Stream 5- Additional Items

h: William Farr - Campaigning Statistician

Source: Halliday, Steven. William Farr: Campaigning Statistician Journal of Medical Biography 8, 220-227, 2000. (reproduced with permission of Royal Society of Medicine with consent of author).

William Farr: Campaigning Statistician by Stephen Halliday

AUTHOR: Stephen Halliday is a lecturer at Buckinghamshire Business School who has made a special study of the history of engineering. In addition to the article on William Farr, he is author of The Great Stink of London: Sir Joseph Bazalgette and the Cleansing of the Victorian Capital, Sutton Publishing, Phoenix Mill, Thrupp, Stroud, Gloucestershire GL5 2BU, 1999. His interest in Sir Joseph Bazalgette was aroused by a casual reference in a television program to the way in which cholera was eliminated from Victorian London by the massive engineering works which Bazalgette completed in the face of appalling difficulties. Dr Halliday spent four years researching the achievements of this great engineer, a quest which took him to Budapest and to remote regions of France as well as to subterranean London. Dr Halliday has also written for the Guardian, Observer and Financial Times. He can be contacted at: Dr Stephen Halliday, Buckinghamshire Business School, Newland Park, Chalfont St Giles, Buckinghamshire HP8 4AD, United Kingdom.

PART 1

In 1838, the Office of the Registrar-General was established with the task of registering births, marriages and deaths. The first Registrar-General was a soon-forgotten popular novelist called Thomas Lister, but the dominant figure in the new service was William Farr (1807-1883) (Figure 1, circa 1870), who was appointed as the first "compiler of abstracts" (chief statistician) to the new office. Farr remained in the post until his retirement in 1880, and used his position to become one of the leading figures in the sanitary movement, which campaigned for better sanitary conditions, especially in urban areas. For this work he earned an international reputation.

William Farr's early life

Farr was born in the village of Kenley, Shropshire, on 30 November 1807, the son of parents of modest means. At the age of two he went to live with Joseph Pryce, a local squire noted for his charitable works. Pryce effectively adopted Farr and paid for his education. From 1826 to 1828 Farr travelled each day to Shrewsbury to work as a dresser in the infirmary and to study medicine with a doctor at the infirmary called Webster. On his death in 1828 Pryce left Farr a legacy of 500 pounds which enabled him to pursue his studies in Paris and Switzerland [1].

"Compiler of abstracts"

According to a fellow student called Bain, it was during this period that Farr, who had no mathematical training, first gave evidence of his lifelong interest in medical statistics. During a visit to Martigny, Switzerland, Farr discovered that the community had a large population of individuals suffering from an unusual deformity, and he persuaded the landlord of his inn to assemble a number of them for inspection. When Bain, his travelling companion, returned to the inn: Mr Farr was standing with a table and numerous large sheets of paper before him on which he was marking the shapes of the different heads of which he had previously taken the contours, vertically and horizontally, by means of a leaden tape. That day we dined late.[2]

In 1831 Farr worked for six months as an unqualified surgical locum at Shrewsbury and then studied at University College London, where he became a licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries, the only medical qualification he ever gained by study [3]. In 1833 he married a farmer's daughter who died of consumption in 1837. In 1842 he remarried and had eight children, of whom one son and four daughters survived infancy; his second wife died in 1876. In 1833 he set up as a practicing apothecary in Bloomsbury, London, though from 1835 his earnings from this source were supplemented by writings in early issues of the Lancet, commissioned by the journal's founding editor, Thomas Wakley [4]. Farr's first article, in 1835, was on hygiene, and this was followed by further contributions on quack medicine (1836), life assurance, and cholera (1838) [5].

Farr enjoyed good fortune in his benefactors, since in 1837 he was the recipient of a further 500 pound legacy from Dr Webster, his former Shrewsbury mentor, who also bequeathed to him his large library. In the same year Farr contributed an article on "Vital statistics" for a volume entitledMcCulloch's Account of the British Empire, and at about the same time he became acquainted with Sir James Clark (1788-1870), a fellow of the Royal Society, who became Queen Victoria's physician. It may have been through Clark's influence that Farr obtained the post of compiler of abstracts at an annual salary of 350 pounds, though the social reformer Edwin Chadwick also claimed to have recommended him [6].

Farr quickly recognized that "Diseases are more easily prevented than cured and the first step to their prevention is the discovery of their exciting causes" [7], and he set about establishing a firm foundation for his statistical work. Farr was not the first person to use statistics to identify causes of mortality. A pioneer in the field was William Heberden (1710-1801). Heberden was appointed lecturer in materia medica at Cambridge in 1734 but from 1748 he worked in London as a physician. He undertook a study of the bills of mortality, tabulating causes of death according to categories which now seem strange, such as "suddenly" and "killed by several accidents" [8].

"An authentic name of the fatal disease"

Farr's approach was more systematic. He approached the Presidents of the Royal Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons and the Master of the Society of Apothecaries and persuaded them to write to their members throughout the kingdom, urging them "to give, in every instance which may fall under our care, an authentic name of the fatal disease" [9], to be recorded in the local register books from which Farr compiled his statistics. At the same time, Farr compiled a "statistical nosology" [10], which listed and defined 27 fatal disease categories to be used by local registrars when recording causes of death. Thus dysentery ("bloody flux") was distinguished from diarrhea ("looseness, purging, bowel complaint"). Farr also gave the "synonymes" (sic) and "provincial terms" by which the diseases might be known locally. Letters were drafted in the name of the Registrar-General setting the qualifications which were necessary for local registrars, and instructions were also issued to ships' captains concerning their responsibilities [11].

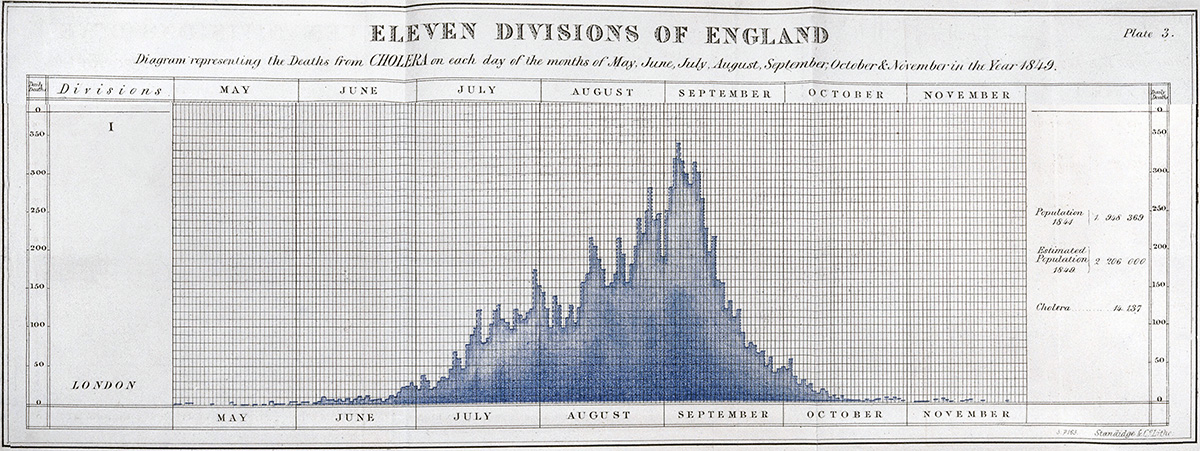

It was Farr's practice, from the first reports, to tabulate causes of death by disease, parish, age, sex, and occupation. A separate section was concerned with the sanitary condition of London, and 13 other principal cities were also regularly the subject of such analysis. Farr regularly included long essays or accounts of related matters. Thus in the report for 1842 he gave an account of the statistical practices of 15 European countries and the USA, and in the 1849 report he included a long essay on life assurance, a theme to which he frequently returned. Farr quickly established a reputation for his skills as an advocate of reform. He was an exceptionally lucid writer and used this gift in letters which were attached to each annual report of the Registrar-General and which drew attention to an issue which concerned him.

Example of Farr Report during 1849 Nationwide Cholera Epidemic (only London is shown)

Example of Farr Report during 1849 Nationwide Cholera Epidemic (only London is shown)

End of Aside)

End of Aside)

"All smell is disease"

However, in the words of one of his admirers, "He was not always well advised in holding to his opinions in the teeth of contradictory evidence" [12]. This paradox is illustrated by his attitude towards the cholera epidemics which killed almost 40,000 Londoners between 1831 and 1866. Farr produced statistical evidence that the cholera was spread by polluted water, yet he long avoided this conclusion, preferring to cling to the orthodox explanation of disease propagation, which held that epidemic disease was caused by foul air (a "miasma"). Advocates of the "miasmatic" theory included Florence Nightingale and Edwin Chadwick, who expressed the view at its most extreme form in evidence to a Parliamentary Committee in 1846, claiming that: All smell is, if it be intense, immediate acute disease; and eventually we may say that, by depressing the system and rendering it susceptible to the action of other causes, all smell is disease.[13]

The miasmatic doctrine proved to be an obstacle to an understanding of waterborne diseases such as cholera and typhoid, and Farr himself clung to the belief long after his own statistics threw doubt upon it.

A "disease mist.. . an angel of death"

Thus, in the fifth annual report, Farr drew attention to the wide variations in mortality between different areas and particularly emphasized the high death rates recorded in London, a feature that he attributed to the "miasma" in which most of the population lived and which he described in thefollowing terms: Every population throws off insensibly an atmosphere of organic matter.., this atmosphere hangs over cities like a light cloud, slowing spreading, driven about, falling dispersed by the winds, washed down by showers.., to connect by a subtle, sickly medium, the people agglomerated in narrow streets and courts, down which the wind does not blow, and upon which the sun seldom shines.[14]

In the tenth annual report, published in 1847, he estimated that in the capital "At least thirty-eight people died daily in excess of the rate of mortality which actually prevails in the immediate neighborhood" [15]. He followed this with an even more emphatic "miasmatic" explanation for this phenomenon, and suggested that the legislature had a responsibility to introduce preventive measures: This disease mist, arising from the breath of two millions of people, from open sewers and cesspools, graves and slaughter-houses, is continually kept up and undergoing changes; in one season it was pervaded by Cholera, in another by Influenza; at one time it bears Smallpox, Measles, Scarlatina and Whooping Cough among your children; at another it carries fever on its wings. Like an angel of death it has hovered for centuries over London. [16]

Farr's work was carried out at a time when the sanitary condition of the metropolis was being radically improved by the great engineering works executed by Sir Joseph Bazalgette (1819-1891) (Figure 2, 1865. His intercepting sewers put an end to the cholera epidemics which puzzled Farr and his colleagues on the Committee for Scientific Enquiry into the 1854 outbreak.), whose system of main drainage, constructed between 1859 and 1875, intercepted London's sewage and conducted it to outfalls beyond the metropolitan boundary, where it did not threaten the capital's water supply [17]. Farr himself, by his statistical analyses, provided much of the evidence to show that polluted water rather than foul air was the medium by which epidemics were spread, thus challenging the conventional "miasmatic" explanation of disease propagation. However, such was the strength of the belief in his own mind and others' that he long resisted the conclusions to which his statistics pointed. The paradox of Farr's commitment to a doctrine on which his work cast doubts is illustrated by his work on cholera.

"What is cholera?"

The arrival of cholera in Britain in 1831 was attended by a degree of anxiety unprecedented since the plague in the seventeenth century, and 30 riots caused by concern about the disease were recorded in 1832 [18].

Each subsequent outbreak prompted further theorizing, over 700 works on the subject being published in London alone between 1845 and 1856 [19]. In the absence of the later discovery by Robert Koch that cholera is usually spread in hot weather by water which has been contaminated by infected feces [20], the epidemics which afflicted Britain between 1831 and 1866 [21], and their possible remedies, were the subject of conjecture informed by despair.

In November 1831, early in the first outbreak that struck Britain, the Lancet reported from Vienna that a community of Jews in Wiesniz had escaped its effects by rubbing their bodies with a liniment containing wine, camphor powder, mustard, pepper, garlic, and ground beetles [22]. In 1853, as the third epidemic made its way across Europe towards Britain, the Lancet speculated on the nature of the disease: What is cholera? Is it a fungus, an insect, a miasma, an electrical disturbance, a deficiency of ozone, a morbid off-scouring of the intestinal canal? We know nothing; we are at sea in a whirlpool of conjecture. [23]

In 1853 the Lancet was no better informed than The Times had been four years earlier when, at the height of the second cholera epidemic, the newspaper had published a series of articles in which the possible causes of the disease, and its remedies, were debated [24]. On 13 September the writer listed the current theories, starting with "The Telluric theory [which] supposes the poison of cholera to be an emanation from the earth". He then considered the "Electric theory", which attributed disease to atmospheric electricity, and the "Ozonic theory", which laid the blame on a shortage of ozone. He briefly considered the idea that the epidemic was caused by "Emanations from sewers and graveyards.., for such an hypothesis we can find no solid foundation". Much space was devoted to the "Zymotic theory", which was particularly associated with Justus von Liebig, Professor of Organic Chemistry at the University of Giessen. Liebig believed the putrefaction of bodies which had suffered from the disease could produce ammonia, which could be "the means through which the contagious matter received a gaseous form" [25], thereby creating a "miasma' in the atmosphere that would spread the infection.

These theories resolved themselves into the idea that epidemic disease was caused by an atmosphere poisoned by disease, evidence for which could take the form of a foul smell. The idea had a long history. Hippocrates had noted that certain fevers were associated with warm weather and with wet, poorly drained places where the air was dank and foul. In 1844, in evidence to the Royal Commission for Enquiring into the State of Large Towns and Populous Districts, Dr W H Duncan, later Liverpool's (and England's) first city medical officer, told the Commissioners: By the mere actions of the lungs of the inhabitants of Liverpool, for instance, a stratum of air sufficient to cover the entire surface of the town, to a depth of three feet, is daily rendered unfit for the purposes of respiration.[26]

As late as 1890, the last year of his life, Edwin Chadwick made a speech to the Society of Arts in which, in the words of the Builder: Sir Edwin concluded his somewhat prolix communication by advocating the bringing down of fresh air from a height by means of such structures as the Eiffel Tower, and distributing it warmed and fresh, in our buildings.[27]

PART 2

John Snow's On... Cholera

In the meantime, the most significant contribution to an understanding of the true causes of cholera epidemics was being made by Dr John Snow (1813-1858). In 1849, he published On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, in which he suggested that water polluted by sewage might be the vehicle by which cholera was transmitted (Figure 3).

He argued that the practice of flushing sewers into the river made the 1849 epidemic worse. During the 1854 epidemic Snow observed that a high incidence of cholera was occurring among persons drawing water from a well in Broad Street [28], Soho, near Golden Square, London, close to his medical practice. Further investigation revealed that a sewer passed close to the well. Snow persuaded the parish council to remove the handle which operated the pump [29].

While some medical authorities were prepared to acknowledge that polluted water had some role in the propagation of disease as a predisposing cause, few were prepared to acknowledge it as the specific cause despite the evidence of Snow's observations and the lucidity of his arguments. Snow advocated the use of filters by water companies and advised that water be boiled before use during cholera outbreaks.

Farr and the Broad Street pump

In 1855 Farr served on the Committee for Scientific Enquiry into the cholera epidemic of the previous year. Farr used the data gathered by his office to draw a diagram which illustrated the relationship between the incidence of mortality from cholera and the elevation of the affected districts, using the figures compiled for the whole epidemic. Farr's diagram [30] revealed the incidence of mortality from cholera (Table 1).

This clearly demonstrated that the further removed a district was from the lowest point (the polluted Thames), the lower the mortality [31]. The most striking exception to this inverse relationship between mortality and elevation was shown by Farr's diagram to lie in the vicinity of Golden Square, close to the site of the pump which, according to John Snow, was supplying the locality with infected water. Nothing could better illustrate the strength of the miasmic doctrine than the Committee's explanation: We cannot help thinking that the outbreak arose from the multitude of untrapped and imperfectly trapped gullies and ventilating shafts constantly emitting an intense amount of noxious, health-destroying, life-destroying exhalations.[32]

They further observed that the enclosed character of the area meant that there was no wind to disperse the noxious vapors except at corners of streets, and they took comfort from the fact that the incidence of deaths from cholera had been rather lower in corner houses than in others [33].

Commenting upon Snow's conclusion that this phenomenon was due to the use of infected water from the Broad Street pump, Farr and the rest of the Committee concluded: In explanation of the remarkable intensity of this outbreak within very definite limits, it has been suggested by Dr Snow that the real cause of whatever was peculiar in the case lay in the general use of one particular well, situate [sic] at Broad Street in the middle of the district and having (it was imagined) its waters contaminated by the rice-water evacuations of cholera patients. After careful enquiry we see no reason to adopt this belief.[34]

Despite the evident connection between the water of the Thames, the water of the pump, and the incidence of cholera, the "miasmic" orthodoxy was at this stage so strong that Farr and his colleagues sought an atmospheric explanation, concluding that: If the Broad Street pump did actually become a source of disease to persons dwelling at a distance, we believe that this may have depended on other organic impurities than those exclusively referred to, and may have arisen, not in its containing choleraic excrements, but simply in the fact of its impure waters having participated in the atmospheric infection of the district.., on the whole evidence, it seems impossible to doubt that the influences, which determine in mass the geographical distribution of cholera in London, belong less to the water than to the air.[35]

This report was written by Farr and his colleagues in July 1855, but within 12 months Farr was beginning to doubt this conclusion. In an appendix (written in late 1855 or 1856) to the 1854 annual report of the Registrar-General, Farr made a careful analysis of the incidence of cholera among customers of 10 London water companies (Figure 4, An extract from Farr's report on mortality from cholera, published in the annual report of the Registrar-General for 1854, which showed the relationship between water sources and cholera.) and noted that the Lambeth company, which had moved its intake to Teddington, beyond the tidal river, had seen a rapid fall in mortality among its customers compared with the 1849 epidemic. Farr made reference to the work of John Snow and wrote that "the cholera matter, where it is most fatal, is largely diffused through water, as well as through other channels"[36]. Farr is hedging his bets, but the emphasis here, for the first time, is on water as the medium of infection.

The East London epidemic

It was the failure of the East London water company to protect its water supply, combined with the fact that its directors attempted to conceal its failure, that finally convinced Farr the campaigner of the critical role of polluted water in the propagation of cholera (Figure 5, A contemporary view of the perils of drinking-pump water, as depicted in the magazine Fun, in 1866, shows that not everyone regarded air as the cause of epidemics.)

On 27 June 1866, a laborer called Hedges and his wife both died of cholera, aged 46. The Hedges' water closet discharged into the River Lea at Bow Bridge, near the East London water company's reservoir at Old Ford. This should not have mattered, since the company had installed filter beds for its new covered reservoirs and supposedly isolated these reservoirs from its older uncovered reservoirs, which had pervious bottoms. Nevertheless, Farr observed the degree to which the outbreak was concentrated in the area served by the East London company, commenting that "The mortality is terrible just in the area of East London supply" [37]. The engineer of the company, Charles Greaves, wrote to The Times on 2 August 1866 to refute the suggestion that contaminated water had been allowed to enter the drinking water supply: "not a drop of unfiltered water has for several years past been supplied by the company for any purpose" [38].

Location of East London Water Company

Location of East London Water Company

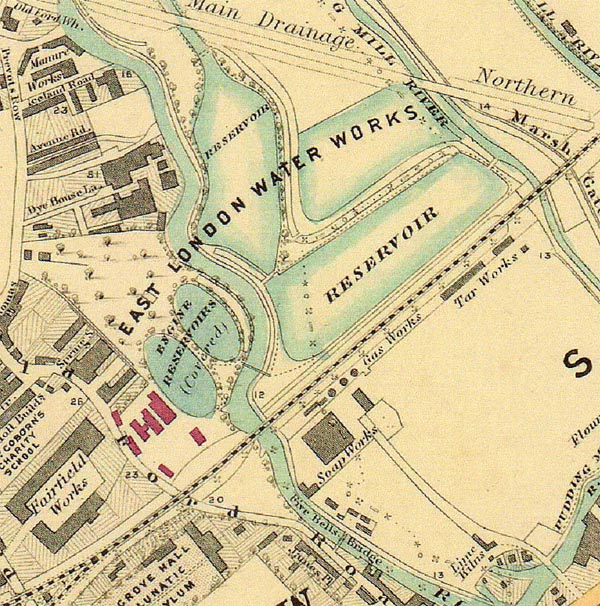

The East London Waterworks Company was established in 1807 on 30 acres of land at Old Ford Bow, east of London, with water coming from the River Lea. Here they built a pumping station and drew water from the River Lea which was about 4 feet higher than the River Thames, and up to 5 feet higher with the rise of the tide. In 1829 the intake was moved higher up the River Lea, further from the effects of tide and population. A year later they built a canal from the Lea Bridge area of the Lea River, across Hackney Marsh to Old Ford. A large reservoir was constructed to receive the water, as seen below in Stanford's map of 1862.

The headquarters (in red) of the East London Water Works in 1862 was on Old Ford Road, just west of the River Lea. Two small covered reservoirs were on the west side of the River Lea and four large uncovered reservoirs were on the east side of the River Lea. To the south is Bow Road which becomes High Street (Bow) near the river.

In an enlarged view, the two covered reservoirs are shown in 1862 next to the headquarter buildings of the East London Water Works, right by Old Ford Road (see in red). The water was drawn from the river and held in reservoirs to remove sedimentation, then distributed to customers.

Source: Stanford's Library Map of London and its Suburbs. Published by Edward Stanford, 6, Charing Cross, London, February 15, 1862.

End of Aside)

End of Aside)

On 3 August Farr visited Old Ford and requested an analysis of the company's water. He observed that, though Greaves's letter to The Times had claimed that all its water was filtered, two customers of the East London company claimed that they had found eels in their water pipes [39]. Farr also wrote to Joseph Bazalgette the same week about the possibility of waste entering the water supply. Since 1859 Bazalgette had been constructing the main drainage system which intercepted the sewage before it reached the Thames and conducted it to treatment works and outfalls at Barking and Plumstead, well beyond the metropolitan boundary. Most of the system was now in operation but Bazalgette replied to Farr: "It is unfortunately just the locality where our main drainage works are not complete. The low-level sewer is constructed through the locality, but the pumping station at Abbey Mills will not be completed until next summer.... I shall recommend the Board to erect a temporary pumping station at Abbey Mill to lift the sewage of this district into the Northern outfall sewer. This can be accomplished in about three weeks."[40]

In the same week that he wrote this letter, Bazalgette began to install a temporary pumping station to lift the sewage into the outfall and thereby protect the area from its own waste.

In September, the number of deaths from cholera rapidly fell, but 29 customers of the East London Company signed a "memorial" to the Board of Trade in which they alleged that their water supplies were being contaminated by water from the River Lea [41]. A Captain Tyler, who was appointed to report upon the matter, questioned the company's employees and discovered that on three occasions, in March, June and July 1866, a 24-year-old carpenter had admitted water to the company's closed reservoir (from which drinking water was drawn) from an old, uncovered reservoir which was vulnerable to contamination, in breach of the 1851 and 1852 Metropolis Water Acts.

Tyler wrote: "a case of grave suspicion exists against the water supplied by the East London Company from Old Ford". He estimated that 4,363 deaths had occurred between 1 July and 1 September, of which 3,797 had occurred in areas supplied only by the East London Company and a further 264 in an area which it shared with the New River Company. Thus 93% of deaths had occurred in areas supplied wholly or in part by the East London Company [42].

Farr, whose own enquiries had been instrumental in exposing the company's attempts to conceal the truth, concluded that this was the means by which the infection had spread to other houses in the area and his anger, partly at the deaths which resulted and partly at the company's attempted deception, is reflected in the "Report on the cholera epidemic in England", which he appended as a supplement to the Registrar-General's 1866 annual report. Farr tabulated the death rates per thousand population in the three cholera outbreaks of 1849, 1854, and 1866, and drew attention to the fact that, in most of London's parishes, the 1866 epidemic had been by far the least deadly, the marked exceptions to this trend falling in seven East End parishes, all of which were supplied by the East London Company, while three also received supplies from the New River Company [43].

PART 3

"The air has had the worst of it"

In the same report, he wrote of the debate on the roles of air and water in disease propagation and gave much more favorable consideration to Snow's theory than he had in the past, using passages in which he made good use of his gift for lucid writing and in which his anger is barely concealed: As the air of London is not supplied like water to its inhabitants by companies the air has had the worst of it.... For air no scientific witnesses have been retained, no learned counsel has pleaded; so the atmosphere has been freely charged with the propagation and the illicit diffusion of plagues of all kinds; while Father Thames, deservedly reverenced through the ages, and the water gods of London, have been loudly proclaimed immaculate and innocent.... In vain did the sewers of London and of twenty towns pour their dark streams into the Thames and the Lea; their waters were assoiled [sic] from every stain by chemists who had carefully analyzed specimens collected by the water companies.... Dr Snow's theory turned the current in the direction of water, and tended to divert attention from the atmospheric doctrine, which in London has received little encouragement from experience. The theory of the East wind with cholera on its wings, assailing the East End of London, is not at all borne out by the experience of previous epidemics.... An indifferent person would have breathed the air without any apprehension; but only a very robust scientific witness would have dared to drink a glass of the waters of the Lea at Old Ford after filtration. [44]

This acceptance that cholera was primarily waterborne was a significant shift from Farr's position in the earlier outbreak of 1854, when, along with his fellow members of the Committee for Scientific Enquiry, he had explicitly rejected Snow's hypothesis. By 1866, faced by the evidence of the East London Company's practices, and no doubt offended by their attempt to conceal them, Farr had clearly accepted Snow's explanation. It was at this time that Farr, a late convert to the belief that cholera could be waterborne, paid his tribute to Bazalgette's system (Figure 6, Bazalgette's pumping station at Abbey Mills, opened in 1868, finally protected the East End of London from cholera, although too late for the victims of the 1866 outbreak. This engraving was featured in the Illustrated London News). The accompanying text was: