check by the following of the light of his researches.

I am, Sir, yours faithfully,

Thos. Snow.

Underbarrow Parsonage, Kendal, Nov. 16.

The Times editor responded...

[Reverend Snow was correct that his brother's cholera theory and researches antedate the Golden Square outbreak. But, ironically, his explanation of the Broad Street pump episode shows that he has accepted the mis-perception that removal of the pump handle by the local authorities ended the local outbreak. In his previous letter to the Times he says that Snow's MCC2 lies open before him. If he had opened it before writing this letter and refreshed his memory of his brother's account, he would have noted that the outbreak was essentially over days before the handle was removed.

What is illuminating, however, about Rev. Snow's mistake is that he suggests that the mis-perception was commonplace among the general public. He does not mention Richardson's memoir from 1858, which would not have been widely known among the general public. PVJ.]

GRADUAL CHANGE OF HEART IN THE LANCET

Much has been written about John Snow in the many decades that followed his death. Yet in all that time, The Lancet never addressed the inappropriateness of the short obituary that Editor Thomas Wakley (1795–1862) authorized for publication in June 26, 1858. All this changed on Apri 13, 2013 when they published a revised obituary, reflecting views altered by historical reflection. The Lancet's new obituary will be present after the following section.

First will be another reflective article on Snow by academician and historian Stephanie Snow Ph.D., also published in The Lancet but in 2008, five years before the revised obituary.

JOHN SNOW: THE MAKING OF A HERO? (2008)

Source: Snow, S.J. John Snow: the making of a hero?, The Lancet, 372(9632), 22-23, July 5, 2008.

[Frerichs comment] I like this article because it is both informative and provocative. When Stephanie Snow added a question mark to the title of her article about John Snow, readers should known that they are getting an interesting point of view. After all, a hero as defined in the Oxford Dictionary is "a person who is admired for their courage, outstanding achievements, or noble qualities," quite an inclusive list. Snow certainly was a maverick in his time, having the "courage" of his convictions, whether over temperance, safe anesthesia, or out-of-favor epidemiological research on cholera. He indeed had "outstanding achievements," being notable in his era. The last attribute, however, of "noble qualities" is harder to judge, since there are only a few sources available on his views, personality and giving or caring nature. With that said, read on and decide if being a "hero" is an answered question.

Stephanie Snow is a Professor of Health, History and Policy at the University of Manchester in Manchester, England, and had written her Ph.D. thesis (University of Keele, 1995) on the life and work of John Snow, followed by a book, Blessed Days of Anaesthesia, 2009 (at right) that covers the early years of the profession, including the outrage stimulated by Queen Victoria's use of chloroform during the birth of Prince Leopold.

Professor Snow is distantly related to John Snow by marriage, being the wife of his great, great, great nephew. In 2017 on March 15th - the 204th anniversary of Snow's birth - she attended, along with her father-in-law Geoff Snow (John Snow's great, great nephew), a major memorial in York's North Street Gardens overlooking the River Ouse.

The memorial project arose from a collaboration between York Civic Trust, York Medical Society and the University of York, with support from the City of York Council, York Hospital and Yorkshire Water.

The art of medicine

John Snow: the making of a hero?

150 years ago last month, The Lancet published an obituary: "DR JOHN SNOW - This well-known physician died at noon on the 16th instant, at his house in Sackville-street, from an attack of apoplexy. His researches on chloroform and other anaesthetics were appreciated by the profession."

John Snow's death was sudden and early - he was only 45 years of age. Other obituaries and eulogies were more effusive. At the time of Snow's demise he was a successful anaesthetist whose expertise was widely sought by surgeons and patients, but his theory that cholera was spread through water was not broadly supported. Yet fast forward to the present and Snow has become an iconic figurehead across public health and epidemiology, as well as anaesthesia. The John Snow Society founded in 1993 with around 1500 members worldwide, promotes his life and works, and seeks to "provide a communication network for epidemiologists and those trained in the Snow tradition throughout the world". The Society organises annual lectures at which members re-enact the removal of the pump handle during the eponymous 1854 cholera outbreak in Broad Street, Soho, London, UK. It also produces Snow memorabilia and the Society recently introduced a walk in the footsteps of "the medical detective" through the streets of Soho, concluding at the John Snow pub - itself a peculiar memorial since he practised temperance. So how has Snow been made a hero?

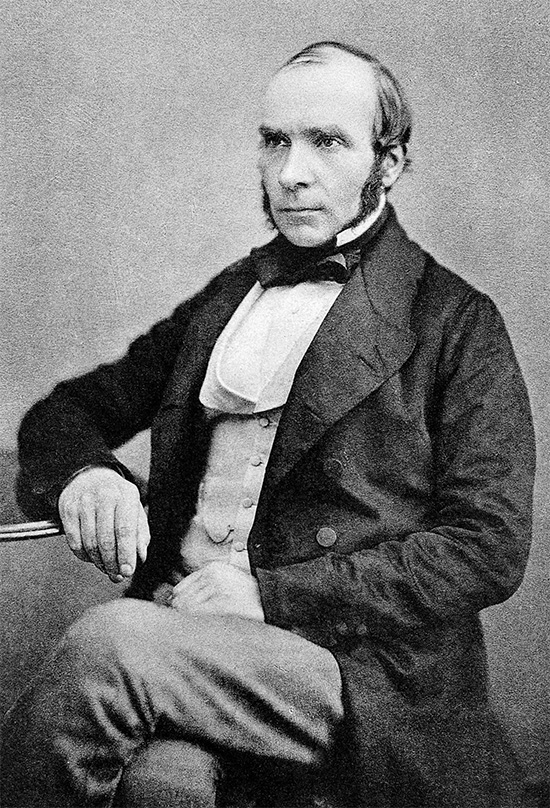

John Snow (1847) by Thomas Jones Barker

Let us begin with a brief recap of his history. Yorkshire born and bred, the eldest of nine children, Snow's early life was distinguished by the singular success of his father, William Snow, who achieved a remarkable upward social mobility. At the time of John's birth, the family lived in North Street, within York's city walls and William was a labourer. Over the next decade or so William progressed through a succession of jobs and by 1832 had become a landowning farmer, subsequently moving to

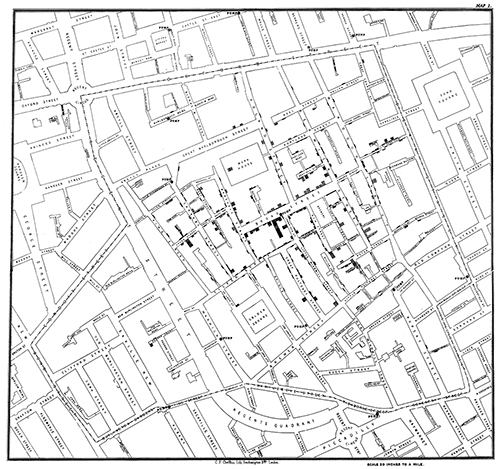

Street map of cholera deaths in 1853 from John Snow's On the Mode of Communication of Cholera

a farm on the outskirts of York. That he gave his children a basic education, which for Snow included Latin and Greek, was no easy achievement as the cost would have placed a strain on a tight family budget; but it provided Snow with an entree to a medical apprenticeship that he served with William Hardcastle in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne. On completion and after a couple of assistant posts to family doctors, Snow set off for London where after 2 years of training he gained qualifications from the Royal College of Surgeons and the Society of Apothecaries. Then Snow bucked the trend. Rather than return to his native Yorkshire he nailed up his colours in Soho and spent the next 10 years researching topics such as respiration and gas chemistry, promoting his research through the medical society network, and scratching a living from a small general practice.

The opportunity to improve his fortunes arose in December, 1846, when news of American experiments with ether for surgical pain relief reached London. Snow grasped the invention with both hands. Within 6 months, he had established the scientific principles of the anaesthetic process, developed a growing practice, and written a short but well received book. Chloroform, discovered by Sir James Young Simpson in November, 1847, swiftly replaced ether in most parts of the world and Snow's research and practice continued to burgeon. From the late 1840s, his contribution was embedded in the history of the specialty and he still features large. But anaesthesia was not his only interest.

In 1849, after gathering evidence from the 1848 epidemic of cholera, Snow published a short pamphlet suggesting that water was the main vehicle of dissemination. His theory competed with many other explanations and was brusquely dismissed by most commentators. 5 years later, an outbreak in Broad Street, Soho, close to his home, provided the opportunity to gather fresh evidence. This research, together with the results of his investigations of the comparative incidence of cholera in homes supplied by two of London's water companies, formed his second publication. On the Mode of Communication of Cholera (1855) was self-funded; only 56 copies were sold. That year Snow gave evidence to the Select Committee set up to gather evidence for the Nuisances Removal and Diseases Prevention Bill. "I believe that epidemic diseases are propagated by special animal poisons coming from diseased persons, and causing the same diseases to others... but that...ordinary decomposing animal matter, will not produce disease in the human subject", he replied to one of the questions. The Lancet was virulent in its condemnation:

"The fact is that the well whence Dr Snow draws all sanitary truth is the main sewer. His specus, or den, is a drain. In riding his hobby very hard, he has fallen down through a gully-hole and has never since been ableto get out again."

Snow's critics challenged the exclusivity of his theory and his refusal to engage with other explanations of cholera's spread. But after his death, from the 1860s onwards, Snow's theory gained momentum. In 1883, Robert Koch identified the cholera vibrio, and in 1890 John Simon, the first UK Medical Officer of Health, who had previously discounted Snow's theory, spoke of it as "the most important truth yet acquired" for the prevention of epidemic disease. Nevertheless, Snow remained largely unknown in epidemiology and public health until the 1930s when interest in his work was reignited by the republication of On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, by Wade Hampton Frost, the first professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health in Baltimore, USA. Frost built a trajectory from the work of Girolamo Fracastoro, a 16th-century Italian physician and poet whose theory of contagion rested on ideas of "seeds of disease", to Snow's "nearly perfect model" study of cholera and thence to contemporary epidemiology. Snow's argument, claimed Frost, "has the permanence of a masterpiece in the ordering and analysis of a kind of evidence which enters at some stage and in some degree into every problem in epidemiology". From this point Snow became the exemplar of epidemiological thought and practice.

So what can we learn from these two tales? The first point to acknowledge is that Snow's history does have a natural dramatic undertow. He was a poor working-class boy who, by dint of hard work, ambition, and tenacity became a respected London anaesthetist and his best-known patient was, of course, Queen Victoria. He provides a fine example of Victorian achievement in the best Smilesian tradition. If his story inspires others to apply equal dedication to medicine and science then that is all to the good. His place in the history of anaesthesia is tethered to the roots of what he did, although at the time, his use of technology to administer anaesthetics was not shared by most doctors - they used a handkerchief or cloth with equally good results. More worrying is the depiction of Snow's cholera theory as a eureka moment of discovery when science shed its blinding light on past ignorance. We are in danger of misrepresenting and thus confusing our understandings of the past if we fail to take into account the nuances of 19th-century beliefs. Then, ideas on the spread of disease were not crudely polarised between contagionists like Snow, and others who believed disease spread through the miasma (bad air) emanating from organic waste on the streets. Rather, there was a complex discourse and, understandably, most doctors preferred to cover all the options. late 19th-century reductions in mortality from cholera owed more to general improvements in water supplies than to Snow's theory.

The emergence of Snow as the hero of epidemiology in the 1930s says more about interwar professional concerns than about early Victorian London. During the early 20th century, epidemiology was often seen as the poor relation of bacteriology. Frost sought to integrate epidemiology with the structures of public health, thereby establishing its importance. His enterprise required defining and constructing a clear identity for epidemiology. It is no surprise that Frost turned to history and chose Snow's work as a compelling example of the contribution epidemiology could make to society. The 150th anniversary of Snow's death will prompt celebrations of his work worldwide. But athough it is right to pay tribute to his contributions to medicine, we should also acknowledge the extent to which his work has been used to make simple tales from complex histories. Eureka moments can inspire, but they rarely sustain doctors who have to make decisions in conditions of uncertainty, without the bright light of retrospect.

Stephanie J Snow

Centre for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine, University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PL, UK

[Frerichs comment] And so regarding being a "hero," what are we to make of Dr. William Farr's comment? He was the long term Compiler of Abstracts at the General Register Office in England and firm supporter of the miasma theory. Also, he is viewed by many as the father of vital and health statistics. In his report of 1866 and on the cholera epidemic, Farr changed his mind and publically acknowledged that Snow's theory strongly espoused in 1854-55 "turned the current in the direction of water," as the mode of cholera transmission. Or as mentioned in Stephanie Snow's article, highly respected Dr. John Simon, the first UK Medical Officer of Health who like Farr had previously discounted Snow's cholera theory. But then in 1890, Simon spoke of the issue [Snow's explanation of how cholera is spread] as "the most important truth yet acquired" for the prevention of epidemic disease. And then there was Reverend Henry Whitehead, also a believer in the miasma theory when first participating in the investigation of the Broad Street Pump Outbreak, but then later had a change of mind. At his farewell dinner on January 16, 1874 at the Rainbow Tavern, he spoke of John Snow: "as great a benefactor in my opinion to the human race as has appeared in the present century." Many other admiring voices for Snow can be found in 19th century British public health literature, long before America's Wade Hampton Frost's involvement, praising Snow for using scientific investigation to overcome community fears, thereby improving the public's health. Hero? Likely so.

UPDATED OBITUARY OF JOHN SNOW IN THE LANCET (2013)

Source: The Lancet, Volume 381, Issue 9874, pp 1269-1270, April 13, 2013.

Sandra Hempel, Journalist and author of The Medical Detective: John Snow, Cholera and the Mystery of the Broad Street Pump, (2006) was commissioned by The Lancet to write an updated obituary of Dr. John Snow that reflected the views in 2013 of the journal. While 155 years had passed since the death of Dr. Snow, the historical perspective in 2013 of his many achievements during his 45 year life span has stimulated a new reality of his ground-breaking work in both anesthesiology and epidemiology.

Below is John Snow's long over-due obituary in The Lancet. For more details on the insightful medical officer John French at the Poland Street Workhouse see last paragraph above in MORE ABOUT LETTER-WRITERS.

John Snow

Physician, epidemiologist, and anaesthetist. Born in York, UK, on March 15, 1813, he died in London on June 16, 1858, aged 45 years.

The Lancet wishes to correct, after an unduly prolonged period of reflection, an impression that it may have given in its obituary of Dr John Snow on June 26, 1858. The obituary briefly stated: “Dr John Snow: This well-known physician died at noon, on the 16th instant, at his house in Sackville Street, from an attack of apoplexy. His researches on chloroform and other anaesthetics were appreciated by the profession.”

The journal accepts that some readers may wrongly have inferred that The Lancet failed to recognise Dr Snow’s remarkable achievements in the field of epidemiology and, in particular, his visionary work in deducing the mode of transmission of epidemic cholera. The Editor would also like to add that comments such as “In riding his hobby very hard, he has fallen down through a gully-hole and has never since been able to get out again” and “Has he any facts to show in proof? No!”, published in an Editorial on Dr Snow’s theories in 1855, were perhaps somewhat overly negative in tone.

Even allowing for Lancet founding Editor Thomas Wakley’s surprising contempt for Snow, the obituary was extraordinary in its brevity and its failure even to mention cholera. The excoriating Editorial 3 years earlier had been provoked by Snow’s support for what were known as the “nuisance traders”. Snow told Members of Parliament that the foul smells from processes such as tanning and soap boiling were not capable of producing acute fever or epidemic disease in an individual. Wakley, incensed at what he saw as an attempt to block important public health reforms, accused Snow of unscientific thinking.

The following year, The Lancet published Snow’s paper “On the Supposed Influence of Offensive Trades on Mortality”, which used the Registrar-General’s Weekly Returns of Deaths in London to argue that workers in the nuisance trades suffered no more ill health than those in other occupations. Wakley followed this, however, with an Editorial that stated there was no doubt that the noxious gases and vapours of the capital’s air exerted “a most efficient and malignant influence in the causation and aggravation of disease”.

Wakley may have been the most outspoken of Snow’s critics but his views were shared by most medical men at the time: miasma, or the stench from decaying vegetable and animal matter, was widely held responsible for epidemic disease. Snow’s On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, first published in 1849, set out the then radical idea that cholera was a disorder of the digestive system not the blood; and that it was contagious and spread through the oral-faecal route, largely through contaminated drinking water.