Stream 2- Broad Street Pump Outbreak

d: Investigation of Broad Street Pump Outbreak

"There were a few cases of cholera in the neighborhood of Broad Street, Golden Square, in the latter part of August; and the so-called outbreak, which commenced in the night between the 31st August and the 1st September, was, as in all similar instances, only a violent increase of the malady. As soon as I became acquainted with the situation and extent of this irruption of cholera, I suspected some contamination of the water of the much-frequented street-pump in Broad Street, near the end of Cambridge Street; but on examining the water, on the evening of the 3rd September, I found so little impurity in it of an organic nature, that I hesitated to come to a conclusion. Further inquiry, however, showed me that there was no other circumstance or agent common to the circumscribed locality in which this sudden increase of cholera occurred, and not extending beyond it, except the water of the above mentioned pump. I found, moreover, that the water varied, during the next two days, in the amount of organic impurity, visible to the naked eye, on close inspection, in the form of small white, flocculent particles; and I concluded that, at the commencement of the outbreak, it might possibly have been still more impure. "

- John Snow in On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, 2nd Edition, London: John Churchill, New Burlington Street, England, 1855, pp. 1-139.

In the Broad Street area between Golden Square and Soho Square there were quite a few water pumps, like that shown below, there to serve the neighboring homes and businesses, those who were just thirsty for a drink, or people needing a pail of water or two for their homes. No money was required -- just a push and pull of the handle. Some preferred the pump on Broad Street, apparently liking the water's taste and hint of effervescence.

Source: Crane W. Fetching water: A scene during the late frost, The London Museum, 1856.

At the end of September [1854] the cholera outbreak described above was all but over, with the death toll standing at 616 people of the Soho neighborhood. But Snow's theories about the involvement of the Broad Street Pump were yet to be proven.

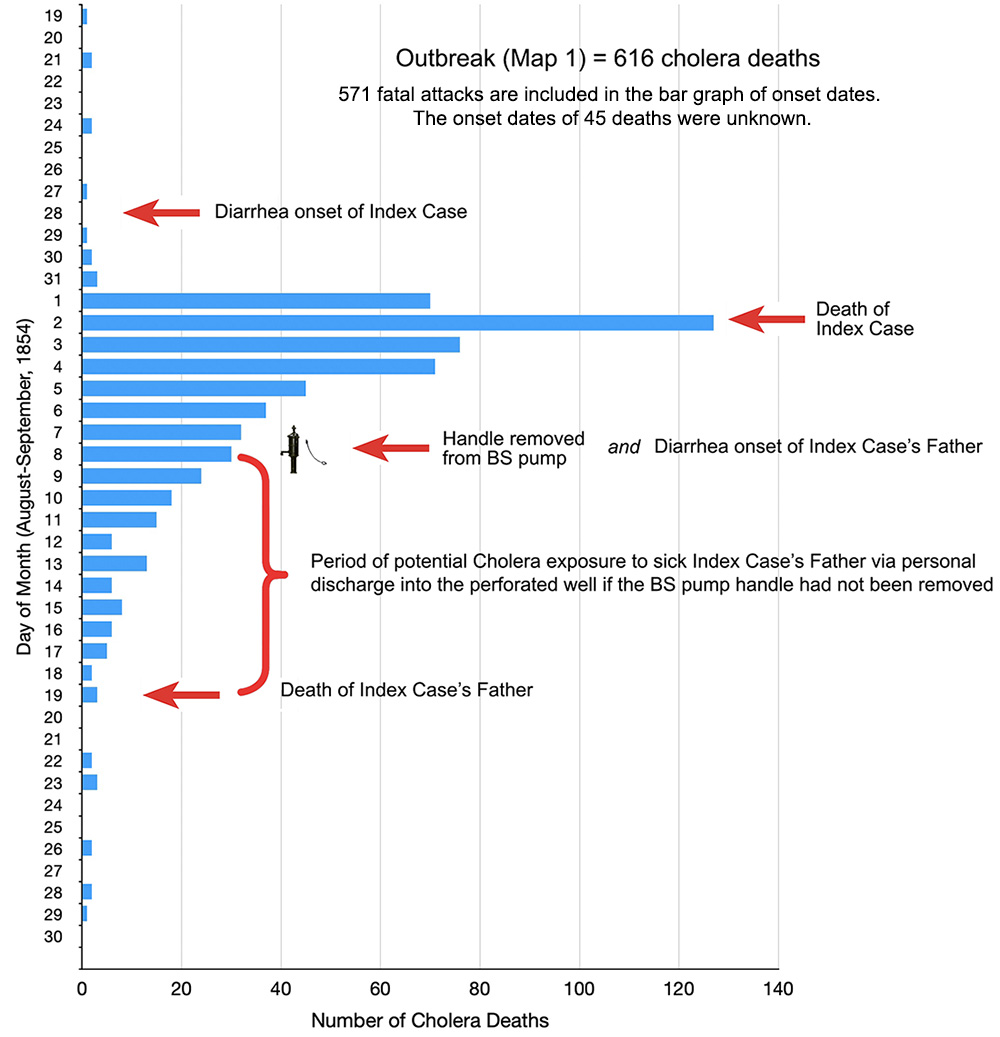

BAR GRAPH OF ONSET TIMES OF FATAL CHOLERA ATTACKS

Snow's Initial Investigation

Having a sense based on past experience that cholera was cause by an infectious microbe that had an incubation period of several days, Snow needed to first decide when the outbreak started, and then investigate the primary deaths (i.e., those due to the initial source) before the full force of the outbreak took off with secondary and tertiary deaths (i.e., those due to prior cases), unrelated to the initial source. Using a wild fire as an analogy, his intent was to discover what started the fire, not which tree or bush was responsible for continuing the fire. Since he lived near by, he became involved from the very beginning.

On the evening of September 3, 1854, Snow started by viewing the water of the Broadstreet pump, noting that "I found so little impurity in it of an organic nature, that I hesitated to come to a conclusion." He looked around and conferred with others, concluding that it "showed me that there was no other circumstance or thing common to the circumscribed locality in which this sudden increase of cholera occurred, and not extending beyond this locality, except the water of the above pump." Determining if the water quality was changing over time, he wrote: "I found, moreover, that the water varied, during the next two days, in the amount of organic impurity it contained; and I concluded that, at the commencement of the outbreak, it might have been still more impure."

His next step was to immediately try to tally the deaths as they occurred over time. To this end, Snow wrote: "I requested permission, therefore, to take a list at the General Register Office of the deaths from cholera registered during the week ending September 2, 1854 in the sub-districts of Golden-square, Berwick-street, and St. Ann's, Soho. Eighty-nine deaths from cholera were registered during the week, in the three sub-districts. Of these, only six occurred in the four first days of the week, four occurred on Thursday, the 31st of August, and the remaining seventy-nine on Friday and Saturday. I considered, therefore, that the outbreak commenced on the Thursday; and I made an inquiry, in detail, respecting the eighty-three deaths registered as having taken place during the last three days of the week." (i.e., August 31st, September 1st and 2nd). The deaths were provided to Snow in a list, along with location, occupation, age and gender.

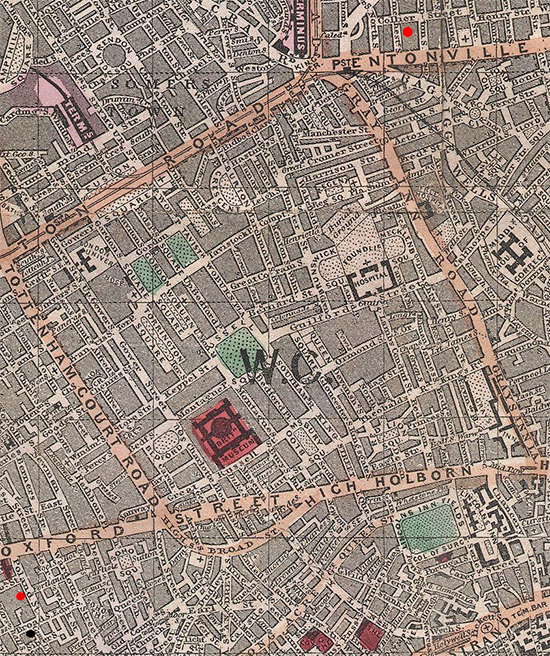

The location of the three sub-districts that Snow selected for his list of early cholera deaths are shown in the map below, along with red dots for reference in Soho Square and Golden Square. The Golden-square Sub-district is tinted gold, the Berwick-street Sub-district is tinted blue, and the St. Ann's Soho sub-district is tinted green .

Source: Arrowsmith, J. and Fitzroy, R. "The Registration Districts of the Metropolis 1843," 10 Soho Square, London, 1843.

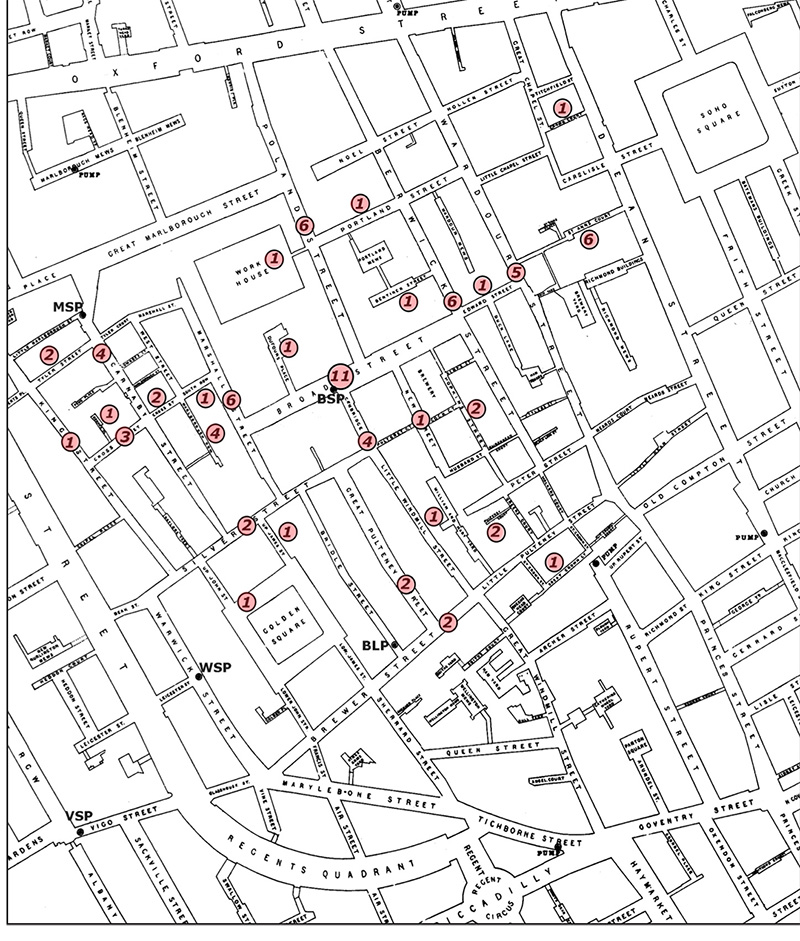

The following map, produced in 2020 by Peter Vinten-Johansen from the General Register Office list, shows the number of deaths in the 83-death series by location in red circles using Map 1 of Snow's Broad Street Pump outbreak. The figure also shows location of the other street water pumps in the area, identified as:

BLP Bridle Lane (street) pump

BSP Broad Street pump

MSP (little) Marlborough Street pump

VSP Vigo Street pump

WSP Warwick Street pump

Modified Source: Vinten-Johansen, P. Investigating Cholera in Broad Street - A History in Documents,

The Broadview Sources Series, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, 2020.

The Broadview Sources Series, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada, 2020.

Snow then took his list to the Broad Street outbreak area and described: "On proceeding to the spot, I found that nearly all the deaths had taken place within a short distance of the pump. There were only ten deaths in houses situated decidedly nearer to another street pump. In five of these cases the families of the deceased persons informed me that they always sent to the pump in Broad-street, as they preferred the water to that of the pumps which were nearer. In three other cases the deceased were children who went to school near the pump in Broad-street. Two of them were known to drink the water, and the parents of the third think it probable that it did so. The other two deaths, beyond the district which this pump supplies, represent only the amount of mortality from cholera that was occurring before the eruption took place. The result of this inquiry, then, is, that there has been no particular outbreak or prevalence of cholera in this part of London except among the persons who were in the habit of drinking the water of the above-mentioned pump-well."

In Snow's field investigation of the first three days of deaths (i.e., August 31 - September 2, 1854), he identified the 83 deaths and interviewed their descendant or household respondents, asking if the person had been a user (either constantly or occasionally) or non-user of the Broad Street Pump. The response was unknown for 8, leaving 75 for his initial analysis of the cases. Of these 75 cholera deaths, 68 were users of the Broad Street Pump (91%), 1 was a probable user (1%), and 6 (8%) were non users, suggesting a strong association of primary cases with the Broad Street Pump.

Alas What Snow did not have was the Broad Street Pump usage pattern of the area population from which the cases arose. A century later, epidemiologists would have routinely linked such case series to a control group of living persons without cholera, location and time matched to the cases, then derive an odds ratio telling of the strength of the association. The design for such case-control studies is now routinely taught in Epidemiology programs, but not during John Snow's lifetime.

Snow's Call for Action

Once he observed the apparent strong association with the Broad Street Pump of the primary deaths in the first three day of the outbreak, Snow took action. He wrote: "I had an interview with the Board of Guardians of St. James's parish, on the evening of the 7th of September, 1854 , and represented the above circumstances to them. In consequence of what I said, the handle of the pump was removed on the following day."

"The number of attacks of cholera had been diminished before this measure was adopted,"reflected Snow, "but whether they had diminished in a greater proportion than might be accounted for by the flight of the great bulk of the population I am unable to say. In two or three days after the use of the water was discontinued the number of fresh attacks became very few."

Snow's Six Questions or Elements

In writing of the Broad Street Pump cholera outbreak of 1854, John Snow addressed six questions or elements in his investigation that involve the Broad Street pump. He was attempting to use all available information to support his hypothesis that contaminated well water caused the outbreak. Snow's text below (in italic) on each of the six elements from his 1855 book is followed with a detailed map of the area showing the exact location of the episode or event.

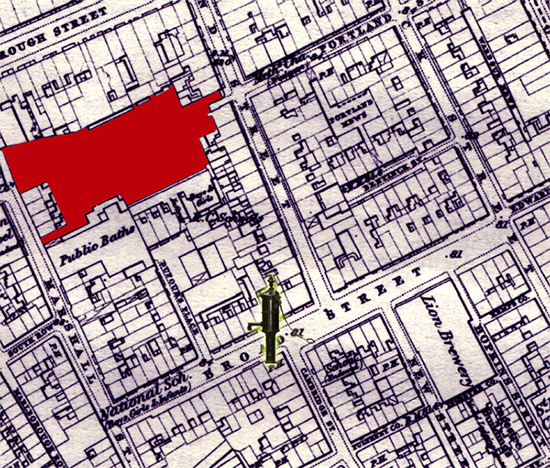

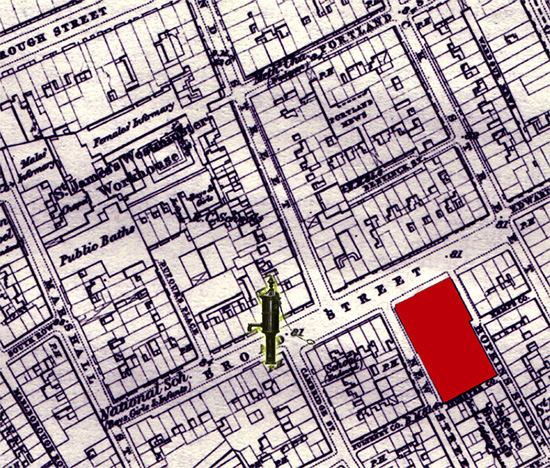

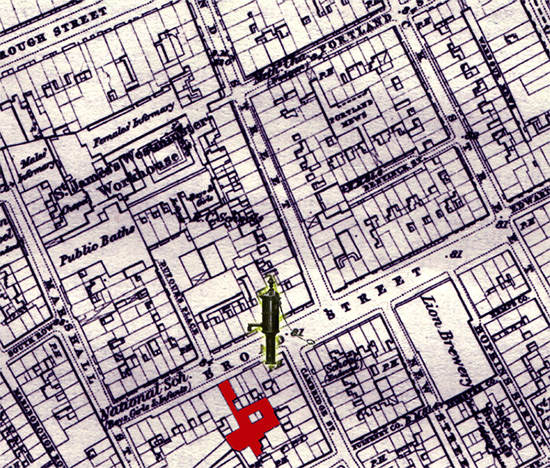

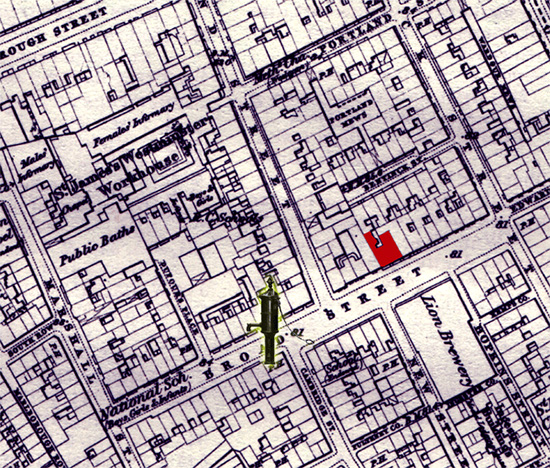

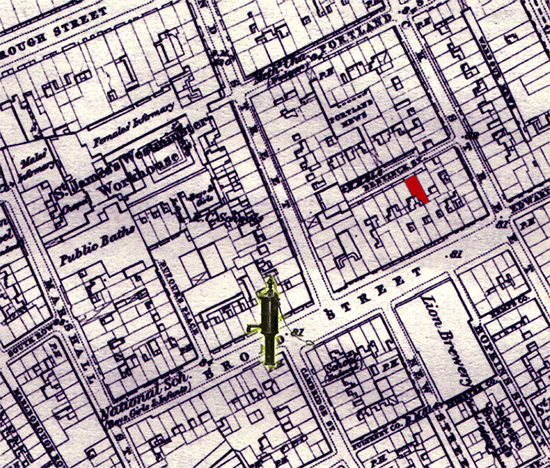

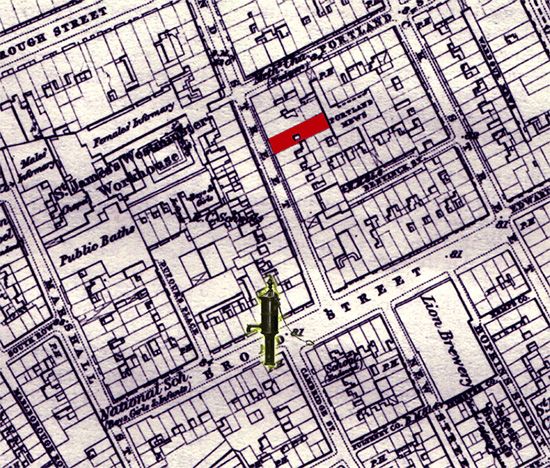

Here are two historical maps of the Broad Street area that show the location ( ) of the Broad Street pump.

) of the Broad Street pump.

The first is Reynold's map of 1859, published five years after the 1854 Broad Street outbreak. Many years later "Broad Street" was renamed "Broadwick Street."

Source: Reynolds's Map of Modern London, Divided into Quarter-mile Sections, James Reynolds, London, England, 1959.

The second map, published by Stanford in 1862, was eight years after the 1854 cholera outbreak outbreak. "

Source: Stanford's Library Map of London and its Suburbs. Published by Edward Stanford, 6, Charing Cross, London, February 15, 1862

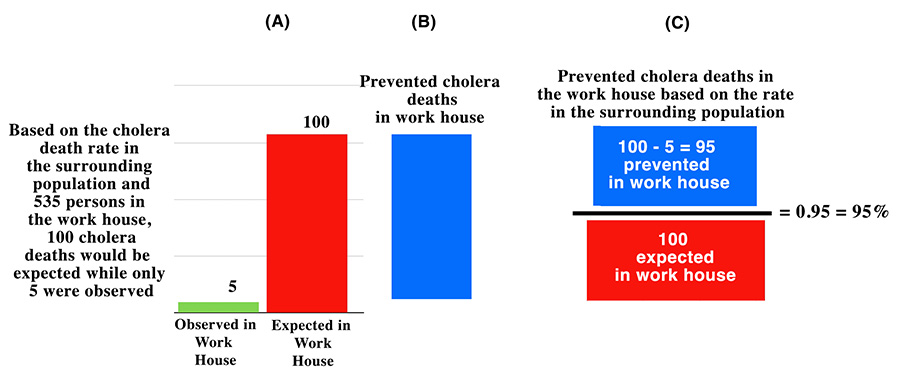

1) Why were most residents of the St. James Workhouse spared from infection?

The Workhouse in Poland Street is more than three-fourths surrounded by houses in which deaths from cholera occurred, yet out of five hundred and thirty-five inmates only five died of cholera, the other deaths which took place being those of persons admitted after they were attacked. The workhouse has a pump-well on the premises, in addition to the supply from the Grand Junction Water Works, and the inmates never sent to Broad Street for water. If the mortality in the workhouse had been equal to that in the streets immediately surrounding it on three sides, upwards of one hundred persons would have died.

- Snow J. On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, 1855, page 42.

The question facing Snow was: "How many cholera deaths in the workhouse were prevented by protective factors associated with the workhouse?" To estimate this in a general manner, epidemiologist turn to the prevented fraction measure. The graphic presentation below illustrates the math that Snow conceptually used when making the above statement.

First, Snow derived the cholera death rate in a defined population (i.e., "immediately surrounding the workhouse on three sides"). He then multiplied this death rate times the 535 persons living in the workshop to derived the estimated number of deaths that would have occurred in the workshouse if the residents had experienced a death rate like that in the surrounding population. This number he found to be 100 expected deaths, way higher than the observed 5 deaths.

As seen in (A), the observed number is 5 (green bar), and the expected number is 100 (red bar), dramatically different, but how different? Subtacting the observed number of deaths from the expected number of deaths (B), Snow found that 95 deaths had been prevented in the workhouse (blue bar). As a general talking point, Snow might have derived the prevented fraction, making it easier for non-epidemiologists to understand the policy implications. To do so, he needed only to divide the 95 prevented deaths in the workhouse by the 100 expected deaths in the workhouse, presenting the results either as a proportion (i.e., 0.95) or a percentage (i.e., 95%) (C). Thus his concluding statement might have been, "we estimate that 95 percent of likely deaths in the workhouse were prevented, probably by the absence of contaminated well water coming from the Broad Street Pump."

The Workhouse in Poland Street (small entrance to the right by Poland Street) is the St. James Workhouse (in red). It sits close to the Broad Street pump but had few cholera cases.

Source: Old Ordnance Survey Maps -- The West End, 1870.

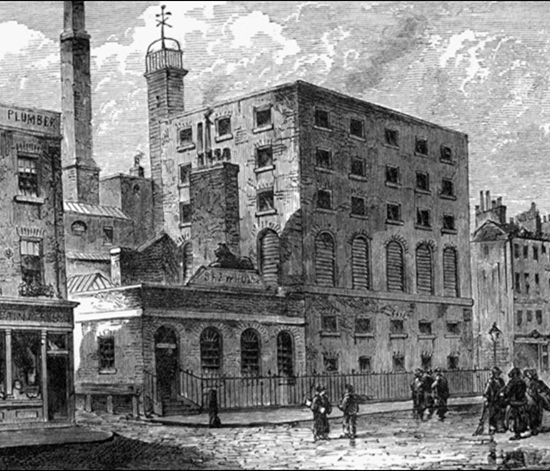

The Workhouse in Poland Street was depicted in late 1809, but had not changed much over the years. A major remodel was planned in 1858, the year of John Snow's death.

Source: Poland Street Workhouse, London, December 1809.

Aside - Grand Junction Water Works

Aside - Grand Junction Water Works

"The Grand Junction Water Works obtain their supply at Brentford [up the River Thames from London by Kew Bridge], within the reach of the tide and near a large population, but they detain the water in large reservoirs, and their officers tell me they filter it; at all events, they supply it in as pure a state as that of the Lambeth Company obtained at Thames Ditton [far upriver beyond the tide], and their districts have suffered very little from cholera..."

- Snow, John. Communication of Cholera, 1855, p. 92-3

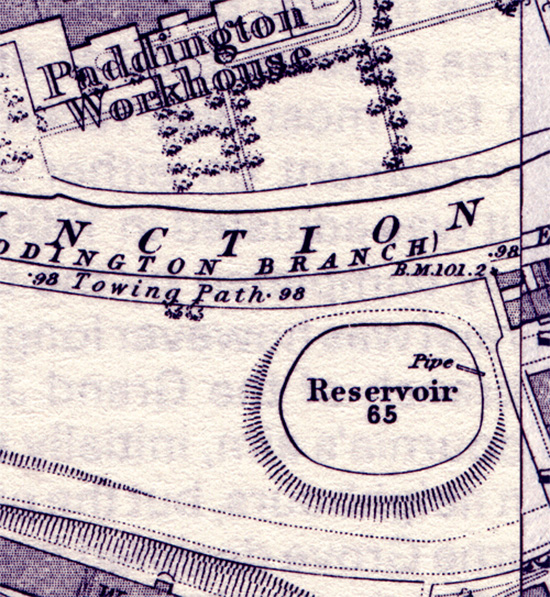

The Grand Junction Company was incorporated in 1811 and had the original intake at Paddington, with water coming from the Grand Junction Canal. Unfortunately the canal supply was meager and dirty, far different from what was promised years earlier to company investors: pure water, a constant supply and cheap rates. The company moved in 1820 to a new site by the Thames River on four acres near Chelsea Hospital. The Paddington site remained with a reservoir but no building. The reservoir can be seen in the 1871 Ordnance map, just south of the Grand Junction Canal below the Paddington Workhouse. The company also owned three reservoirs near Hyde Park which were sold to developers in the early 1850s. It then built a large reservoir at Campden Hill. The three reservoirs North of Hyde Park are shown in Cruchley's map of 1846.

The Grand Junction reservoir remained at the old Paddington site. Just above the reservoir is the Grand Junction Canal.

Source: Old Ordnance Survey Maps -- Notting Hill, 1871.

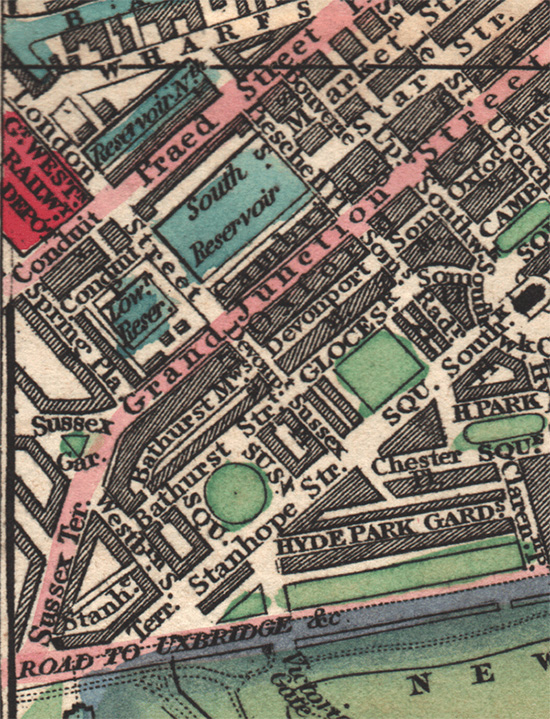

The Grand Junction Company in 1846 owned three reservoirs east of the Great Western Railway Depot (later -- Paddington Station). At the bottom of the map is Hyde Park.

Source: G.F. Cruchley. Cruchley's New Plan of London improved to 1846, Cruchley Map Seller and Publisher, 1846.

In 1852, Parliament decided that no intake from the River Thames would be allowed by any company below Teddington Lock. Responding to this law, the Grand Junction moved in 1853-55 to a new site chosen in Hampton (near the Southwark and Vauxhall and West Middlesex water company sites), where the works remained until the end of the nineteenth century.

End of Aside - Grand Junction Water Works

End of Aside - Grand Junction Water Works

2) Why were there no cases at the Huggins Brewer (previously the Lion Brewery)?

There is a Brewery in Broad Street, near to the pump, and on perceiving that no brewer's men were registered as having died of cholera, I called on Mr. Huggins, the proprietor. He informed me that there were above seventy workmen employed in the brewery, and that none of them had suffered from cholera, -- at least in a severe form, -- only two having been indisposed, and that not seriously, at the time the disease prevailed. The men are allowed a certain quantity of malt liquor, and Mr. Huggins believes they do not drink water at all; and he is quite certain that the workmen never obtained water from the pump in the street. There is a deep well in the brewery, in addition to the New River water [works].

- Snow J. On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, 1855, page 42.

The Brewery on Broad Street used to be the Lion Brewery until one of the owners took the name and relocated to a new location on the banks of the River Thames. Thereafter, the ownership of the Broad Street brewery shifted hands, until 1850 when the Huggins family took control and continued production at the same location (see 1853 site below). The Huggins-owned-brewery (in red in the 1870 map), is only a block away from the Broad Street pump but had no cases.

Source: Altiora Petimus. The great lost brewery of old Soho, April 20, 2020.

Source:Old Ordnance Survey Maps -- The West End, 1870.

New River Water Works - an aside

New River Water Works - an aside

The New River Company (also referred to as the New River Water Works) had been on Snow's mind for some while, starting when he attempted to explain the historical cholera patterns in London following the 1831-2 epidemic. He assumed that contaminated water was to blame and presented evidence to support his hypothesis. Snow noted that the water provided by the New River Company comes from several inputs, including the polluted River Thames.

"The cholera passed very lightly over most of the districts supplied by the New River Company. St Giles' was an exception... The City of London [which received water from the New River Company] also suffered severely in 1832. When the engine at Broken Wharf was employed to draw water from the Thames, this water was supplied more particularly to the City, and not at all to the higher districts supplied by the New River Company."

- Snow, John. Communication of Cholera, 1855, p. 59-60

In the early 1600s, the New River Company constructed a channel to bring water from fresh springs to a pond at New River Headquarters. Improvements occurred in 1768 when steam power was initially used, in 1805 when water was supplied to first-floor premises, and in 1811 when the company replaced wooden pipes with cast-iron pipes. By 1850, the water input to the company was coming from various springs, the River Lea, assorted wells, and from the River Thames at Broken Wharf. After 1852, the company was filtering its water, then also supplying the brewery on Broad Street studied by Snow.

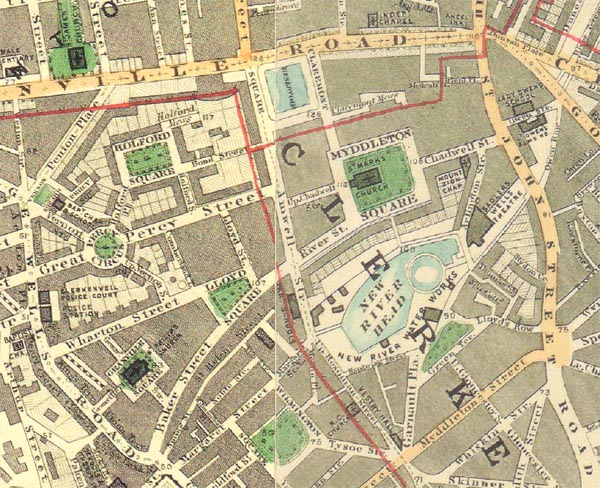

The headquarter buildings of the New River Water Works in the 1862 map is south of Pentonville Road, by Myddleton Square and the Sadler's Wells Theater. The map shows the filter bed surrrounding the headquarter buildings, and the company's reservoir a few blocks north, on Pentonville Road.

Source: Stanford's Library Map of London and its Suburbs. Published by Edward Stanford, 6, Charing Cross, London, February 15, 1862.

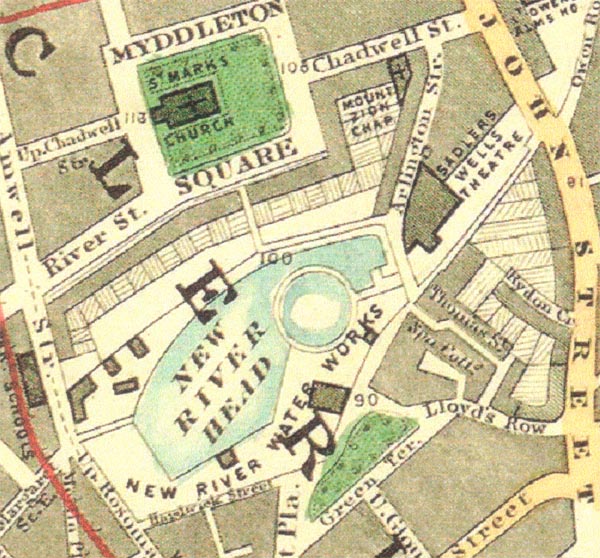

In an enlarged view, the water in the filter bed clearly surrounds the headquarters of the New River Water Works.

End of aside - New River Water Works

End of aside - New River Water Works

3) Many of those who drank pump water brought to a nearby percussion-cap factory became cases.

At the percussion-cap manufactory, 37 Broad Street, where, I understand, about two hundred workpeople were employed, two tubs were kept on the premises always supplied with water from the pump in the street, for those to drink who wished; and eighteen of these work people died of cholera at their own homes, sixteen men and two women.

Mr. Eley, the percussion-cap manufacturer of 37 Broad Street, informed me that he had long noticed that the water became offensive, both to the smell and taste, after it had been kept about two days. This, as I noticed before, is a character of water contaminated with sewage. Another person had noticed for months that a film formed on the surface of the water when it had been kept a few hours.

- Snow J. On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, 1855, page 43.

The Eley percussion-cap manufactory (in red) is very close to the Broad Street pump and had pump water-filled containers on the premises.

Source:Old Ordnance Survey Maps -- The West End, 1870.

4) Some at the neighborhood manufactory of dentists' material became cases and others didn't. Why?

Mr. Marshall, surgeon, of Greek Street, was kind enough to inquire respecting seven workmen who had been employed in the manufactory of dentists' materials, at Nos. 8 and 9 Broad Street, and who died at their own homes. He learned that they were all in the habit of drinking water from the pump, generally drinking about half-a-pint once or twice a day; while two persons who reside constantly on the premises, but do not drink the pump-water, only had diarrhea.

- Snow J. On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, 1855, page 43.

Mr. Marshall of Greek Street, Soho, is renowned anatomist and surgeon John Marshall (1818-1891). He had published a book on cholera in 1831, and likely was a friend of John Snow, helping with his 1854 investigation.

Source: Marshall, John. "Observations on cholera as it appeared at Port Glasgow during the months of July and August, 1831: illustrated by numerous cases", Edinburgh : Waugh and Innes, 1831.

Persons working at the manufactory of dentists' material at Nos. 8 and 9 Broad Street (in red) who drank pump water died at their homes while others who did not drink pump water had only diarrhea.

Source:Old Ordnance Survey Maps -- The West End, 1870.

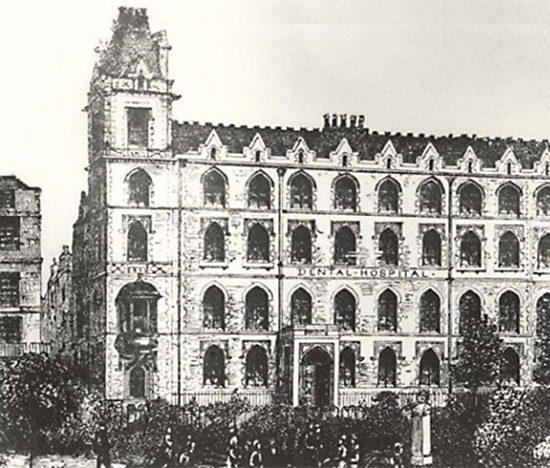

Unlike medical doctors, dentists in England continued to learn their trade by observation of other practitioners or in more formal apprenticeships. To improve professionalism, The Odontological Society was founded on 10 November 1856. Two years later on 1 December 1858, the society founded The Dental Hospital of London at 32 Soho Square (see below), a short ways from the dental manufactory on Broad Street. Another year would pass, before The London School of Dental Surgery was opened on 1 October 1859 as part of the hospital .

Source: Gelbier, S. Dentistry and the University of London, Medical History 4, 1 October 2005, pp. 445-462.

5) If the disease was caused by a living organism, what was the incubation period?

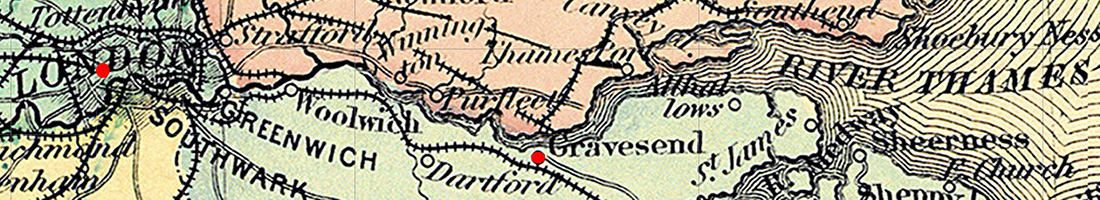

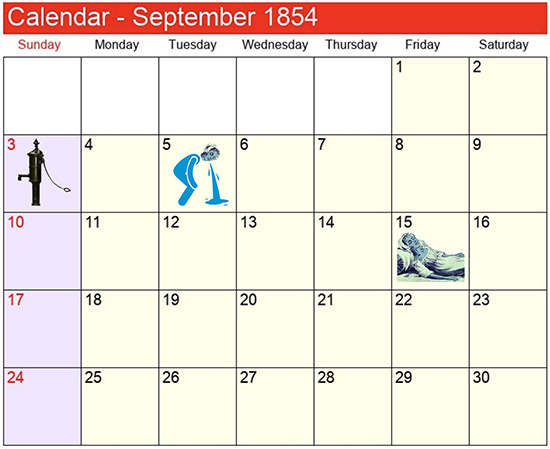

I am indebted to Mr. Marshall for the following cases, which are interesting as showing the period of incubation, which in these three cases was from thirty-six to forty-eight hours. Mrs. -----, of 13 Bentinck Street, Berwick Street, aged 28, in the eighth month of pregnancy, went herself (although they were not usually water drinkers), on Sunday, 3rd September, to Broad Street pump for water. The family removed to Gravesend on the following day; and she was attacked with cholera on Tuesday morning at seven o'clock, and died of consecutive fever on 15th September, having been delivered. Two of her children drank also of the water, and were attacked on the same day as the mother, but recovered.

- Snow J. On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, 1855, page 43.

Bentinck Street is a small street just off Berwick Street. A pregnant woman at 13 Bentinck Street (red dot) who did not usually drink pump water, consumed Broad Street pump water, along with her two children , and all three became sick two days later in 20 mile distant Gravesend (red dot). The period of incubation was between 36 and 48 hours, depending on what time they consumed the contaminated Broad Street Pump water and what time on Tuesday the two children first showed symptoms. This supports Snow's hypothesis regarding the germ theory, namely that cholera is caused by a microbe of some form or another (not yet identified), with an incubation period of a few days, transmitted in water and/or by personal contact.

The time course with cholera of "a pregnant woman at 23 Bentinck Street."

Source:Old Ordnance Survey Maps -- The West End, 1870.

6) Another case provides more information on the length of the incubation period and natural history of the disease.

Dr. Fraser, of Oakley Square, kindly informed me of the following circumstance. A gentleman in delicate health was sent for from Brighton to see his brother at 6 Poland Street, who was attacked with cholera and died in twelve hours, on 1st September. The gentleman arrived after his brother's death, and did not see the body. He only stayed about twenty minutes in the house, where he took a hasty and scanty luncheon of rumpsteak, taking with it a small tumbler of brandy and water, the water being from Broad Street pump. He went to Pentonville, and was attacked with cholera on the evening of the following day, 2nd September, and died the next evening.

- Snow J. On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, 1855, page 44.

A man belatedly came on Friday to the house at 6 Poland Street of his deceased brother who had just died of cholera. After a quick lunch of rumpsteak accompanied by a brandy and water drink (i.e., Broad Street pump water), he left early that Friday afternoon for Pentonville (red dot in 1862 map).

Sources: Old Ordnance Survey Maps -- The West End, 1870, and "Reynold's Map of Modern London, Divided into Quarter-mile Sections for Measuring Distance," Published by James Reynold, 174 Strand St, London, 1862.

The incubation period and natural history of cholera were becoming clear to Snow, even without knowing the specific agent, based on his investigation of the Broad Street Pump outbreak.

On Saturday evening, he came down with cholera, following an incubation period of about 30 hours. Late Sunday, he too died of the disease. What started at the Broad Street pump (black dot, bottom left) via a quick lunch and brandy-water drink on Poland Street (small red dot), ended up in death in Pentonville (red dot).