Return to John Snow Publications

Return to John Snow Publications

31. "The fatal chloroform case at Newcastle,"

31. "The fatal chloroform case at Newcastle,"

Source: Snow, John. Lancet 1, 26 February 1848, p. 239 [Letter to Ed.].

To the Editor of the Lancet

Sir,--The recent fatal case of inhalation of chloroform appears to confirm in a melancholy manner the remarks contained in my paper in the Lancet of the 12th instant, respecting the danger arising from the cumulative property of the agent when administered on a handkerchief. The alarming symptoms came on after the cloth with chloroform was removed from the patient's face. Some of Dr. Simpson's observations on this case confirm the view I have taken. He says -- "I have seen in a few cases such a blanched state of the lips and features come on, under the use of very powerful and deep doses of chloroform, stimulating syncope, and with the respiration temporarily suspended." It may be presumed, that the cases Dr. Simpson has seen were under his immediate superintendence; and this makes the danger still more evident; for if any one could prevent his patient from getting into a state which cannot be looked on therwise than as one of imminent peril, it would be the authority who introduced the agent, and recommended this method of its administration.

On January 10th, two days after I read the remarks at the Westminster Medical Society, respecting the effects of chloroform increasing after the inhalation was left off, M. Sédillot related, in the Academy of Sciences of Paris, that he had observed the pallor, smallness of pulse, feebleness of respiration, and coldness, to augment in an alarming manner after the employment of the chloroform had been discontinued. His observations were reported in the Gazette Médicale of January 15th.

I agree with Dr. Simpson, that it was not advisable to give brandy, or even water -- the more so, as I do not think with him that there was syncope; but that these liquids caused suffocation, filling up the pharynx, and being partially drawn into the larynx, seems improbable. This question, however, can be only determined by those who observed the symptoms at the time of death, and the nature of the froth found in the bronchi afterwards, as there is nothing in the reported evidence of the appearances on dissection which might not be caused by the kind of asphyxia liable to be induced when the effects of chloroform are carried too far; and these appearances are quite incompatible with Dr. Simpson's supposition that there was syncope. Preventing the recovery from syncope would not cause the state of the heart and lungs, which is characteristic of the opposite kind of death--that by asphyxia. In a certain number of those who are drowned, the heart and lungs are not congested, but the contrary, and it is believed by medical jurists, that those persons have fainted on falling into the water.

-- I remain, Sir, your obedient servant,

John Snow.

Frith-street, Soho.

Return to John Snow Publications

Return to John Snow Publications

32. "On narcotism by the inhalation of vapors" (part 1)

32. "On narcotism by the inhalation of vapors" (part 1)

Source: Snow, John. London Med. Gazette 41, 19 May 1848, pp. 850-54 (part 1).

By John Snow, M.D.

[Part 1]

Vapours when inhaled become absorbed. Method of determining the quantity in the blood in different degrees of narcotism. Experiments on animals for this purpose, with chloroform and with ether.

It is generally admitted that ether and chloroform, when inhaled, are imbibed and enter the blood, and this has been proved, as regards ether, in more ways than one. That substance has been detected in the blood of animals that have inhaled it; and I have proved its absorption as follows: -- I passed a tame mouse through the quicksilver of a mercurial trough, into a graduated jar containing air and ether vapour, and, after a little time, withdrew it through the mercury, and introduced it, in the same manner, into a jar containing only air. On withdrawing it, and waiting till the air cooled to its former temperature, I found that the mercury had risen considerably in the first jar, and become depressed to some extent in the second; vapour of ether having been absorbed from one jar and part of it exhaled into the other.

M. Lassaigne* (Comptes Rendus, 8 Mars, 1847; and Med. Gaz. vol. xxxix. p. 968.) endeavoured to ascertain the proportion of ether in the blood in etherization, by comparing the tension of the vapour of serum of the blood before and after inhalation, with that of an aqueous solution of ether in certain known proportions. This method would, no doubt, indicate the quantity of ether in the serum at the time it was examined; but part of the ether would escape from the blood, in the form of vapour, as soon as it came in contact with the air in its exit from the body. He made the quantity of ether in the blood to be 0.0008, or one part in 1250.

Dr. Buchanan† († Med. Gaz. vol. xxxix. p.717.), by considering the quantity of ether expended in inhalation, and making allowance for what is expired, without being absorbed, considered the quantity in the blood of the adult in complete etherization to be not more than half a fluid ounce; and this is, I believe, a pretty correct estimate.

I consider, however, that I have found a plan of determining more exactly the proportions of ether and of other volatile substances present in the blood in the different degrees of narcotism. It consists in ascertaining the most diluted mixture of vapour and of air that will suffice to produce any particular amount of narcotism; and is founded on the following considerations, and corroborated by its agreeing with the comparative physiological strength of the various substances.

When air containing vapour is brought in contact with a liquid, as water or serum of blood, absorption of the vapour takes place, and continues till an equilibrium is established; when the quantity of vapour in both the liquid and air, bears the same relative proportion to the quantity which would be required to saturate them at the temperature and pressure to which they are exposed. If, for instance, the liquid contains one per cent, and would require ten per cent to saturate it, the air will contain three per cent if thirty per cent be the quantity that it could take up. This is only what would be expected to occur; but I have verified it by numerous experiments in graduated jars over mercury. The intervention of a thin animal membrane may alter the rapidity of absorption, but cannot cause more vapour to be transmitted than the liquid with which it is imbued can dissolve. The temperature of the air in the cells of the lungs and that of the blood circulating over their parietes is the same; and, therefore, when the vapour is too dilute to cause death, and is breathed till no increased effect is produced, the following formula will express the quantity of any substance absorbed:--As the proportion of vapour in the air breathed is to the proportion that the air, or the space occupied by it, would contain if saturated at the temperature of the blood, so is the proportion of vapour absorbed into the blood to the proportion the blood would dissolve.

The plan which I adopted to ascertain the smallest quantity of vapour, in proportion to the air, that would produce a given effect, was to weigh a small quantity of the volatile liquid in a little bottle, and introduce it into a large glass jar covered with a plate of glass; and having taken care that the resulting vapour was equally diffused through the air, to introduce an animal so small, that the jar would represent a capacious apartment for it, and wait for that period when the effects of the vapour no longer increase.

Experiments with Chloroform

I will first treat of chloroform, and, passing over a number of tentative experiments, will adduce a few of those which were made after I had ascertained the requisite quantities. The effects produced in these experiments were entirely due to the degree of dilution of the vapour, for the quantity of chloroform employed was, in every instance more than would have killed the animal in a much shorter time than the experiment lasted if it had been conducted in a smaller jar. It is assumed that the proportions of vapour and air remain unaltered during the experiment, for the quantity absorbed must be limited to what the animal can breathe in the time, which is so small a part of the whole that it may be disregarded.

Exp.1. -- A Guinea pig was placed in a jar, of the capacity of 1600 cubic inches, and the cover being moved a little to one side for a moment, 8 grs. of chloroform were dropped on a piece of blotting paper suspended within. The animal remained in the jar twenty minutes, and was not appreciably affected any part of the time.

Exp.2. -- The same Guinea pig was placed in the same jar, on another occasion, and 12 grs. of chloroform were introduced in the same manner, being three-quarters of a grain for each 100 cubic inches. In about six minutes it seemed drunk. It was allowed to remain for seventeen minutes, but did not become more affected; occasionally it appeared to be asleep, but could be disturbed by moving the jar. On being taken out it staggered, and could not find the way to its cage at first, but it recovered in two or three minutes.

Exp.3. -- Two grains of chloroform were put into a jar containing 200 cubic inches; it was allowed to evaporate, and the resulting vapour equally diffused by moving the jar; and then the cover was withdrawn just far enough to introduce a white mouse. After a short time it began to run round continuously in one direction. At the end of a minute it fell down and remained still, excepting a little movement of one or other of its feet now and then. It remained in the same state, and was taken out at the end of five minutes: it flinched on being pinched, tried to walk directly afterwards, and in a minute or so seemed to be completely recovered.

Exp.4. -- A Guinea pig was placed in the jar of 1600 cubic inches’ capacity, and 20 grains of chloroform were introduced, as in the two first experiments, being a grain and a quarter for each 100 cubic inches. In two minutes the Guinea pig began to be altered in its manner. At the end of four minutes it was no longer able to stand or walk, but crawled now and then. After seven minutes had elapsed it no longer moved, but lay breathing as in sleep. It was taken out at the end of a quarter of an hour. It moved its limbs as soon as it was touched, flinched on being pinched, and in four minutes was as active as usual.

Exp.5. -- Three grains of chloroform were diffused in the jar of the capacity of 200 cubic inches, and a white mouse introduced. It was not affected at first, but in less than a minute became drowsy, and at the end of a minute appeared insensible, and did not move afterwards. It was allowed to remain two minutes longer; it breathed naturally, and its limbs were not relaxed. When taken out it was insensible to pinching; it began to recover voluntary motion in two minutes.

Exp.6 -- The same mouse was placed in the same jar on the following day with 3.5 grs., being a grain and three-quarters for each 100 cubic inches. I[t] ran round as before, but fell down in less than a minute, and before the end of the minute ceased to move. It continued breathing in its natural rapid manner till nearly four minutes had expired, when the breathing became very feeble, and immediately afterwards appeared to have ceased. The mouse was taken out just as four minutes had elapsed. It began immediately to give a few deep inspirations at intervals, after which the breathing became natural; it was perfectly insensible to pinching, and did not stand [851/852] for three minutes. At the end of five minutes it seemed to be recovered, but it did not eat afterwards, and it died on the following day. The state of its organs will be mentioned farther on. The stoppage of respiration and impending death did not seem to be the direct effect of the vapour, but the result of continued and very deep insensibility.

Exp.7. -- A white mouse was placed in the same jar, with 4 grs. of chloroform. At the end of a minute it was lying, but moved its legs for a quarter of a minute longer. When four minutes had elapsed the breathing became slow, and it was taken out. It was totally insensible for the first three minutes after its removal, and recovered during the two following minutes.

Exp.8. -- The same mouse was placed in the same jar on the following day with 4.5 grs. of chloroform, being 2 ¼ grs. for each 100 cubic inches. It became more quickly insensible, and at the end of two minutes the breathing was beginning to be affected, when it was taken out. It recovered in the course of five minutes.

Exp.9. -- A white mouse was put into this jar, after 5 grs. of chloroform had been diffused in it, being 2½ grs. to each 100 cubic inches. It was totally insensible in three-quarters of a minute; in a little more than a minute the breathing became difficult, and, before two minutes had expired, the respiration was on the point of ceasing, and it was taken out. The breathing remained difficult for five minutes, but in other five minutes the mouse recovered, and at the end of a quarter of an hour was very active.

It will be remarked that in these experiments, the mice became much more quickly affected than the Guinea pigs. The reason of this is, their quicker respiration and much more diminutive size. In the last experiment, the quantity of vapour was evidently sufficient to arrest the breathing by its direct influence.

It is evident from the second, third, and fourth of the above experiments, that about one grain of chloroform to each 100 cubic inches of air, suffices to induce the second degree of narcotism, or that state in which the correct relation with the external world is abolished, but in which sensation and ill-directed voluntary movements may exist. Now one grain of chloroform produces 0.767 of a cubic inch of vapour of the sp. gr. [specific gravity] 4.2 as given by Dumas; and when it is inhaled, it expands somewhat as it is warmed, from about 60° to the temperature of the body; but it expands only to the same extent as the air with which it is mixed, and therefore the proportions remain unaltered. But air, when saturated with vapour of chloroform at 100°, contains 43.3 cubic inches in 100; and

As 0.767: 43.3 :: 0.0177: 1

So that if the point of complete saturation be considered as unity, 0.0177, or 1-56th, will express the degree of saturation of the air from which the vapour is immediately absorbed into the blood; and, consequently, also the degree of saturation of the blood itself.

I find that serum of blood at 100°, and at the ordinary pressure of the atmosphere, will dissolve about its own volume of vapour of chloroform; and since chloroform of sp. gr. 1.483 is 288 times as heavy as its own vapour, 0.0177 ÷ 288 gives 0.0000614, or one part in 16,285, as the average proportion of chloroform by measure in the blood, in the second degree of narcotism.

From the fifth experiment it appears that a grain and a half per 100 cubic inches of air is capable of producing the third degree of narcotism; and by the sixth and seventh experiments, it is shewn that from a grain and three-quarters to two grains causes a very complete state of insensibility, which cannot be long continued without danger; but I may remark, that four minutes in a mouse represents a much longer period in the human being, in whom the circulation and respiration are so much less rapid. I think we may take two grains as the average quantity capable of inducing the fourth degree, -- the utmost extent of narcotism required, or that can be safely caused in surgical operations; and by the method of calculation above we shall get 0.0354, or 1-28th, as representing the degree of saturation of the blood, and 0.0001228 the proportion by measure in the blood.

A greater quantity than this seems to induce the fifth degree of narcotism, embarrassing the respiration; and two and a half grains have the power of directly stopping the respiratory movements. By calculation we obtain 0.0442, or 1-22nd, as the degree of saturation of the blood which has this effect.

Birds have generally a somewhat higher temperature than most mammalia, and therefore the following five experiments have been separated from the rest; but, in 13 and 14, the thermometer placed under the wing of the linnet, at the end of the experiment, indicated only 100°,--just the temperature in the groin of the Guinea pig when it was removed from the jar in the 4th experiment. These are the only occasions on which it occurred to me to apply the thermometer.

Exp.10. -- 4.6 grs. of chloroform were put into a jar containing 920 cubic inches, by sliding the glass which covered it a little to one side. The jar was moved about to diffuse the vapour; and thus each 100 cubic inches of air contained half a grain. A hen chaffinch was introduced, by again momentarily sliding the cover a little to one side. In less than two minutes it seemed rather unsteady in its walking at the bottom of the jar, but no further effect was produced, although it remained twenty minutes; when taken out, indeed, it did not seem affected. This experiment was repeated on the same bird, and on another chaffinch, and also on a green linnet, with the same result; that is, no decided effect was produced.

Exp.11. -- 9.2 grs. of chloroform were diffused through the air in the same jar, being one grain to each 100 cubic inches; and a chaffinch was put in. In less than two minutes it staggered about, and in two and a half minutes fell down, but still stirred. It did not get further affected, although it remained ten minutes. Sometimes it seemed perfectly insensible, but always stirred when the jar was moved, and occasionally it made voluntary efforts to stand. On being taken out it seemed sensible of its removal; it flinched on being pinched, and quickly recovered.

Exp.12. -- A chaffinch was placed in the same jar with 11.5 grs., being a grain and a quarter for each 100 cubic inches. In less than a minute it began to stagger, and shortly afterwards was unable to stand, but moved its legs and opened its eyes occasionally. It did not get further affected after two minutes had elapsed, although it remained three minutes longer. It seemed aware of its removal, but was not sensible to being pricked. In attempting to walk when placed on the table, immediately after its removal from the vapour, it fell forwards at every two or three steps. In a minute or two, however, it was able to walk.

Exp.13. -- A green linnet was put in the same jar, with 13.8 grs., being a grain and a half to each 100 cubic inches. In a minute it was unable to stand, and in half a minute more ceased to move. It remained breathing naturally, and kept its eyes open. It was taken out at the end of ten minutes, was insensible to having its foot pinched, and began to recover voluntary motion in three minutes.

Exp.14. -- Was performed on the same linnet, two or three days before the last, with a grain and three-quarters of chloroform to each 100 cubic inches, in the same jar.

It was affected much in the same way as detailed above, but was longer in recovering voluntary motion after its removal, at the end of ten minutes.

It will be perceived that these results coincide as nearly as possible with the effects of the same quantities on the Guinea pigs and mice; and I found that when the quantity of chloroform exceeded two grains to the 100 cubic inches, birds were killed very rapidly.

It occurred to me that if this method of ascertaining the amount of vapour in the blood were correct, then a much more dilute vapour ought to suffice to produce insensibility in animals of cold blood; and that experimenting on them would completely confirm or invalidate these views.

The following experiment has been performed on frogs several times with the same result, the temperature of the room being about 55°.

Exp.15. -- 4.6 grs. of chloroform were diffused through the jar of 920 cubic inches capacity, as in Exp. 10. In the course of a few minutes the frog began to be affected, and at the end of ten minutes was quite motionless and flaccid; but the respiration was still going on. Being now taken out, it was found to be insensible to pricking, but recovered in a quarter of an hour. In a repetition of this experiment, in which the frog continued a few minutes longer, the respiration also ceased, and the recovery was more tardy. On one occasion the frog was left in the jar for an hour, but when taken out and turned over, the pulsation of the heart could be seen. In an hour after its removal it was found to be completely recovered.

Now the vapour is absorbed into the blood of the frog at the temperature of the external air, whose point of saturation, therefore, remains unaltered; and as half a grain of chloroform produces 0.383 cubic inches of vapour; and air at 55° will contain, when saturated, 10 per cent. of vapour; 0.0383, or 1-26th, expresses the degree of saturation of the air, and also of the blood of the frog. And this is a little more than 0.0354, or 1-28th, which we considered as the greatest quantity that could with safety exist in the blood. But frogs are able to live without pulmonary respiration, by means of the action of air on the skin: consequently this experiment coincides exactly with the others, and remarkably confirms the accuracy of this method of determining the amount of chloroform in the blood.

At the College of Physicians, on March 29, when I had the honour of shewing the effects of chloroform at Dr. Wilson’s Lumleian Lectures, and briefly explained these views, I conjoined the last experiment and the 10th in the following manner. I introduced a chaffinch, in a very small cage, into a glass jar holding nearly 1000 cubic inches, and put a frog into the same jar, covered it with a piece of glass, and dropped 5 grs. of chloroform on a piece of blotting paper suspended within. In less than ten minutes the frog was insensible, but the bird was unaffected. Then, in order to shew that the effects depended entirely on the dilution of the vapour, another frog, and another small bird, were placed in a jar containing but 200 cubic inches, with exactly the same quantity of chloroform. In about a minute and a half they were both taken out,--the bird totally insensible, but the frog not appreciably affected, as from its less active respiration it had not had time to absorb much of the vapour.

As the narcotism of frogs, by vapour too much diluted to affect animals of warm blood, depends merely on their temperature, it follows that, by warming them, they ought to be put into the same condition, in this respect, as the higher classes of animals; and although I have not raise their temperature to the same degree, I have found that as it is increased, they cease to be affected by dilute vapour that would narcotize them at a lower temperature.

Exp.16. -- I placed the jar holding 920 cubic inches near the fire, with a frog and a thermometer in it; and when the air within reached 75°, 4.6 grains of chloroform were diffused through it. The jar was kept for twenty minutes, with the thermometer indicating the same temperature within one degree. For the first seventeen minutes the frog was unaffected, and only was dull and sluggish, but not insensible when taken out.

(To be continued)

Return to John Snow Publications

Return to John Snow Publications

33. "On narcotism by the inhalation of vapors (part 2)."

33. "On narcotism by the inhalation of vapors (part 2)."

Source: Snow, John. London Med. Gazette 41, 26 May 1848, pp. 893-95 (part 2).

[Part 2]

Experiments with Ether

We will now proceed to consider ether, and will begin with the brief relation of a few experiments, shewing the strength of its vapour required to produce narcotism to various degrees.

Exp. 17. -- Two grains of ether were put into a jar holding 200 cubic inches, and the vapour diffused equally, when a tam mouse was introduced, and allowed to remain a quarter of an hour, but it was not appreciably affected.

Exp. 18. -- Another mouse was placed in the same jar, with three grains of ether, being a grain and a half to each 100 cubic inches. In a minute and a half it was unable to stand, but continued to move its limbs occasionally. It remained eight minutes without becoming further affected. When taken out it was sensible to pinching, but fell over on its side in attempting to walk. In a minute and a half the effect of the ether appeared to have gone off entirely.

Exp. 19. -- A white mouse in the same jar, with four grains of ether, was unable to stand at the end of a minute, and at the end of another minute ceased to move, but continued to breathe naturally, and was taken out at the end of five minutes. It moved on being pinched, began to attempt to walk at the end of a minute, and in two minutes more seemed quite recovered.

Exp. 20. -- Five grains of ether, being two and a half grains to each 100 cubic inches, were diffused throughout the same jar, and a mouse put in. It became rather more quickly insensible than the one in the last experiment. It was allowed to remain eight minutes. It moved its foot a very little when pinched, and recovered in the course of four minutes.

Exp. 21. -- A white mouse was placed in the same jar with six grains of ether. In a minute and a half it was lying insensible. At the end of three minutes the breathing became laborious, and accompanied by a kind of stertor. It continued in the state till taken out at the end of seven minutes, when it was found to be totally insensible to pinching. The breathing improved at the end of a minute; it began to move at the end of three minutes; and five minutes after its removal it had recovered.

Exp. 22. -- The same mouse was put into this jar on the following day, with seven grains of ether, being 3.5 grs. to the 100 cubic inches. Stertorous breathing came on sooner than before; it seemed at the point of death when four minutes had elapsed; and being then taken out, was longer in recovering than after the last experiment.

Exp. 23. -- Two or three days afterwards the same mouse was placed in the jar, with eight grains of ether, being four grains for each 100 cubic inches. It became insensible in half a minute. In two minutes and a half the breathing became difficult, and at a little more than three minutes it appeared that the breathing was about to cease, and the mouse was taken out. In a minute or two the breathing improved, and in the course of five minutes from its removal it had recovered.

The temperature of the mice employed in the above experiments was about 100°. That of the birds in the following experiments was higher, as is stated; and they differ widely from the mice in the strength of vapour required to produce a given effect, although I found but little difference between the mice and the birds, in this respect, in the former experiments on chloroform. And one of the linnets was employed in both sets of experiments. Having seen MM. Dumeril and Demarquay’s statement of the diminution of animal temperature from inhalation of ether and chloroform, before the following experiments were performed, the thermometer was applied at the beginning and conclusion of some of them. I have selected every fourth experiment from a larger series on birds.

Exp. 24. -- 18.4 grs. of ether were diffused through a jar holding 920 cubic inches, being two grains to each 100 cubic inches; and a green linnet was introduced. After two or three minutes it staggered somewhat, and in a few minutes more appeared so drowsy, that it had a difficulty in holding up its head. It was taken out at the end of a quarter of an hour, quite sensible, and in a minute or two was able to get on its perch. The temperature under the wing was 110° before the experiment began, and the same at the conclusion.

Exp. 25. -- Another linnet was placed in the same jar, with four grains of ether to each 100 cubic inches of air. In two minutes it was unable to stand, and in a minute more voluntary motion had ceased. It lay breathing quietly till taken out, at the end of a quarter of an hour. It moved its foot slightly when it was pinched. In three minutes it began to recover voluntary motion, and was soon well. The temperature was 110° under the wing, when put into the jar, and 105° when taken out.

Exp. 26. -- A green linnet was put into the same jar with 55.2 grs of ether, being six grains to the 100 cubic inches. It was insensible in a minute and a half, and lay motionless, breathing naturally, till taken out at the end of a quarter of an hour. It moved its toes very slightly when they were pinched with the forceps, and it began to recover voluntary motion in two or three minutes. Temperature 110° before the experiment, and 102° at the end.

Exp. 27. -- A linnet was placed in the same jar, containing eight grains of ether to each 100 cubic inches. Voluntary motion ceased at the end of a minute. The breathing was natural for some time, but afterwards became feeble, and at the end of four minutes appeared to have ceased; and the bird was taken out, when it was found to be breathing very gently. It was totally insensible to pinching. The breathing improved, and it recovered in four minutes.

Exp. 28. -- 0.2 grs. of ether, being one grain to each 100 cubic inches of air, were diffused through the jar holding 920 cubic inches of air, and a frog was introduced. At the end of a quarter of an hour it had ceased to move spontaneously, but could be made to move its limbs, by inclining the jar so as to turn it over. At the end of half an hour voluntary motion could no longer be excited, and the breathing was slow. It was removed at the end of three-quarters of an hour, quite insensible, and the respiratory movements being performed only at long intervals, but the heart beating naturally; and it recovered in the course of half an hour. The temperature of the room was 55° at the time of this experiment.

We find from the 18th experiment, that a grain and a half of ether for each 100 cubic inches of air, is sufficient to induce the second degree of narcotism in the mouse; and a grain a half of ether make 1.9 cubic inches of vapour, of sp. gr. [specific gravity] 2.586. Now the ether I employed boiled at 96°. At this temperature, consequently, its vapour would exclude the air entirely; and ether vapour in contact with the liquid giving it off, could only be raised to 100° by such a pressure as would cause the boiling point of the ether to rise to that temperature. That pressure would be equal to 32.4 inches of mercury, or 2.4 inches above the usual barometrical pressure; and the vapour would be condensed somewhat, so that the space of 100 cubic inches would contain what would be equivalent to 108 cubic inches at the usual pressure. This is the quantity, then, with which we have to compare 1.9 cubic inches, in order to ascertain the degree of saturation of the space in the air-cells of the lungs, and also of the blood; and by calculation, as when treating of chloroform,

1.9 is to 108 as 0.0175 is to 1.

So that we find 0.0175, or 1-57th, to be the amount of saturation of the blood by ether necessary to produce the second degree of narcotism; and as by Exp. 21, three grains in 100 cubic inches produced the fourth degree of narcotism, we get 0.035, or 1-28th, as the amount of saturation of the blood in this degree. Now this is within the smallest fraction of what was found to be the extent of saturation of the blood by chloroform, requisite to produce narcotism to the same degree. But the respective amount of the two medicines in the blood differs widely; for whilst chloroform required about 288 parts of serum to dissolve it, I find that 100 parts of serum dissolve 5 parts of ether at 100°; consequently 0.05 x 0.0175 gives 0.000875, or one part in 1142, as the proportion in the blood in the second degree of narco-[894/895]tism, and 0.05 x 0.035 gives 0.00175, or one part in 572, as the proportion in the fourth degree.

In Exp. 28, the frog was rendered completely insensible by vapour of a strength which was not sufficient to produce any appreciable effect on the mouse in Exp. 17. This is in accordance with what was met with in the experiments with chloroform. Air, when saturated with ether at 55°, contains 32 grains; so that the blood of the frog might contain 1-32d part as much as it would dissolve, which, although not quite so great a proportion as was considered the average for the fourth degree in the mice, yet was more than sufficient to render insensible the mouse in Exp. 20.

There is a remarkable difference between the birds and the mice in respect to the proportions of ether and air required to render them insensible, a difference that was not observed with respect to chloroform. In some experiments with ether on Guinea pigs, which are not adduced, they were found to agree with mice in the effects of various quantities.

The birds were found to require nearly twice as much: five grains to 100 cubic inches, the quantity used in an experiment between the 25th and 26th, which is not related, may be taken as the average for the fourth degree of narcotism in these birds, with a temperature of 110°. By the kind of calculation made before, we should get a higher amount of saturation of the blood than for the same degree in the mice. But as serum at 110° dissolves much less ether than at 100°, the quantity of this medicine in the blood of birds is not greater than in that of other animals; and considered in relation to what the blood would dissolve at 100°, the degree of saturation is the same.

By Expts. 22, 23, and 27, we find that with ether as with chloroform, a quantity of vapour in the air somewhat greater than suffices to induce complete narcotism has the effect of arresting the respiratory movements. The exact amount which has this effect might be determined if necessary.

Before proceeding to consider some other vapours, and the general conclusions to be drawn from these inquires, it may be as well to consider how far the above results coincide with experience as to the quantities of chloroform and ether required to produce insensibility in the human subject.

The blood in the human adult is calculated by M. Valentin to average about 30 pounds. This quantity would contain 26 pounds five ounces of serum, which, allowing for its specific gravity, would measure 410 fluid ounces. This being reduced to minims, and multiplied by 0.0000614, the proportion of chloroform in the blood required to produce narcotism to the second degree, gives 12 minims as the whole quantity in the blood. And to produce narcotism to the fourth degree we should have twice as much, or 24 minims. More than this is used in practice, because a considerable portion is not absorbed, being thrown out again when it has proceeded no further than the trachea, the mouth and nostrils, or even the face-piece. But I find that if I put twelve minims into a bladder containing a little air, and breathe it over and over again, in the manner of taking nitrous oxide, it suffices to remove consciousness, producing the second degree of its effects.

In order to find the whole quantity of ether in the blood, we may multiply 410, the number of fluid ounces of serum, by 0.000875 for the second degree, and by 0.00175 for the fourth degree, when we shall obtain 0.358 and 0.71 of an ounce, i.e. foz ij. ɱl. [2 fluid ounces + 50 minims] in the first instance, and foz v. ɱxl. [5 fluid ounces + 40 minims] in the second,--quantities which agree very well with experience when we allow for what is expired without being absorbed.

(To be continued.)

Return to John Snow Publications

Return to John Snow Publications

34. "On narcotism by the inhalation of vapors (part 3)."

34. "On narcotism by the inhalation of vapors (part 3)."

Source: Snow, John. London Med. Gazette 41, 23 June 1848, pp. 1074-78 (part 3).

By John Snow, M.D.

[Part 3]

Experiments to determine the quantity in the blood, and illustrate the action of nitric ether, bisulphuret of carbon, and benzin.

Nitric ether, or nitrate of the oxide of ethyle, consists of nitric acid combined with ordinary or sulphuric ether. It is described as a colourless liquid of sp. gr. [specific gravity] 1.112, with a sweet taste and pleasant smell, and boiling at 185° Fah. Two specimens of it which I have answer to this description. One was made and presented to me by Mr. Bullock; and the other, which was made by Mr. Joseph Spence, was given to me by Dr. Barnes. Dr. Chambert, of Paris, related some experiments that he had performed on dogs with the vapour of this substance, in a work on Ether, published in autumn last; and Dr. Simpson afterwards mentioned it in his pamphlet on Chloroform, as one of the things that he had tried.

The two following experiments will serve to determine the quantity of nitric ether in the blood, when insensibility is induced by it: --

Exp. 29. -- Four grains were diffused through the air in a jar containing 800 cubic inches; and a common mouse was introduced in the same manner as in the preceding experiments. In ten minutes it became rather torpid, but could be disturbed by touching the jar. It was left in this condition when it had been in a quarter of an hour. On returning at the end of an hour from the commencement of the experiment, I found the mouse lying still. It was taken out, and it moved spontaneously, endeavouring to walk, but falling over; it was quite sensible to being pinched. In five minutes it had recovered power to walk, but was not yet conscious of danger, as it would have walked off the table if not prevented. In a few minutes longer it had recovered its usual state.

Exp. 30.-- Another mouse was placed in the same jar with eight grs. of nitric ether. It became affected in ten minutes, and at the end of a quarter of [1074/1075] an hour had ceased to move, but lay breathing naturally 160 times in the minute. It remained in this state till removed half an hour after the commencement of the experiment, when it was found to be relaxed, and totally insensible. It began to move in ten minutes; it could walk at the end of a quarter of an hour, and in a little time longer was quite active.

We perceive from the above experiments that half a grain of nitric ether to each 100 cubic inches of air suffices to induce the second degree of narcotism, and one grain the fourth degree. I have not met with a statement of the specific gravity of the vapour of this ether in any work to which I have referred, and consequently I endeavoured to determine it myself--not with great nicety, but with sufficient accuracy to satisfy the purpose of this inquiry. I made it to be 5.67; and half a grain of vapour in 100 cubic inches of air saturated with it at 100° is 15.7 cubic inches, and 0.284÷15.7 will give 0.018, or rather less than one fifty-fifth, as the relative saturation of the blood with nitric ether in the second degree of narcotism. One grain produces 0.568 of a cubic inch of vapour: and this, divided by 15.7, gives 0.0361, or very nearly one twenty-eighth, as the relative saturation of the blood in the fourth degree of narcotism. So we find that the quantity of the vapour in the blood, viewed in relation to what it would dissolve, is the same as in the cases of chloroform and sulphuric ether. In some experiments on birds, a rather larger quantity of vapour was required; but when their higher temperature was taken into account the relative proportion to what the air would take up was found to be the same, and, consequently, their blood was saturated to just the same extent.

One part by measure of nitric ether requires 52 parts of serum at 100° to dissolve it, and 52 x 56 = 2912; consequently, one part in 2912 is the proportion in the blood in the second degree of narcotism; and considering the average quantity of serum in the body, as before, to be 410 fluidounces, we get by calculation 67 minims as the whole quantity in the blood in this degree; and twice as much, or 2 drachms and 14 minims, in the fourth degree. These quantities agree with the little experience I have had of its effects on the human subject.

From its slight pungency, and the gradual way in which, owing to its sparing volatility, its effects are produced, nitric ether would be a very safe anaesthetic, suitable for minor surgical operations if its effects were agreeable, but such is apparently not always the case. M. Chambert met with vomiting in most of the dogs to which he gave it, and was deterred from inhaling it himself. Dr. Simpson states, in the Monthly Journal of April last, that he had found it to produce sensations of noise and fullness in the head before insensibility, and, usually, much headache and giddiness afterwards. I have inhaled a small quantity of it on two or three occasions, and it caused a disagreeable feeling of sickness each time. I have given it only to one patient, but in that instance it acted very favourably. A middle-aged man applied at St. George’s Hospital, on May 26, to have a tooth extracted. He inhaled from the apparatus I use for chloroform. Soon after he began his pulse became accelerated and increased in force, and his face rather flushed. He continued to inhale steadily for three minutes, when I found that the sensibility of the conjunctiva was considerably diminished, although voluntary motion continued in the eyes and eyelids, the expression of his countenance not being altered from that of complete consciousness and he held his head upright. The vapour was left off, and the tooth, which was firmly fixed, was taken out by Mr. Price, the dresser for the week, without any sign of the operation being felt; the man holding his mouth wide open in an accommodating manner. A minute afterwards he began to spit on the floor; and being questioned, he said that he had no knowledge of the removal of the tooth, and should have thought that he had never lost his senses, except for what he found had been done. His feelings were not unpleasant whilst inhaling, and he felt well, and walked away in a few minutes afterwards. A fluid-drachm and a half was employed, and it was not all used. There was perfect immunity from pain, whilst the narcotism of the nervous centres was not [1075/1076] carried further than the second degree: this, however, I do not look on as a peculiarity of nitric ether, for I have met with it occasionally from chloroform and sulphuric ether when the vapour was introduced slowly. The above case, I think, affords encouragement for further trials of this medicine.

Bisulphuret of Carbon.

This substance is well known to every one at all conversant with chemistry. It is a transparent colourless liquid, of sp. gr. 1.272, having a very fœtid odour, and boiling at about 113°. A paragraph copied from the Morgenblad went the round of the journals of this country about the end of February last, stating that M. Harald Thanlow, of Christiana, in Norway, had discovered a substitute for chloroform and ether, in a sulphate of carbon, a very cheap substance made from sulphur and charcoal. This, of course, could be nothing else than the bisulphuret of carbon. I immediately examined its effects of animals, and found that it causes convulsive tremors, but that the kind of narcotism such as ether produces may be recognized. On account of the great volatility and very sparing solubility of this substance, the point of relative saturation of the blood by it is soon reached.

The following experiments will shew both the action of the yapour [vapour] and the quantity of it in the blood.

Exp. 31. -- Two grains of bisulphuret of carbon were diffused through the air in a jar holding 200 cubic inches, and a white mouse was introduced. In three minutes it was altered in its manner, and no longer regarded the approach of the hand towards it. In six minutes tremors came on, which soon became violent, and lasted till after the mouse was taken out at the end of ten minutes; but voluntary motion continued along with the tremors. When taken out, it flinched on being pinched; attempted to walk, but fell over on its side: it had no appreciation of danger at first, but it quickly recovered.

Exp. 32. -- A common mouse was put into a jar holding 800 cubic inches, in which 12 grains of bisulphuret of carbon had been diffused, being a grain and a half to each 100 cubic inches. In a minute it began to have convulsive tremors whilst still walking. In half a minute more, voluntary motion ceased, but the tremors continued. It was removed at the end of ten minutes, was sensible to pricking and pinching, and in a minute or two began to recover voluntary motion, the trembling of the whole body continuing for a little time after it was able to walk.

Exp. 33. -- A white mouse was placed in the jar of 200 cubic inches capacity, with four grains of this substance in the form of vapour. It became quickly affected, and was lying powerless in less than half a minute. Convulsive tremors came on immediately after it fell, and lasted till death. At the end of four minutes the breathing became difficult, being performed only by distant convulsive efforts. The mouse was immediately removed, but only gave one or two gasps afterwards.

In another experiment, in which there were two and a quarter grains to each 100 cubic inches of air, the mouse, after running about for a minute, fell down, and stretched itself violently out, and died.

There is no stage of muscular relaxation prior to death by this vapour, as by those we have previously considered, when their effects are gradually induced; but tremulous convulsions of the whole body continue till death, which seems to be threatened almost as soon as complete insensibility to external impressions is established.

In Exp. 31, narcotism to the second degree was occasioned by one grain to 100 cubic inches. The sp. gr. of the vapour of bisulphuret of carbon being 2.668, it will be found that one grain of the liquid must produce 1.209 cubic inches of vapour; and I find that air, when saturated with it at 100°, expands to four times it former volume, so that 100 cubic inches contain 75 of vapour. Therefore 1.209 ÷ 75 gives 0.0161, or one part in 62 of what the blood would dissolve, as the relative saturation of the blood in the second degree of narcotism; and, as Exp. 33 may be regarded as the nearest approach to the fourth degree that we can get with this vapour, twice as much, or one part in 31, is the relative amount for that degree. These proportions do not differ much from those arrived at in the inquiries concerning the vapours previously examined.

Serum at 100° dissolves, as nearly as I can determine, just its own volume [1076/1077] of the vapour of bisulphuret of carbon; and, as the liquid is 408 times as heavy as its own vapour at the temperature of 100°, it will be found, by a similar calculation to that made with respect to the vapours treated of previously, that about 7½ minims is the average quantity that there should be in the whole blood of the human subject in the second degree, and 15 minims in the fourth degree of narcotism. When the great volatility of this substance is also taken into account, it will be perceived that its effects, when inhaled, must be most powerful. Indeed, I feel convinced, that, if a person were to draw a single deep inspiration of air saturated with its vapour at a summer temperature, instant death would be the result. Although its odour is offensive, it is not difficult to inhale; and Dr. Simpson has given it in a surgical operation and an obstetric case; he also informs us (op. cit.) that its effects were so powerful and so transient, that it was very unmanageable, and that it also cause some unpleasant symptoms, and he does not recommend its use.

Benzin or Benzole.

This substance was first discovered by Dr. Faraday, as a product of the distillation of compressed oil-gas, and named bicarburet of hydrogen; it was afterwards obtained by Mitscherlich, by distilling a mixture of benzoic acid and slaked lime; latterly Mr. Blatchford Mansfield has obtained it by the distillation of coal-tar. It consists of carbon and hydrogen, as its first name implied, the proportions being C12H6. It is a clear, colourless, and very mobile liquid, of sp. gr. 0.85, and having an aromatic odour. It has been described as boiling at 180°; and a portion with which Mr. Mansfield favoured me, boils, as he always found it to do, about 178°. There is no difference either in sensible properties or physiological effects between the benzin made from benzoic acid, and that obtained from coal-tar. Like the substance last treated of, it causes convulsive tremors in addition to the other symptoms of narcotism; they usually begin in animals before voluntary motion ceases, and continue as long as the vapour is applied, and during part of the recovery, and until death when animals are killed by it. The tremors are usually violent, affecting the whole body, and accompanied in birds with flapping of the wings.

One experiment will suffice to show the effects of this vapour.

Exp. 34. -- Six grains of benzin were diffused through the air in a jar holding 800 cubic inches, being three-quarters of a grain for each 100 cubic inches; and a half-grown white mouse was introduced. In less than a minute it began to shake and tremble, and ceased to move voluntarily, but every now and then gave a sudden start; this start could also be occasioned at any time by striking the jar so as to make a noise. This mouse continued in the same state till removed at the end of a quarter of an hour; it was totally insensible to pricking and pinching, which produced not the slightest effect on it, whilst at the same time a sharp noise near it cause it to start. Five minutes after its removal it began to recover voluntary motion, but the tremors continued a little longer. The mouse was soon as well as before the experiment. Less than half a grain of benzin to each 100 cubic inches of air, suffices to impair the voluntary motion, and alter the manner of an animal; rather more than half a grain causes convulsive tremors, and three-quarters of a grain and upwards produces complete insensibility, whilst two grains will take away life. In the experiment related above, the fourth degree of narcotism appeared to be induced by three-quarters of a grain, but one grain to the 100 cubic inches of air is the average quantity for that state in several experiments. The specific gravity of the vapour of benzin being 2.738, one grain of the liquid makes 1.179 cubic inch of vapour; and I find that air saturated with it at 100°, contains 20 per cent of it by measure: so 1.179 ÷ 20 will give the relative saturation of the blood. It is 0.058, or one-seventeenth part of what it would dissolve. This is a greater proportion than we arrived at in examining the vapours treated of above.

Benzin requires 270 parts of serum for its solution; consequently, by the kind of calculation made before, 42 minims is obtained as the average quantity that there would be in the human body, if narcotism were [1077/1078] carried to the fourth degree by this vapour. It follows from this that benzin must be powerful in its effects, and such I have found to be the case, but they are not so rapidly produced as the effects of chloroform, on account of its lesser volatility. I employed it in some cases of tooth-drawing, and in one amputation, in St. George’s Hospital, at the latter part of last year. Its action in the minor operations was very nearly the same as that of nitric ether, in the case related above; but in the amputation, where its effects were carried further, the patient had violent convulsive tremors for about a minute, which, although not followed by any ill consequences, were sufficiently disagreeable to deter me from using it again, or recommending it in the larger operations.

(To be continued.)

Return to John Snow Publications

Return to John Snow Publications

35. On narcotism by the inhalation of vapors. (part 4)

35. On narcotism by the inhalation of vapors. (part 4)

Source: Snow, John. London Med. Gazette 42, 25 August 1848, pp. 330-35 (part 4).

By John Snow, M.D.

Vice-President of the Westminster Medical Society.

[Part 4]

On bromoform, bromide of ethyle, and Dutch liquid--General results of the experiments--The strength of narcotic vapours in the inverse ratio of their solubility in the blood.

Description of the physiological effects of chloroform.

Bromoform.

This is a volatile liquid of the same composition as chloroform, except that three atoms of bromine occupy the place of the same proportion of chlorine. It is made in the same way as chloroform, bromide of lime being used instead of chloride. I have repeatedly made it, but have never succeeded in obtaining more than a few grains in a purified state, although I used an ounce of bromine in making the bromide of lime on each occasion; consequently it is very expensive. It is extremely fragrant, having an odour that is, in my opinion, much pleasanter than that of chloroform or any other of this class of substances with which I am acquainted. It boils at about 184° Fah.; but, as its vapour is twice as heavy as that of chloroform, it is in point of fact nearly as volatile as that liquid. It is very pleasant to inhale, but I have never breathed in more than a few grains at a time, and, therefore, cannot speak of its operation on the human subject. Its effects on animals closely resembles those of chloroform.

The two following experiments will serve to illustrate the action of bromoform, and to determine the quantity in the blood. --

Exp. 35. -- A common mouse was placed in a jar containing 400 cubic inches, in which three grains of bromoform had been diffused. In the course of four or five minutes it became unsteady in its walking, and ceased to regard objects in its way. It did not get further affected, except to become rather sluggish, and, when removed at the end of twenty minutes, was capable of voluntary motion. It did not regard a slight pinch, but flinched when the soft part of its foot was pinched severely. It recovered gradually and was pretty well re-established in half an hour.

Exp. 36. -- Another mouse was placed in the same jar with six grains of bromoform: it was more quickly affected, and, at the end of five minutes, all voluntary motion had ceased, and it lay breathing naturally and rather deeply. It was removed at the end of a quarter of an hour, and did not stir on being pinched. It began to recover voluntary motion in ten minutes, but staggered at first. In a little more than half an hour it had recovered.

In the first of these experiments the second degree of narcotism was caused by three-quarters of a grain of bromoform to each 100 cubic inches of air. The specific gravity of the vapour of bromoform is stated, in Thompson’s Chemistry of Organic Bodies, to be 8.785 which gives 0.275 of a cubic inch as the quantity of vapour that three-quarters of a grain would yield; and I find that fifteen cubic inches of this vapour are contained in 100 of air saturated with it at the temperature of 100°; consequently the air of the jar contained 0.275 ÷ 15 = [0].00183, or nearly one fifty-fourth part of what it would take up if saturated at 100°, and according to the principles explained in a former part of these papers,* (* Vol. xli. p. 850 [first page of Part 1]) the blood of the mouse would contain just the same proportion--one fifty-fourth of what it could dissolve. In the other experiment, the fourth degree of narcotism was produced by twice the quantity--a grain and a half to each 100 cubic inches, which, by the same computation, gives about one twenty-seventh part of what the blood would take up. These proportions are nearly the same as in the case of most of the substances previously examined. I have not ascertained the exact solubility of bromoform, and consequently cannot compute the absolute quantity in the blood, but it resembles chloroform in being very sparingly soluble.

I have not heard that any one else has examined the effects of the vapour of bromoform; but Dr. Glover mentions an experiment in his valuable paper "On Bromine and its Compounds,"* (*Edin. Med. and Surg. Jour., Oct. 1842) in which bromoform in the liquid state was introduced into the stomach of a rabbit, with the same results as in other experiments with similar bodies: these were death, with congestion of the lungs and stomach.

Bromide of Ethyle.

Bromide of ethyle, or hydrobromic ether, is a very volatile liquid, boiling, as I have found, at 104°. It has a pleasant but somewhat pungent taste and smell. It was discovered by Seru[l]las in 1827, and is formed by the action of phosphorous on a solution of bromine in alcohol. I am not aware that its physiological effects have been examined except in a few experiments which I have performed with its vapour. I will cite two of them to illustrate its effects. The bromide of ethyle was made by myself.

Exp. 37. -- Eight grains of bromide of ethyle were introduced into a jar containing 400 cubic inches, and the vapour which instantly resulted was equally diffused by moving the jar. A mouse was then put in. In about four minutes it began to stagger and fall over, and was quite regardless of external objects. It did not get affected beyond this extent, except that it became rather feeble. It was taken out at the end of a quarter of an hour, having the power of voluntary motion, but rolling over in its attempts to walk. It flinched with severe, but not with slight pinching. In ten minutes it had pretty well recovered.

Exp. 38.--Another mouse was placed in the same jar with sixteen grains of bromide of ethyle. In two minutes it had ceased to move, not having shewn any signs of excitement. It lay motionless, breathing at first deeply, afterwards more naturally. It was removed at the end of a quarter of an hour, and was found to be totally insensible. In five minutes it began to move, but rolled over in its first attempts to walk. Twenty minutes after its removal, it appeared to have recovered from the effects of the vapour.

Connected with the great volatility of this liquid is the increased quantity of it required to be present in the air to produce a given effect,--in accordance with the law which requires that the blood must be impregnated to a certain extent relatively to what it could imbibe. In one experiment I performed with this substance, one grain to each 100 cubic inches of air produced no appreciable effect whatever on a mouse confined for twenty minutes in it, although with that quantity of several less volatile bodies complete insensibility would have been induced.

In experiment 37 two grains to each 100 cubic inches of air produced the second degree of narcotism; and in the following experiment four grains produced the fourth degree. The specific gravity of the vapour of bromide of ethyle is, I find 3.78, the atom being represented by two volumes. Two grains will consequently occupy 1.706 cubic inches in the form of vapour. At the temperature of 100° the vapour of bromide of ethyle almost excludes the air, and occupies 92.8 per cent of its place. So 1.706 ÷ 92.8 gives 0.0183, or nearly one fifty-fourth, as the relative saturation of the blood with this vapour for the second degree of narcotism; and there would be twice as much, or one twenty-seventh, for the fourth degree.

I have not ascertained by direct experiment how much bromide of ethyle serum will dissolve, but I find that water dissolves about one-sixtieth of its volume of it; and as the solubility of liquids of this kind is nearly the same in water as in serum, this may safely be taken as the standard;--when, if we consider the average quantity of serum in the human body to be 410 fluid ounces, as in a former part of these papers, and make the kind of calculation there made, we shall find that one fluid drachm and ten minims is the average quantity that there would be in the blood of a human subject in the second degree of narcotism; and two drachms and twenty minims in the fourth degree.

Dutch Liquid.

In recent works on chemistry this substance is called the hydrochlorate of chloride of acetyle. It is formed by the combination of equal volumes of olefiant gas and chlorine. It has a taste at once sweet and hot, and a pungent ethereal odour. It boils at 180°, [331/332] and not at 148°, as Dr. Simpson states in some brief remarks on it in the Edinburgh Monthly Journal for April last, where he informs us that its vapour, when inhaled causes so great irritation of the throat that few persons can persevere in inhaling it long enough to produce anesthesia; but that he had, however, “seen it inhaled perseveringly until this state, with all its usual phenomena, followed; and without excitement of the pulse or subsequent headache.” My experiments with it have been confined to animals; and the two following will serve as a sample of them: --

Exp. 39. -- One grain and a half of Dutch liquid was diffused through the air of a jar containing 400 cubic inches, and a mouse was introduced. After ten minutes had elapsed it began to stagger in its walk, and it continued to do so till it was removed at the end of half an hour. It was occasionally lying still, but always began to walk in an unsteady manner when the jar was move. It was sensible to pinching on its removal, and in a quarter of an hour had recovered from its inebriation. It continued well.

Exp.40. -- A mouse was put into the same jar after three grains of Dutch liquid had been diffused in it. It began to stagger sooner than that employed in the last experiment; and at the end of ten minutes had ceased to move, without having had any struggling or rigidity; and it was not disturbed on the jar being moved. It lay breathing naturally till it was taken out at the end of half an hour, when it was found to be totally insensible to pinching. In ten minutes after its removal it began to move, but rolled over in its efforts to walk; when half an hour had elapsed it appeared to have recovered entirely form the narcotism, but was less lively than before; and two or three hours afterwards it was observed to be suffering with difficulty of breathing, and it died in the course of the day. The lungs were congested and of a deep vermilion colour, probably the result of inflammation, occasioned by the irritating nature of the vapour. The right cavities of the heart were distended with dark-coloured coagulated blood. The same appearances were met with in another mouse that died in the same way after breathing this vapour.

In the first of these two experiments the second degree of narcotism was effected by three-eights of a grain of vapour to each 100 cubic inches of air; and as the specific gravity of this vapour is 3.4484, three-eights of a grain must occupy 0.35 of a cubic inch. I find that air, when saturated with vapour of Dutch liquid at 100°, contains 17.5 per cent., and therefore 0.35 ÷ 17.5 gives 0.02, or one-fiftieth, as the relative saturation of the blood in this degree. In the other experiment the fourth degree of narcotism was caused by twice as much vapour, or three-quarters of a grain to each 100 cubic inches, and, consequently, the blood would contain twice as much, or one twenty-fifth part of what it would hold in solution if saturated. I have ascertained that Dutch liquid requires about 100 parts of water for its solution, and taking its solubility in the serum to be the same, the blood would contain one part in 5000 in the second, and one part in 2500 in the fourth degree of narcotism, which in the human subject would be, on an average, 46 minims and 92 minims respectively.

General results of the experiments.

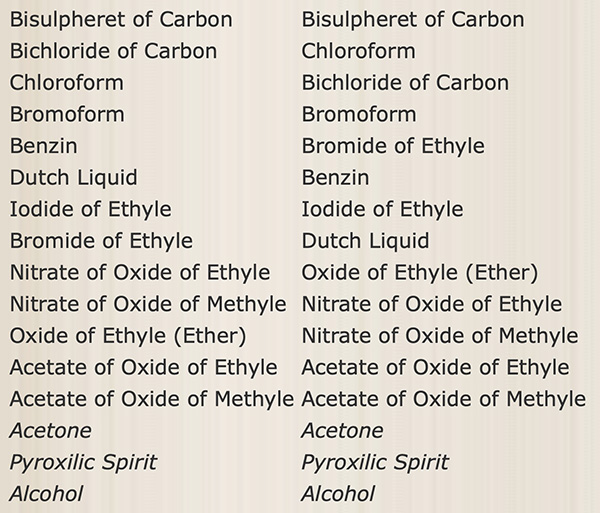

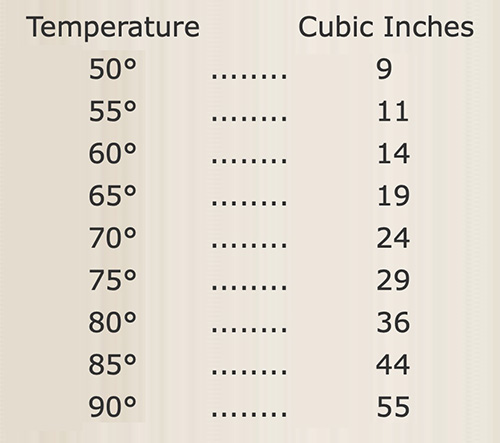

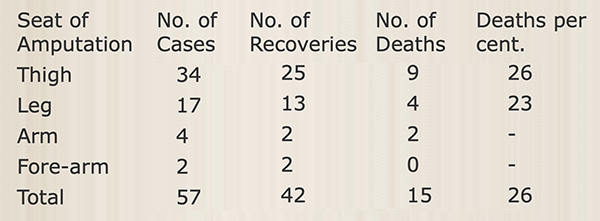

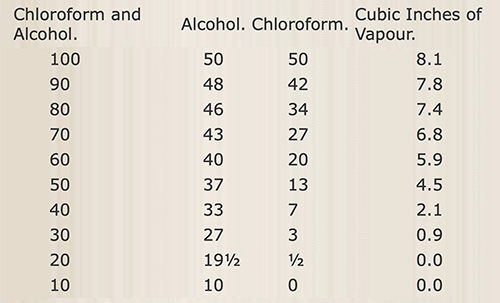

We have now seen the result of this experimental inquiry into the action of eight volatile substances, viz.: chloroform, ether, nitrite of oxide of ethyle, bisulphuret of carbon, benzin, bromoform, bromide of ethyle, and Dutch liquid. We find that the quantity of each substance in the blood, in corresponding degrees of narcotism, bears a certain proportion to what the blood would dissolve-–a proportion that is almost exactly the same for all of them, with a slight exception in the case of benzin, which I believe is more apparent than real. The actual quantity of the different substances in the blood, however, differs widely; being influenced by their solubility. When the amount of saturation of the blood is the same, then it follows that the quantity of vapour required to produce the effect must increase with the solubility, and the effect produced by a given quantity must be in the inverse ratio of the solubility, as I announced some time ago.* (*Medical Gazette, March 31.) This rule holds good with respect to all the substances of this kind that I have examined; including, in addition to those enumerated in this paper, bichloride of carbon, iodide of ethyle, acetate of oxide of ethyle, nitrate of oxide of methyle, acetate of oxide of methyle, pyroxilic spirit, acetone, and alcohol. The exact proportion in the blood, in the case of the three last mentioned [italicized in the table below], cannot be ascertained directly by experiments of the kind detailed above; for, being soluble to an unlimited extent, they continue to be absorbed as long as the experiment lasts: but from the large quantity of these substances that is required to produce insensibility, they confirm the rule stated above in a remarkable manner.

This general law, of course, does not apply to all narcotics; not, for instance, to hydrocyanic acid, but only to those producing effects analogous to what are produced by ether, and having, I presume, a similar mode of action. I am not able at present to define them better than by calling them, that group of narcotics whose strength is inversely as their solubility in water (and consequently in the blood). In estimating their strength, when inhaled in the ordinary way, another element has to be taken into the account, viz., their volatility; for that influences the quantity that would be inhaled. By multiplying together the number of parts of water that each substance requires for its solution, and the number of minims of each substance that air will hold in solution at 60°, we get a set of figures expressive of the relative strength of each, when breathed in the ordinary way; and by another method of calculation the time might be expressed, in minutes and seconds, that it would take, on an average, to render persons, breathing in the usual way, insensible by each substance: but I shall here confine myself to enumerating the bodies I have examined in two columns; arranging them, in the first column, in the inverse order of their solubility, which is the direct order of their actual potency; and in the second column, in the order in which they stand after their volatility is taken into the account, which is the order of their potency when mixed with air till it is saturated at any constant temperature.

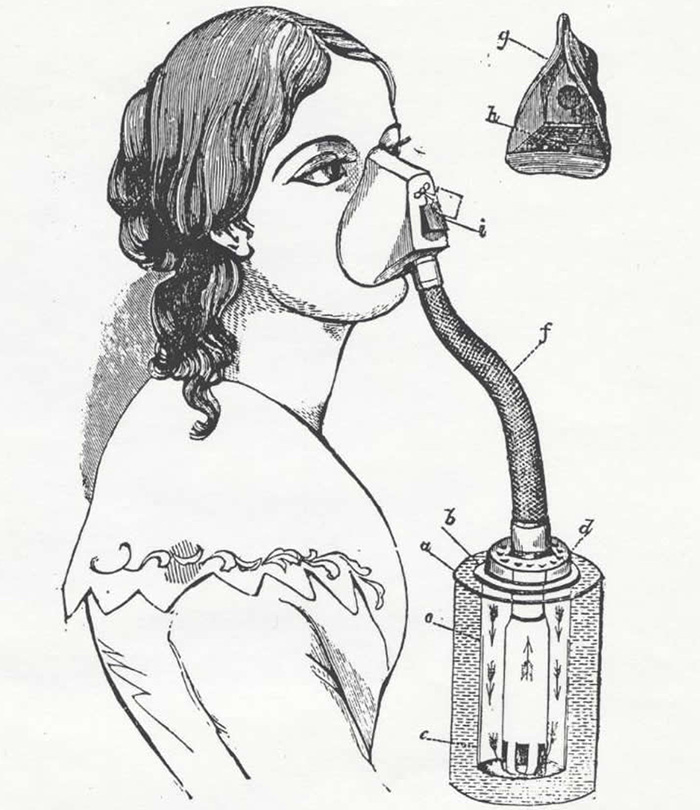

The general law, stated above, respecting the solubility of these liquids in the blood, applies also, with certain modifications, to a number of bodies which are gaseous at ordinary temperatures, and there are several important conclusions to be deduced from it. But before proceeding further in the attempt to give a general history of narcotic vapours and gases, and to determine what substances should be included in the list or otherwise, it will be well for me to describe, more particularly than I have done, the nature of the narcotism produced by the class of bodies we are considering, of which chloroform may be properly be taken as the type. I shall, therefore, next proceed to give the best description that I can of the effects of chloroform, having especially in view the practical importance of the agent; and shall make all the remarks that I am able to include in a brief space, on the administration of chloroform in surgical operations, medicine, and midwifery.

Description of the effects of Chloroform.

I may premise, that in applying the term narcotic to chloroform and other volatile substances, I employ it in the extended sense in which it is used by writers on materia medica and toxicology, who make it include all the substances which act on the nervous system; and I apply the term narcotism to designate all the effects of a narcotic, as I am entitled to do by strict etymology, and do not confine it, as the practice has generally been, to express a state of complete insensibility. I do not object to the term anesthetic, but I use that of narcotic as being more comprehensive, and including the other properties of these vapours as well as that of annulling common sensibility.

To facilitate the description, I divide all the effects of chloroform short of the abolition of life, into five degrees. I use the term degree in preference to stage, as, in administering chloroform, the slighter degrees of narcotism occur in the latter stages of the process, during the recovery of the patient, as well as in the beginning.

The division into degrees is made according to symptoms, which, I believe, depend entirely on the state of the nervous centres, and not according to the amount of anæsthesia, which I shall give good reason for believing depends very much on local narcotism of the nerves.

In the first degree I include any effects of chloroform that exist while the patient possesses perfect consciousness of where he is, and what is occurring around him. As the sensations caused by inhaling a small quantity of chloroform have been experienced by nearly every medical man in his own person, I need not attempt to describe them. They differ somewhat with the individual, but may be designated as a kind of inebriation, which is usually agreeable when induced for curiosity, but is often otherwise, when the patient is about to undergo an operation: in such cases, however, this stage is very transitory. Although it is the property of narcotic vapours to suspend the functions of different parts of the nervous system in succession, yet they probably influence every part of that system from the first, but in different degrees.

I have found that my vision became impaired when inhaling chloroform, whilst I should have thought it as good as ever, had it not been that the seconds pointer disappeared from the watch on the table before me; and I could only discover it again by stooping to within a few inches within it. Common sensibility becomes also impaired, so that the pain of disease, which is generally due to a morbid increase of the common sensibility, is in many cases removed, or relieved, according to its intensity. And hence it is that patients are able to inhale chloroform and ether, without assistance, for the relief of neuralgia, dysmenorrhœa, and other painful affections; the latter, which acts less rapidly, being the best adapted for this kind of domestic use -- chloroform being perhaps not perfectly safe. The sufferings attendant on parturition, when not unusually severe, may generally be prevented, as stated by Dr. Murphy* (* Pamphlet on chloroform in the practice of midwifery.), without removing the patient’s consciousness; but I have met with no instance in which the more severe kind of pain caused by the knife was prevented, whilst complete consciousness existed, except in a few cases, for a short time, as the patients were recovering from the effects of the vapour, having just before been unconscious.

In the second degree of narcotism, there is no longer correct consciousness. The mental functions are impaired, but not altogether suspended. Generally, indeed, the patient neither speaks nor moves, but it is possible for him to do both; and this degree may be considered to be analogous to delirium, and to certain states of the patient in hysteria and concussion of the brain; and it corresponds with that condition of an inebriated person, who is not dead drunk, but in the state described by the law as drunk and incapable. It is so transitory, however, that the patient emerges to consciousness in a very few minutes at the farthest, if the chloroform is discontinued. This degree, any more than the others, cannot properly be compared to natural sleep, for the patient cannot be roused at any moment to his usual state of mind. Persons sometimes remember what occurs whilst they are in this state, but generally they do not. Any dreams that the patient has, occur whilst he is in this degree, or just going into, or emerging from it, as I have satisfied myself by comparing the expressions of patients with what they have related afterwards. There is generally a considerable amount of anæsthesia connected with [334/335] this degree of narcotism, and I believe that it is scarcely every necessary to proceed beyond it in obstetric practice, not even in artificial delivery, unless for the purpose of arresting powerful uterine action, in order to facilitate turning the fœtus. For, on the one hand, obstetric operations are less painful than those in which the knife is used, and, on the other, it is not so necessary that the patient should be perfectly motionless during their performance, as when the surgeon is cutting in the immediate vicinity of vital parts.* (*Mr. Gream and Dr. Wm. Merriman, who have done me the honour of quoting from my essays on ether and chloroform, in their pamphlets, have applied to midwifery, what I meant to apply only to delicate and serious surgical operations, and have grounded objections on the supposed necessity of producing a deep state of narcotism.) There is sometimes a considerable amount of mental excitement in this degree, rendering the patient rather unruly; but a further dose of the vapour removes this by inducing the next degree of narcotism, and there is less difficulty from this source with chloroform than with ether, since its action is more rapid, and two or three inspirations often suffice to overcome the excitement. Very often, however, the patient is quiet, and to a certain extent tractable in this degree, and if sufficient anæsthesia can be obtained, there are certain advantages in avoiding to carry the narcotism beyond it for minor operations, especially tooth-drawing, as I shall explain when I enter on the uses and mode of applying chloroform, at the end of this sketch of its physiological effects. The patient is generally in this degree during the greater part of the time occupied in protracted operations; for, although, in most cases, it is necessary, as I have formerly stated, to induce a further amount of narcotism before the operation is commenced, it is not usually necessary to maintain it at a point beyond this.

(To be continued.)

Return to John Snow Publications

Return to John Snow Publications

36. "On narcotism by the inhalation of vapors." (part 5)

36. "On narcotism by the inhalation of vapors." (part 5)

Source: Snow, John. London Med. Gazette 42, 8 September 1848, pp. 412-16 (part 5).

By John Snow, M.D.

Vice-President of the Westminster Medical Society.

[Part 5]

Description of the physiological effects of chloroform, continued--when inhaled it acts on the nerves as well as on the nervous centres. Phenomena attending death from chloroform--its action on the heart of the frog.

The advent of the third degree of narcotism is marked by cessation of all voluntary motion. Usually the eyes become inclined upwards at the same time; and there is often a contracted state of the voluntary muscles, giving rise to more or less rigidity of the limbs. This contraction is greater and more frequent from chloroform than from ether, and, by affecting the muscles of the jaw, it sometimes causes a considerable obstacle to operations on the mouth. As there are no signs of ideas in this degree, I believe that there are none, and that the mental faculties are completely suspended: consequently the patient is perfectly secured against mental suffering from any thing that may be done. It does not follow, however, that an operation may always be commenced immediately the narcotism reaches this degree, for anæsthesia is not a necessary part of it; and unless the sensibility of the part to be operated on be suspended, or very much obscured, there may be involuntary movements sufficient to interfere with a delicate operation--not merely reflex movements, but also coordinate actions, such as animals may perform after the cerebral hemispheres are removed, the medulla oblongata being left. Under these circumstances an operation usually causes a contraction of the features expressive of pain, and sometimes moaning or cries, but not of an articulate kind. Whether or not these signs are to be considered proofs of pain, will depend on the definition given to the word; and if they do not interfere with the operator, or influence the recovery, they can be of no consequence as there is no pain which has an existence for the patient. To obtain anæsthesia when it does not exist in this degree, and thus to prevent these symptoms if we desire, it is not necessary to carry the narcotism further, but only to wait at this point a few moments, giving a little chloroform occasionally to prevent recovery, and allow time for it to permeate the coats of the small vessels, and act more effectually on the nerves. The sensibility of the conjunctiva is a correct index of the general sensibility of the body; and until it is either removed or very much diminished, an operation of delicacy cannot be comfortably performed. Accordingly, in administering chloroform, as soon as the patient has inhaled sufficient to suspend voluntary motion, I raise the eyelid gently, touching its free border. If no winking is occasioned the operation may begin in any case, but if it is I wait a little time, till the eyelids either become quite passive or move less briskly. The state of the eye itself is observed, by this means, at the same time. It is usually turned up, and the pupil contracted, as Mr. Sibson has stated,* in the condition which I term the third degree of narcotism. (*Med. Gaz., Feb. 18. I think that the turning up of the eyes is not so constant as Mr. Sibson believes, as I have been unable to observe it in some patients at any stage.) The vessels of the conjunctiva, also, are sometimes injected, but more frequently they are not.