Stream 2 - Broad Street Pump Outbreak

b: Photo Tour of Snow's London Neighborhood

While much has changed in London during the past many years since the mid 1800's era of Dr. John Snow, quite a few historical buildings and streets remain, with signs posted to guide interested visitors. Presented here are current photos of locations where John Snow lived or worked during his professional life from 1836 until his death in 1858.

JOHN SNOW'S THREE HOMES

Snow's First London Home

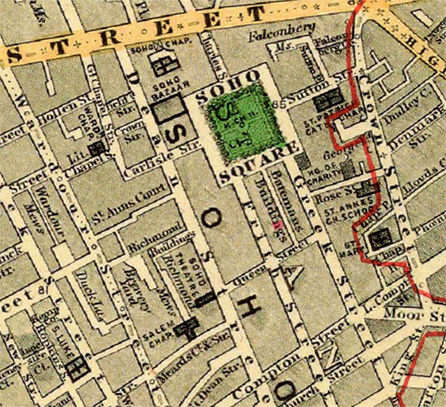

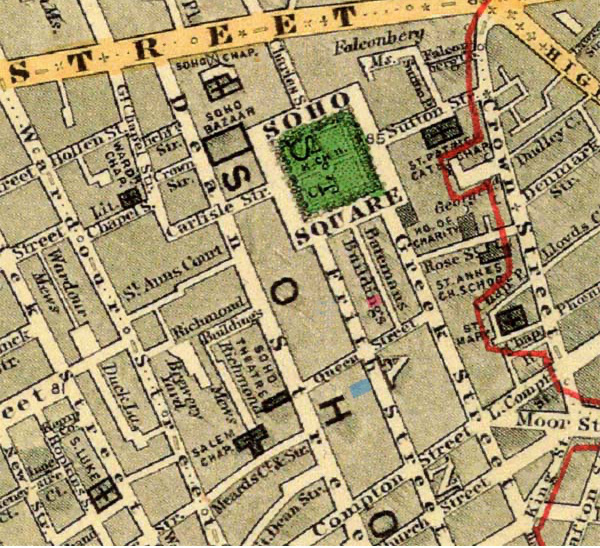

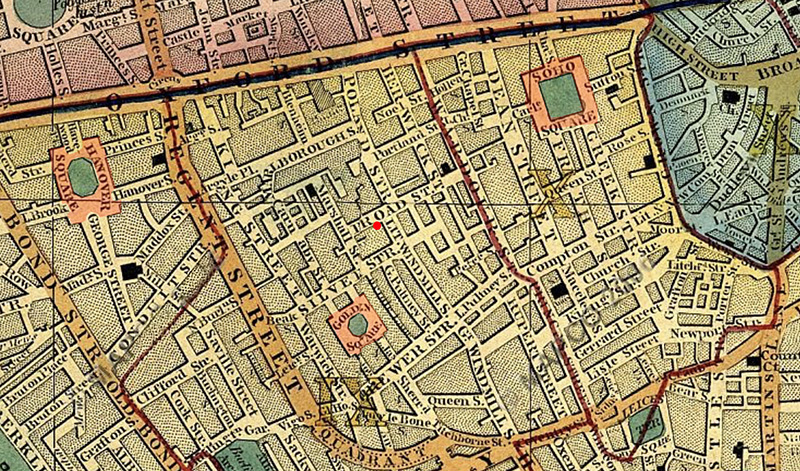

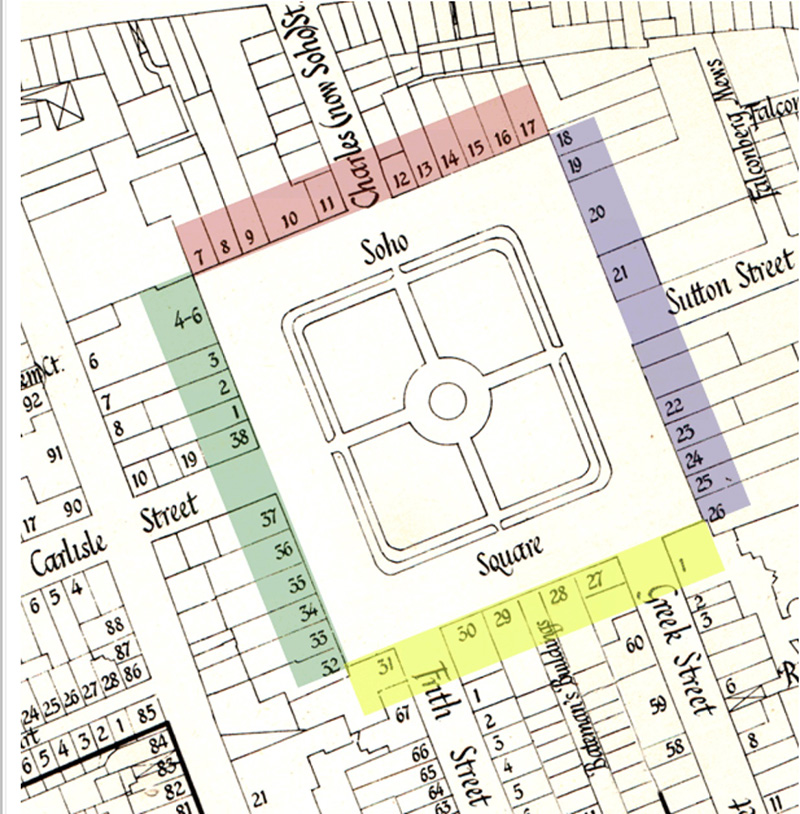

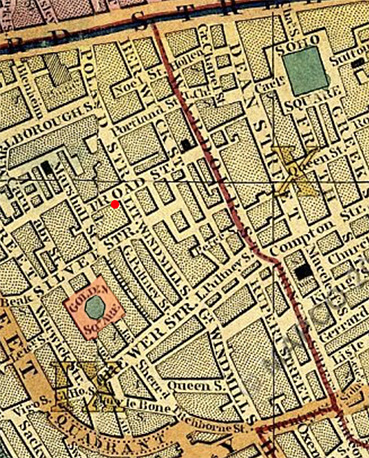

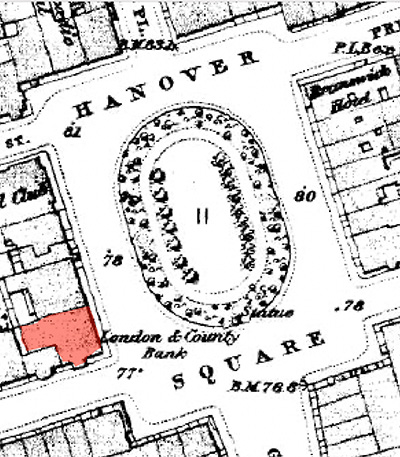

When he first came to London in October 1836 to continue his formal medical education, John Snow lived at 11 Bateman's Buildings, a narrow, nondescript alleyway near Soho Square (see red spot in Stanford's 1862 map).

Snow remained there until 1838 when he started his medical practice. The dwelling where Snow resided was a plain front building, three stories high above a cellar basement and two windows wide.

His living experience was described by historian Stephanie Snow: "Snow's lodgings were situated less than a quarter of a mile away from the Hunterian Medical School and just over a mile away from Westminster Hospital. For most of his student days, he lived at 11 Bateman's Buildings, Soho Square, in lodgings with a fellow medical student at the Hunterian School, Joshua Parsons. Parsons wrote that they had met in the dissecting room: 'it happened that we usually overstayed our fellows, and often worked far on into the evening. The acquaintance thus grew into intimacy, which ended by our lodging and reading together. We were constant companions from that time till I left town in October 1837.' Reading formed a major part of a student's life and had to be fitted into the beginning and the end of the day, as the remainder was taken up by lectures and dissection. There is no doubt that the life of a medical student was rigorous and potentially isolating."

- Stephanie Snow, 2000.

After completing a year at the Hunterian School of Medicine, Snow enrolled in October 1837 in the Westminster Hospital for surgical and medical practice. Thereafter, Snow took the Royal College of Surgeons examination in May 1838 and passed without problem. In September 1838 he moved from his dingy quarters on Bateman's Buildings to a rented house at 54 Frith Street, a short ways away in Soho.

Aside - Hunterian School of Medicine

Aside - Hunterian School of Medicine

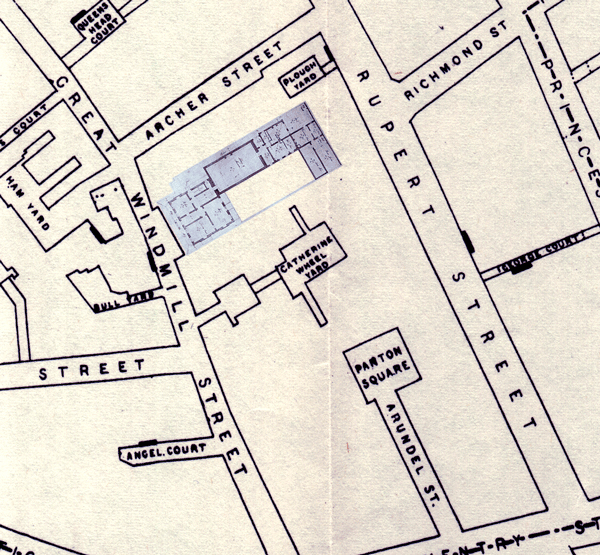

The Hunterian Medical School was founded in 1769 by William Hunter (1718-1783) at his home on Great Windmill Street in the Soho region of London.

William and his younger brother John (at right, 1728-1793) were Scottish pioneers of medicine and surgery, and were enthusiastic collectors of paintings and scientific instruments, much of which is now exhibited at the Hunterian Museum near Glasgow, Scotland.

William Hunter was born in 1718 in Long Calderwood, East Kilbride, near Glasgow, Scotland. He first attended Glasgow University and then studied medicine at Edinburgh.

In 1741 he settled in London, taught anatomy and surgery, and made a special study of the lymphatics and the gravid uterus (i.e., with a developing egg). In 1769 he moved to 16, Great Windmill Street, where he created a museum and the Hunterian School of Medicine.

By 1836 when John Snow arrived in London, the metropolitan area housed 21 schools that offered courses and experience in surgery and medicine. To become a surgeon-apothecary, Snow needed to fulfill the licensing requirements of the Royal College of Surgeons and the Society of Apothecaries. The Hunterian School of Medicine [see below and blue tinge in Cheffins 1854 map at right] was well-known for having dedicated instructors, including John Epps who also was involved in the temperance movement. Finally, the school was the lowest priced among institutions that offered courses necessary for surgeon and apothecary licensure. Being of poor background, the cost likely influenced his decision.

Note: The view below of the Hunterian Medical School is west on Great Windmill Street at No. 16, formerly house and anatomical theater of Dr. William Hunter. It was designed by architect Robert Mylne in 1767 and remained as a medical school until 1838 when it closed, a year after John Snow completed his studies.

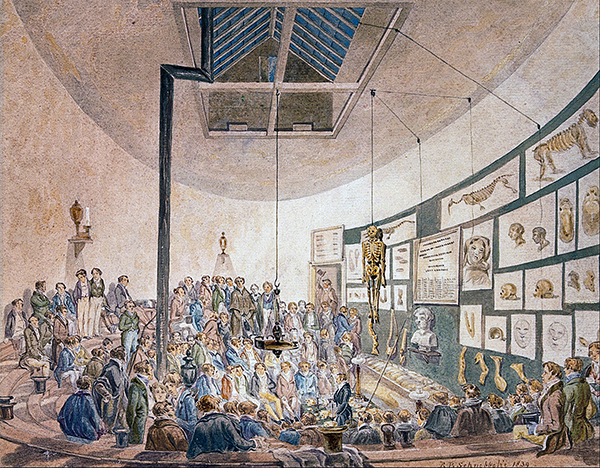

When John Snow attended the Hunterian Medical School in 1836-37, courses were given daily either in six month sessions (chemistry and medical jurisprudence) or three month sessions (anatomy and physiology, practical anatomy and demonstrations [see below], surgery [see below], medicine, and botany). The cost of each course varied from 2-5 pounds. More likely John Snow paid 34 pounds which allowed him to attend all lectures required by the Hunterian Medical School, and any lectures on midwifery that were conducted in the neighborhood near the school.

Source: Schnebbelie, RB. Watercolor. A lecture at the Hunterian Medical School, anatomy class, Great Windmill Street, London, 1839, Wellcome Collection.

Applied anatomy course, Hunterian Medical School, 1838.

The Hunterian Medical School remained active until 1839 when it finally closed its doors after 70 years of existence. The premises have now been demolished, and on its site stands the Lyric Theater (on Great Windmill Street between Archer Street and Shaftesbury Avenue in the Soho region of London).

At the rear portion of the Lyric Theater, a plaque was erected in 1952 that reminds visitors of Dr. William Hunter and his home and museum, but not his medical school, nor his distant connection via his institution to Dr. John Snow.

End of Aside - Hunterian School of Medicine

End of Aside - Hunterian School of Medicine

After having spent a year at the Hunterian School of Medicine, John Snow continued his education by studying clinical subjects during 1837 and 1838 at the Westminster Hospital. He was 24 years old when he started this phase of his medical studies.

Aside - Westminster Hospital

Aside - Westminster Hospital

History from Infirmary to Hospital

The Westminster Hospital has a long and famous history. It was started in 1719 as an infirmary for sick poor people and had about 18 beds. A few years later in 1721, it was replaced by a second infirmary, but this time with 31 beds. Subsequently, this too was replaced with a third infirmary, which lasted from 1735 to 1834. Along the way, the infirmary in 1760 was renamed Westminster Hospital and grew to 98 beds.

In 1827 a new surgeon named George James Guthrie (to the left) came to Westminster Hospital. He had been the foremost military surgeon of his day and was a man of strong opinions. Two factions quickly developed in the hospital, with one siding with Guthrie and the other with his opponents. An argument during Guthrie's first year at the hospital included insulting remarks, which lead to a duel between Guthrie's pupil, Hale Thompson and a member of the opposing group. The two men fired three shots at each other but no hits were scored. Someone suggested as surgeons that perhaps they would have been more deadly with scalpels rather than with pistols. Subsequently, Hale Thompson was cited in The Lancet as "bullet-proof Thompson." John Snow at the time was only 14 years old, but likely heard of the duel.

The New Building of 1834

After Guthrie was at Westminster for a few years, a building fund was started with plans to create a new hospital.

The site (shown in red in Davies map of 1843) was identified on Broad Sanctuary across the street from the Westminster Abbey and a block or two East of the Houses of Parliament and the River Thames. The building was completed in November, 1834. The map of London published in 1869 shows the exact location.

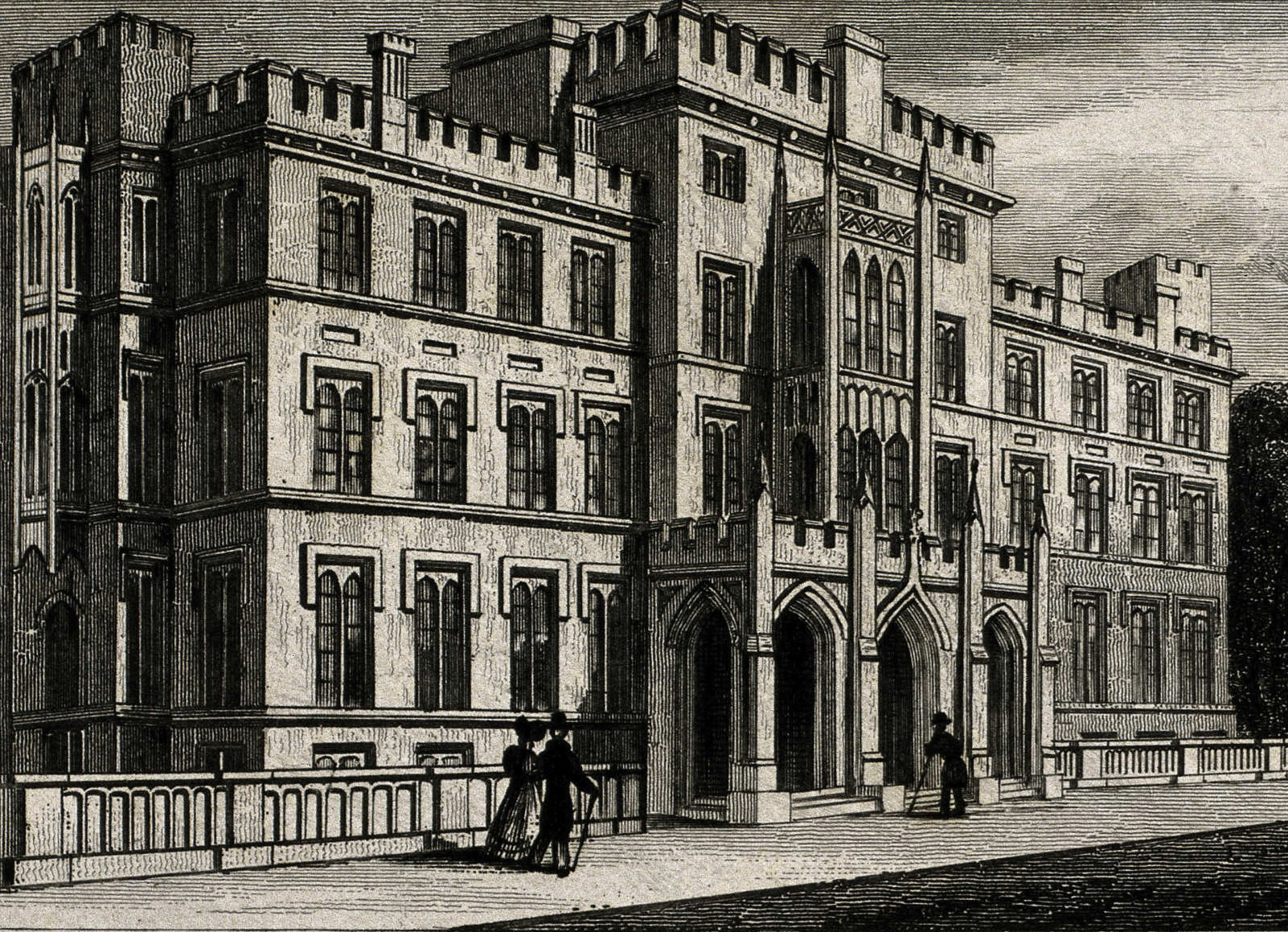

Including the site and new building, the hospital cost 40,000 pounds. At the time, it was considered to be state-of-the art, with each ward having its own water closet (the British term for a bathroom). The new building (shown below) was there to greet John Snow in 1837 when he started his clinical training at age 24. It remained in use as a hospital until 1939, or 81 years after Snow's death.

When the new Westminster Hospital opened in 1834 next to the Westminster Abbey (see below), Guthrie proposed that a school of medicine be started in connection with the hospital. This was violently opposed by his colleagues, but fortunately no one suggested another duel. Soon thereafter the private Westminster School of Medicine was started, and in 1841 was incorporated as an official medical school attached to the hospital.

By 1841, John Snow had already completed his two years of clinical training (1837-38) and passed his licensing exams to administer and sell therapeutic drugs and practice medicine (then listed as "John Snow, M.R.C.S., or Member of the Royal College of Surgeons ). Thus, while attending clinical rounds at the Westminster Hospital, he never formally enrolled in the Westminster School of Medicine. Nevertheless, he was viewed by many as a "Westminster man" and latter praised for having put anesthesia on a sound scientific basis and for his studies of the epidemiology of cholera.

The Westminster Hospital that felt the footsteps of John Snow is now but a distant memory. The building was demolished in 1950 along with another building, and replaced in 1986 with the Queen Elisabeth II Conference Center (seen below).

End of Aside - Westminster Hospital

End of Aside - Westminster Hospital

Sources:

Davies BR. London 1843, Publisher: Chapman and Hall, 186 Strand, London, Nov. 1, 1843.

Jones E, Sinclair DJ. Atlas of London and the London Region, 1968.

Humble JG. British Medical Journal 1, 156-162, 1966.

Humble JG, Hansell P. Westminster Hospital 1716-1974, 1974.

Snow, Stephanie J. John Snow MD (1813–1858). Part II: Becoming a doctor - his medical training and early years of practice. Journal of Medical Biography 8(2), May 2000.

Watson I. Westminster and Pimlico Past, 1993.

Westminster Hospital with Westminster Abbey,1842, London Metropolitan Archives.

Snow's Second London Home

At age 25 after becoming certified as a general medical practitioner, John Snow moved in May 1838 to a rental home at 54 Frith Street (blue spot on Stanford's 1862 map below, image at right), where he lived for fourteen years until 1852.

Sharing the rental dwelling (1841 census) were John Snow, his 30-year old foreign born housekeeper Jane Wetherburn, and the owner of the building, Mrs. Williamson and her 30 year old daughter.

Nothing remains of the original building, now on restaurant row. A blue plaque over the door describes the site as the location of the prior home of Dr. John Snow.

Shortly after moving to 54 Frith Street, John Snow in October 1838 took and passed the examination of the Society of Apothocaries. Earlier in May he had passed the examination of the Royal College of Surgeons. With these two licenses Snow was fully qualified to serve as a medical practitioner. Unfortunately, his private practice was at first not very profitable and he lived a very frugal life, including payment for his rental home at 54 Frith Street. Nevertheless, he had suffient funds to hire housekeeper Jane Wetherburn who remained with him as a live-in domestic worker for two decades until he died in 1858. According to the 1841 Census, Wetherburn was 27 years old when she was hired in 1838.

Snow did not become established in his profession until the late 1840s, owing to his growing reputation in the specialty of anesthesiology. Starting in 1839, he had also become an active member of the Westminster Medical Society, joining medical and public health discussions held at Westminster Hospital. This, along with his early publications and specialization, helped develop his fame. During these early years he also returned to school, obtaining his MD degree from the University of London in 1844. Finally in 1850 at age 37 he took and passed the licensing examination of the Royal College of Physicians, placing him among those highly qualified in his profession. Late in 1852, having become successful and much wealthier, Dr. John Snow moved to a more fashionable home at 18 Sackville Street, where he remained until his death.

The street that John Snow had moved to in 1838 was named for Richard Frith, the main developer in 1678 when building first got underway. The pace of development increased in the eighteenth century, including Snow's rental home, with a combination of residents and businesses. Shop fronts were a common sight on the street. In late 1852 when Snow moved to his third London address at 18 Sackville Street, few of the Frith Street buildings he left behind were solely personal residences. Instead, most were mixtures of rentals and small businesses, such as tailors or dressmakers, goldsmiths, jewelers and watchmakers.

While there is no coomplete image of Snow's 54 Frith rental home, there is a partial image in a painting of 55 Frith Street created in 1891 at the corner of Frith and Queen streets. Half of Snow's 54 Frith Street home is seen to the left of 55 Frith Street.

Snow's Third London Home

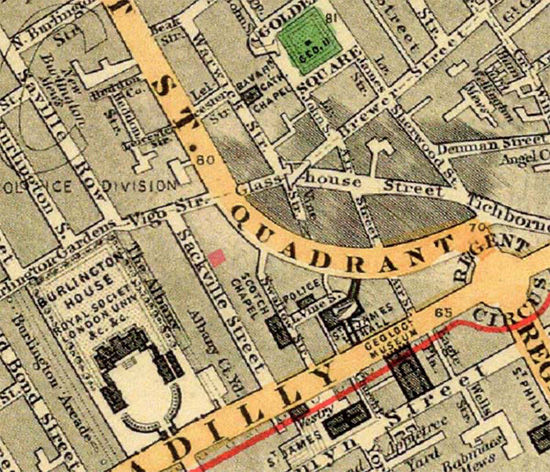

At age 39 in 1852, John Snow moved again, but this time to a more affluent region of the city. The Regent Street area to the west of Golden Square had become ultra-fashionable, offering both expensive items, and elegant homes for those who could afford them. Dr. Snow was becoming increasingly prominent, both as a medical scientist and an anesthesiologist, and likely had a good income. He left his Frith Street home in 1852 and moved to 18 Sackville Street (see red dot below), where he remained until his death in 1858. Sackville Street was home to Dr. John Snow during his historic investigations of the Broad Street Pump Outbreak (1854) and Grand Experiment (1854), and when serving as anesthesiologist to Queen Victoria (1853 and 1857.

Sackville Street was originally laid out in 1670s but was cleared in 1731, making way for a major reconstruction with fine houses on deep and wide plots on the west side and smaller plots for standard houses on the east side (where Dr. Snow lived, see below ). Building was completed in 1733. The edifices remained similar in style until the 1960s when some of the buildings were demolished (as was Snow's former home in 1965) and others were altered. Many of the homes were also heightened over the years with addition of an attic.

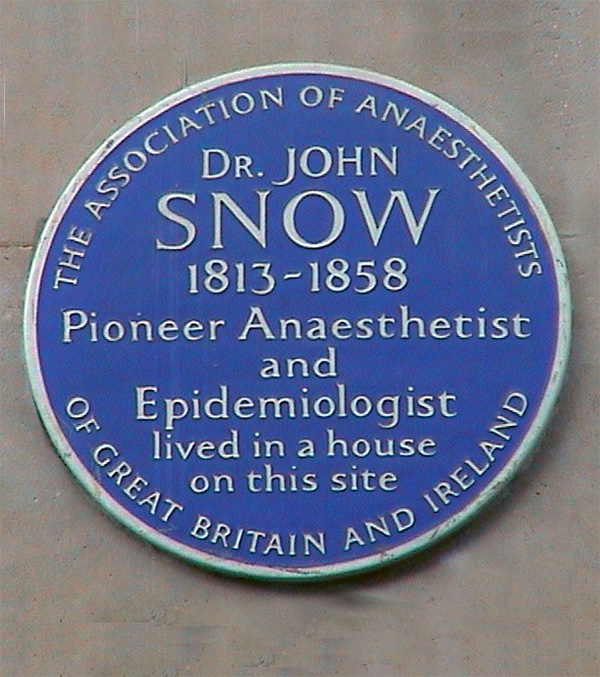

Long after Snow lived at 18 Sackville Street, his final home, he was honored in 1949 with a round plaque, placed in front between the two windows by the London County Council. It read John Snow,1813-1858, physician and specialist anaesthetist who discovered that cholera is water-borne, lived here.

Both the building and the plaque were destroyed in 1965.

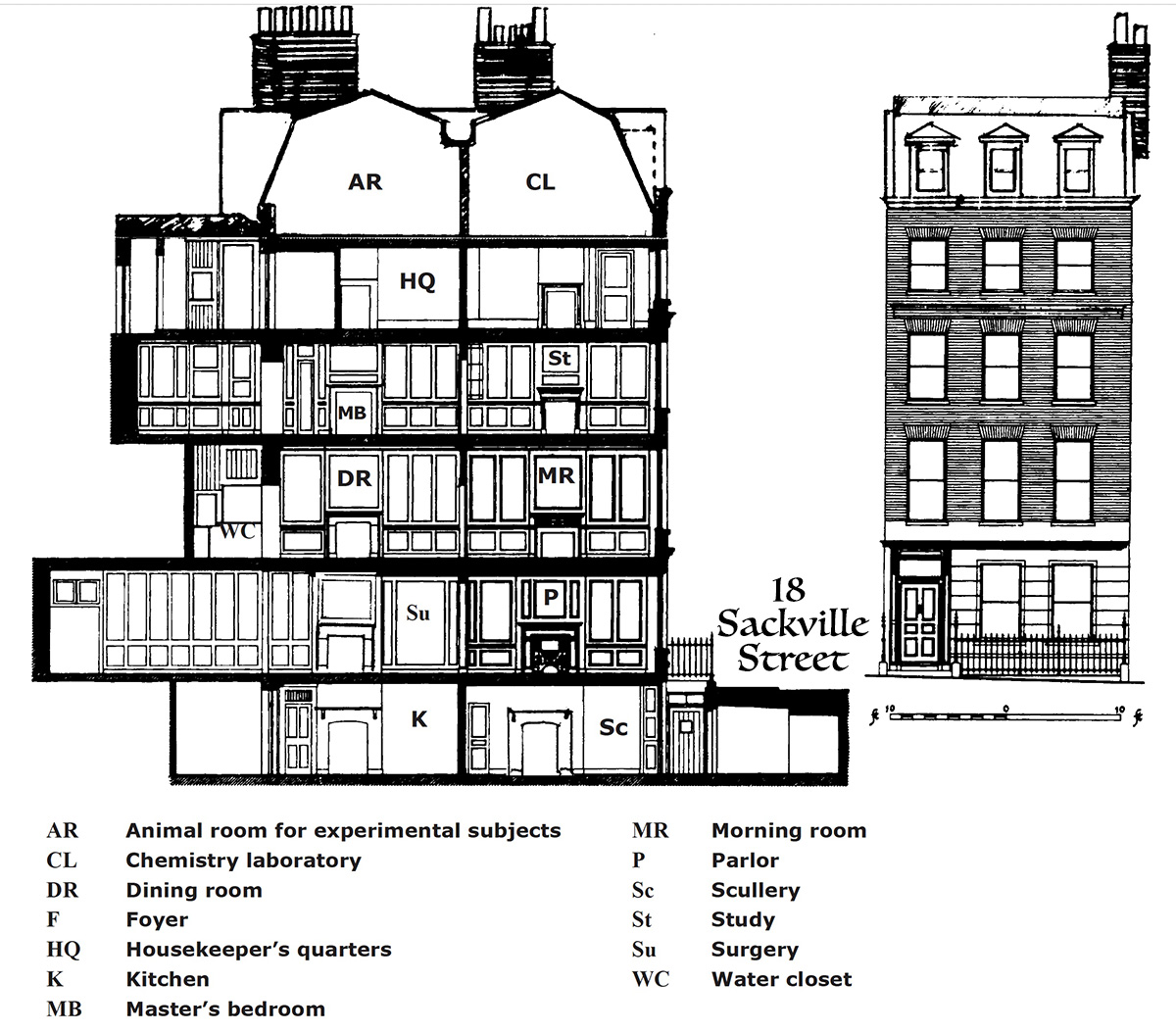

Further detaiils of Snow's Sackville home were created by Peter Vinten-Johansen of the John Snow Archive and Research Companion who used available architectural information on a neighboring house and other details to reconstruct the likely elements of 18 Sackville Street. These included the chemistry laboratory and animal room for experimental subjects on the top floor, and Dr. Snow's surgery (the room where he attended patients) on the street-level floor, directly behind the parlor.

The housekeeper's quarter was occupied by his long-term housekeeper Jane Wetherburn, who moved with him from 54 Frith Street.

At the current 18 Sackville Street address, there is no building nor even a plaque to commemorate that Dr. Snow lived there. Instead, the site is now an eloquent store which occupies 16-21 Sackville Street, noted below. Snow's sole occupancy blue plaque remains at 54 Frith Street, his secnd home.

JOHN SNOW'S NEIGHBORHOOD - SQUARES

Three squares outlined in red hue (Soho, Golden and Hanover), or small urban parks, were often visited by Dr. Snow during his life, including the troubled pump on Broad Street (red dot). The squares identified the region of the city, and gave special character to the various neighborhoods.

Soho Square

Soho Square is south of Oxford Street and west of Charing Cross Road, on the north-eastern extremity of the Soho region. It is just outside the neighborhood identified by Dr. Snow in his classic investigation of the Broad Street pump outbreak, and is also close to his first two homes.

The square was laid out in the 1680's and called 'King Square' in honor of Charles II (1630 – 1685), with his statue at the centre of the gardens. The statue was later removed and a small Tudor-style house was erected on the site, at first descending to an electricity sub-station constructed under the gardens, but later becoming a gardener’s shed. In 1938 the statue of Charles II was restored to the square and stands nearby.

John Snow was an avid walker, having traveled by foot through many regions of England. No doubt he enjoyed walking in Soho Square, the closest open area to his first two homes on Bateman's Buildings (red spot) and Frith Street (blue spot). He likely entered the Square via Frith Street (green dot),

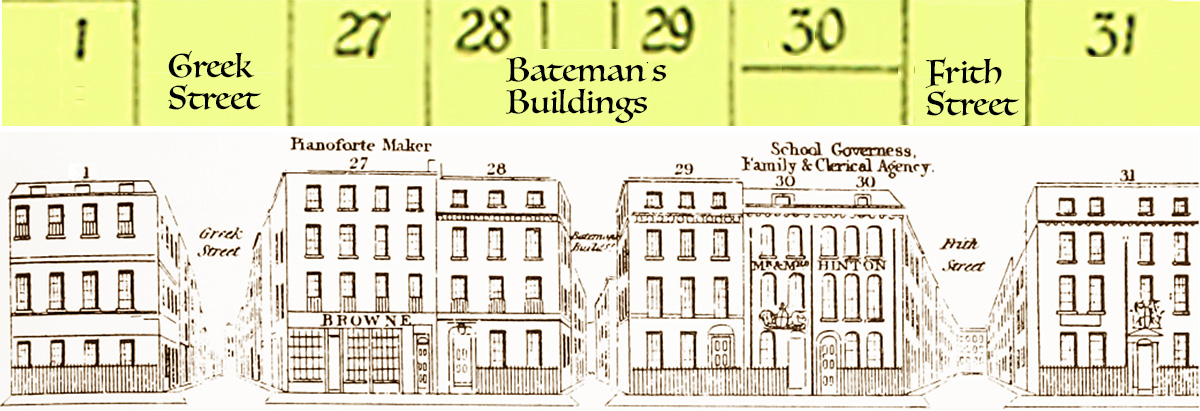

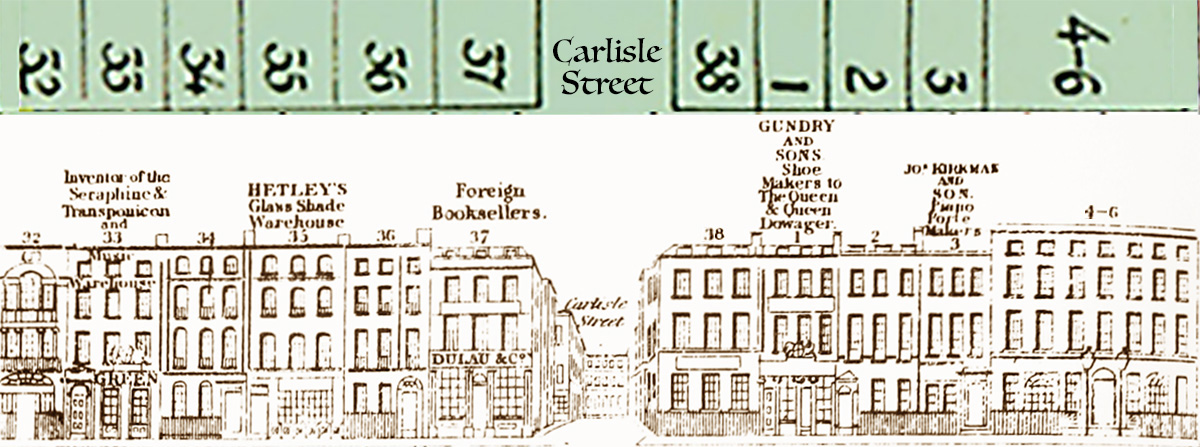

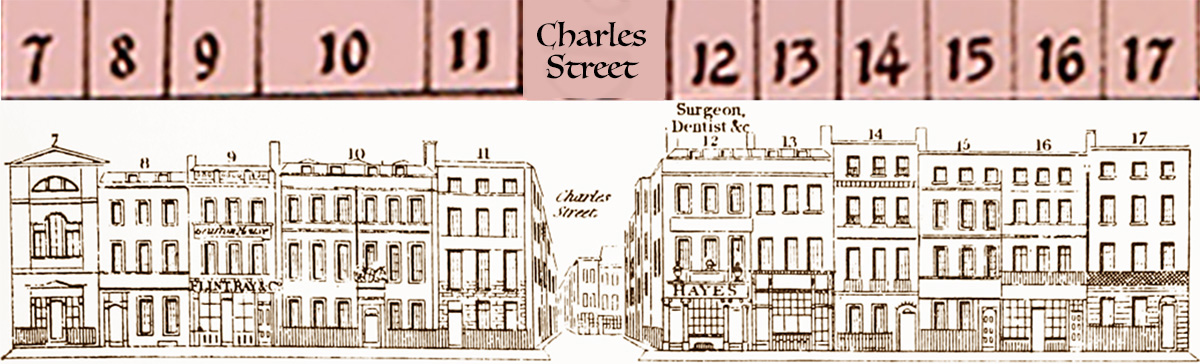

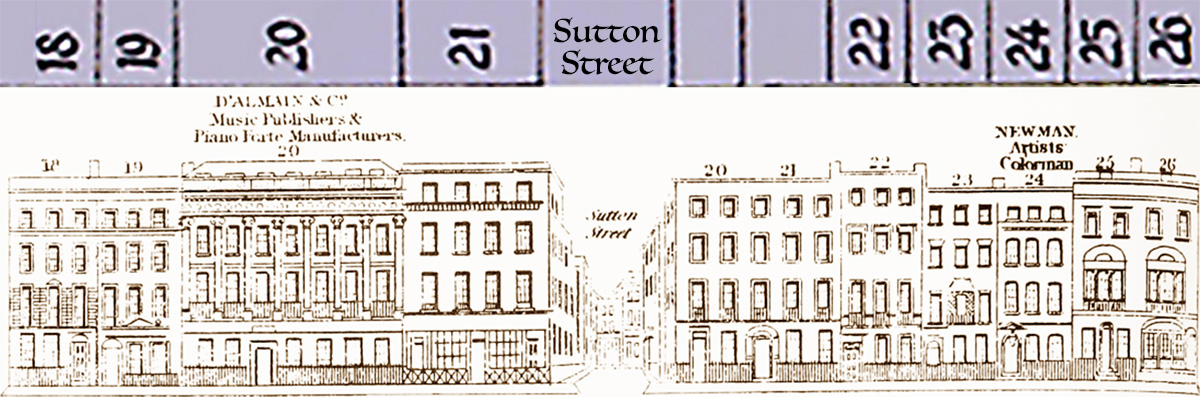

Using 1838-40 images and an 1869-74 Ordnance Survey with street numbers, we see what Snow saw when strolling around Soho Square.

The view in 1838-40 is of Soho Square's south side. The military recruiting office for the East India Company was at #28. Bateman's Building where John Snow first lived is the center intersection, while Frith Street where he lived subsequently is the intersection towards the right. In 1851-52, #30 was taken over by the Hospital for Women.

The view in 1838-40 is of Soho Square's west side.The front section of #32 was leased to the Linnean Society of London. About two decades later in 1858 (the year of John Snow's death), #32 would become the site of the first dental hospital in England, the Dental Hospital of London. The J. Green music warehouse was at #33 and George Routledge, publisher, lived at #36. Father and Son Kirkman, piano makers, had their business at #3.

The view in 1838-40 is of Soho Square's north side. Silk and linen were sold at #9, while Joseph Hayes, a dentist, had his shop at #12.

The view in 1838-40 is of Soho Square's east side. A firm of musical instrument makers was at #20. H.D. Jones, a surgeon, lived at #23. Thomas Barnes, editor of The Times lived at #25. From 1851-56, Rev. Henry Whitehead, rented room B in #21. He had accepted a post as curate in 1851 at nearby St. Luke's Church and a few years later had become senior curate. This was his residence while assisting Dr. John Snow with the 1854-55 investigation of the Broad Street Pump Outbreak. As seen below, the facade of his building, among the few in Soho Square, has not changed much over the years.

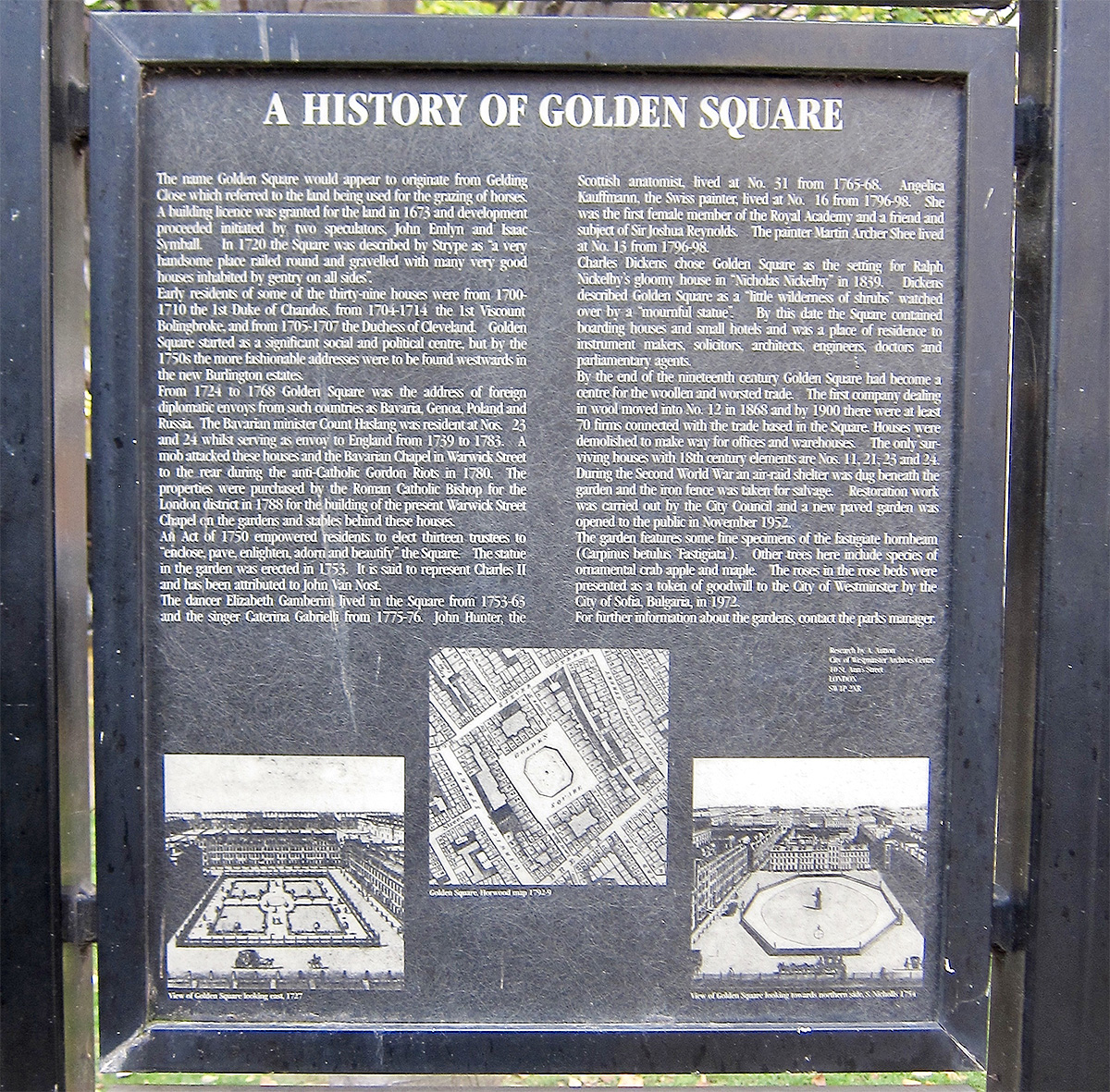

Golden Square

The Golden Square is east of Regent Street and north of Piccadilly Circus. It is a few blocks from the Broad Street pump (red dot) where cholera cases were common, but experienced few cholera cases during the famous 1854 outbreak, due perhaps to higher quality water in the pumps that served the area. At the center of the square is a statue of George II (1683-1760), King of Britain and Ireland from 1727 until his death in 1760. The statue was sculpted in the 1720s for the Duke of Chandos (a former Square resident) and moved to the Square in 1753. The square is also dotted with modern skulpture, including "Stiletto Heel" by Kalliopi Lemos, there since 2016.

A sign at the entrance to the square tells of the history

Hanover Square

Hanover Square lies west of Regent Street and south of Oxford Street, outside by a short distance of the Soho region. It was here in 1850 that Dr. Snow and others met to form the Epidemiological Society of London, in the building shown in red on the 1869-80 Ordnance survey map and in the recent photo from inside Hanover Square (red building with white first level on the left).

There is one statue deserving mention in Hanover Square, a bronze honoring William Pitt the Younger (1759-1806, his father William Pitt was also prominent) former Prime Minister of Great Britain and then the United Kingdom. Beyond the bottom left of the statue is the top level of the red building where the Epidemiological Society of London held its meetings.

During Napoleon Bonaparte's (1769-1821) rise to Emperor in France, William Pitt was an important player in limiting Napoleon's ascending world power. The premier political cartoonist of his time, James Gillray (1756-1815), published his views in 1805 of the two giants with "The Plumb Pudding in Danger," carving up spheres of influence in the wider world.

Aside - Epidemiological Society of London

Aside - Epidemiological Society of London

Epidemiological Society of London

John Snow was a founding member of the Epidemiological Society of London, one of the first professional organizations devoted to the field of epidemiology. The seal of the organization (see figure) includes the Latin phrase penned by the Roman poet Persius (34-64 AD), venienti occurrite morbo, translated into English as confront disease at its onset. How did this important movement get started? What were their contributions during Snow's life, and in the years that followed?

ORIGIN OF SOCIETY

In February 1848, three and a half years after John Snow received his M.D. degree, an intriguing letter to the editor appeared in The Lancet. England at the time was very concerned with the possible appearance of a second cholera epidemic (the first ever occurred in 1831-32). The letter started, "Will that dreadful scourge the cholera visit our island again? If so, are medical men prepared to wage a war against it?" The letter proceeded to suggest that "meetings [to address this disease] should be held in different localities." Finally the letter concluded with the suggestion that medical journals should report "a statistical account of deaths and recoveries." The signer was mysteriously identified as "Pater" (a British term for father).

In July 1849, after cholera had again appeared in England, the same Pater wrote once more to The Lancet, but this time to propose "...the formation of a new society, which might be styled the Asiatic-Cholera Medical Society, or the Epidemic Medical Society, the object of which would be to investigate epidemics..."

The identity of Pater was finally revealed in The Lancet as J. H. Tucker, a concerned physician practicing in London. His stimulating words lead to a meeting on March 6, 1850 in Hanover Square, within walking distance of the Broad Street pump in the Soho region of London. It was here that the Epidemiological Society of London was born, in the building at 21 Hanover Square W1 (red dot and below). The building had just been remodeled, later in 1859 housing the London and County Banking Company of London.

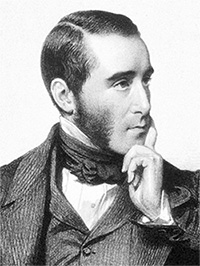

A second meeting was held in the same building in Hanover Square on July 30, 1850 to create a constitution and appoint the founding members and officers. The first president was Dr. Benjamin G. Babington (at right), a prominent physician at Guy's Hospital in London and member of the medical board that was expected to advise the London government on ways to address the cholera epidemic. John Snow also attended this organizing meeting of the Epidemiological Society of London and is considered one of the founding members. He was 37 years old.

After another four months had past, Dr. Babington held on December 2, 1850 the first professional meeting of the Epidemiological Society of London, 33 months after the initial Pater letter appeared in The Lancet. About 100 members and visitors were present. Among the most famous were Thomas Addison (1793-1860), the British physician who discovered pernicious anemia (now termed Addison's anemia) and adrenal cortex deficiency (now called Addison's disease); and Richard Bright (1789-1858), his British colleague who first described the disease characterized by edema and presence of albumin in urine, now termed Bright's disease. For others, including John Snow, fame would come later. Notable in this latter group was Dr. John Simon John Simon (1816-1904) (at left), who in 1848 had become the first medical officer of health of London (he remained in that position until 1855); and Gavin Milroy (1805-1886) who in 1864 on Babington's retirement, would become the second president of the Epidemiological Society of London.

ORIGINAL PURPOSE OF THE ORGANIZATION

When the constitution of the Epidemiological Society of London was created, the founders had three major purposes all related to epidemics as a broad notion, not specific to a cholera epidemic, the threat of which had stimulated the earlier letters of Pater.

1) to institute rigid examination into the causes and conditions which influence the origin, propagation, mitigation, and prevention of epidemic diseases;

2) to institute...original and comprehensive researches into the nature and laws of disease; and

3) to communicate with government and legislature on matters connected with the prevention of epidemic diseases.

The founders also recognized that having ideas without public or professional communication is a self-centered undertaking. To avoid this end they advocated:

1) to publish original papers;

2) to issue queries;

3) to publish reports;

4) to form statistical tables;

5) to prepare illustrative maps; and

6) to collect works relative to epidemic diseases.

These purposes and undertakings remain appropriate today.

1) to institute rigid examination into the causes and conditions which influence the origin, propagation, mitigation, and prevention of epidemic diseases;

1) to publish original papers;

Papers were regularly presented at the monthly meeting of the Epidemiological Society of London such as one in 1851 on the use of statistics and statistical methodology in the study of epidemic diseases. Between 1851 and 1853, most meetings had considerable discussion about whether or not a specific disease was caused by a contagion, cholera and yellow fever being common examples cited by both opponents and proponents of the germ theory (i.e., disease is caused by a microorganism or germ).

In 1853, John Snow (at right) presented a paper on "The Comparative Mortality of Large Towns and Rural Districts, and the Causes by Which it is Influenced" which featured the application of statistics to epidemiology.

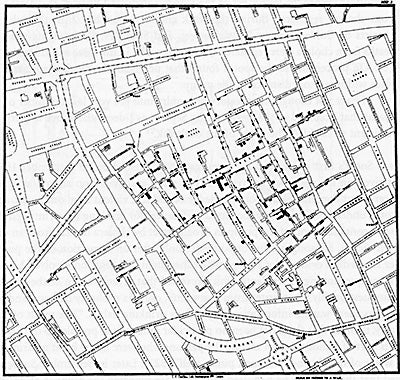

On December 4, 1854, Snow presented to the Society an early version of a map of the Broad Street Pump outbreak (at left), showing deaths from cholera in the different houses in the neighborhood of Golden-square, together with a statistical table, exhibiting the dates of attack and the like. The map with some additional changes would appear as Map 1 in his coming book, published months later in 1855. Handed around to the members, the map showed that the greatest number of attacks occurred on the 1st of September, and that the most deaths were in the neighbourhood of the Broad-street pump.

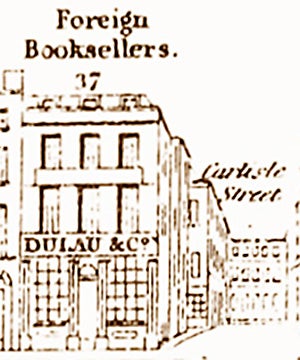

Because of a scheduling conflict at Hanover Square, the meeting was held in the Foreign Booksellers building at 37 Soho Square by Carlisle Sreet(at right).